From HIMAL, Volume 5, Issue 6 (NOV/DEC 1992)

Mountaineering has not even begun to live up to its economic promise in the Himalaya. Decades of publicity about difficult climbs by elite mountaineers has kept ‘holiday climbers’ away. Encouraging easier, more commercial climbing, could prove lucrative to Himalayan countries if their governments, tourism industry and native climbers took advantage.

by Kanak Mani Dixit,

with reporting by Dipesh Risal

In early October, as every year, the people of I Kathmandu Valley enjoyed the festival of Dasain largely unaware of the dramas being acted out high above them, on the snow, ice and rock of the Himalayan massifs. Autumn brought 750 mountaineers employing thousands of native support climbers and porters from among 76 officially registered expeditions. Some were climbing alpine style, others were doing it solo with or without oxygen. Yet more engaged in the classic seige-style assault. As in every season, there was triumph and heartbreaking tragedy in the High Himal.

But for most Nepalis, fed only on Radio Nepal’s curt announcements of deaths, ascents and expedition failures, mountaineering has not yet come to life. It is a great divide that separates the native population and the climbing world — a chasm of history, culture, economy and socialisation between the local who is content to look up at Gauri Shanker (7134m) in reverence, and the mountaineer who would gladly set foot on (or near) that corniced summit if only the Ministry of Tourism would allow it. Spiritual distance, indeed, marks the attitude of most of the Himalayan peoples towards the snow peaks.But if they remain blase about the mountains, they cannot remain so about mountaineering. Developments in technology, information, geopolitics and economics together are changing the face of Himalayan mountaineering and the regions people and policy-makers can no longer afford to overlook its economic importance.

Going Himalayan Alpine

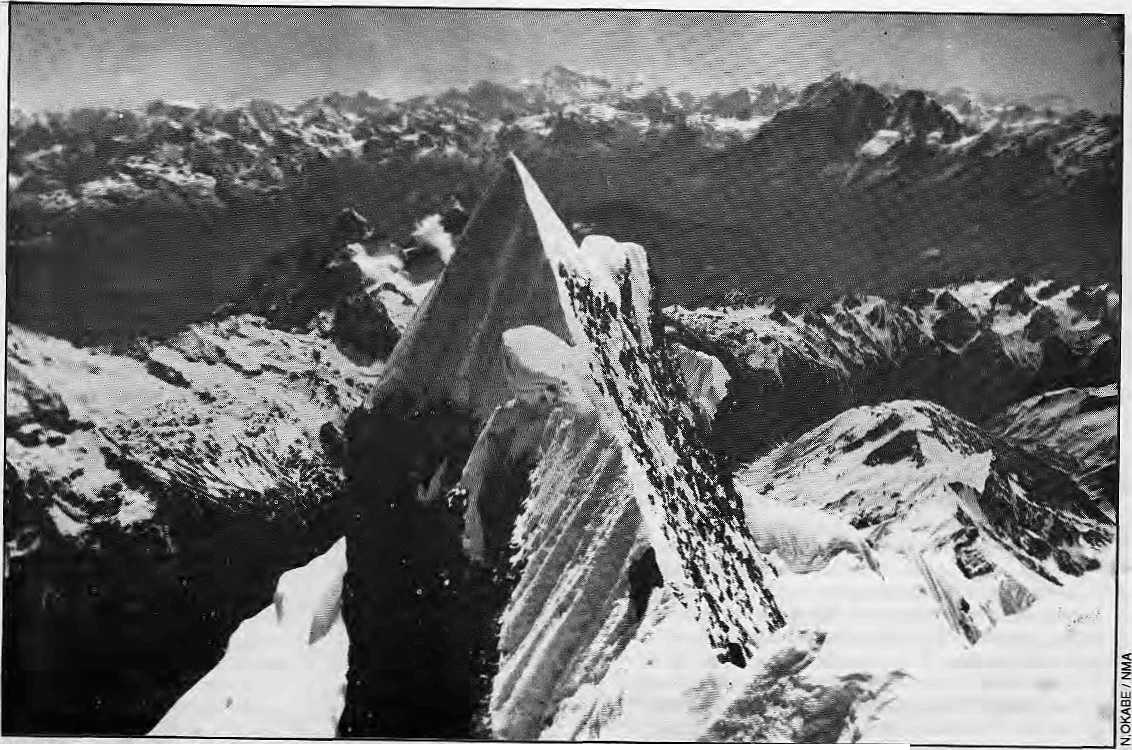

| CHOMOLONGMA = SAGARMATHA = EVEREST |

It has been 40 years since Himalayan mountaineering started in earnest. In 1950, Annapurna One (8091m) became the first mountain over 8000m whose summit was reached. Chomolongma was topped in 1953, and all 14 eight thousanders’ had fallen to Reinhold Messner by 1986. As little as two decades ago, the seige-style attempts characterised by the pre-War expeditions of the 1920s on Chomolongma were the norm. These militaristic assaults, heavy on logistics, are, now largely pass and the vanguard climbers have developed alpine style techniques of varying degrees of difficulty. A pure Himalayan alpine style attempt involves a fewer climbers than traditional expeditions, the minimum use of porters on the approach march, the least impact on the terrain, no Sherpas above base camp, no oxygen, and use of bivouacs where others rely on a line of fixed camps. This style — “bold, light and fast” as one writer described it — has been perfected by the likes of Reinhold Messner (who everyone knows), Voytek Kurtyka (who few do), Doug Scott, Tomo Cesen; and a long list of others who are deceased — for the Himalayan alpine style is a dangerous technique.

