From Himal Southasian, Volume 18, Number 1 (JUL-AUG 2005)

Will peace in our times be achieved because methane from Iran is allowed to enter India via Pakistan? Is it as simple as that? It is beginning to look as if it is.

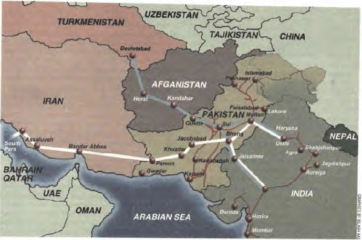

Offshore Iran, in an area of the Persian Gulf known as South Pars, lies a resource that could redirect the course of history in Southasia, 3000 km to the east. The resource is natural gas – essentially methane – and its import has become necessary in order to feed the demand for energy in faraway India. And so a gas pipeline is proposed that will traverse the Makran coast that Alexander walked during his last, ill-fated campaign, traverse the Balochistan-Sindh desert to Multan, and cross the Indus River to arrive finally in Rajasthan – to quench the thirst for energy of the Southasian economic behemoth. Along the way, the gasline would also top up the energy needs of Pakistan, whose own known reserves are expected to run out in a dozen years.

Till only a couple of years ago, this was a pie-in-the-sky project to all but a few visionaries – there is no other word to describe them – who understood how a long pipe carrying gas could also serve as the mother of all confidence-building measures. For the passage of natural gas through Pakistan to India, its price set at a fair level by Tehran and its uninterrupted flow guaranteed by Islamabad, will change the geopolitical landscape of the Subcontinent. In one stroke, the joint stakeholding of an economic resource will defuse the five and a half decade long India-Pakistan hostility. Many tightly-wound bilateral problems, including the matter of Kashmir, will suddenly become manageable.

Indeed, the geopolitics of Southasia will be transformed the moment the New Delhi housewife is able to turn on the tap for cheap natural gas piped directly into her kitchen, finally rid of the cumbersome red cylinders of liquid petroleum gas (LPG) that have been her burden for decades. Even more significantly, natural gas via pipeline will provide Indian industry with a massive boost in sectors ranging from petrochemicals to fertilisers; electric power production will increase dramatically and a myriad of new commercial uses will be supported. Once Pakistan begins to receive transit fees that could run to USD 600 million yearly and Islamabad is asked to give international undertakings not to turn off the tap in any circumstance, a threshold will have been crossed in India-Pakistan relations.

For long, hard-headed state-centric analyts in Delhi and Islamabad regarded the pipeline proposal as one prepared by and for romantics who floated outside the perimeter of reality. Perceptions began to change when the Federal Cabinet in Islamabad approved the concept of a gasline to India and President Gen Pervez Musharraf announced that he would allow unconditional passage of Iranian gas. The immediate reaction across the border was skepticism fuelled by the inertia of the intelligence and foreign policy establishments. Horrors! How could Pakistan be entrusted with a resource whose blockage would devastate a dependent Indian economy? What if Islamabad turned off the tap? “This project is a lemon,” announced a New Delhi heavyweight to his colleagues.

What sustained this undercurrent of attention was a diligent reflective exercise, underway since 1995, to study the economic feasibility of transporting Iranian gas to India with an eye to the peace dividend to be collected. Very few people outside of a close-knit circle even knew of the Balusa Group, a ‘track two’ effort that had been laying the ground for new thinking. Rounded up by a brother-sister émigré twosome born in India, brought up in Pakistan and naturalized in the United States – one an energy specialist and the other a senior foreign policy player in Washington DC – the group had been engaged in the study of India-Pakistan relations, with special attention to natural gas linkages, for nearly a decade.

Like everything else, the gasline proposal has had to ride the ups and downs of the turbulent India-Pakistan relationship. For a long time, progress was “out of phase,” as one analyst put it, with India turning a stiff upper lip when Pakistan was willing to go ahead with the pipeline and vice versa. But such was the unshakeable economic logic behind the idea that it defied the unremitting bilateral setbacks.

The realignment of regional geopolitics following the 9/11 attacks in the United States unexpectedly threw up possibilities to jump start the peace process, and the real breakthrough came in Islamabad on the sidelines of the Twelfth SAARC Summit, when Gen Musharraf gave Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee an undertaking not to permit any territory under Pakistan’s control “to be used to support terrorism in any manner.” This commitment paved the way for an inter-governmental ‘composite dialogue’ on a range of issues, and along the way the ‘track two’ pipeline project suddenly became kosher and was made part of the official ‘track one’ process.

Not that the gasline was a new concept. As far back as 1989, the head of the Tata Energy Research Institute (TERI), R K Pachauri, had brought Iran’s former Deputy Foreign Minister Ali Shams Ardekani to New Delhi to deliver a paper on the subject. Pachauri recalls, “At that time, policy makers and others thought of it as nothing more than a pipe dream. But what you need are rational thinkers and policymakers who can identify win-win opportunities.” Somewhat before the India-Pakistan thaw of the last couple of years, the Balusa Group had predicted, “Major shifts in political relationships do sometimes take place at baffling speed and in totally unexpected directions.” This is indeed what has happened. The Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline is now within grasp, and with it the hope that the continuous inferno of India-Pakistan relations may finally be smothered under a blanket of methane.

