From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 8 (AUG 2007)

Everyone agrees on the importance of holding Nepal’s Constituent Assembly elections on 22 November, and it’s beginning to look like we’ll get there.

There is a unique experiment in nation-state-building underway in a corner of Southasia, where a people and a country enjoy a chance given them to redefine state-society relations. While the dangers of failure do loom, there are also immense opportunities at hand: to create a polity that responds to the demands of pluralism and democracy, while also providing social inclusion amidst a demographically ultra-diverse population, where essentially everyone is a minority. The people of Nepal today have the opportunity to learn from both other Southasian experiences and those of the rest of the world, as they put behind them ten years of insurgency and a history of exploitation and Kathmandu Valley centralism. But most importantly, in drafting a new constitution – elections to a Constituent Assembly will be held on 22 November – they are being given the chance to learn from their own half-century of modern-day experience, accumulated since Nepal opened itself to the world with the end of the Rana oligarchy.

It is a privilege to be a Nepali at this hour: to be able to see and to give one’s input in the fashioning of a political system that provides space simultaneously for national and communitarian identities; and on that basis, to evolve a pluralistic democracy, which brings political stability and an economic boost at long last to the entire populace in mountain, hill and plain. Nepal, in reality the oldest country of Southasia, achieved democracy only in 1990, but is only now going about the process of ‘nation building’. That process must move the people quickly from self-awareness to articulation, activism and then to the act of drafting constitutional text. There is no way around the compressed timeframe, as there are dangers of mayhem, anarchy, foreign interference and inter-community strife if the current momentum is lost.

The eight parties in government, including the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), have now agreed on mixed-format elections. These will subsequently provide 240 seats for candidates competing in as many constituencies, and another 240 seats for the proportional ballot, where parties will have to fill the seats they win in accordance with the percentage of communities in the population, attributing proportional numbers to Janajati hill-ethnic groups, Madhesi plainspeople, Dalits, people from the neglected far west and others. Devised by a task force within the interim parliament, this mixed ballot system is a unique compromise between the demands of parliamentary governance and those of participation in the framing of a new constitution; between political ideology and identity politics; between the political parties at the helm and groups claiming to better represent the diverse communities.

There are many who believe that, for this election to a body that would formulate a constitution, the ‘full proportional’ formula should have been applied – to provide a totally inclusive assembly representing all of the country’s population groups. Most have nonetheless come to accept the mixed formula as a fait accompli, while not just a few believe that it is just right for Nepal. Given the dangers of postponing the November elections, the mood is to grasp the achievements already at hand and to lobby for more during the Constituent Assembly debates.

Few are thinking of just how the Constituent Assembly is going to function, as all attention is currently focused on actually getting to 22 November. Expected to take up to two years after November, the Assembly will provide an opportunity for the articulation of demands by myriad communities and identities, demands that will mostly be aired for the first time and have not been tested against each other. Among other things, the Assembly will ultimately decide on whether to keep a constitutional kingship (unless Gyanendra the Incumbent makes a foolish move, given which the existing interim parliament is empowered to abolish the institution altogether); what kind of affirmative action can be applied in a country full of deprived minorities; which type of federal system can best incorporate identity demands, while maintaining inter-community relationships and economic viability; the issue of language policy; whether Nepal requires a standing army at all; what kind of welfare state the country will be, and so on. But that is for later. What is required right now is to address the immediate demand of proper representation in the polls; other hurdles may be tackled further along on the way to the elections.

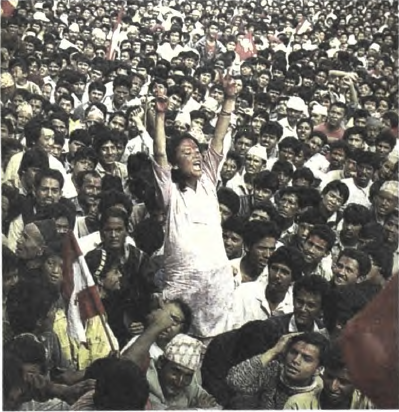

People’s Movement through this well-known picture by Min RatnaBajracharya. Bajracharya shot Thapa again on the streets of Kathmandu during the April 2006 uprising.

Roadblocks

Besides the all-important factor of lawlessness countrywide and the failure of state administration, the biggest challenge on the road to the Constituent Assembly elections is the buy-in of Janajati groups and the Madhesi community to the mixed electoral system. While more disenfranchised than even these communities, the Dalits of the hills and plains have greater justification for insisting on a proportional system; but their ability to organise and agitate has been stymied for various reasons.