Even while alpinists stretch the limits of what is possible, however, the “coffee table climbers” continue their seige on the peaks. An example was the much-hyped British Telecom-supported team on Makalu in spring 1992. This expedition— a “dinosaur of an earlier age” as one magazine called it — failed on the planned West Face and again when it shifted to an easier route. Ultimately, as consolation, it cleaned up the mountains base camp of garbage and helicoptered sackfulls to Kathmandu.

Alpine style assaults today account for about half of all expeditions to the Nepal Himalaya. Pertemba Sherpa, Chomolongma summitteer and trekking executive, believes that peer pressure and high costs will make seige-style assaults rarer. “Soon, more than 75 percent of expeditions could be in alpine style. The growing popularity of lightweight expeditions will mean that the employment of Sherpas will fall drastically, but it has been my experience that assaults without Sherpas are seldom successful.” The change of style has other repercussions too, pointed out Khadga Bickram Shah, the non-climbing founder-President of the Nepal Mountaineering Association {NMA). “The alpine system is ethically great for them, economically the worst for us,” Shah said. The hottest topic to discuss, however, is not about alpine style or seige-style, but about the possibilities of guide- led commercial climbing.

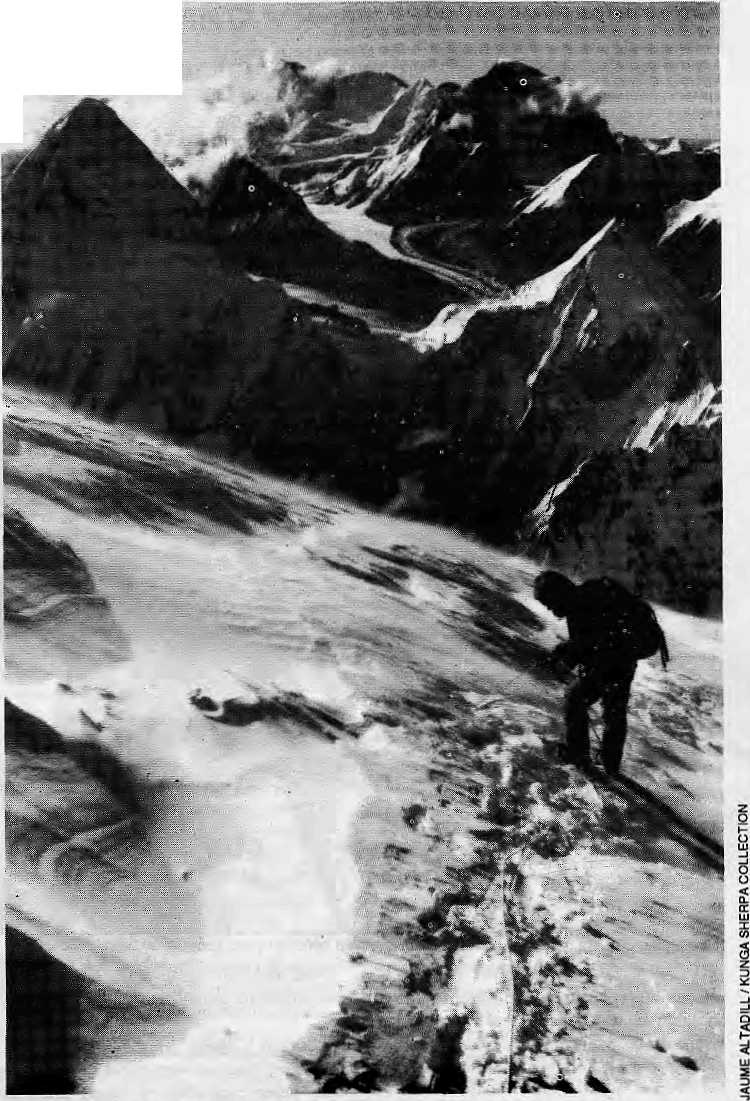

CLIMBER

Mingma Sherpa ,

Khumjung.

Together with Ang

Dorje, first Nepali

to climb

Chomolongma

without bottled

oxygen (1979),In

poor health, has

given up climbing.

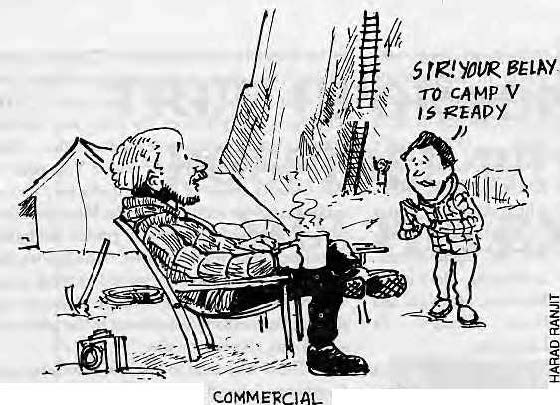

Packaged Climbs

Commercial mountaineering has already begun, with entrepreneur-climbers selling peaks like package destinations. Whether the purists like it or not, roost Himalayan climbing will go this way. The best that can be done is to ensure that local people benefit, that the mountain environment is preserved, and that the climbers sense of freedom does not suffer. In a commercial climb, the travel company (mostly Western, subcontracting to local agencies) arranges everything, including the permit, Sherpas, transport, equipment and route selection. The “clients” need only bring their personal gear. The difference from “private climbing”, whether seige or alpine, is that here clients are led by guides in much the same way as they are in the lesser peaks of the Alps.