Interestingly, it was the prolonged military standoff of 2002 that Rawalpindi-based ‘activist-general’ Mahmud Durrani thinks has “convinced the leader-ship of both the countries that war of high or low intensity is no more a practical option.” A Balusa member from the start, Gen Durrani says, “While the Indian and Pakistani people, in spite of the occasional hysteria, have always wanted to live in peace, this is the first time that I see a change in the thinking of the establishments of our two countries. Understanding of the cost of conflict and benefits of peace is finally sinking in, which is why our pipeline proposal is no more a pipe dream.”

Iran, which has the largest natural gas reserves in the world after Russia but exports only to Turkey, is keen to open up markets eastwards in Pakistan and India. But even the Iranians are quick to emphasise the importance of the gasline to Southasian peace-building. Tehran’s Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi said in Delhi in early February, “We are convinced that the Iran-India pipeline through Pakistan will benefit all three countries and substantially improve the political and economic relations between India and Pakistan.” Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Shaukat Aziz, has no doubts on that score: “I have always said that if we create mutual linkages and mutual dependencies, that helps the overall political framework.”

The optimist’s timeline Pipeline gas is attractive because of its competitive price and stable and long-term supply. The extended multinational gaslines in operation, such as those from Siberia to Germany and from Algeria to France, have already proven the technical, economic and geopolitical viability of such projects. Pakistan has had decades of experience with its own domestic natural gas network, which branches out to all regions from the gas fields of Balochistan and Sindh. Natural gas is the fuel of choice of the twenty-first century: it is cheaper and cleaner than most alternatives and it is found within easy reach in the outlying regions of Southasia, from Burma to Turkmenistan and Iran.

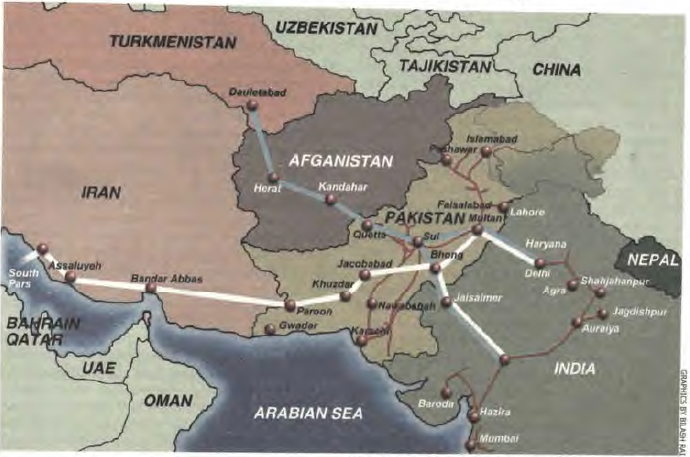

Both the Indian and Pakistani economies are expected to grow at more than six percent yearly for the next decade. Their hunger for energy is already acute and their own proven gas reserves are quite modest in relation to projected demand. India presently requires 120 million standard cubic meters per day (mmscmd) of natural gas, which is over one-and-half times the supply of 70 mmscmd. The demand is expected to go up to 250 mmscmd by 2010, and rise to 400 mmscmd by 2015. An overland pipeline being 30 percent cheaper than transporting liquefied natural gas (LNG) by tanker ships, it is obvious why the Iranian gas fields look so tantalizing to the Indian energy planner.

It was only a few years ago that, in an environment that stands in sharp contrast to the Indo-Pak bonhomie of today, the gasline idea was stalled simply because New Delhi did not want Islamabad to benefit from the transit fee. And there were some in Pakistan who did not want India to prosper through easy access to Iranian gas. This dog-in-manger mindset also stalled progress through the introduction of conditions: New Delhi wanted road transport access to Afghanistan as quid pro quo and also demanded the Most Favoured Nation status from Pakistan; like-wise, Islamabad was quick to link the pipeline with progress on the ubiquitous problem of Kashmir.

In the improved atmosphere of today, with political will evident on both sides, the issues have been separated and the Iranian pipeline stands alone and on its own merits. Most importantly, the pipeline’s chaperones in New Delhi’s Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas have managed to convince the political front rank that the project must be seen solely as a project for energy security, vital for the economy’s growth. Things are so close to a breakthrough that India’s Petroleum Secretary S C Tripathi told reporters that if the negotiations between Islamabad, New Delhi and Tehran went smoothly, ground could be broken within two years and the natural gas could actually begin to flow by October-December 2009.

Even discounting such an optimistic scenario, the peace-building potential of the gasline is already beginning to kick in as the three countries start to discuss the modalities of the project. The vital need for natural gas imports is already informing rhetoric in New Delhi and Islamabad and playing a part in modulating positions. This trend will continue as the construction of the pipeline proceeds and the facts of an intertwined Indian and Pakistani economy are, literally, created on the ground. And so, the scene is set for a USD 5 billion project that would place a pipe of 56 inches diameter and 2700 km length to carry gas under pressure from the offshore South Pars gas field to Delhi and Gujarat, carrying 3.2 billion cubic feet of gas a day. The matter is no longer one of ‘if, but ‘when’.

