From Himal Southasian, Volume 14, Number 7 (JUL 2001)

The royal palace killings marked a cultural watershed for the people of Nepal, the security of the past shattered and an uncertain future left to negotiate. Yes, a son can kill his father, mother, and more. Yes, assault rifles can fire many bullets per second. Yes, there are no illusions left. But after the shock, confusion and smouldering ashes of Arya Ghat, there is still parliamentary democracy. What remains of Nepal’s royal family may descend from its perch and inject energy into the life of an unguided nation. The new man at Narayanhiti may have the sagacity to remain constitutional monarch in a country going rapidly extraconstitutional. The post-Panchayat penance for past authoritarianism is over, and Nepali kingship must now work openly with government and Parliament to bring peace to a shattered land.

Nepal is robust enough a country to carry on without a king. This was proven when it switched from absolute monarchy to multiparty democracy in 1990 and failed to collapse, contrary to three decades of Panchayat-period propaganda. The point was confirmed over the last 11 years of democratic misrule when, abused by the parties and politicians, the country remained on its feet.

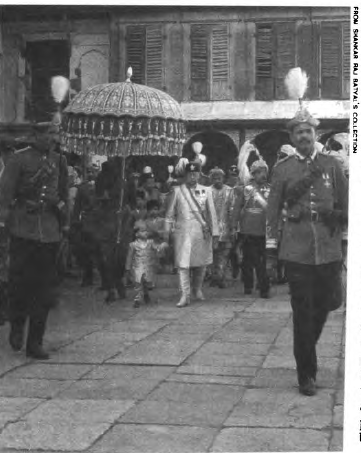

On the other hand, Nepal is fortunate to have a king, as a fulcrum of national identity and institution of last resort. This is a privilege not available to the people of the other larger South Asian countries, whose ‘natural’ historical evolution was interrupted by the colonial interlude. Rather than a republican presidency, Nepalis have a kingship that reaches back to the very creation of their nation-state two and a half centuries ago and actually much further. That is comforting, except • for those who have no use for tradition. Unique in South Asia, over the decade of the 1990s and up to the present, Nepal has been experimenting with a mix of late-model Westminster democracy backed by an ancient monarchy with its own rituals, paraphernalia and modus operandi. In the midst of this try out, on the night of 1 June 2001, the society was visited by the most violent tremor imaginable. But despite the Guinness-book proportions of the tragedy within Narayanhiti Royal Palace, not one institution of state faltered even as insurgents stood ready in the hills to take advantage of this sudden crumbling of the most secure institution of state. While the ‘handling’ of the crisis has been roundly criticised, the fact is that two royal successions were managed amidst the crisis, and the shock and anger of a bereaved and unbelieving public controlled.

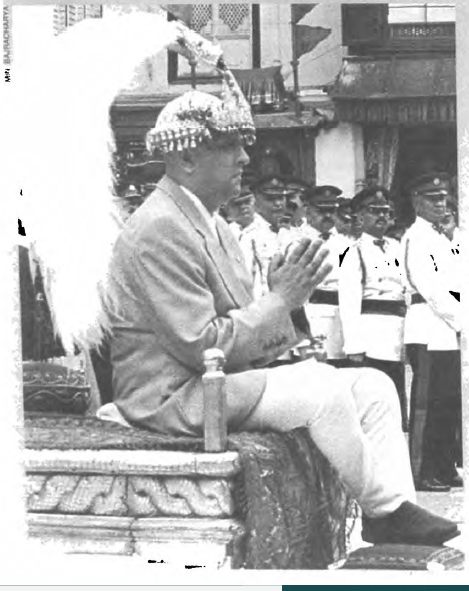

Indeed, a critical breakdown might well have overtaken the state following that dark and cloudy night, when a little after nine, King Birendra was murdered and his branch of the Shah dynasty wiped out to the last soul. But Nepal actually weathered this decimation of the monarchy despite the mass bewilderment and public angst. And now, all eyes are on Gyanendra, who has just had the plumed crown thrust on him. Can the new king dig himself out of what at its core is a family tragedy, and establish himself quickly as a constitutional king who can work with government, Parliament and civil society? Can he help bring back peace and a sense of security to a country of multi-hued minorities?