The word is spreading, and holiday makers who might otherwise have gone for a couple of weeks climbing in Chamonix or Zermatt are beginning to consider a month in the Himalaya. The advertisements beckon from the climbing magazines. One company offers Changtse (7553m), the distinctive north peak of Chomotongma, for £ 3650 London-to-London, in a 50-day trip billed as “A climb in the shadow of Everest.” Muztag Ata (7546m), near Kashgar, is also on sale, “a very straightforward high altitude adventure above the Silk Road”. An unclimbed 6247m peak in India goes for just £ 1980 door-to-door. In the Khumbu, Ama Dablam (6856m) could be the Matterhorn of the Himalaya, with Western climbers lining up to climb. Some New Zealander climbing guides are already selling the peak, as it can be climbed (weather permitting, after about 10 days of acclimatisation in and around Pheriche village) in just three days from base camp.

Today, even Chomolongma is on sale, and the premium is high. On 12 May. For U$ 35,000 each, two American guides escorted a handful of clients to the summit via the standard South Col route. Sisha Pangma (Gosaithan, 8013m), the Tibetan peak which lies north of Kathmandu, is probably the most attractive eight thousander for commercial entrepreneurs. In late September, there was a bevy of inexpert Spaniards on the mountain trampling a virtual highway to die summit. According Kurtyka, the Polish alpinist, the South Face of the mountain “is the shortest and quickest existing line to an 8000m peak…for a busy man, it is a dream ground to flash an 8000m peak…”

Steve Bell, a proponent of commercialisation, has no doubt that this variety of climbing is here to stay. As lie states in Mountain magazine, “These (commercial) trips are not for hard climbers out to make a name for themselves. They are designed for the vast body of mountaineers who want a personal challenge with a minimum of hassle.”

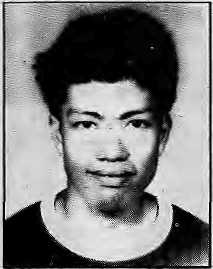

CLIMBER

Ang Rita Sherpa,

Pangboche.

First Nepali

woman to scale

major peak

(Lamjung,

6983m

The Nomenklatura

Himalayan mountaineering is manned by ‘Sherpas’ but devoid of native observers and analysts. In India, there are a few among the many amateur climbers who, at least, have the background and interest to discuss issues important to climbing. Harish Kapadia, who edits the Himalayan Journal from Bombay, is one of a few who scrutinises the mountaineering scene independently of the officious old-boy network that manages climbing through the Indian Mountaineering Foundation (IMF), In a field dominated by Western observers, Kapadia writes with a regional perspective. In a recent issue of Mountain, he scathingly criticised climber Peter Hillary (Sir Edmund’s son) for producing “one-sided mountaineering literature”. Kapadia continued: “Lately it has become fashionable to criticise the bureaucracy in this part of the world for the problems created by the climbers themselves…”

That is not to say that the Himalayan bureaucracy is above criticism. Whereas the IMF officials at least have experience of crampon on ice, Nepal’s officialdom is about as far as one can get, mentally and spatially, from the mountains. Yet these officers of the Mountaineering Section of the Ministry of Tourism control and administer over the grandest mountains on Earth.

A visit to the Ministry’s dismal offices, behind the Kathmandu sports stadium, can be disheartening. Routes are assigned on the basis of a dog-eared and disembodied Japanese book, Mountaineering Maps of the World. Only current information on ascents, failures and deaths are available and there is no library, background information or data. “The real problem is that we lack a computer,” confides one official. Things are no better at the presently headless Nepal Mountaineering Association (NMA), which had over the year become a den of bickering among non-climbers and recently collapsed under its own weight. When someone comes along asking for information, the standard refrain at the Ministry, the NMA, and the trek agencies is: “Go ask Miss Hawley.” They are referring to Elizabeth Hawley, who has lived in Kathmandu for 32 years as news correspondent, Executive Officer of Edmund Hillary’s Himalayan Trust and chronicler of Nepali mountaineering.

It is not necessary that a mountaineering official himself/herself be a mountaineer, but some first-hand experience and empathy would help when it comes to defining policy. Lacking such sensitivity, officials are easier swayed by exaggerated claims or misrepresentations by climbers, tourism business interests, and so-called mountain environmentalists.