Bhai-Bhai Bonhomie

It is the coincidence of leaderships in Islamabad and New Delhi that has delivered a permutation capable of propelling the gasline project. Pakistan is ruled by a general president who is largely unencumbered by political obligations and who sees the achievement of peace with India as a crowning glory that could wipe away the stain of autocracy. The presence of international banker-turned-prime minister Shaukat Aziz enhances Gen Musharraf’s understanding that beyond bhai-bhai bonhomie, sustainable peace must be built by means of permanent economic linkages with India.

On the side of democratic India, the economist Manmohan Singh was catapulted to the helm of affairs when Congress Party president Sonia Gandhi unexpectedly declined the prime minister’s chair in May 2004. The architect of India’s economic liberalisation as finance minister under Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao in the early 1990s, Singh instinctively understood the value of the gasline for India’s expanding economic base. Being a non-political animal, incongruously akin to the general across the border, it was easy for Singh to follow his professional instincts rather than be bogged down by the heavy weight of geo-strategic cautionary counseling.

Manmohan Singh’s choice for the Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas in the Union Cabinet has been key to the rapid developments on the gasline front over the last year. Mani Shankar Aiyar was a foreign service officer from the Tamil south, a friend of Rajiv Gandhi who emerged as a staunch loyalist of his widow Sonia. The loquacious Aiyar, actually born in Lahore in 1941, considers his three year stint as India’s consul general in Karachi as a defining period of his life and was an unabashed advocate of bilateral contact even during the worst days of Pakistan-bashing in India. Aiyar’s confidence also comes from the fact that he is an elected Member of Parliament rather than a nominated elder of the Upper House. Even his critics grant Aiyar his flamboyance and mental capacity.

When the United Progressive Alliance coalition government was being formed following the rout of the BJP in May 2004, Aiyar first took on the post of Minister for Panchayati Raj, local government being an area of personal interest. Manmohan Singh had also promised him a more ‘heavy’ ministry, while Aiyar was given ‘temporary charge’ of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas. For some reason, no one has told him to move on and, typically ‘Mani Shankar’, Aiyar lost no time in pushing the idea of the gasline. It was a stroke of good fortune that, together with Jaswant Singh of the BJP, Aiyar had been a participant in the Balusa conclaves and the two had even made a joint report to South Block in 1996 on the merits of the Iranian gasline concept (see interview).

Aiyar raided his former employer, the Ministry of External Affairs, and brought over a respected diplomat named Talmiz Ahmad to his own mini-shy on secondment to serve as Additional Secretary (Overseas). Ahmed was to organize and pacify while Aiyar led the charge. With Indian industry firmly on his side for the bonanza that Iranian gas represents, Aiyar’s challenge was to get Manmohan Singh’s ear and to keep at bay the security analysts whose livelihoods depend on stoking the embers of bilateral tension. Soon after he took office, he provided the cabinet with a note on energy security, arguing for pipeline imports. On 9 February 2005, the cabinet gave him formal clearance to conduct what Aiyar calls “conversations without commitment” with Burma, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and Iran.

Another coincidence is the matter of Aiyar’s rapport with Pakistani Foreign Minister Khursid Mahmud Kasuri: “a friendship which goes back to 7 pm, 8 October 1961, Trinity Hall in Cambridge”, says Aiyar with his trademark flair and memory for detail. When Kasuri was in Delhi on 5-6 September 2004 to review the status of the composite dialogue with Natwar Singh, he and his wife came over to Aiyar’s house for dinner. There, the college-mates worked out a formulation that was incorporated into the joint statement issued by the two foreign ministers at the end of Kasuri’s Delhi visit. It was during that conversation that the term ‘hydrocarbon cooperation’ entered the bilateral dialogue. A few weeks later, in New York, Manmohan Singh and Pervez Musharraf issued a statement which said that “a gas pipeline via Pakistan to India . . . could contribute to the welfare and prosperity of the people of both countries.”

Being a pushy sort of person, all-powerful Sonia’s confidante, and willing to dare the system, Aiyar immediately made it a cause to promote not only the Iranian pipeline but a veritable Southasian gas grid. Before anyone could tell what was happening, he was proposing the extension of the Iranian gasline all the way east past the Ganga and Brahmaputra plains to Yunnan to supply southern China. He visited Burma and Bangladesh and convinced his counterparts to cooperate on the building of a pipeline to bring offshore Arakan gas to eastern India.

Aiyar’s trump card as far as the nay-sayers are concerned is the energy projections, which juxtapose an exponentially expanding Indian economy with the fact of limited or uncertain domestic reserves. His simple question is, “How are we supposed to fill in for the shortfall of energy?” Aiyar likes to say that the twenty first century is going to be the century of natural gas, just as the previous two were those of petroleum and coal respectively. He wants India to be firmly a part of the natural gas century.

Notable advance was achieved on the pipeline front after Aiyar visits Pakistan and Iran in early June. In Islamabad, discussions were held with Pakistan’s Minister of Petroleum and Natural Resources, Amanullah Khan Jadoon, where the brass tacks of the gasline were discussed, including transit fees, security guarantees and continuity of flow. After a stopover in Baku in Azerbaijan to attend the 12th International Caspian Oil and Gas Pipeline Conference, Aiyar arrived in Tehran to sign an agreement to buy LNG and to discuss the pricing of the piped gas on offer. From both capitals, Aiyar brought back understandings to proceed with the planning of the gasline.