The Nepali kingship has long been transformed into a constitutional entity from its earlier authoritarian garb, and much of the precedents are already in place, the legacy of the just-departed king. However, Birendra was a laid back and retiring monarch, who preferred not to explore the envelope within which to function. King Gyanendra, on the other hand, will have to be progressive and dynamic, a democrat king to join in on the rescue of the parliamentary system and its possibilities.

The political parties and intelligentsia will be on high alert against royal adventurism and attempts at consolidation of power within Narayanhiti, and they remember well the royal takeover by King Mahendra, whose dour and decisive personality his middle son has inherited. King Gyanendra will have to cross this shoal of suspicion, with a transparent and personally unambitious agenda. The three decades of authoritarian monarchy was a failed experiment, and as modern king of a messed-up country, all Gyanendra can do is to support the parliamentarians and politicians to make this Westminster-by-the-Bagmati democracy function.

Bonfire of conspiracies

Politically, Birendra’s passing was the loss of a personality who represented change and continuity. He inherited the Panchayat system and ruled as absolute monarch for 18 years, after which he reigned as constitutional king for another 12. Reviled by the urban middle class during the end-run of the Panchayat in the 1980s, Birendra subsequently claimed his place in the public heart by remaining resolutely constitutional over the 1990s. With the shenanigans of the commoner party politicians holding centre-stage over the last decade, the palace receded from national glare and the king was transformed into an avuncular and inactive icon. Crown Prince Dipendra’s public debut as an enthusiastic patron during the South Asian Federation Games of Autumn 1999 therefore came as a pleasant surprise to a public that wanted more eye-contact.

While King Birendra retreated into the palace after conceding power to the people and Parliament, for a decade, Nepal had continued to sink ever-deeper into the abyss of bad governance. With factional fighting within political parties, street-level agitation by the opposition in lieu of parliamentary debates, buy-offs of parliamentarians, police terror in regions remote from the capital, national strikes and countrywide school closures, an economy in ever-greater tailspin, and a Maoist wildfire through the midhills—by the early summer of 2001 it was as if nothing more inauspicious could visit this society.

But within the walls of the royal palace, a family quarrel was brewing, a developing tension that the public was completely unaware of. Unknown to all but the exclusive circle around the royals, Crown Prince Dipendra was a violence-prone, emotional volcano about to erupt. Given to drink and hallucinogens, Dipendra was battling a headstrong mother and family who used every argument from the astrological to the requirements of lineal purity to keep him from wedding his chosen partner. Further, there was the spectre of having his royal status and right of succession revoked if he went his own way, and Dipendra was also confronted with the imminent betrothal of his younger brother Nirajan. And not so incidentally, as a lover of weaponry the crown prince was evaluating a run of the latest assault rifles for the army, where he came after the king in line-of-respect as ‘Colonel-in-Chief. He kept a rack-full of sophisticated automatic arms on the ready in his bed chamber at Narayanhiti.

Such was the background to the night of 1 June when the crown prince’s mind appears to have snapped. In no more than a few minutes of real time, he had descended from his room in combat attire, toting four automatic weapons, and pumped bullets into his father, mother, sister, brother, aunts and uncles, earning for himself a place in the most macabre list of death-dealers in world history.

A traumatised public refused to believe the bizarre information that leaked out over the first few hours and days, confirmed two weeks later by a high-powered investigation team appointed by Gyanendra. With the survivors of the carnage having spoken, and evidence from the bloody palace precincts collected, the finger pointed beyond all reasonable doubt at Dipendra. The public’s emotional rejection was explained by the Paras Shah bad-boy factor (Gyanendra’s son, involved in road deaths that had gone unchallenged earlier due to palace pressure), and the fact that Gyanendra’s immediate family survived (although the new queen, Komal, survived after a bullet missed her heart by centimetres, and there were 14 family members who survived to the 10 who died). The intelligentsia’s reaction was also governed by Gyanendra’s reputation as a Panchayatera hardliner, which led imaginative minds to jump to the conclusion that Gyanendra (away in Pokhara inspecting some development projects) must have master- minded an intricate assassination scenario and palace coup.

