From HIMAL, Volume 8, Issue 6 (NOV/DEC 1995)

Bearing loads on the back the way his ancestors did fifteen thousand years ago, the Nepali porter carries an evolutionary legacy as well as a modern-day burden. Treating his condition would also cure the socio-economic ills of Nepal’s hill peasantry.

Three ragged labourers, hailing from the hills of far-west Nepal, haul a drum full of truck diesel up from the Lakadi Bazaar depot in Shimla. On the 15 km trail up from the Gaurikund bus stop in Garhwal, a Nepali ‘kandiwala’ carries his 2000th pilgrim up to Gaumukh, where the Ganga has her source. He earns ninety rupees for the effort. On the Lamjura Pass, the high point on the trail to Khumbu in east Nepal, a 44-year-old Rai man is in the middle of a ten-day haul, with a load that is more than twice his own weight.

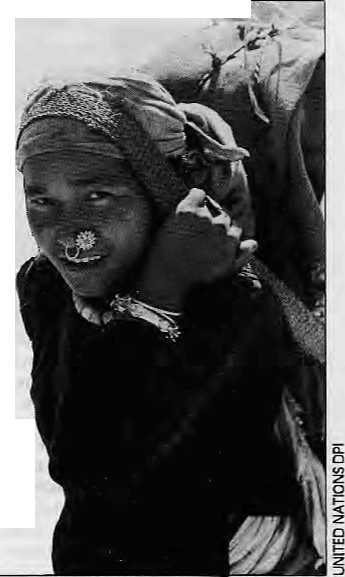

Every day, tens of thousands of Nepali porters in the middle hills carry excruciating loads on their spines, for the sahu merchants, for trekkers and mountaineers, and for development agencies. Hundreds of thousands more, heave the basket as part of their daily household chores, fetching water, firewood and fodder.

Carrying goods on the back with the help of a tumpline (namlo) is the most ancient, and taxing, of human labours. While the loads carried by Nepali porters are the heaviest anywhere in the world, the feat is doubly impressive when one considers his diminutive size and body weight. Himalayan back-loading is also distinctive because it is a continuous, unremitting activity, unlike, for example, the stevedore’s momentary toil.

Watch the Nepali porter, otherwise called a bhariya or dhakrey, on the trail as he grunts and sweats his way up a 50 degree switchback. Spine bent to receive the basket, hands clutching the namlo which distributes the load over his vertebrae, the muscles of the neck, calves and thighs taut – this is how they carried goods 15,000 years ago, before there were pulleys, levers and wheels.

Bhariya-work is a holdover from the evolutionary past of humans, a heritage which every other hill society has discarded for more modern forms of haulage. In the central Himalayan hills, the Nepali peasant’s namlo remains firmly in place as a stark reminder of the region’s economic history and geography.

As botanist Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha points out, porters have moved millions upon millions of tons of goods up and down the central Himalayan mountains, over millennia. The sheer volume of physical pain and mental suffering that has been expended on these mountain trails over the centuries is massive. And yet, this way of life and work has attracted scant attention from social scientists and development workers in Nepal, and elsewhere.

Hard Livelihood

From August 3-4 in Patan, Himal organised what turned out to be the first-ever meeting on the subject – “Hard Livelihood: Conference on the Himalayan Porter.” Worldwide, no more than a handful of researchers have taken an interest in the subject, and almost all attended to share notes and express strongly-held views.

Much of what emerged from the conference was new and surprising. Participants learned why collective bargaining has not worked for Himalayan porters, why Sherpas are better on the job in high altitudes, and how the philanthropic tradition of maintaining pati and chautari rest-stops for porters has died out. They also learned that modern transportation in the form of Tata trucks, Russian jeeps, Canadian Twin Otters and, lately, Mil7 helicopters, were engaged in wresting cash income from families surviving at subsistence through portering. And, they learned that the supposedly porter-friendly suspension bridges were actually taking away jobs, as yaks and mule trains took over.