For all its other weaknesses, the Nepali Government has been at the forefront of setting up mountaineering regulations, the very word being anathema to Western climbers who suffer restrictions only under duress. The system of permits, royalties and liaison officers, for example, were perfected by Nepali bureaucrats and now are de rigueur all over the Himalaya. When China decided to open up Tibetan mountains in the late 1970s, it sent a delegation to Kathmandu, literally, to learn the ropes. Says NMA’s former President Shah, “There is a great divide between the climbing nation and the Himalayan nation. They tend to view mountaineering from the European experience, where there are no royalties, no strict rules on porters, and no liaison officers. Ours is a professional mountaineering system, and theirs is a amateur system.”

CLIMBER

Narayan

Shrestha, Kavre.

First Newar on

Chomolongma,

Summer 1985

Deceased,

Nepali officials, too, are matter-of-fact about treating mountains as an economic resource. “For them it is a sport, for us it is a tourism product,” maintains Prachanda Man Shrestha, who ran the Tourism Ministry’s Mountaineering Section for six years till 1990 and is today with the Department of Tourism. “The Government views that mountaineering activities must be used to provide economic opportunity to remote areas. Mountains are an asset to the country’s economy generally, and they also provide direct revenue to Government.” At the annual meets of the international association of alpinists, UIAA, and elsewhere, the Himalayan representatives are smug in the knowledge that the mountains are in their command, which gives them unimaginable clout vis-a-vis the world of climbing heroes. As an Indian representative said to a Nepali member at a UIAA gathering a couple of years ago, “Baat chod yar! Akhir yeh log hamarahi to aana hai!” (Let them goo n! All said and done they have to come to us.)

Himalayan Economics

Commanding as it does the southern approaches to an entire section of the Central Himalaya, the Nepali Government is well placed to set monopoly prices. But it is doubtful that the Tourism Ministry can fine-tune its policy to maximise benefit from mountaineering. With commercial expeditions showing the road to the future, officials have to carry out a serious cost-benefit analysis, to arrive at the rates that will bring in climbers of the right spending category.

The sum the Government collects from royalties alone was a little under a million rupees in 1982, rose to NRs 4.3 million by 1987, and was NRs 9 million in 1991. In Spring and Summer of 1992 alone (following the latest hike in royalties), it earned NRs 11.7 million from its mountains, this figure excluding fees collected separately by the NMA for the so-called trekking peaks.

CLIMBER

Sungdare

Sherpa,

Pangboche.

Five-time

summitteer of

Chomolongma

Deceased

It may not be too late for the Nepali Government to mull over whether it is in its interests to be regarded as the Scrooge of the Himalaya, milking impecunious mountaineers whose only fault is that they want to climb here. It is now already Impossible for climbers of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to set foot on Nepali mountains, and an ambitious Russian plan to do the Everest Horseshoe (ridge-climbing from Nuptse to Lhotse to the Chomolongma summit) in 1993 seems to have been scrapped after royalties were raised. For now, Nepali peaks are much more costly than their Indian siblings. While Chomolongma goes for US 50,000 starting in Spring 1993, India’s most expensive East Karakoram peaks cost U$ 5000 apiece, while the Nun and Kun peaks in Zanskar cost U$ 2250 each. All other peaks in IndiarangefromU$900toU$ 1800,while peaks below 4500m earths climbed for free. In contrast, Nepal’s eight-thousanders are priced at US 8000, those between 7000m and 8000m cost U$ 3000, 6500-metre to 7000-metre peaks cost U$ 2000, those between 6000m and 6500m are set at U$ 1500, and peaks below 6000m cost US 1000. The market will either force Nepal to ultimately reduce royalties (other than Chomolonga, which is a product apart), or India will follow suit and hike up its own prices. No one is yet talking of a “mountain cartel” that coordinates royalties and mountaineering regulations.

A Growth Sport

The greater availability of information and the confidence that comes with it, technological advances in mountaineering equipment (see page 17) and the opening up of new climbing areas are leading to more arrivals in the Himalaya, but the pace could be quickened with better public relations and marketing. Unlike in the 1950s and 1960s, mountaineers need no longer waste weeks on the approach march. In Tibet, they can truck it to the base camp of most peaks while, in Nepal, turbo-prop aircraft drop climbers off much closer than the road heads in the Tarai where erstwhile adventurers such as Eric Shipton and Maurice Herzog had to begin. Herzog’s 1950 French expedition to Annapurna One found a mountain range blocking the way where the map showed “an easy cow path”. Even though maps available today also leave a lot to be desired, mountaineers have access to aerial pictures, satellite images, and in the case of Chomolongma, a detailed 20-metre-interval contour map.

With increased demand, the governments of the Himalaya will respond by opening up new peaks (except, for the moment, the Indo-Pakistani mountain border, and Bhutan). As Indo-Chinese tensions ease, and with individual Indian states demanding their share of tourism income, Inner Line restrictions are being relaxed. With its announced economic reform policies for Tibet, the Chinese can definitely be expected to open up more peaks.

There are so many mountains out there. Nepal alone has 1310 peaks above 6000m, of which 118 are open today. “Taking into consideration the mountaineers being concentrated in the Eastern region and to diversify the mountaineering activities,” the Nepali Government announced in August that eight more peaks from 6500m to 7000m will be available in the west Nepal districts of Darchula, Humla, Bajhang and Dolpo, Whereas till now only three climbing seasons had been recognised, the Government also decided that the summer season too would be open for mountaineering expeditions, which means that climbing can now be year-round. Winter climbing in the Himalaya used to be considered extreme, but today it is an established, albeit difficult, sport. Perhaps the new frontier will be climbing in the monsoon, with its special challenges such as danger of avalanche.