The investigation committee set up by King Gyanendra and headed by the Chief Justice Keshav Prasad Upadhaya took a little over a week to produce a detailed report, visiting the site of the killing, collecting primary evidence, and recording statements from the royals, guards and retainers. Despite the tension-ridden times, that committee did a commendable and dignified job with its report — except for the buffoonery of its other member, House Speaker Taranath Rana Bhatt, at the report’s unveiling press conference. The mass of material resulting from the committee’s work, including videotapes and photographs, will take a long time to unravel, but for those willing to wade through its 220-page report the conclusion was clear even if not spelt out as an indictment.

The sheer magnitude of what Dipendra had done, the inability to comprehend the rapid-fire destructiveness of automatic weapons, the confusion and lack of information in the initial days with a royal palace reduced to counting corpses, and the people’s distanced impression of Dipendra as a cherubic and affable crown prince, all added fuel to the bonfire of conspiracies. The chasm between the elite royalty and the commoner intelligentsia, which would otherwise have mediated between the event and a disbelieving public, also played a part in the inability—and refusal—to reconcile with what seemed to have happened. The near-total lack of faith had also to do with the sources of information being exclusively royal or military, with the civilian politicians completely out of the loop during those first few days of tragedy. Even till date, Dipendra’s motivation remains a matter of conjecture, with little detail emerging from the surviving royals regarding the crown prince’s romance and its stonewalling by King Birendra and Queen Aishwarya, his alleged violent nature, and his passion for gunnery.

For the sake of the legitimacy of his succession, the new king will have to take the people into full confidence about the tragedy. Distasteful events related to Kathmandu royalty have historically been swept under the feudal carpet, with society having to move along with a less-than-complete version of events. This cannot be so in the present age, nor is it in the interest of the country. The Parliament—in session currently—the government and the royal palace must together move beyond the report of the investigation committee, going further into the evidence, and seeking answers to the question of motivation. This may require delving into interpersonal relationships within King Birendra’s family and exploring the crown prince’s psychological profile as well as his relationship(s).

These are issues to be dealt with professionally, under parliamentary supervision, rather than at the hands of local journalists, foreign parachutists or hagiographers. Only complete information about the terrible night and its familial backdrop will inform the public and help it to accept the truth. Trust is an asset for a constitutional modern-day king, unlike the autocratic monarch who can rule by the sword and extract obeisance. The Nepali kingship can and should be salvaged at this time, when the other lofty institutions— the political parties, the courts, the bureaucracy, the army and police, and Parliament itself—are still in need of its potent presence.

The country would enter a bottomless pit of recrimination and suspicion if the royal palace murders were indeed part of a plan, a coup, a conspiracy—if King Gyanendra had sought the bejewelled Bird of Paradise crown. If that were the case, the country and people might as well have done away with the institution of tainted monarchy in one stroke. Fortunately, the reality is clearly otherwise and only needs reconfirming. The people’s acceptance that King Birendra was murdered and not assassinated must be based on conviction rather than a fatalistic acceptance of fait accompli, for that would never allow for full healing of the national psyche and would surely lead to the hastened demise of the House of Gorkha.

Form and content

Given that the unthinkable has happened, the Narayanhiti tragedy will best be used as a splash of cold water on the nation’s face, to make all vanguards of society in politics, academia, business and social activism sit up and re-commit themselves to a country and political system whose promises have long been wasted. If the tragedy shakes up the educated classes enough that they will begin to distinguish the form of parliamentary democracy from its necessary content, and define their thoughts and activities accordingly, this will have given some meaning to the senseless carnage at Narayanhiti.

The jolt of 1 June having taken the country so close to the brink, the political parties may henceforth be more circumspect and principled, basing their programmes and inter- and intra-party relationships on ideals rather than on personal and factional ambition. Since each and every matter relating to governance is defined by the manner of politics at the top, if the process is set right there will be improvement right down the line, in bureaucracy, planning, development, and the economic, social and cultural spheres.