One paper suggested that backloading was part of hominid evolution, and that it probably promoted “upright bipedalism” in humans – why we walk on two feet. A neurosurgeon’s report held out the possibility of using the namlo as a physiotherapy aid for those with degenerated upper spines. Another researcher was of the view that, despite the spread of roadways, portering would remain significant for at least 30 percent of the Nepali hills, beyond 2015.

Most importantly, it became clear that, economically as well as symbolically, the carrying of other people’s loads for an income is more than anything else, a manifestation of hill poverty and the failure of the Nepali state to be responsible for its underclass. These mountains would ‘develop’ only when the namlo is finally separated from the hundreds of thousands of Nepali thaplos (foreheads). The eradication of portering would indicate that the country was finally making progress.

Riding the Porter’s Back

Every hill family, other than the few well-to-do which are able to hire others to do the lugging, are porters. The daily trudge to the spring or water spout is portering, as is carrying a year’s supply of salt from the road head to homestead (which may take as long as a week!), or carrying kerosene or corrugated sheets for the hill market sahu. Trekking is the only business that offers porters the chance of some form of upward mobility – graduating from low altitude porter to cook to naike to sirdar. The stratospheric reaches of portering are occupied by the high altitude porters, mostly Sherpas, who assist sahibs in achieving summits.

Backloading, for all its ubiquitousness, is not visible in the country’s economic statistics. It is a commentary on how Nepali planners plan, that this activity has no profile in national programmes, other than what benefits percolate down through general ‘village development’ programmes. Pitamber Sharma, an economist with ICIMOD in Kathmandu, agrees that portering’s contribution to the economy goes unacknowledged: “While portering is contributing to about a third of household income of marginal families, it is economically invisible,” he says.

Why does human-back portaging survive in Nepal when it has disappeared elsewhere? In the Indian Himalaya, the need for human carriers was reduced drastically after the Border Roads Organisation went on a highway-building frenzy, following the 1962 war with China. The high cost of roadway construction, meanwhile, has prevented Nepal from developing a large network. As late as 1991, it had only 8328 km of roads of all types, which meant a density of 3.5 km per 100 sq km in the hills. Above and beyond the lack of roads, the precarious humans-only bridges of the gorge country denied access to beasts of burden.

The chief reason Nepalis porter is, of course, that they are poor, across the breadth of the country. Take the example of Prem Bahadur, from Rolpa district of west Nepal, who says he has been carrying pilgrims to Kedarnath for 49 seasons. He is a ‘kandiwala,’ who carries on the back. Speaking to Dehradun-based researcher Ramamurthy Sreedhar, Prem Bahadur said he had taken up portering to supplement his family’s income as the fields did not provide enough. He said: “I am cursed to carry human beings. I have carried thousands to the house of god, but bhagwan still will not see my plight.”

Nearly all the kandiwalas Sreedhar encountered in the Garhwal dhams (pilgrim destinations) were from the poor western hills of Nepal. On average, a porter ferries 700 well-fed pilgrims for darshan every season, earning about IRs 7000. What he saves after expenses is his ‘profit.’

“Because a porter by definition carries someone else’s burden, portering has remained symbolic of an inherently exploitative arrangement,” says Pitamber Sharma. “The true rural proletariat of Nepal is made up of those who porter for others.”

Bishnu Bhandari of the International World Conservation Union (IUCN), who this spring conducted a day-long workshop of bhariyas in north Gorkha, found that even the food they would save at home by joining a trekking group, was part of the economic calculation of the peasants. Said one porter, “If I go carrying loads, at least I am eating as I go.”

According to environmental activist Anil Chitrakar, “Portering is one of the few professions in the world where the more experienced you are, that is, the older you get, the less is the pay. Porters have neither insurance nor any political leverage. There is no pension scheme. They are on their own.”

