From Himal Southasian, Volume 19, Number 3 (MAY-JUN 2006)

Hum dekhenge …

Jab takth giraye jayenge

Sab taaj uchale jayenge*

Well, the virtuous people of Nepal saw to it that the crown was dashed. Very late in the modern era, long after other countries of Southasia had experienced their uplifting, cathartic moments, Nepalis by their millions stood up against feudalism. People Power simultaneously pushed back a despotically inclined king, made space for pluralism, and created the conditions for peace. The mission now is to bring the Maoists in from the jungle while ensuring that the kingship is forever barred from mischief. Faiz Ahmed Faiz would have liked it here in Kathmandu this week, as would have Iqbal Bano, who sang that immortal people’s anthem.

Bangladesh achieved independence in 1971; the rest of Southasia, its freedom in 1947 and 1948. For Nepal, the heady days of popular participation for a common future were encapsulated in the spring of 2006. As predicted in these pages in our earlier issue, a sputtering ‘movement’ suddenly converted into a People’s Movement of colossal dimensions, fuelled by the scorn Gyanendra had continuously heaped upon the citizenry. Suddenly, the weakened, unarmed middle ground, represented by the political parties and civil society, gained the upper hand. Meanwhile, a hopefully chastened Maoist leadership saw a non-violent mass movement achieve where ten years of their war had failed.

A menacing autocrat who sought to rule on the basis of dynastic right, outright misrepresentation and military might, Gyanendra was incapable of acknowledging the political maturity of the people. Taking energy from an insular, self-serving Kathmandu Valley upper class, equally contemptuous of the political parties, he began appointing prime ministers at will in October 2002 and finally took over as head of government on 1 February 2005.

* We shall see …

When the crowns shall he toppled

When the palaces will be demolished

Gyanendra’s excuse for his army-assisted takeover was to fight the insurgency, but the intent was to maintain himself as a corrupt, all-powerful autocrat. His most unpardonable act was to militarise an innocent society, already devastated by years of insurgency. Fortunately, despite the worst of intentions, this man did not have the intellectual or organisational skills to run a police state.

Another spring

The people of Nepal first achieved democracy during another spring, 15 years ago, through a more modest people’s movement that delivered the 1990 Constitution. For 12 years till 2002, they experienced freedom and made the most of it. While the legacy of two centuries of oppression by Kathmandu’s rulers was difficult to undo in a dozen years of democracy, what pluralism did for Nepal was electric. A voiceless people discovered the power of speech; they developed a confidence unprecedented in their history.

This empowerment of the masses is what the feudocrat in Gyanendra never understood, and he would have been overthrown immediately after 1 February had a violent insurgency not been raging in the countryside. For a decade, that misconceived rebellion — one of Maoist chieftains making their own grabs for power, through the barrel of the gun — had sapped the energy of the nation. The politicians who were engaged in non-violent politics were caught between two guns. It was last autumn, when the Maoists conceded the failure of their ‘people’s war’ and agreed to come into open politics through a constituent assembly, that the People’s Movement became possible.

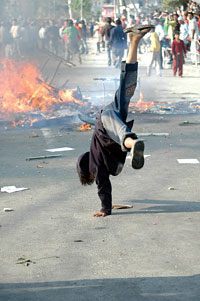

On 22 November 2005, tired of waiting for dialogue with a sneering Narayanhiti palace, and with the Maoists having already signalled their climbdown, the political parties signed a 12-point understanding with the rebels to fight the regime in parallel. The political rallies suddenly began to attract the public, now that the parties were able to promise a fight for the return of both democracy and peace. The participation in the rallies climbed to 50,000, a lakh, two lakh. Meanwhile, Gyanendra continued to display conduct specifically designed to emphasise his scorn for the common masses. Even as he was receiving felicitations as a ‘Hindu Emperor’ from a dreadfully organised meeting of conservative Hindus in the town of Birgunj, the movement sparked and took off. The bottled-up anger against the aberrant king exploded in the heady People’s Movement of 2006. It was a political tsunami of a force few could believe.

People in other parts of the Subcontinent have perhaps forgotten how it is to be one nation together fighting for a cause. The Nepali People’s Movement was a Southasian, Asian and global happening, where a people discovered the simple pleasure of fighting together for pluralism. And when Gyanendra sought to provide measly concessions — too little and too late — on Friday, 21 April, another people’s tsunami crashed against the Narayanhiti gates. Gyanendra’s resolve finally crumbled. Close to midnight on Monday, 24 April, he gave in to the popular will and restored the Third Parliament, asking the political parties to form a government.

Coming of age

This ‘people phenomenon’ holds larger meanings than simply the shunting aside of an active monarch. It has united a country that has been historically, socially and geographically divided. Between eight to ten million citizens were engaged in the weeks-long agitation, coming in from the fields and terraces, trekking to the roadheads, demanding loktantra, the new term for total democracy.

Perhaps the greatest gift of the People’s Movement of 2006, besides creating conditions for an end to the Maoist rebellion, is that it sets Nepali nationalism on more inclusive and solid foundations. To date, the nationalism of the modern era, together with its reliance on xenophobia and frivolous symbolism, was based on the midhill caste /ethnic identity, the Nepali language, a ‘Hindu’ monarchy, and a particular brand of hill Hinduism. Each of these elements had the consequence of excluding a large section of citizens, even whole communities.

had suggested: “…But the best

will be if the Spring of 2006

yields a people’s movement

that vanquishes Chairman

Gyanendra, at which point Nepal

can then start on the longdelayed

process of

reconstruction and

rehabilitation – and the revival

of a democracy better than

experienced between

1990 and 2002.”

Having been ushered in by citizens of all ethnicities, castes, languages, faiths, gender and regional origin, this new democracy is no longer a gift from Kathmandu’s powerful clique to the country at large. The inclusive democracy, to be crafted on the basis of the People’s Movement through the promised constituent assembly that will write a new Constitution, will at long last provide all of the people with ‘ownership’ of their country. The Nepal of the future will be a raucous, occasionally unruly, democracy. But the state will have the stability required for nation-building.

Already, the people have gained confidence from their ability to fight a despot and to define their own future vis-à-vis a nervous international community. This assurance adds to the country’s stature, and will henceforth provide it with self-assurance in the conduct of foreign relations, particularly in dealing with the overwhelming southern neighbour, India. This new confidence will translate into numerous other dividends, including more equitable development works, where the goals are set indigenously rather than by the ubiquitous ‘donor’ government or agency.

The path ahead will be necessarily bumpy, but the goal is clear: making inclusive democracy happen, righting the historical wrongs against the majority population in this country of minorities. The task began with the defeat of Gyanendra’s preposterous agenda. The kingship has been brought to its knees, which is where it will have to be kept, if it is kept at all.

Nepal needs to go back to being a country where the people smile; where villagers on the trail look at you in the eye and brightly inquire into your personal history, rather than fearfully looking away. Already, during the People’s Movement, the twinkle had returned to the Nepali eye.