The reason the politicians—as well as Kathmandu’s ‘civil society’ and the intelligentsia—have been negligent of the prize of democracy is that it was had rather easily. It was a case of immediate gratification when, in 1990, King Birendra relinquished his absolute monarchy in response to a ‘movement’ rather than ‘revolution’. With little intellectual exposure, inadequate political grooming and quick rise to prominence, the politicians in government and in opposition quickly descended to corruption on the one hand and factional bickering on the other. While their low level of commitment to the parliamentary system was becoming increasingly evident over the years, it was confirmed by the fact that the political groupings did not come together even when the insurgent Maoists declared violent war on the state and system, and moved quickly to establish their presence in large parts of the country.

People do not get the government they deserve. They get the government the middle class thinks it deserves. In the case of Nepal, it is not the masses in the hinterland but the educated classes of Kathmandu Valley that gives the spin to national politics. If the answer to today’s doldrums is a qualitatively higher level of political discourse, then it is the responsibility of the Valley’s political consumers to extract better performance from the parties. Unless there is a secret authoritarian fixation in this class, unless beneath the professed commitment to pluralism lurks a supine desire for authoritarian rule—either monarchial or Maoists—it is time this class organised to hold the politicians to their promises. Even though the Narayanhiti massacre was an in-house manslaughter rather than a political event in its origin, it could still serve as shock therapy — if it disturbs the country’s political and middle classes enough to emerge from their insularity

Historical bonus

There is nothing inherently wrong in seeking a republican government with a president chosen from the people, but why not use a monarchy when it is available? For a traditional society barely coming out of the age of feudalism, a parliamentary system backed by a constitutional king kept firmly in his place by a watchful intelligentsia is bound to be more useful than a presidency. A kingship, after all, is a bonus available only to countries that have been allowed a continuous history. Doing away with it would be an act of monumental foolishness, one that Crown Prince Dipendra nearly completed for his own reasons. Incidentally, one would have thought that the Maoists would be happy with this weakening of monarchy, but even they have let on their posthumous admiration for the late Birendra and, verily, for the nationalist streak they claim to detect in the Shah dynasty as a whole. As present king, Gyanendra, is exempted from this run of adulation, however, being identified by the Maoists as nothing more than an Indo-imperialist plant.

Minister Girija Prasad Koirala,14 June.

While mourning the loss of King Birendra, Kathmandu’s educated may want to consider how fortunate it is that the dynasty of King Prithvinarayan Shah was not entirely decimated on 1 June, and that there was the lone brother left surviving amidst the fallen. The social cohesion and cultural direction that a wise and astute monarch can provide should not be underestimated, and the symbolism of kingship will of course continue to favour a whole variety of national activities, from the rituals of state and community to cultural activities in a myriad of spheres. From providing a focus for the country’s disparate communities in a manner that the politicians will not be able to for some time to come, to serving as an extraordinarily exotic icon for an economy that relies overwhelmingly on tourism, there is no argument about kingships’s utility for Nepal.

A constitutional king need not be a passive king, and today the country requires a proactive institution, a facilitator and a mediator in the social, cultural, economic, and even political, arena. It is a role that King Birendra had, by personality and circumstance, not been willing to take on. Working with community leaders, scholars and social scientists, King Gyanendra will have to try to and understand the excruciating time that is the Nepali present, and use his privileged position to nudge and push the society and economy forward.

It cannot be a pleasant experience to be anointed king of a country as materially deprived as Nepal. The rural majority remains shackled in poverty, except that unlike in the past, today it observes the conspicuous consumption of old money and nouveau riche in the Valley. The political system is democratic in form, but not yet pluralistic in content, with the ethnic groups of the hills, dalits all over, and the people of tarai origin feeling distanced from decision-making. Meanwhile, the headlong rush to consumerist modernity among the middle class is being accompanied by the abandonment of any and all cultural moorings. Joint families are being torn asunder, highways tear up the rural fabric, and foreign satellite television has taken monopoly control of young minds. Age-old traditions, of which Nepal has till this late date been such a proud repository, are being lost in the twinkling of an eye without anything indigenously modern to take their place. Teachers are as lost as the parents, so the youth are without bearing epitomised in the extreme act of Dipendra’s psychopathic desperation.