India-Pakistan Gas

Pakistan ‘understands’ natural gas as a resource somewhat better than India does. It is decades ahead of the rest of the region in its extraction and exploitation of the resource – in pipeline infrastructure, in transportation, and in industrial, commercial and residential use. Whereas everywhere else in the Subcontinent stand-alone industrial generators run on diesel, in Pakistan natural gas is the fuel of choice. Homemakers in Pakistan have never seen the ungainly steel LPG canisters that must be lugged to and from kitchens in the rest of Southasia outside of Bangladesh.

Pakistan got its head start with the discovery of a gas field in Sui of Balochistan in 1951, which even today supplies 45 percent of the country’s distributed gas. The first pipeline, which went down to Karachi along the Indus, was built in 1955. By the late 1960s, two companies, Sui Southern and Sui Northern, were providing service through a countrywide network of pipelines that extended from Peshawar to Lahore to Multan. Bangladesh had a somewhat later start in gas exploitation (Mani Shankar Aiyar: “The country is floating on a lake of natural gas!”), but neighbouring India has barely begun to wake up to the possibilities of this fuel.

The fact that Pakistan is the Southasian path-breaker in natural gas is clear from a comparison of pipeline networks. Altogether, Pakistan has 7900 km of gas pipelines, whereas the much larger India has no more than 4000 km of unconnected lines. What goes for a grid in India is confined to one 1700 km pipeline that connects Hazira in Gujarat with Delhi and Haryana. The energy mix in the two countries is also worth contrasting: in India it is 54 percent coal, 32 percent oil, nine percent natural gas and three percent hydropower. Pakistan presents an entirely different picture, with 45 percent reliance on oil, 41 percent on natural gas and nine percent hydro.

Sui Southern and Sui Northern are considered efficient parastatals fully capable of involving themselves in the Iranian gasline project from the Pakistan side. The main producers of gas in India are the Oil India Limited (OIL), which operates in Assam and Rajasthan, and the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), which works on the offshore fields of the Arabian Sea. The Gas Authority of India Limited (GAIL) was established in 1984 to handle infrastructure and marketing of gas and runs today’s modest network. It is expected to be the main entity that will distribute the Iranian gas from the point at which it enters Rajasthan. It is expected that the gasline will bifurcate to feed the Gujarat and Delhi regions.

Says TERI’s Pachauri, “In India, the biggest impact of piped gas at reasonable price on a large scale would be seen on power generation and the production of fertilizers and petrochemicals. Extensive distribution for residential use would probably not happen right away. On power generation, India has plans to add capacity of about 10,000 megawatts every year and natural gas would be the fuel of choice.”

TAP on tap

While Iran is the favoured source by which to fulfil India’s current and projected energy thirst, it does not provide the only available. There have been extensive negotiations and several memoranda of understanding signed, for example, with Qatar or Oman. But the route under the Arabian Sea is considered impractical because of cost and unproven technology. The most obvious alternative to the Iranian gasline is the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan (TAP) project. The three governments have been in consultation on the matter since 1999, and a detailed feasibility study has been carried out on a line that would transport gas from the Dauletabad reserves of Turkmenistan all the way to Multan.

The TAP line, as proposed by a UK company hired by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), would have a pipeline of 56 inches diameter running a distance of 1680 km, with capacity of 3.2 billion cubic feet per day. The cost of construction would be 3.3 billion USD. Says the ADB report to the three countries, “Based on the projected gas demand in Pakistan, the TAP project is feasible and has high potential.”

TAP is also known as the “old Unocal project”. During the time of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, the multinational company Unocal succeeded in persuading the mullahs to consider the project. Unocal put together a consortium in 1999 and opened offices in Pakistan and India, signing agreements also with vehement opponents of the Taliban in Afghanistan’s north. In 1999, as opposition to the Taliban grew in the West and investors were made nervous by the extended Afghan civil war, Unocal withdrew from the project.

Says Gen Durrani in Rawalpindi, “If the GDP growth of India is to be sustained you will need more than one pipeline. Geographically, TAP is the easiest, down through western Afghanistan and Pakistan. Politically, the Iranian pipeline is the simplest, because there is no turbulent Afghanistan in between, and you are also dealing with one less country. My own suggestion would be to first go for the Iranian pipeline, and then for TAP, and after that the Qatar pipeline which will have to come undersea and then through Balochistan.”

Mother of all CBMs

The maturity that has suddenly come to mark the India-Pakistan relationship is hard to comprehend given the acrimony of the past. But while confidence-building efforts are welcome, feel-good measures that merely emphasize the bhai-bhai nature of the India-Pakistan interface will not be enough to stabilise the relationship. Goodwill and atmospherics can evaporate all too quickly in the aftermath of an accident or untoward incident, leaving behind bitterness and added distrust. To make an amicable relationship stable, it is essential to have free movement of people across the India-Pakistan border with safeguards only to prevent mass migration. At the same time, it is urgent to begin the process of establishing economic facts on the ground that will cement the newfound amity. The Iranian gasline, or alternatively the TAP line extended to India, would provide such a binding element, a cushion to help the two government overcome the political ups and downs that are bound to occur.