Lhakpa Norbu Sherpa, a Khumbu ecologist, calculated the income of porters after the helicopters sent porter incomes crashing in the Jiri to Namche route. He found that the average daily income of the porter was NRs 155, out of which he spends NRs 74 daily, on subsistence. “It is no longer worth the pain, but they still continue to porter,” says Sherpa.

One community, which has historically been relegated to the portering life, is the Tamang, living in the hills that surround the Kathmandu Valley. Since ancient times, these people have been maintained as an exploited, unskilled underclass for use by Kathmandu’s cultured urban classes. Ben Campbell, an anthropologist from the University of Manchester noted, “The strategic role of Tamang communities in central Nepal was as an underdeveloped reserve of labour power, at the service of the central elites. Their marginal niche and subsistence economy were treated with neglect.”

Even though the trekking industry now provides work to many Tamangs, the Tamangs do not get rich from trekking, said Campbell. As he said:

“Many of the villagers who go ‘to carry foreigners’ loads’ come back with little to show for their work, at most a few hundred rupees, some new clothes, or some stainless steel plates. The details may have changed but the Tamangs are still carrying loads to make profits for the Kathmandu elite.”

What, No Union?

If the porters are at the bottom of the labour ladder, and make up a rural proletariat, why don’t they organise? These are the people who, after all, literally earn by the sweat of their brows. And yet, several factors conspire to ensure that Nepal’s porters have no collective voice.

Overwhelmingly, the porters of Nepal are uneducated and unrepresented. Because the workforce greatly exceeds demand, they have little or no bargaining power. They are divided among themselves by region, ethnicity and caste. Furthermore, there is no ‘factory floor’ where porters can gather, which facilitates organisation. By its nature, portering is a solitary rather than collective assignment.

The advent of democracy in 1990 did see some scattered work stoppages called by the Trekking Workers’ Association of Nepal, but organising efforts quickly fizzled out. The Rolwaling region and some villages elsewhere in the High Himalaya, do guard their trails to ensure high rates from trekking groups, but this has not been feasible elsewhere in Nepal.

Even in Baltistan in the Northern Areas of Pakistan, where self-awareness of porters is much better articulated than in Nepal (and where pay scales are about ten times higher), collective bargaining is absent. According to Kenneth MacDonald, a University of Toronto researcher, “There are no unions or association of porters among the Balti, as collective identity stems from the village and kinships, rather than from the occupation.”

While, trekking might see some collective bargaining before long, this is not even a remote possibility in commercial portering, which involves the heaviest loads and many times the number of porters engaged. No government agency or NGO has yet stepped forward as an advocate for the inhumanely exploited commercial porter.

From Dehydration to Hypothermia

The myth is that only plainsmen and tourists get acute mountain sickness. Not true, says Dr. Buddha Basnet, Medical Director of the Himalayan Rescue Association (HRA). Dr. Basnet says midhill porters venturing up the high valleys are equally susceptible. He says, “The worst cases of altitude sickness – full blown pulmonary or cerebral edema-brought down to HRA’s posts tend to be trekking staff.”

By and large, hill porters are unprepared for the demands of high altitude travel. Encountering the unique terrain of high himals, they become disoriented and often suffer psychological stress. Symptoms of AMS are dismissed as boksi lagyo, which means witch’s curse. Untreated bruises, lacerations and abrasions that are part and parcel of load-carrying, lead to frequent infections. Porters suffer from hypothermia, caused by exposure to the elements without warm clothing, while, they are also victimised by dehydration from drinking contaminated stream water and eating unhygienically on the trail.

“Even at high altitude, trekking is a ‘hot weather activity.’ Heat is as much a problem as cold, and it is important to get the message across to the porters that they must drink plenty of fluid replacement,” says Dr. John Dickenson, a pioneer of trekking medicine. There are places where the porter must be encouraged to carry a water canteen, even if this means adding to his load.