Plan the Future

For all the awe that extreme Himalayan climbing garners, the bulk of mountain tourists do not come to the best mountain system in the world. There exists a large clientele between the US 12-a-day trekker (who the Kathmandu agencies are scrambling over today) and the U$ 35,000-guided climber on Chomolongma. The sales pitch has to counter decades of incessant coverage of the heroics of Himalayan climbing, which projects the severe conditions and convinces amateurs that they need not apply. The books, lectures, trade magazines and journals are all about extreme hardship climbing. Only recently have some writings emerged on the world of intermediate Himalayan climbing. A significant new book is Bill O’Connors Trekking Peaks of Nepal (Crowood Press, 1989), which describes routes on peaks such as Pisang and the “Chulu sisters” in Manang, Mera in the Khumbu, and Yala and Naya Kanga in Langtang.

At a time when the talk is only about bagging eight- thousanders, the world of the holiday alpinists (who number in the tens of thousands rather than the hundreds who today come to the Himalaya) must be told that there are faces here between 6000m and 7000m waiting to be climbed. Once you get over the altitude factor, the Himalaya need not be all that different from other more popular lower ranges of the world. On 90 percent of the existing routes, says Roddy Mackenzie, a Chomolongma summitteer and heli-skiing entrepreneur, you do not expect to fall, although you do need protection. Writes author O’Connor, it is now possible for “an individual or group of friends to take part in or organise their own expedition within the context of a few weeks annual holiday with the minimum red tape or expense.”

CLIMBER

Chewang Rinzi

Sherpa,

Namche.

First Nepali to

scale

Chomolongma

from North face.

The lack of standards in the local trekking and mountaineering vendors is a major hurdle to be overcome on the road to commercialisation. Competition among trekking agencies is rife and undercutting is the rule. These conditions encourage many businesses to cut corners, providing inexperienced porters, bad equipment and little backup in case of accident. Every year, therefore, scores of climbing teams return home dissatisfied and spread the word of an industry that has yet to know what is in its long-term interest. The climbers themselves help little by shopping around for the cheapest agency, mostly to be found in and around the Thamel tourist quarter. Once on the mountain they are apt to find that their guide1 has never been above 12,000 feet and is sickly to boot. He drops out, and the porters start agitating to leave for home. Three Australian women on their way to Yala peak in mid-October spoke of the difficulty they had in finding a proper mountain guide. More than one agency promised experienced guides, but failed to produce them for interviews. “The few we did meet were not the sort we would trust our lives with on the end of a rope. In the end, we put up signs in Thamel lodges and went by the advice of a returning climber we met.”

Those who tend to lose out in a cheap and ill-organised climb are not even the sahebs, but the lowland porters. For it is they who take up the slack by having to carry more loads, sometimes even to high camps. While some trek agencies provide adequate clothing. Chinese basketball shoes, and even cheap dark glasses, the majority go up the mountain unprotected and innocent of the dangers. A big and unexpected storm over the Himalaya puts porters right across the chain in great jeopardy. While the Tourism Ministry keeps records of those killed on the mountain, there is no one maintaining figures on porter deaths along the trails of Nepal.

CERTIFICATION

In the world of commercial climbing, it will no longer suffice to glorify the Sherpas and to bank on their name and effort. The Sherpa ability is in mountain travel, through awkward moraines and steep slopes. Sherpas are, as one Western climber says, “great plodders”. They are well-acclimatised to Himalayan heights, used to carrying incredible loads, and wizards of seige-style logistics. For the future, however, Sherpas and other would-be native climbers need to be better at technical climbing, which comes not from portering on snow, but from climbing rocks and handling ropes. Unfortunately, an understanding of the science of climbing, from the optimal angle required for an ice anchor to recognising the symptoms of AMS, does not come easy with a Nepali village-school education.

A whole new world will open up to native climbers once their technical ability is enhanced and they receive an UIAGM certificate or equivalent (see page 28). Until that day arrives, however, Western guides will continue to take clients up the peaks, Ama Dablam at U$ 200 a day or U$35,000 ‘per pax’ on Chomolongma. At present, a handful of Nepali climbers have taken some of the stringent UIAGM courses at Chamonix, but none have been certified as professional International Mountain Guides.

The few climbing schools in the Subcontinent, in Uttarkashi, Manali, Darjeeling and the NMA’s own in Manang, are producing amateur climbers, not qualified guides. Says Tashi Jangbu Sherpa, who has taken some UIAGM courses, “Getting a certificate from Manang has become just like taking a computer course. But you do not get qualified just by getting a certificate, you have to climb mountains and gain experience.” Another Nepali climber says he knows of “at least 15 certificate-holders who have not climbed a single peak.”

CLIMBER

Sambhu

Tamang,

Sindhupalchowk.

Youngest

Chomolongma

summitteer

(1973) and also

first non-sherpa

Nepali on top.