Much of the animosity towards Pakistan within India is concentrated in the northern states of Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Punjab and Delhi, which were most affected by the demographic shifts and the violence of Partition. These northern Indian states are the ones that would benefit directly from the gasline from across the Thar Desert. It is hard to underestimate the impact of the gasline project as a confidence-building measure, or CBM. The immediate benefit of piping gas from Pakistan into India would be to lock the two economies into an embrace after decades of separation, closed borders and the absence of economic reciprocity.

There is, intriguingly, no dearth analysts who sing the praise of the pipeline idea, and these include the hard-headed ones. Amitabh Mattoo is a political scientist who serves on the Advisory Board of India’s National Security Council and was recently appointed Vice Chancellor of Jammu University. He says, “If you believe that the India-Pakistan conflict is structural, then the only way to defuse it is to build a relationship of economic dependence. Looking to the future, the gas pipeline can be seen as almost the equivalent of the European Steel and Coal Community, which served as the basis for the European Community. The best confidence-building measures are those where you build economic stakeholders, which the pipeline will do. It will achieve in a year what SAARC could not do in a decade or more. In addition, there will be a multiplier effect across the region as a whole if India and Pakistan come together.”

C Raja Mohan, an expert on strategic affairs presently at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, has been following the pipeline project for more than a decade and is convinced that its newfound respectability is based on sound logic. He says, “This is a transformatory project, and it will fundamentally change the nature of interaction in the Subcontinent. It will break the wall of suspicion by promoting economic interlinkages, which will begin to take hold once large corporations like Reliance get active across the border. A frontier of conflict will be converted into a frontier of contact.”

Mahendra P Lama and Rasul Bakhsh Rais, scholars from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi and Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad respectively, have no doubt that “gas pipelines for a common future” is an idea whose time has come. Together, they have written that “such a grid would generate a chain of stakeholders at the level of policymakers, institutions, consumers and beneficiaries, with forward and backward linkages. This could be one of the single biggest confidence-building measures between the two countries, and would create positive and permanent vested interests in South Asia.”

The ‘forward and backward linkages’ of the Iranian pipeline will reach into the deepest nooks and crannies of the two economies. Beyond the industrial, commercial and household-level advantages, the gasline will also serve as a powerful symbol of cooperation and interdependence. Gen Durrani says of the prospects: “The peace dividend will begin to flow the moment you sign the document. There will be newfound confidence as you move into detailed studies, construction, the to-and-fro between officials, and so on.”

The economic dividend that India and Pakistan will reap from cheap and reliable Iranian methane will create stakeholders for peace in the economic sectors of both the countries. The involvement of industries large and small will lead to a vested interest in geopolitical stability between India and Pakistan. Take the example of Reliance Industries, India’s petrochemical giant, which is expected to make heavy use of the natural gas that comes through the pipeline. It would be in the company’s interest, once the pipeline is in place, to have bilateral tensions low so that its coffers remain full. The same would hold true for all other industrial and commercial players.

The pipeline even has the power to restrain the two countries on the issue of Kashmir, the key yardstick by which any proposed India-Pakistan CBM must be measured. Write Lama and Rais, “The pipeline may ultimately de-prioritise the Kashmir issue from the agenda of the political economy of India-Pakistan relations.” In New Delhi, TERI’s Pachauri has no doubts on that score: “If India gets large quantities of gas at a reasonable price and Pakistan benefits from the economies of scale and transit fees, Kashmir and other bilateral problems would be seen to be ridiculously trivial. If cricket matches and bus services between the two countries can demolish so many prejudices, surely the cementing of such a large-scale economic relationship would create unprecedented goodwill on both sides. There is a potential for radically altering mindsets.”

But can the hawks and ultra-nationalists on both sides still gather enough energy to sabotage the gasline proposal? Fakir Ayazuddin, a Karachi businessman and commentator, thinks that the momentum that has been generated will carry the project past such obstacles. He says, “De-escalation will begin the moment the pipeline deal is signed, and the hawks will be sidelined. At that point, the cynics and opportunists who work overtime to poison bilateral initiatives will have no possibility of open opposition. There is too much good in the proposal.”

Balusa

Toufiq Siddiqi is an environmentalist and energy expert based in Hawaii. Shirin Tahir-Kheli is a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University, currently Senior Advisor to Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice on United Nations Reform, who served on the US National Security Council from 2003-2005. Born in Hyderabad (Deccan) before Partition, the siblings spent part of their childhood in Pakistan, after which they became Southasian émigrés in the US. In the early 1990s, Siddiqi became interested in the energy requirements of the Subcontinent, while sister Tahir-Kheli maintained her interest in the region even as she rose up the career ladder in Washington DC.