According to studies cited by Dr. Basnet, high Himalayan populations such as Sherpas, seem to enjoy physiological advantages over their midhill counterparts. As part of evolutionary adaptation, for example, Sherpas seem to have higher oxygen levels in their blood stream because they breathe (‘ventilate’) more. Thigh muscle biopsies of Bhotiya populations show that they have a higher capillaries-to-fiber ratio than hill people. They also have less pulmonary artery constriction at high altitude than hill porters, who are therefore, more prone to waterlogged lungs (pulmonary edema).

When a dhakrey stops his heaving and halts to catch his breath, is he following a cardio-vascular dictate or is he stopping to relieve pain? This is a question that researchers have yet to study, but the porter has other things on his mind… When University of Colorado scholar Nancy Malville asked a Rai porter on the Jiri trail, “Where does it hurt most?” the quick reply was: “At the Lamjura Pass!”

Load and Body Mass

East African women typically carry loads equivalent to about 70 percent of their body mass (about 40 kg), and the heaviest baggage carried elsewhere, using a tumpline, seem to have been by the Canadian voyageurs, who transported heavy loads for short distances, while portaging their canoes and goods from one lake to another. The average load carried by the voyageur, whose days are long past, was 80 kg.

Only in Nepal, does the porter’s toil continue. Unlike other load carriers, and even Olympic weight-lifters, the bhariya’s exertion is sustained over days on end. The porter trail studied by Nancy Malville, which leads from the Jiri roadhead eastward to Namche, takes ten days of continuous carriage for a fully laden dhakrey. He returns in four days, to repeat the cycle. His total elevation gain over the route is 21,000 ft and total loss 16,500 ft.

Nancy Malville, assisted by her astronomer husband Kim, focussed her inquiry on the relationship between the porter’s body mass and his load. She found that youngest porters (11-15 years) carried an equivalent of 135 percent of their body mass, and men in their sixties were still hauling goods of up to 60 kg or, 116 percent of their body mass.

Males in their late 20s carried the heaviest loads, 83 kg (182 lbs), in relation to their own size, equivalent to 159 percent of body mass. The heaviest load encountered was 108 kg (238 lbs), carried by a 44-year-old Rai trader, Bhim Bahadur Sunwar, who stood 146 cm tall (4’9”) and weighed a mere 47 kg (104 lbs). Bhim Bahadur was carrying 228 percent of his own body mass.

Malville also reported that, overall, the heaviest loads (an average 160 percent of body weight) are carried by dokay sahus, merchant-porters who seek profit for themselves and hence, have the strongest motivation. Porters hired by shopkeepers were routinely carrying 145 percent, while those doing ‘self-portering,’ i.e. carrying goads for their own households, heaved the equivalent of their own body mass. “The normal value for non-commercial load carrying in rural Nepal seems to be 80 percent of body mass,” says Nancy Malville.

Clearly, the Nepali porter would win the gold in any Olympic competition, if the criterion were load-to-body mass and endurance. While beefy weight-lifters can hoist carry heavier weights, they do not carry twice their own body mass. As Kim Malville says, “It is important to note that weight-lifters lift, and that, too, momentarily, but they do not transport!”

Rotors vs. Porters

The political and economic collapse of the Soviet Union has had a direct and reverberating impact on Nepali porters, for it made helicopters available to the Third World at cheap prices.

Over the last two years, Russian-made Kazan Mil7 helicopters, with the ability to lift up to four tons from a runway and three tons vertically, have devastated the portering market of the eastern Nepal hills. As the thudding rotors ferry food grains, construction goods and development material to far-flung outposts, whole villages lose their only source of cash income, down below.

Technology and the market, when they work together become an unbeatable combination, and perhaps, going back may indeed be retrograde. However, in Nepal there has not even been the semblance of a debate, as the copters wrest away livelihoods of thousands. The loud members of the Nepali Sansad’s government and opposition benches, have not found the need to address this issue, although, it is subject for both the socialists of the Nepali Congress and the communists of the United Marxist Leninists.