The country is bounding into the modern era with wholly inadequate leadership from the political classes, the cultural elite or the intelligentsia. Look around, and there is hardly a religious or spiritual leader to guide the flock and provide it with cultural perspective — so much so that King Birendra, reincarnated Vishnu to some, died with a Sai Baba locket on his chest. Everywhere, in the mandirs and gombas, the form of ritualism crowds out the content of philosophy.

In countries that suffered colonisation, the national economic and administrative elites that emerged have at least served as a cushion during the transition to modernity. Nepal, on the other hand, is leaping from feudal to globalised times without facilitation. As a king who commands at least some of the ab initio respect that others have to strive to earn, King Gyanendra can try his hand at pouring cultural balm over troubled waters. He comes to the serpent-backed throne as a mature and worldly 54-year-old, after all, and not as a young adult in thrall of his new seat. If he has the public relations skills and the ability to work with the political, cultural, social and economic leadership, Gyanendra might just be able to join in the task of healing the shattered national psyche and redirecting and energising the collective imagination.

encounter with the crown.

The disadvantage of kingship is that the public cannot choose its man. But if King Gyanendra understands the moment, then he will certainly discern what kind of king the people need at this hour. From being the aloof and occasionally controversial younger brother of King Birendra, he must emerge as caring, empathetic, proactive— yet simultaneously unambitious. He must descend from the royal pedestal and act as catalyst and actor in the critical areas requiring his presence and patronage.

King’s new clothes

Once anointed as monarch for a few months when but a four-year-old in 1950, put there by a Rana regime near collapse after the rest of his family had fled to New Delhi, Gyanendra lost his over-sized crown when grandfather Tribhuvan returned to take over. The onetime infant king watched his father Mahendra’s and then his older brother’s coronation. As the once-again king, in late middle-age, Gyanendra is required now to reorient his family life and professional commitments to respond to a new setting. Beyond the questions of perceived legitimacy of his succession, he will have to tackle several personal matters to the satisfaction of the public, including the ‘Paras factor’, the settlement of his business holdings, and the question of opening up the royal household to public scrutiny and ownership.

As prince till a month ago, Gyanendra was someone with extensive business interests ranging from tea gardens to tourism. In the social sector, he was also engaged in organisations involved with cultural and environmental conservation, and community development. The Soaltee Group, through which Gyanendra holds shares together with many of the recently deceased royals, is by far the most ‘corporate’ among Nepal’s business houses, with collaborations with bluechip international companies and providing a hefty chunk of the taxes received by the national exchequer. While the holding company itself is in the hands of professional managers, for one who is regarded as a can-do person, the new king’s involvement in the Lumbini Development Trust was not able to lift the Buddha’s birthplace to become a spiritual centre, other than saddling it with an eternal flame that has to be fed — eternally. As prince, Gyanendra’s main public task was running the King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation, an organisation which carried out most of its innovations during the Panchayat period and floundered in the last decade.

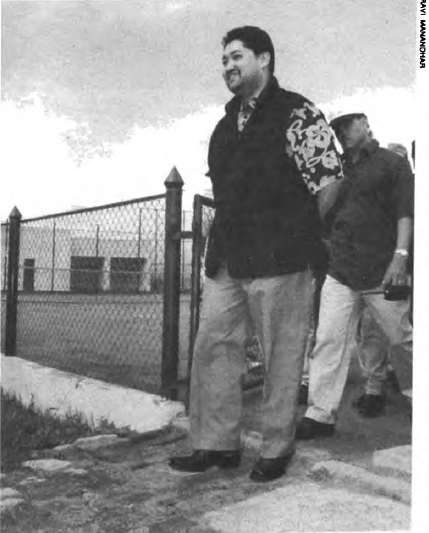

Besides being suspicious of Gyanendra’s income generation efforts in the past, including money earned under the privilege of non-competion, the urban middle class, at least, looks at the new king askance for his alleged hardline views during the Panchayat period— no matter that he seemed to stand silently behind his brother during the latter’s years as constitutional king. But, most of all, the public is angered by Gyanendra’s indulgence towards his wayward son, Paras Shah. This was, in fact, the primary cause for the rampant rejection that greeted his fledgling kingship in early June and there may well come a situation where the monarch will have to choose between the people and his son. However, this is not a question that needs an urgent solution, as long as the young man is not declared heir and crown prince in haste. It is fair to say that, if the son factor is neutralised for the time being, King Gyanendra will receive the space he needs from the people to start working on their behalf.