With support from the United Nations Development Programme and the Rockefeller Foundation, the brother-sister duo brought together a group of Indian and Pakistani generals, politicians, bureaucrats and others to discuss ways to bring sense and direction to the India-Pakistan relationship. It was this loose gathering that came to be known as the Balusa Group, named after two adjacent villages in Pakistani Punjab. (The group, labelled “a five star track two effort” by one critic for the high profile of its members, includes a few irreverent individuals who enjoy such mischief as making the claim that “Balusa evidently means peace in an ancient Indian language”.)

The group brought together by Tahir-Kheli and Siddiqi first met in Singapore, which was followed by gatherings in Bellagio (Italy), Muscat (Oman), Udaipur, Rawalpindi and elsewhere. The latest was a discussion on Kashmir held in Chandigarh in February 2005. A leading figure in the Balusa Group is Mahmud Durrani. While a serving general, he had announced to Tahir-Kheli in 1994 his intention to devote his imminent retirement to helping achieve an India-Pakistan rapprochement. With the support of some progressive-minded top brass in the Pakistani

military, Gen Durrani became active in the Balusa conclaves. A firm advocate of economic linkages to concretise peace initiatives, he believes the group has been “way ahead of the curve” on the gasline proposal. (see interview).

Recalling the beginnings of the Balusa initiative, Siddiqi says, “Shirin and I have had a continuous interest in promoting sustainable development in the Subcontinent, and here was a concept that would represent a win-win economic situation for the key adversaries, while also serving as a CBM. I knew many of the energy and environment experts in both countries, whereas Shirin knew many of the policymakers. We understood that given the magnitude of energy requirements, the natural gas pipeline offered the greatest potential.”

Yankee Veto

The idea has never been this close to becoming a reality, but a number of things could still go wrong. Most significantly, the building of the gasline depends on the absence of accidents along the way that could derail the larger peace effort – a massive militant attack, an assassination or any other event with potential to fuel nationalist reaction and tie the hands of even the most clear-headed president or prime minister. Other, less dramatic obstacles could emerge as well: Iran could ask for too high a price for its natural gas, or Islamabad could put an unrealistic tag on the transit.

Militancy along the proposed pipeline(s) is a source of worry for planners. The dangers for TAP would be in the continuing troubles in western Afghanistan, while the Iranian pipeline project is threatened by brewing discontent in Balochistan, through whose territory it would run for 750 km. The source of possible trouble are Baloch militias unhappy with the price their province is receiving for Sui gas. The militias have been setting off explosions along Pakistan’s domestic pipeline network. Experts in Islamabad, however, discount the level of the threat to the Iranian line, which would have no connection to the source of Baloch discontent. They say that Pakistan as the transit state would have to provide ironclad guarantees against disruption, and that a dedicated patrolling force (perhaps the Pakistan Army on contract) and high technology remote monitoring would largely take care of the problem.

The greatest worry by far with regard to the future of the pipeline proposal, however, is not the Afghan or Baloch tribesmen but the Government of the United States of America. Currently engaged in a jousting match with Tehran with regard to the latter’s nuclear ambitions, the Americans have made it clear that they eye the possible deal between the Southasians and Iran with distaste. At a press conference on 16 March during her first trip to New Delhi after taking office as Secretary of State, Condoleeza Rice conceded that Southasia had growing energy needs. But then she added, “I think that our views concerning Iran are very well known by this time. We have communicated to the Indian government our concerns about the gas pipeline cooperation between Iran and India.” The State Department once again growled, through a spokesman, when India’s Aiyar visited Pakistan and Tehran in early June to push the gasline project.

The fact is that the sanctions America slapped against Iran in 1984 following the extended hostage crisis that brought down the Carter Administration are still in place and prohibit American companies from working with Tehran. In addition, there is the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act of 1996, which provides penalties even for third-country companies that work with Iran. If they decided not to look the other way, the Americans are in a position to lean heavily on a very US-dependent Gen Pervez Musharraf and nudge the gasline proposal towards the cliff.

Rice’s statement sent shock waves through government and industry in India and Pakistan, but the official Southasian response has been marked by a show of bravado, one that could well dissipate if the screws were to be tightened. Standing by Rice’s side at the press conference, Indian Foreign Minister K Natwar Singh said, “We have no problems of any kind with Iran.” Minister Mani Shankar Aiyar likes to emphasise the civilisational ties India has with Iran and the importance of Iranian gas for eradicating poverty in Southasia as a whole. Across in Pakistan, Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz has said that Pakistan will make a decision on the project based on the national interest and nothing else, while petroleum minister Jadoon says Pakistan needs natural gas and will look at all options of supply, including Iran.

It is possible, however, that the Americans will not go all the way in opposing the project. One New Delhi bureaucrat who is crossing his fingers likes to point out that Rice did not actually raise the matter of the Iranian pipeline in her bilateral talks with South Block, and what she said, was only in response to a question from the press. Indeed, the US may not want to be seen as coming out against a project that would contribute directly to lasting India-Pakistan peace. Or a project that would help uplift the economy of all of Southasia, the most depressed populous region in the world. Would Washington DC be willing to put a spanner in the works of a project that practically has a halo around it?