What is the solution to this gruelling occupation, if it is not to be helicopters? The one cautionary note that Dibya Gurung and Tsering Tenpa made in their paper on “Women as Porters,” is that there should be no misplaced charity. Just because porters’ issues are being highlighted, it does not mean that a simplistic solution be sought to abolish portering by fiat. The is a job that women and men have taken up because of economic necessity, they say, and the supposedly demeaning act of “carrying another’s load” is academic as far as the porters are concerned. The focus, instead, should be to search for the interest of the porter – female, male and child – while generally working to develop the socio-economic status of the hinterland hill population.

There is no interim panacea to genuine development of the country, taken as a whole, with the hills near and far taken along with prosperous Kathmandu Valley and the tarai. The moment the peasant has work that provides an alternate source of income, he will stop portering. Says Anil Chitrakar: “Portering is the starkest symbol of failed development after four decades of trying. Only when we have succeeded in removing the namlo from the thaplo, can we sit back satisfied that bikas has arrived in Nepal.”

Until that time comes, we can, at the very least, notice the porter’s burden the next time we pass him on the trail. Says Pitamber Sharma, “The sweat the porter expends is in the hope for a better tomorrow for his progeny. For his efforts, the Nepali porter is a hero. He deserves the respect that is his due.”

Himal plans to publish in a paperback the proceedings of “Hard Livelihood: Conference on Himalayan Portering.”

Namlo for Spondylosis

Upendra Devkota, Kathmandu-based neurosurgeon, presented preliminary results of a study on the upper (cervical) spine of the male Nepali porter, stating that he had found significantly less degeneration than expected. Spondylosis is the wear and tear of the cervical spine that comes with age, and it would seem that a porter’s neck would be more susceptible than others’. “There was reason to expect that there would be accelerated degeneration, but these preliminary results indicate otherwise,” says Dr. Devkota, who expects to present conclusive findings after further research. “The porters seem to have significantly better necks compared to sedentary populations.”

In the age group 40-49, among the 49 commercial porters studied, 12.2 per cent showed signs of spondylosis, whereas 25 percent would have been normal according to medical literature. “This tends to suggest that male Nepali porters in their 40s have significantly less spinal degeneration compared to their Western controls.” If his preliminary findings are confirmed, then the namlo tumpline should be the suggested physiotherapy aid for spondylosis patients.

Stress and Recovery on the Trail

By Nancy Malville

Heart-rate monitoring of commercial porters conducted in August 1995 demonstrated the importance of the tokma to the technique of carrying very heavy loads over long distances. The tokma is the sturdy T-shaped walking stick used by commercial porters in eastern Nepal, to provide temporary support under the doko basket during frequent rest stops along the trail. The heart rate plot shown here, that recorded 5-second intervals, presents a typical heart rate pattern of a commercial porter walking uphill. In this case, the porter is a 33-year old Magar walking up the Kenje hill carrying a 87-kg load (169 per cent of body weight). While walking uphill, this porter stops every 135 seconds, on average, and rests for 60 seconds, placing his tokma under his doko and removing the namlo from his foreheads, as he rests. During the brief rest stop, the heart rate decreases quickly by 30 to 50 beats per minute, then increases again as soon as the porter resume walking. After walking for half an hour, the porter sets his load on a chautara (rest platform) along the trail and relaxes for 10-12 minutes, during which his heart rate drops to the initial level recorded during interview session in Kenje. This technique of intermittent stress and recovery enables the porter to pace his exertions throughout the 10-day journey from Jiri to Namche.

On Balti Notoriety

By Ken MacDonald

The words used to typify the Balti porter in travel, exploration and mountaineering literature include garrulous, belligerent, greedy, unreliable and cowardly. Regardless of the individual experiences that generate this image, the power system that sustains and extends it has produced a stereotype of Balti porters, as unreliable.

