From The Kathmandu Post (14 August, 2015)

The primary concern with the proposed band-aid federalism is how it will hurt the poor of the Tarai-Madhes

Unexpectedly, the flashpoint of the federal agenda appeared not in the hotbed of identity-related tension elsewhere in the hills and the plains, but in the mid-western region which has been relatively aloof from the charged debates that have buffeted our two constituent assemblies.

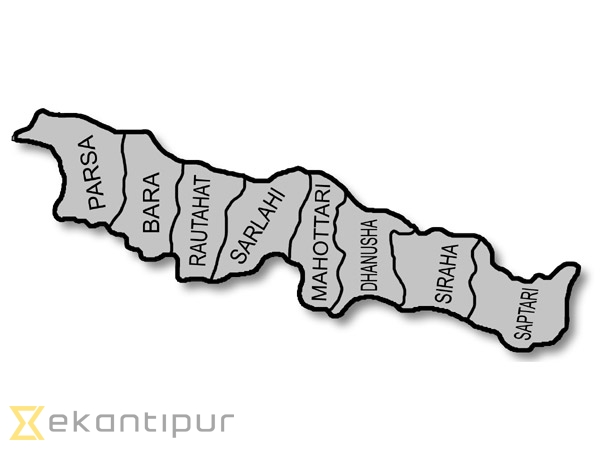

Amidst the push and pull of constitutional politics, the ethnic group that has been left most vulnerable is the Tharu of the plains, which is about as ‘indigenous’ as anyone can be in this country. By volume and depth of poverty, however, those who are most likely to be further impoverished by the federal formula are the inhabitants of the eight districts in the proposed Province 2.

Ironically, the most proactive and politicised effort on federal delineation during the second Constituent Assembly has been led by activists from this very region. There may yet be time for them to consider how the passionate demand for a total physical delinking of the plains from mid-hills might deliver an economically feeble province, incidentally with the highest density of population among the six proposed.

Provincialism and federalism

Provincialism in Nepal goes back to the time of the unifying king Prithvi Narayan, who devised stratagems to keep the subjugated principalities together. The Rana oligarchy created units for administrative control, and not much changed in the modern era despite the creation of zones, districts and development regions, with only the Local Self-Government Act trying to genuinely devolve power to the people.

Decentralisation came too late, given the rise of political awareness after the 1990 opening, even as a limited number of clans and communities continued their hold on the state machinery. Even so, the federal agenda was joined to the constitution-writing not by People’s Movement of 2006 but the Madhes Movement of a year later. The latter challenged the Kathmandu establishment on the two counts of historical marginalisation and ownership of state identity.

Federalism was embraced by the ethnicities and Madhesi citizens as the vehicle through which to upturn the iniquitous centralised state run by the Bahun-Thakuri/Chhetri-Newar nobility. They were resisted initially by those who insisted that society would do better by building on the success of decentralisation after 1990.

The notion of Nepal as a federal nation-state having been accepted, the Maoist party moved quickly to foist ethnic federalism, which in its early avatar included prior rights (agradhikaar) for selected ethnic groups in a country unique for its mixed habitation. Meanwhile, the plains’ politicos and activists came up with the ek-madhes-ek-pradesh proposal, a single plains province 500 miles long and 20 miles wide.

Even though the plains-only agenda was expanded to concede two provinces by the time of the second CA, it ignored all kinds of demographic issues on the ground. These included the class-and-caste differentiations within ‘core Madhes’, the language spectrum from Awadhi to Maithili, the place of the Muslims, Tharus and other smaller ethnicities, separate issues of Tarai and inner-Tarai, and the sizeable number of pahadiyas living in the flats. Most importantly, the formula overlooked economics and equity.

Powered as it was by the reality of historical exclusion, the federalism agenda held despite initial resistance within the political class. But the debate took an unhealthy turn as the populist blunderbuss was turned on all but those who supported identity-based federalism.

Band-aid exercise

Overall, the constitutional draft emerged as a sub-optimal hodgepodge because of the failure of civil society and academia to engage in the discussion on the basis of social science and constitutionalism. The constitution-writing was hijacked from the Assembly floor by a cabal of political leaders.

With the discussion happening behind closed doors, it became possible for embassies and ‘agencies’ to have inordinate influence on the federalism definition. Meanwhile, outside the Assembly, much of the debate was diverted by careerists funded by the unaccountable among donor organisations. As we all hopefully know by now, while genuine activists tend to lean towards give-and-take with the powers that be, the salaried careerists will proceed on the basis of dangerous all-or-nothing brinkmanship.

The performance of the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML in the second CA elections of November 2013, and the failure of the Maoists and Madhes-centric parties, was the voting public’s way of expressing its preference for the kind of federalism that supported socio-economic advancement. But the second CA was not allowed to have transparent debates on federalism, which would have tempered the acrimony that swirled around the demarcation exercise.

Identity vs. mixed-region

Within the establishment, the work on demarcation was monopolised by a few individuals with also an eye on personal constituencies and support bases. Outside the establishment, over the course of the second CA, while the demand for a single plains province more or less lapsed, the insistence on plains-specific demarcation remained strong.

The way the identity-based federalism activists posited the debate, it was one between the anti-federalists and pro-federalists. Whereas the dynamic difference was really between those who insisted on identity-based (including plains-specific) provinces and those who preferred to give weightage to economic geography, which would require a hill-plain stitching.

Within and without the second CA, over the years, there was an absence of open debates between the plains federalists and the mixed-region federalists. The latter argued that the density of poverty was to be found in the plains, that one must link the Tarai/Madhes to the north (either all or part of the way) so as to guarantee that hill-based resources would, by right, subsidise the plains. The plains citizens never really got to hear this argument.

Equalisation principle

Many personal, collective and institutional failures have contributed to the band-aid, patchwork exercise that has been Nepal’s constitutional writing as a whole and federalism demarcation in particular. But at the heart lies the refusal to take the identity vs. economic geography debate to the Madhes heartland of central-eastern Tarai, which in turn vitiated the delineation countrywide.

It bears keeping in mind that once the federal demarcation is locked in the promulgated constitution it will be difficult to reverse, because no well-off province will want to surrender natural resources and privileges already granted. The time to save the future is now, before the key is turned.

Given the extant suspicions, the demand for hill-plain linkages must come from activists and politicos of the plains. In the past, there has either been a judicious silence among the plains-based intelligentsia in the face of identity-based populism, or vociferous demands refusing to countenance even the hint of a hillock in the future plains province(s). At long last, some murmurs of circumspection have emerged in the last few days as the map of Province 2 got shared, but that will not be enough to carry the day.

The moment is penultimate, and this may be the time for Madhesi stalwarts who have kept their own counsel thus far to speak out. Meanwhile, those who went to the Supreme Court with the writ petition to block the formation of a federal commission of experts by the constitution framers may themselves want to seek a ‘vacating’ of the stay order that was granted. This would make it easier for the CA, if there is violence and deadlock, to leave the task of final demarcation to such a commission, basing itself on the issues as debated in the Assembly.

If, as seems likely, nothing will prevent the federal demarcation as proposed from being adopted, we must work to ensure that the ‘equalisation’ principle is applied. This principle would require the centre and provinces to join to subsidise provinces that are resources poor and with high volume of material poverty. Province 2, for one, will need to benefit from such an equalisation formula.