From The Kathmandu Post (31 July, 2015)

The ills of governance result from the unaccountability in our electoral politics

Where else would you go westward 160 km on a winding hill highway in order to travel east, for four decades on end, and never think of the costs and consequences? Nepal, of course. This derives from the odd and unique mixture of unrepresentative politics, unaccountable civil society, all-permeating corruption and onerous geopolitics that result in the curse that can be termed ‘rule by syndicate’.

The ridgeline-following Tribhuvan Highway (byroad ko baato) was completed in 1956 with Indian assistance, and the Chinese built the river-valley-hugging Kathmandu-Pokhara Prithvi Highway, connecting the midpoint of Mugling to Narayanghat in 1973. Narayanghat had already been linked to Hetauda by the Americans a decade previously, and from there onward the East West Highway divided up in construction between the Russians, Indians and British.

The bulk of the passenger and goods traffic into Kathmandu has always come from the east, and the passenger traffic too heads back that way. A direct road from Hetauda longitudinally up the Bagmati Valley to Kathmandu, more or less the line being followed by the ‘fast track’ in the making, for a fully-loaded truck or bus, would take less than two hours. Instead, for four decades, we have traversed 77 km west from Hetauda to Narayanghat and the 160 km north-east-east to Kathmandu.

It boggles the mind, the millions of human-hours wasted over the decades in this mad detour, as also the calculation of the extra billions spent in the cost of fuel, tyres, bus bodies and insurance, not to mention the overall burden on the economy and environment. Even more challenging than this fairly straightforward accounting of the economic, social and environmental costs is to attempt to understand why we have allowed it, till the present.

Even today, the bulk of the traffic from Kathmandu to the eastern Tarai-Madhes goes via Narayanghat. The just inaugurated BP Highway to Sindhuli cannot take heavy vehicles, the ‘Sumo Rajmarg’ to Bhimphedi can take only that—Tata Sumo jeeps. The 42-km long Hetauda-to-Kathmandu goods ropeway was probably the finest thing thought of in modern Nepali transport, built by the Americans in 1964. It was allowed to die in the early 1990s, and the forlorn gondolas still ride the cables that straddle the mountaintops high above Sumo Rajmarg.

In the meantime, we have unplanned rural roads wreaking environmental and cultural mayhem all over, with alignments laid out by excavator operators; attempts at a railway alignment that would cut the Chitwan National Park into half; and utter neglect of the Hulaki Rajmarg, so vital to inject economic energy into the southern reaches of Tarai-Madhes.

Tribhuvan International

Before delving into why things are so cocked up in our dear Nepal, let us lift up one more specimen for scrutiny, and it will be the venerable Tribhuvan International Airport (TIA), it of the water-less toilets, landscape-deadening billboards, sinuous immigration lines and broken-down baggage carousels. Thank heavens for the designers and builders who put up such a fine architectural period piece of exposed brick against the side of the Gauchar plateau, which has stood the test of more than three decades of abysmal management, with even the signage, wall hangings, woodwork and marble flooring intact.

But everything else sucks, if you will excuse the intemperate language, which should be understandable under the circumstances. The airport could construct an entire reservoir from water harvesting to keep its toilets continuously washed, but will not do it. The new extensions have unsightly corrugated roofs in blue, just what you want to greet the visiting tourist with.

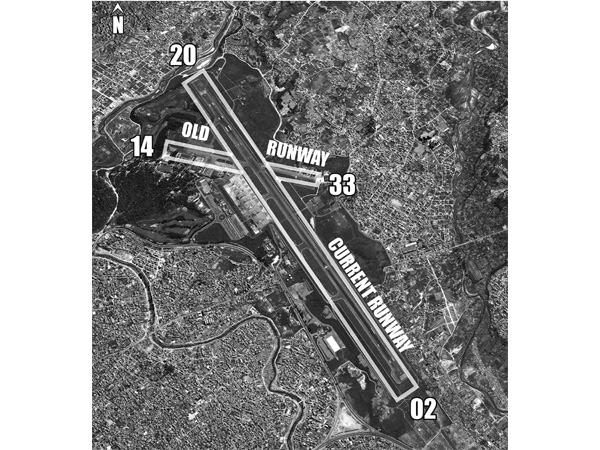

The air traffic has become unmanageable on the only runway (designation ‘02-20’) TIA has. One could have used the old runway ‘14-33’ by clearing the domestic parking and shifting the newly built Buddha Air hangar —this way the short-take-off-and-landing aircraft could land on the shorter old runaway, while expediting the arrivals and departures of international flights. But this would perhaps be too innovative and logical for our politicians and bureaucrats, and would not include lucrative building contracts.