If the mountaineering industry expands as envisaged in the coming decade, it will grow beyond the numerical capacity of the Sherpa community of Nepal to fill. And as is already happening with Tamangs and Gurungs today, more hill communities are going to be joining the lucrative trade. There is a sense of uncase among some Sherpas that a trade they have nurtured for so long (since the British picked up their ancestors from Darjeeling tenements in the 1920s), might go out of their grasp, to be taken over by “rongba” lowlanders, both in terms of sardaring and operating treking agencies in Kathmandu. Occasionally, non-Sherpas climbers, too, complain about Sherpa dominance and reluctance to allow others the lucrative positions on expeditions. There is also exasperation with the Westerner, for whom every native with a pack on his back is a Sherpa. “They want only Sherpa, so we become Sherpa,” said one Gurung sardar recently en route to the trekking peaks of Manang.

But resentments are not as deep as one might expect, probably because the market is expanding rather than shrinking. “It is good that non-Sherpas are getting involved,” says Pertemba Sherpa. “So far, the number of non-Sherpas is quite high in trekking and not in climbing, where you need to be physically adapted to high-altitude.” Adds Ang Tshering Sherpa, trekking executive, There is always a demand for people in this profession, so there is no friction between Sherpas and non-Sherpas.”

Trickle Down

Does the benefit of climbing trickle down from the mountain to the surrounding landscape and population? Or does it just trickle down to the commission agents in Kathmandu? If it is true Kathmandu? If it is true that the first to benefit from climbing must be the people around the mountain itself, then Himalayan climbing is largely equitable as far as the Sherpas of the upper Khumbu are concerned. But a look at the order regions of the Himalaya indicates that close closest to a mountain chain do not necessarily benefit most. Part of this may be due to lack of interest and part of it may be not knowing how to take advantage. For both these reasons, and for the expertise they have developed in climbing and logistical support, Sherpas today help in climbs rights across the Nepal and Indian Himalaya, in Tibet, as well as in the Karakoram. And Sherpas will continue to provide the backbone of Himalayan mountaineering for the foreseeable future.

While there is u need to ensure that there is vertical equity (by class) and horizontal equity (by community) in the mountaineering trade, no one expects the Government to play an activist role. And unionising will not work. Attempts by porters to organise right after the advent of democracy in Nepal in 1990 were promptly short-circuited by political divisiveness and external pressure. The regional academia and media are both too far removed from mountaineering as a trade, although the Tribhuvan University has just begun courses in tourism which might lead to some ongoing monitoring of the trade. The only players left, then, are the trekking industry executives, who come in an incredible variety, from Chomolongma veterans to Kathmandu Valley lowlanders who have been above 3000m only on an airplane. The social commitment of trekking agency operators tend to vary widely, and the majority has little time for vicarious concerns in the rush rounder cut the competition.

One should not, of course, over-emphasise the exploitativeness of mountaineering and trekking agencies. After all. they bring cash income to a population that has few other alternatives. Nepali men and women are able to work in their own mountains and to earn an income as a direct quid quo pro for the energy they burn. However, equity has also to be seen in terms of the total profits made by the trade and its distribution. And portering in the Himalaya is probably the most excruciating of labours in the world. Neither is anyone counting the. income earned in relation to the high cost of food and shelter on the trail, the opportunity costs, depreciation of clothing and footwear, and, most importantly, the wear and tear of the body. With all these factored in, the income of portering is not as high as it is made out to be. Thus far, no one has come forward to help porters do a proper cost benefit of their labours.

Pseudo-Nationalism

The intellectual non-climbing circles in Kathmandu often latch on to the theme that for all the trouble that the Sherpas take in assisting the sahebs and memsahebs to the top, they do not get their share of the income nor of the fame even as the foreigners go on to write books, do lecturers and buy castles in the Tyrolean Alps. Some of this concern is justified, some misplaced.

Among Sherpas, but almost never reported in the climbing press, there is the inside story of climbs that their clients would rather not have discussed. It is significant that practically all climbing reports in the magazines are first-person accounts, and only the native climber knows what is omitted. But blowing the whistle would be bad for the next seasons employment, so the Sherpas keep silent on who had taken swigs of bottled oxygen on aa no-oxygen climb, who had Sherpa support most of the way on a solo climb, and the many who had to be dragged and cajoled to the top so that they could be heroes and heroines back home.

CLIMBER

Ang Rita Sherpa,

Thame.

Seven-time

Chomolongma

summitteer.

Marc Batard’s famous solo climb of Makalu (8463m) is a case in point. The most difficult parts were fixed with ropes a couple of days earlier by Batard and his partner Iman Singh Gurung. As the latter recalls the climb, on 24 April 1988, “We had just got to the top of the French Pillar at 8000m and only an easy climb to the top remained. The weather was great and it was only noontime. Suddenly Batard said he was extremely tired, and we just had to descend. I was shocked, but there was nothing else to do. He insisted.” Once down, Batard confided that it was important for him to go up solo. The weather held, and the next day the climber shinnied up the fixed ropes to the lop, and to much adulation in his native France.