I would suggest that the acts that have led people to label Balti people as unreliable, cowardly and so on are actually acts of resistance carried out in an effort to exercise a degree of self-determination, and retain an element of dignity in a task that can be most degrading. What has been transmitted among travelers as a bad reputation is actually, a racist misinterpretation of the actions of a subordinate group, involved in continuous resistance against domination and the appropriation of their labour.

Women as Porters

By Dibya Gurung and Tsering Tenpa

Portering as a money-earning proposition presents to women an escape from the drudgery of their village existence, their continuous unpaid labour, and their poverty. These apparent gains – hard cash, freedom, exposure and new confidence – are what portering can give them. And in reality, they have no other option, as no employment comes their way. Under these circumstances, they should be encouraged, especially, since they have proved themselves capable of the labour required.

For women in the occupation, therefore, portering is an employment opportunity which they do not want jeopardised by well-meaning activists. Any action on their behalf must be taken only with careful forethought and sensitivity. However hard the life of women porters may be, it is one that they have chosen because they had no other alternative. But that does not mean that we should stop after telling the story…

Dead Porters Don’t Protest

By Ramyata Limbu

The freak storm that hit the Nepal Himalaya from the 9th to 10th earlier November saw prompt helicopter evacuation on an unprecedented scale coordinated by a government-tourism industry task force. It was a well-reported, commendable job. However, while reports are sketchy, it seems clear that porters, forming the lowest strata of the trekking trade, were neglected in the rescue operation.

Altogether 549 people were airlifted out of the mountains, of which 250 were foreigners and 299 Nepalis. It is a ratio of almost one-to-one, which itself indicates that something is amiss. On the average, the client-to-porter ratio for organised treks in the high Himalaya is 1:4, which means that many more porters must have been left stranded or dead on the mountain than were air lifted out.

The fact that the number of Nepalis reported dead is almost twice that of foreigners is similarly illuminating. The government’s figure on whose bodies have been found is 22 foreigners and 42 Nepalis. The Trekking Worker’s Association of Nepal (TWAN) claims that many more Nepalis have died.

While the foreigners are normally well-equipped for eventualities up on the mountain, Nepali porters do their jobs with the hope that the weather will stay friendly while going over the pass. Only a handful of the more expensive trekking agencies are known to provide porters with the minimum required clothing and gear.

Inadequate clothing and equipment is the main reason so many Nepalis succumbed to killer storm, says Padam Singh Ghale of Mandala Trekking. At one point, there were said to be fifty porters suffering from snow blindness registered at the Kunde Hospital above Namche Bazaar.

TWAN officers are indignant that their group was kept out of the task force, and that they were unable to board helicopters to ensure that porters were not neglected by the rescue efforts. They also claim that there was discrimination in identifying and bringing back the dead.

This information is mostly anecdotal, but rings true. Dead bodies of foreigners were put into wooden boxes, while Nepalis were slipped into sacks. Initially, only the bodies of foreigners were brought to Kathmandu while the Nepali dead were said to have been dumped into rivers. “I’ve heard similar reports,” says Ang Gyaltsen Sherpa, Trekking Director for Trans-Himalayan Tours, a group that lost 13 Japanese tourists and 10 Nepali staff in the disaster. “Most probably it would be Nepali porters whose bodies are being thrown away.”

In the Kanchenjunga region, it is said, a helicopter landed and took off without taking anyone, with the pilot saying, “There are only Nepalis here.” Elsewhere, the going rate of helicopter evacuation was said to be U$ 400 for the eight minute flight from the Gokyo to Pangboche in Khumbu, and U$ 200 equivalent for Nepalis.

The government has stopped counting bodies, and the trekking industry is almost back to business as usual. No one knows how many bodies of Nepali midhill porters strew the mountain passes, as most trekking agencies find it convenient not to report their dead. All across the middle hill, however, there will be men (and some women) who will never return to the homestead.

No one will be counting, either, when the spring thaw most likely reveals bodies all across the high passes of Nepal.