How far will the Americans go? Mani Shankar Aiyar says we will not know until the project-related agreements are signed. On the whole, the expectation is that the US will compartmentalize its attitude and animosities towards Iran so that they do not affect the Iranian gasline to Southasia. As Siddiqi has written, “Were India and Pakistan to come to a satisfactory deal and to jointly confront US policy on a project which could change the face of South Asia, Washington would indeed have to take a long hard look.” The Karachi commentator Fakir Ayazuddin is sitting back confident that the Indian umbrella will provide adequate protection to the gasline: “It is easier for the Americans to slap Pakistan than to anger India. The Indian lobby in Washington DC will work to ensure that America doesn’t stop the pipeline.”

Land of Southasia

On the basis of the rapprochement already achieved between Islamabad and New Delhi, Aiyar’s successful trip to Islamabad and Tehran in early June, and the unlikelihood of a US filibuster, it is a near certainty that the Iranian gas pipeline will come into being, confounding critics and promoters alike. The gasline is exactly the interdependence-creating project needed to protect the bilateral relationship from being buffeted by accidents, aberrations and opportunistic ultra-nationalisms on both sides. The economic merits of the Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline are clear to anyone who can prepare the most basic economic model and forecasts.

It bears remembering that Southasia is a region where the nuclear sabres were rattling just half a decade ago, with talk of atomic annihilation. There is no densely populated, poverty-stricken, fractious region in the world more in need of a confidence-building measure. It is a fair development that governments who were glaring at each other across the barbed wire frontier are today talking of building an umbilical gasline which would tie their two economies together.

For Toufiq Siddiqi of the Balusa Group, the argument for the project is simple: “The demand for natural gas is expected to almost double in India and Pakistan over the next decade. This cannot be met through domestic production. The two countries would need to import from neighbouring regions. It is in the interest of India and Pakistan to import natural gas via a common pipeline.”

When simple arguments win the day, we will have turned the leaf to the future. The land of Southasia is poised at the start of a new beginning; this much one can say without being accused of romanticism.

Energy in the East

Not satisfied with its explorations westwards, India is also looking to the east in its quest for energy security. In January 2005, plans for a pipeline carrying natural gas from the fields of Burma to India through Bangladesh were approved, in principle, by the energy ministers of the three countries. The gasline has been termed a ‘win-win-win’ opportunity for all concerned, with Burma gaining access to new markets, Bangladesh earning transit fees and India quenching its ever-increasing thirst for energy.

While Burma is estimated to have abundant natural gas reserves, India is already facing a massive shortfall in supply (see graph on page 32). The gas in question would be transported from the offshore Shwe fields in the Arakhan province of Burma. The route of the pipeline, to be decided on the principle of “ensuring adequate access, maximum security and optimal economic utilization”, would most likely pass through the Indian states of Mizoram and Tripura, entering Bangladesh at Brahmanbaria and crossing over into West Bengal through the Rajshahi border.

An interesting aspect of the trilateral ministerial agreement is that Bangladesh and India are allowed to use the pipeline to “inject and siphon off their own natural gas.” This means that India would be able to feed gas from its Tripura gas fields into the pipeline and then extract it once the pipeline reaches West Bengal. And Bangladesh could use the gasline to transport gas from the eastern Sylhet region, where its reserves lie, to its west.

The project’s benefits to Bangladesh include about USD 125 million a year in transit fees. Dhaka is also assured of supply of Burmese gas should its own reserves begin to run out. The Burma gasline gains additional significance against the backdrop of Dhaka’s reluctance to export its own natural gas to India, a reticence ascribed to both doubts about the size of its reserves and the dynamics of Bangladeshi politics, which make exports to India problematic. The Burma pipeline could help relax such attitudes in Dhaka in the future.

The January agreement, meanwhile, has hit a patch of bad weather, with a set of conditions set by Bangladesh on India. As part of a quid pro quo, Dhaka wants Delhi to provide it with transit facilities for import of hydroelectricity from Nepal and Bhutan, as well as measures to reduce the trade imbalance between India and Bangladesh. Bangladesh has also demanded access to a corridor through India for trade with Nepal and Bhutan. With India refusing to include bilateral issues in a tripartite agreement, the signing of a Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU) in April was deferred. The political risk involved in signing an agreement with India on the eve of an election may be weighing heavy on the minds of the ruling dispensation in Dhaka.

There is also opposition to the gasline from Burmese pro-democracy activists and some international groups. They argue that the deal, pushed by Bangladesh and India as Southasian democracies, would simply strengthen and legitimise the authoritarian regime in Rangoon. With the recent ‘realist’ tilt in New Delhi towards the Burmese ruling junta, and given the country’s energy needs, it is unlikely that India for one will be swayed by the opposition. If this situation holds, if Dhaka relents and if an understanding does get formalised this year, officials estimate that Burmese gas could be flowing to Calcutta industries and households within five years.

by Prashant Jha

Interview

“The issue is fundamentally settled.”

Mahmud Durrani, retired Major General of the Pakistan Army, was interviewed in his home by the 18-hole Rawalpindi Golf Course.

Himal: How did a general get into lobbying for natural gas pipelines?

