From Nepali Times, ISSUE #855(21 April 2017 – 27 April 2017)

The world does not understand Nepal, and Nepalis do not understand the world. We need translations both ways.

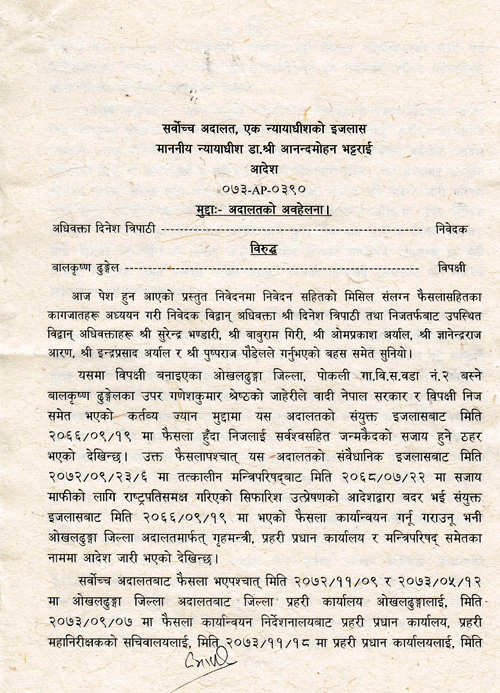

There is one factor that makes the Supreme Court of Nepal, much in the news lately under the stewardship of Chief Justice Sushila Karki, different from every other highest court in South Asia. The Sarbochha Adalat hands down its decisions in the vernacular (Nepali) rather than the Queen’s English, a reminder of the much more ‘organic’ evolution of our state as compared to the neighbours.

As with the media, which too has found its feet in the vernacular, this factor makes the court system more connected with citizens. The judgements and orders, though complex and with a lot of Sanskrit and Farsi terminology, resonate with the public for not having to be mediated by translators.

The downside of the use of Nepali as lingua franca, including the tongue of the judiciary, media and education, is that society has become insular, less and less exposed to the world even as the need to engage internationally gains urgency. Further, the outside world, including our two powerful neighbours, fails to understand and appreciate the challenges confronted and victories achieved by the people and country.

The Supreme Court of Nepal was set up and energetically led by Chief Justice Hari Prasad Pradhan, brought in from Darjeeling in 1951 by then Home Minister BP Koirala. It stood its ground on occasion even during the Panchayat regime, and in the loktantrik era, the Bench has handed down landmark judgements to this day on a broad range of issues, from human rights to gender, contempt, constitutionalism, accountability for conflict-era excesses, etc.

Nepal’s law-and-justice fraternity, including the judges, do refer to precedents from elsewhere, particularly the British and Indian courts and their modern common law system. The reverse, however, never happens, even though other court systems would certainly benefit from precedence set by Nepal’s justices.

The main reason for this is that legal practitioners internationally are largely unaware of these judgements. If our polity were more stable, more able to focus, in such a world there would have been immediate translation of significant judgements into English, available to be applauded or critiqued beyond the borders.

The same can be said of the media. Nepal’s English news/opinion has its role to play, but the people at large follow the Nepali language media in print, television and radio – with radio also coming on strong among the ‘national languages’. There is some translation of journalism available selectively, and at some cost, to the Western embassies, but there is just no way to take the pulse of the Nepali polity other than through a steady diet of Nepali language news and opinion.

One reason that the diplo-donors in Kathmandu, and through them the larger international community, have failed to adequately appreciate Nepal’s efforts to stabilise politically – challenging demagogues and interventionists alike – is that the narrative and discourse are almost entirely in Nepali. That is one reason why the international media and diplomacy did not notice while Nepal was reeling under the Great Blockade of 2016. The tree fell in the forest, but no one heard it fall.

The ascendancy of Nepali as the bridge language over the last century has created a vernacular that binds the populace, but the process has also left us intellectually poorer. Nepali has a published corpus of no more than 50,000 books and of that a majority would be fiction, religious tracts or travelogues. Rigourously penned non-fiction treatises are few and far between, and this has resulted in a weakened intelligentsia.

Some decades ago, a significant portion of Kathmandu’s literati was proficient in Hindi and Bengali, even when it did not have command of English. This was because many had participated in the urban milieu of Banaras, Patna and Kolkata. This opened the gates of outside knowledge, and osmosis ensured that modern thinking entered the Nepali slipstream. Kathmandu read novelists, shayars, political thinkers and journalists in Hindi, Bengali and English.

With the ascendancy of Nepali, including instruction in the school system, that particular window on the South Asian world is gone. During the Panchayat era, the English dailies and magazines of India arrived late afternoons at the Pipalbot in New Road, and discussions every evening in the tea- and coffee-shops would be vibrant.

The rise of the Nepali language media has led to a sharp drop in the reading of Indian papers, except for the Hindi periodicals consumed in the Tarai-Madhes, and we are all the poorer for that. Online journalism on the internet makes Indian and overseas media available on the fingertips, but they do not get the clicks.

We must seek multiple paths through which Nepal is portrayed internationally, honestly, warts and all. Simultaneously, we must seek to keep abreast with world events, to be able to respond properly.

We need a massive translation movement, with a dozen or so English works of fiction, non-fiction, classics and contemporary writings, translated into Nepali every year to educate ourselves. To educate the world, we can start by establishing a system to translate key Supreme Court judgements into English, immediately after they are delivered.