The Nepali mountaineering establishment has occassionally tried to glorify the achievement of Sherpas. In 1953, Tenzing Norgay was feted in Kathmandu, songs were written about his heroics (and how he supposedly pulled Hillary to the top, and so on), but in the end Norgay was unceremoniously dumped for having “defected” to India. Much later, the NMA tried to lionise Sungdare Sherpa, at one time putting him in display at a travel meet in the West Germany, recalls one German writer, “as if he were a specimen on display.” As former NMA President Shah concedes, “We tried to promote Sungdare Sherpa, but we realised that we had burdened him with something for which he was not psychologically prepared.”

The Nepali Government has done what is within its powers to recognise climbing achievement, says one official. “We made sure that they received the highest national awards— the Trishakti Patta and the Gorkha Dakshin Bahu, both First Class.” But, says Tashi Jangbu Sherpa, “the medals are not very useful. You raise their spirits, give them high hopes, make them briefly part of Kathmandu’s cocktail circuit. But in the end, they have to return to reality and go back to toil on the mountains. So frustration builds, and drinking begins.”

It is actually surprising how little Sherpas have been used by the commercial world for marketing and promotion. That, at least, might have brought some ancillary income to the famous Sherpas such as Sungdare, Ang Rita and Ang Phu. Instead, a delivery van manufactured in England and a Nepali bathing soap have been christened “Sherpa”, and no one is talking of royalty. A couple of years ago, a Nepali public relations man did try to “market” Ang Rita, seven-time Chomolongma summitteer. He wrote to famous corporate sponsors in the West, but the interest just was not there.

When native climbers are asked what the mountaineering establishment could do to assist them, they invariably speak of the need for a welfare scheme: old age pension and disability coverage. For the moment, old climbers and those whose health goes bad return to their home village and to work as subsistence fanners — to re-live old glories momentarily when the occassional Western climber comes looking for them to pay homage and to reminisce.

Climbers from the world over will continue to come in increasing numbers to the Himalaya. As for the locals, the porters do not know to do any better, and the native climbers and sardars will continue to serve as untrained, underpaid support staff. The trekking agencies are willing to undercut each other and scrabble around for leavings. The majority population, meanwhile, continues to regard the mountains from a spiritual distance, while the governments use the peaks to top up die national coffers and to promote pseudo-nationalistic pride of the Himalayan heritage.

It is time that the people of the Himalaya appreciated the mountains both for the challenge of climbing that they pose, as well as for the fair and distributive trade that it has the potential to offer, at a scale much larger than the most trekking agents of today are able to visualise.

Mountain Rescue

Setting up mountain rescue in the Himalya is a little like the chicken or the egg story. Do you set tip expensive rescue facilities to attract climbers, or allow the industry to grow and justify the infrastructure. The larger expeditions have been able to take care of their own rescue operations, but lighter and “commercial” mountaineering will make more demands on independent rescue and evacuation procedures. In Nepal, the role of the Himalayan Rescue Association (HRA) for the first two decades of its existence has primarily been limited to tackling acute mountain sickness (AMS), with public information and through seasonal health posts in Manang and the Khumbu.

Unlike in the Alps, where helicopters are able to hoist climbers off the mountain, the thin atmosphere above 6000m means that primary rescue will always have to be by fellow climbers and guides. Airborne rescue above base camp are mostly not possible.

In a dramatic rescue on 26 June this year, an Indian Army helicopter picked British climber Stephen Venables from Panch Chuli V (6349m) in the Kumaon Himalaya. Pushing the limits of the helicopter’s abilities, the pilot balanced one skid on a glacier slope while fellow-climbers bundled Venables aboard. Probably the most dramatic ‘self-rescue’ in recent years was Doug Scott’s, who with both legs broken, dragged, abseiled and jumared himself down from near the summit of Ogre (7285m) in the Karakoram, and finally crawled on all fours over three miles of glacier to base camp. “It was a severe lesson which I was lucky to survive and can not anxious to repeat,” he said later.

It would be too much to expect the holiday climber to be as lucky as Venables or as tenacious as Scott, and the Himalaya will not attract the large numbers envisaged until better arrangements can be made for rescue. As the number of climbers increases, it is possible that the HRA could find it possible to maintain a helicopter dedicated to rescue. Developing special stretchers that can be balanced on the back of yaks, the availability of Gamow Bags for rental in Kathmandu shops, and training local guides on rescue and trauma treatment, are the other activities that would promote confidence of lay climbers.

Gurkhas as ‘Sherpas’

As Gurungs, Tamangs, Magars, Rais and Limbus become active in Himalayan mountaineering, they will, in a manner of speaking, be going back to their roots. For as Gurkhas, the non-Sherpa hill people of Nepal have also been active mountaineers since the time they helped British empire chart and control the Himalayan region. As geographer Harka Gurung writes, it was in the 1880s that soldiers- of the 1/5th Gurkha Rifles were trained as mountaineers while serving in the North-West Frontier of India. These riflemen, according to Gurung, “became pioneers among Nepalese climbers.” (see “Gurkhas and Mountaineering” in NMA’s 1985 Nepal Himal and Himal Jul/Aug 1991).

The Gurkhas were first engaged in mountain exploration in 1889. when they traversed several till-then unknown glaciers in the Karakoram, The most interesting early Gurkha exploits were by Amar Singh Thapa and Karbir Burathoki, who together with some alpine guides “crossed 39 passes and climbed 21 peaks in 86 days of Alpine traverse”. A.F. Mummery’s 1895 attempt on Nanga Parbat (8125m) included two Gurkhas. The three never returned, and were believed to have been perished in an avalanche.