Mahmud Durrani: Shirin Tahir-Kheli is really the mother hen of all this. I was still in service when I told her of wanting to retire and devote my life to promoting India-Pakistan peace. Within two years, she and her brother Toufiq had organised a group of Pakistanis and Indians to discuss energy cooperation. I attended the first meeting with the backing of the Pakistan military and the government. There was a feeling that we needed peace. There was even an ex-RAW chief in our group.

Do you feel vindicated?

Now that the pipeline project seems within grasp, the members of the Balusa Group feel redeemed. What we had thought of as close to a dream is now close to reality. The idea is do-able, it is economically feasible, and we are excited.

Were you always convinced about the project’s feasibility?

In seeking to learn all there was to learn about natural gas pipelines, I met with a representative of Reliance Industries at the Indian International Centre in New Delhi. They were already into gas, and felt that the pipeline would work. This added to my confidence.

Were you not wary of meeting up with big businesses such as Reliance?

I got over that kind of timidity long ago. One must respect the private sector as a partner, and I had no problem meeting with the Reliance people. For a peacenik, industry can be a very strong partner.

Are there those in Pakistan who will reject the project?

Only the narrow-minded extremists. The project will move ahead on its own merits sooner than later, and the gas will help develop stakeholders across the border.

Are we expecting too much from one pipeline?

The pipeline is not a magic wand that will resolve all problems at one wave, but please understand that exporting gas is completely different from exporting sugar or potatoes. Simply put, a gas pipeline cannot be shut off, therefore it can provide more stability than other kinds of cross-border exchange.

Are you worried about the troubles in Balochistan affecting the pipeline?

There is disaffection in Balochistan, but this does not provide the motivation to blow up a transit pipeline from Iran. Nevertheless, adequate security arrangements will have to be there. A lifeline for Indian industry cannot be made insecure.

Are you sure it will happen?

I think the pipeline will happen, not as a romantic but as a realist. India needs the gas and Pakistan needs the gas. They have in the broader sense agreed to cooperate on this. The issue is fundamentally settled.

A Nepal-Bangladesh win-win

by Rajendra Dahal

Just a decade ago, the roof racks of passenger buses arriving in any one of Nepal’s cities and towns would be piled high with firewood. All through the tracts of jungle along the highways, stacks of firewood would be on sale. However, no firewood is entering the cities of Nepal today. What is it that has marginalised firewood?

The answer is cooking fuel. Earlier, the only fuel was firewood. Then there was the shift to kerosene three decades ago, and after that, the rapid spread of liquid petroleum gas (LPG) canisters. Now, the red coloured LPG cylinders have become so popular that they are even carried on porter-back and mule-back to remote mountain villages.

Today, the forests of the mountains and jungles of the plains are regenerating in large parts, as is evident not only along the highways but also along the Kathmandu Valley rim. While Nepal’s successful implementation of community forestry has been given the credit for this sudden greening, the role of reduced firewood demand around the population centers must be acknowledged. In the absence of alternative fuel, the efforts of local forest user groups alone would not have been enough.

Even though scientifically un-proven and a matter of conjecture, there is a common perception that a lot of the monsoon flooding and siltation, including in Bangladesh, is caused by the loss of tree cover in the central Himalaya. With kerosene and LPG already making such a difference to Nepal’s forests, one can visualise the situation if natural gas were to arrive from Bangladesh by pipeline. Available for much cheaper than today’s LPG canisters, natural gas would accelerate the shift away from firewood, which would further reduce deforestation.

The gasline to feed Nepal would reach out from the north Bengal town of Bogra, cross 40 kilometers of India’s Chicken’s Neck and arrive at the Nepali border town of Chandragadhi across the Mechi River. Chandragadhi could be the main depot, from where, pending a pipeline to Kathmandu and elsewhere, tanker trucks could distribute natural gas around the country.

Indian and American multinationals have been pressurising the Dhaka to export natural gas from its Sylhet reserves to India-. The official reason cited for Dhaka’s reluctance is its insecurity about the size of the national gas reserves. Because the volume of Nepali demand would be relatively low, Bangladesh should not be worried about excessive depletion of its reserves. Besides helping green the Nepali hillsides and – as the suggestion goes – help reduce flooding, Bangladesh would also be helping the population and economy of a fellow SAARC member.

The project could also be a harbinger to greater cooperation in the field of energy resources, with Nepal subsequently exporting its own hydropower to electricity-deficient Bangladesh. A gasline and electricity linkage between the two countries would also serve as an important element in the larger Southasian energy grid that Indian Energy Minister Mani Shankar Aiyar, among others, is proposing.

The logic and benefit of a Nepal-Bangladesh link are obvious and if serious efforts are made by the two sides, sources say that India is unlikely to create obstacles in use of its territory for transit. The tripartite agreement between Bangladesh, Burma and India of January this year, approving, in principle, the export of Burmese gas to India via Bangladesh territory also augurs well for increased flexibility among all governments of the region when it comes to grids and pipelines. Additionally, if Bangladesh is unable to export its own gas to Nepal, it would now be possible for the latter to get access to the Burmese gas.

There will come a time when, with natural gas changing the energy scenario, Nepali villagers will stop entering the forests for firewood. The mountain forests will turn even more verdant. As Bangladesh exports gas to Nepal, Nepal will stop exporting silt to Bangladesh.