Also, the 02-20 runway cannot handle many flights for the lack of another simple, do-able solution. On both the north and south ends, passenger jets have to enter the runway and roll all the way to the end before turning around to start the take off run, all of which takes time. In the meantime, planes stack up above Simara and Birgunj, in rare cases even half a dozen at a time.

The easy fix is to extend the taxiways all the way to the two ends, allowing aircraft to start their takeoff run as soon as they enter the active runway. This would cost no more than a few crores and the work is well within indigenous expertise. But we are programmed to wait for a ‘project’ funded by a multilateral bank, even as year after year TIA gets further demerits for one of the most inhospitable places in the world for airlines and passengers alike.

Politicians’ politics

If one looks hard enough, one can of course find glimmers of hope amidst the continuous disaster that is Nepal’s state administration – the relentless attempt at Bagmati cleanup by Chief Secretary Lila Mani Poudel who retires next week; the surprising success at halting the rapacious mining of Chure boulders for export to Bihar/Uttar Pradesh; the Chitwan National Park’s valiant efforts to prevent Kamalnayanacharya’s landgrab; and General Administration Minister Lal Babu Pandit’s multi-pronged campaign to halt ‘manparitantra’ in the bureaucracy.

Elsewhere, sadly, it is nothing but doom and gloom on the interface of politics and state administration, exemplified by the two examples I have chosen to present—the going-east-to-travel-west fiasco and the inability to extend two taxiways at TIA. There are a hundred thousand other things that are wrong with state administration and governance, starting with the tragically ponderous response to the April earthquakes, with no sense of urgency at all in appointing a CEO at the Reconstruction Authority.

Rather than simply bemoan our fate, one would have to try and understand the reasons for the errors in governance that have squeezed life out of our polity and economy. And at the centre lies the fulltime career track of our political leaders, which makes them cling to positions of power without the confidence of surviving otherwise, to circle the wagons in a cabal that does not do good nor allows others to.

This lack of career options makes the politicians corrupt and power-centered, unmindful of how they are perceived, and unwilling to learn anything other than the tricks to remain afloat politically. For these reasons, as was most evident in the earthquake aftermath, the topmost leaders have not spent time developing their understanding of Nepal’s physical geography and demographic diversity, which would allow them also to see the geophysical and societal potential of the naton-state.

The weakening of the state through 10 years of conflict, and the nearly a decade’s transition since, has of course played its role in weakening the politicians’ politics. The history of grovelling that marked the Panchayat era, the continuous weakening of our education system and the absence of social sciences learning, the conversion of our civil society from watchdog to a collection of funded yes-people, and so many other factors have resulted in the political parties’ seniormost coming to believe that they were born to rule serially, with the legislature and Constituent Assembly no more than an appendages.

And so, we have a revolving door at the prime ministerial office, and you ensure your turn by preventing healthy conduct of politics, starting with blocking representative governance at the local level through elections. The Panchayat system was rule-by-syndicate, with power concentrated within Narayanhiti. We now have syndicate politics in multiparty democracy with all the associated ills of mal-governance, corruption, lack of the confident spirit that comes from representation, and servility before foreign diktat.

We do seem to need a new set of leaders in the political realm, but all the talk of ‘youth leaders’ coming to the fore, it seems, will only bring another cabal to the top. One more reason for a new constitution, therefore, so that we may be able to start afresh, but the problem is that the constitution too is being prepared by a syndicate.

Hetterika! Is the appropriate response at this point, indicating frustration but a willingness to fight on regardless.