Rather than staying with the trappings of ritual and tradition, and remote within the walls of Narayanhiti, the king of Nepal must now bring royalty to the people and do away with the aloof identity that it cultivated ever since King Mahendra went all serious behind dark glasses in the early 1960s. Transparency rather than distance should define the royalty’s new relationship with the people, responding to the need of the times as well as to protect it from charges of power-mongering. As far as the royal children and cousins are concerned, most of them young and hopefully still capable of grooming, King Gyanendra can ensure their evolution as socially-oriented scions rather than the disco-thumping, smoking-sniffing bratpack that Crown Prince Dipendra and Paras Shah apparently preferred to move with. Without such an effort, the people may not be willing to stay with kingship at the time Gyanendra’s reign comes to an end.

The setting up of the inquiry committee into the massacre was the necessary first step — albeit dictated by circumstances — to opening the portals of the royal palace. The decision by King Gyanendra, on the very day he donned the crown, to allow the committee to have the run of Narayanhiti and its denizens was a landmark beginning, which must now be extended to bring the royal palace’s affairs more within the purview of government and Parliament.

Openness and transparency of the royal palace are not ends in themselves, however. This proximity is to be used to provide cultural energy to a country beset with problems, and no political party could deny King Gyanendra a role if he decides to actively pursue an agenda to improve, say, the country’s education system or its abysmal health care. Indeed, if King Gyanendra wanted to leave a legacy, it could be through a single-minded devotion to improving Nepal’s school and college education, a sector that his brother Birendra was responsible for initially damaging in the early 1970s in a misguided effort to ‘modernise’ it. It is clearly the terrible lack of learning opportunities, over decades of trying under both absolute monarchy and parliamentary democracy, that has brought the country to its knees today, and which explains the society’s precipitous fall in nearly every sphere.

Beyond education, King Gyanendra will find a host of issues that can engage him till the end of what will hopefully be, as they have already started saying, “a long and glorious reign”. Because the country has been so thoroughly mismanaged under both autocracy and democracy, he will find the door wide open for royal proactivism in a variety of arena — from tackling the country’s shocking child and maternal mortality rates to trying to preserving Kathmandu Valley’s cultural heritage; from lobbying for better representation for Nepal’s minorities in politics and administration to wildlife conservation and alternative energy; from pushing the business sector to make better use of Nepal’s comparative advantage vis-à-vis both the Indian plains and Tibetan plateau, to addressing a wide range of social problems such as trafficking in women, drug addiction, child labour, and all kinds of new-found psychological distress among the populace.

To be part of the agenda of social reform, King Gyanendra will need research and analysis of the kind that the feudocrats in the royal palace’s secretariat can hardly provide. In fact, that office even today projects the image of faceless yes-men who help to distribute royal patronage, obfuscate issues on behalf of royalty, and play the occasional mischief with political parties. Gyanendra’s palace office will have to shed such an image and role, and transform into a responsive institution open to criticism, and one which relies on social science to study the challenges facing the people and landscape. Such a royal palace would complement and back up the work by the government, the non-governmental organisations, as well as academia.

Monarch as democrat

The constitutional track is non-negotiable and already largely defined, and the new king himself was quick to confirm his fealty to the 1990 Constitution in his first address to the nation the day he was crowned, on 4 June. But an activist constitutional monarch need not be a contradictory notion, and it is a road that can be taken as long as King Gyanendra understands that his role, above everything else, is to support democracy through Parliament—not to try and amass power around the palace and its hangers-on, to play parties against each other, or to create the straw figure of extreme nationalism to cushion his own throne. This was what Gyanendra’s late father, the mentally agile and ambitious Mahendra did as prelude to wresting power from the elected government of B.P. Koirala in the royal coup of December 1960. (A re-reading of history will serve to sensitise both the royal palace and political classes on what kind of monarchical activism to watch out for, and to desist from, in the days ahead. On the other hand, the new king’s transparency may finally help rid the Nepali mind of its 1960-fixation and allow the monarchy to get closer to the people.)