Gurkhas were also members of the successive expeditions on Chomolongma between 1921 and 1938. In 1922, Naik Tejbir Buda of the 3rd Gurkhas- spent two nights at 7772m on the mountain. In 1927, he received an Olympic medal from the President of France for his high altitude resilience.

All this was the distant past. These “amateur diversions” ended for the Gurkhas, writes Gurung, “with the passing of the gentleman alpinists they emulated.” As for the fume, mountaineering and trekking hold out the possibility of absorbing at least some of the surplus labour released by the planned phaseout of the British Gurkhas and reduced recruitments into the Indian Gorkha regiments.

While the non-Sherpa hill people of Nepal have concentrated in providing “lowland porter” support to mountaineering expeditions, some of their bretheren in the armed forces have been actively engaged in mountain climbing. The British Army, for example, has been training Gurkhas in the Alps for decades, and Gorkhas of the Indian Army serve in high altitude outposts, including the killing snow-fields of the Siachen Glacier.

In a unique mix of two of the motifs which define Nepal for many — the Gurkhas and the Himalaya — one trekking agency recently put out an advertisement inviting climbers to “Explore the highest snow mountain with the brave Gurkhas of Nepal”— using Gurkhas rather than Sherpas to sell mountaineering services. There seemed to be a bit of overkill, though. For when Himal called the agency, the voice at the other end was apologetic: yes, they had one Gurkha with them.

Good Gear Makes It Easier

During the second British expedition to Chomolongma in 1922, George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce used bottled oxygen for the very first time. The four steel cylinders and the supporting frame of each piece weighed around 14 kilogrammes, and the apparatus was both awkward and prone to clogging. That was 70 years ago. Today, the market is packed with modern, ultra-efficient and innovative equipment, some of which has undoubtedly contributed to making mountaineering more accessible.

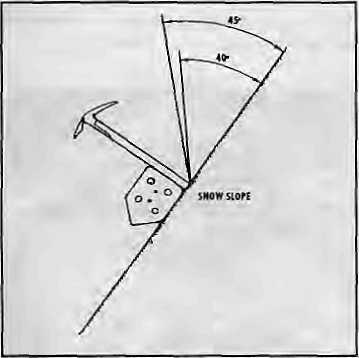

The ice axe, one of the indispensable tools of climbing, has seen remarkable changes since its early days. The ice axe of the early 20th century used to be quite long, doubling up as a walking stick on level ground. Nowadays, apart from being shorter, it is also provided with two or more holes for looping ropes. New alloys, resins and fibres, and combinations of these, have replaced the traditional wood and metal in the axe.

A decade ago, the “reverse curve pick” axe — the pick curving slightly upwards — became available. It is now considered to have been a revolutionary step in the design of ice-climbing equipment. Some shafts nowadays are bent, the plus side of these being that they reduce fatigue and protect the knuckles while attacking the ice, and the minus point being that they are less versatile because of their specialisation.

Researchers at Scotland’s Strathclyde University have developed safer ropes for the Cairngorm Climbing Company. A chemical dressing applied to the yarn used in making the rope changes colour when the rope reaches its UIAA designated number of falls. So, when the rope has been used for long enough, it turns black at the places where it has been weakened, warning the against an unprotected fall.

Gore-Tex is a synthetic membrane that has been used widely in mountaineering gear. Sheets of the membrane are used to line outdoor clothing. The clothing keeps the body surprisingly warm and dry while allowing moisture to escape through pores in the membrane. This material has also been used for shoes, sleeping bags and tents, with mixed results. Gore-Tex liners in boots help in drying up the boots quickly while on ice or moist ground. But in tents, it is less effective.

Rucksack design is increasingly ergonomic, geodesic domes provide more living space for a given floor area, and their alloy poles are light and strong. Harnesses for full-body, waist and kg have been improved although mountaineers complain they are inconvenient and restrictive and many prefer to tie ropes directly around their waists the old-fashioned way.

A noteworthy development in the Nepal Himalaya has been the easy availability of light, high-pressure oxygen bottles, coming from Moscow. After the Soviet disintegration, these cylinders, said to have been developed for the military, have penetrated the market and have become quite popular. Their selling point is that they are half as heavy as the regular European models,

On the life-saving front, perhaps one of the most important product of Himalayan climbing has been the Gamow Bag, a seven kilogram nylon chamber which resembles a pumped-up sleeping bag. It has been hailed as an effective life-saving, first-aid device for acute mountain sickness (AMS). The sufferer is placed inside the bag, and air is led in from an attached pump, simulating a descent of several thousand metres. Although intended as a temporary first-aid device only, the Gamow Bag, developed by a Colorado doctor, has proven valuable in many cases of AMS. The price of the Gamow hovers around U$ 2000, which presently restricts it to larger expeditions. However, word that other manufacturers are working on clones to sell in the below U$ 500 range holds out the possibility that this innovative hyperbaric chamber will lead to greater confidence among mountaineers to come climb in the Himalaya.

— Dipesh Risal