From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 8 (AUG 2007)

Bistirno duparer

Ashonkho manusher

Hahakar shunye-o

Nishobdo nirobey

O Gonga tumi,

Gonga boyechho kyano

In the lyrics and music inspired by Paul Robeson’s version of “Ol’ Man River”, Bhupen Hazarika addresses the Ganga as the mighty one that flows on and on, disregarding the misery of millions along its banks. Originally sung in Assamiya and referring to the Luit, the song would allow rivers some agency, harking back to the powerful watercourse of Southasian myth and history.

But how these rivers have changed, in most parts of the Subcontinent. Having gorged on the monsoonal rains, they do get to strut for three or four months every year, but even then they are blamed for what they do naturally – ie, flood during the summer. At other times, many of our rivers are little more than sewers, and the holiness associated with the ghats and sacred ‘Ganga jal’ is not enough to motivate the environmental and cultural activists to save them.

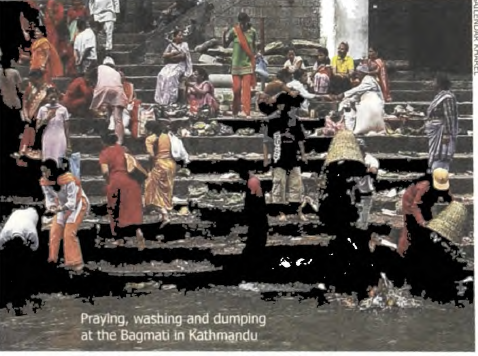

The Bagmati of Kathmandu is by now an open sewer, and only the most fundamentally minded will discount the coliform bacteria count in the Ganga at Benaras. The Ravi, by Lahore, is down to a trickle. Kabul River, like the Bagmati, is a cesspool. In Ahmedabad, the Sabarmati is sickly. The Jamuna has hardly a current any longer as it passes by Delhi, and pictures of the Taj Mahal from the riverside can be a farce.

Upstream irrigation and Delhi’s catapulting thirst for water can be blamed for reducing the Jamuna in this way. As for the Ganga, massive amounts of water are extracted along its course, particularly in Uttar Pradesh, to the extent that lower riparians Bihar and Bangladesh are cheated of their fair share. Then the Farakka Barrage diverts so much water into the Hooghly that during the dry months downstream you can walk across the Padma (Ganga) by pulling up your lungi. You call this a river? It is humanity that should now be showing concern, calling out O Gonga tumi!

The Brahmaputra, at least, glides past Guwahati in its timeless girth. There is just too much water in it for hilly upstream Assam and Arunachal to utilise. But then there comes word that, up above the famous bend in the river, before the Tsang Po plunges down to Arunachal and becomes the Brahmaputra, the Chinese are planning a diversion to water the plains of Qinghai.

The dumping of untreated urban waste and the leaching of pesticides and fertilisers mean that, even where there is a flow, Southasian waters are a cocktail of effluents and poison. Almost everywhere, the rivers are embanked in order to keep the floods in; but in so doing, local water is kept out. Meanwhile, the silt is deposited within the levees, raising the level of the riverbed. Within decades, engineers have run out of new ideas as to how to deal with the situation; and the river rises above the level of the land, inviting mass disaster should the embankments burst. On the Kosi, we are just about getting there.

Even where the rivers still surge with full flow, untrammelled by dams, reservoirs and canals, dangers loom. The warming of the globe means that the Himalayan glaciers have receded right back up the mountains, and the volume of snow and ice that come together to make the Himalayan range the ‘water tower’ of Asia is dwindling. After a period of high-altitude snowmelt, there will be nothing left to turn to water and the rivers will shrink.

Southasia’s rivers are shrivelled beings today, completely wrested of the heroic image promoted by the mythology of Robeson and Hazarika, of uncaring, all-powerful leviathans that neglect their watersheds’ populace. Instead, it is the people who have managed to convert the rivers of Southasia into such abject creatures – poisoned, embanked, drained and diverted.

Oh, Ganga! Just look at you!