Kathmandu’s civil society organisations can be expected to be on guard to prevent any slippage into authoritarianism, and there is also no doubt that King Gyanendra will pick up controversies as soon as he comes out of the period of mourning and begins, as expected, to take an interest in the national issues awaiting resolution. But this fear of backlash should not pre– vent him from trying to make Nepali monarchy relevant to modern times, even while the king steers clear of even the perception of playing power politics with regard to matters such as the balance of strength in Parliament, secretive deals with political groups, or using the army as its own. King Gyanendra will know that if there is one issue that will unite the forever bickering political parties of his kingdom, it will be the threat of a power-hungry kingship.

An insular, feudally-oriented royal palace will not have the dynamism to chart the choppy waters up ahead, but there is no doubt that a dynamic monarchy openly dedicated to parliamentary democracy would be a boon, including as an honest broker between the various social and political forces. If King Gyanendra can shed the distanced airs of his predecessors and command the respect of the public, he may even be able to lift the political parties to a higher threshold of principles. Factionalism within each political group and the displacement of professed party programme by personal agenda lie at the core of the rot that is ripping the fabric of Nepali democracy. As an institution with clout and prestige, the monarchy can work to curb this disease.

The new royal palace should also plan to clear the murk that pervades the role and position of Nepal’s army. While the general principle is clear, that the military must remain under the full control of a duly-elected executive, in reality the powerful but untested military of Nepal sees its loyalty lying with the king. The army brass has extreme distaste for the political parties, partly for fear of being politicised and corrupted by the politicians— as happened with the police force — but also because of the historically incestuous linkage between royalty and the military. Recognising the situation, King Gyanendra will have to help Parliament prepare the ground in which the army’s authority is unequivocally transferred to civilian authority. A good place to begin re-evaluating the army’s place in the national firmament will be to study the lapses in the security that led to the death of its patron and Supreme Commander on the night of 1 June.

The overwhelming issue confronting the population, one that remains in place like a dark shroud even as the burning pyres of King Birendra and his family recede in memory, is the ever-present and expanding Maoist challenge to the Nepali state. If the mainstream parties are unable to sink their differences and identify a common platform to confront the Maoists with, then King Gyanendra may be forgiven if he tries his hand at a resolution. If others do not have the standing or the inclination, the king can make an open call for dialogue and see whether the parties will not rise above tactical and factional considerations to consider the Maoists’ challenge. Rather than a fight to the finish using the unleashed firepower of the army, it has become urgent to seek ways to coax the Maoists to cash in their underground chips for above-ground political power. A strong government and a believable interlocutor are what have been lacking in trying to bring the insurgents to the table. The king of Nepal, who is also a Nepali citizen, will not be grudged the space if takes the initiative.

Monarchs are, after all, individual human beings. Good and bad kingships are defined, more than I anything else, by the personality, style, likes and dislikes of the person who ascends the throne. One constitutional monarch may want to lean back and let matters take their course, and another may like engaging with the issues. Of which mould will Gyanendra be, and is he sufficiently agile to function amidst the combative political landscape if it is to be the latter? Above all, will he have the forbearance to return to the royal palace as and when the brushfires are put out?

When the dust and ash have finally settled on the royal massacre, and as the public begins to learn to live with him, King Gyanendra will find that his plate is full as head of state of 23 million Nepalis. To communicate with them, the new king of Nepal must learn to speak extemporaneously, express opinions in open fora, and try and maintain eye contact. Times have changed, as have expectations.

As for the members of Kathmandu’s still-unbelieving intelligentsia, they may want to consider one final point. From what we know till now, what if it was Dipendra rather than Gyanendra that had become king?