The mixed electoral system – of direct and proportional ballots – now seems to be a necessity for several reasons. First and foremost, the political parties and the interim parliament in control of the polity have already decided on it. Some Janajati and Madhesi activists lobbying for a full-proportional system insist that it is “Better to have no elections than a flawed election.” However, the dangers of a failed election loom so large that most seem willing to compromise in favour of a mixed system as a bird in hand, with the hope for getting the two in the Constituent Assembly bush. Everyone other than the incorrigible rejectionists among the Janajatis and Madhesis can be brought on board through the granting of sunischita-ta, whereby the eight parties provide guarantees rather than mere assurances that the Janajati groups will have at least one representative each on the official roster of nationalities present in the Constituent Assembly, and that the Madhesi plains people will be represented in proportion to their 33.2 percent presence in the population.

The hazard of November passing without the polls is severe. The earlier deadline for elections this past June was allowed to lapse, but that did not create an insurmountable problem because the public understood the date to have been impossible in any case. However, the November tryst with the ballot box is regarded as make-or-break by the Nepali people and the international community alike. Both Girija Prasad Koirala’s interim coalition government and the self-appointed interim parliament (which superseded the earlier elected House in order to rope in the Maoists), having failed to make the June date as mandated by the interim constitution, are actually functioning within a grace period over the monsoon and the autumn of 2007. Inability to hold elections in November would take away the fig leaf of legitimacy from the government and interim parliament alike, at which point the country would enter a freefall.

The likely scenario of what would then happen runs thus. While the country presently lacks real governance, Nepal would enter a period of utter chaos, at which point the public would be ready to accept any entity that could assure a state administration. In the search for stability, the international community, including India, would support an army-backed civilian government – and, judging from past experience during the royal autocracy, there would be enough Nepali politicians and parties willing to submit themselves to the ignominy of being a part. What would result is a significant loss of the people’s sovereignty, both internally (to the military) and externally (to India and the larger world). The hopes manifested in the upsurge of the People’s Movement of April 2006 would be dashed.

The generals of the Nepal Army itself, as the allies of a king defeated by the People’s Movement, would be savouring the prospect of a comeback, riding on the hobbled horse of a failed state. The goal must be to give the generals no such satisfaction. As with Gyanendra (as yet the king), at the time of writing the Nepal Army does not actually have the ability to create roadblocks to the Constituent Assembly. The eight parties remain in command, though their unity at times appears to fray, and as long as they stand together, the generals will be kept at bay even as the poll date nears. The Nepal Army used to provide the primary logistics and security during general elections past. Though bloated in size to a lakh soldiers, it will have no function in November but to watch from the barracks, which is indeed its comeuppance.

As for Gyanendra, the man remains a potent danger and a rallying point for anarchists, royalists and ultra-conservatives alike, who would prefer a reversal from the course towards peace and democracy. He could decide to open his coffers to fund Hindu extremists, royalists and other disgruntled elements, or to infiltrate existing movements, to rock the society and obviate elections.

Fifteen months after his ignominious retreat in the face of people power, Gyanendra has yet to see a reversal of his monarchy’s fortunes, however. The Maoists, who need to distract their followers’ attention from the abandonment of the ‘people’s war’, have been clamouring publicly for the immediate creation of a republican state. This, coupled with the thick residue of suspicion for his autocratic antecedents and his continuing unwillingness to sit still (seen, for instance, in the attempt to organise a three-day bash for his birthday in early July), Gyanendra’s kingship is currently lower in the water than it was even a year ago – and is sinking fast.

In terms of getting to the November polls, more critical than fanciful royal hopes of a comeback, or even the army’s mindset, are the issues of internal security and voter education. The inability to ensure law and order and the absence of state administration have been the biggest failures of Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala and his Home Minister, Krishna Prasad Sitaula over the past year. The monsoon is generally the period when the agitations of the spring level off in Nepal, however, and the hope now is that the government will take this hoped-for lull to motivate the police force and district administrations, creating conditions for free and fair elections to be held in a country just emerging from the violence of a ten-year internal conflict.

The challenge of ballot education, meanwhile, is said to be singular – voters are asked to vote twice, once for a candidate and once for a party. That in itself would not be beyond the ken of the average voter, but the issues in the election campaign will be novel – the federal structure, affirmative action, the role of the military, the place of a transforming rebel party, and so on. While the National Election Commission and scores of NGOs are likely to attend to the needs of the voters in the months ahead, nothing educates better than political parties getting active in campaign. In Nepal, the parties now need to focus on reaching directly to the grassroots, and must not wait for the police posts to get there first. They have been very late in doing this, the representatives having become remote from their constituencies over the decade of Maoist insurgency, when it was next to impossible to visit the villages. Lately, the party leaders have at least started to arrive in the district headquarters – Nepal has 75 – but it is crucial that they now undertake sustained campaigns in the hinterland.

A people’s wish

One reason that elections are more than likely to go forward in November is simply that influential India wants them so bad. New Delhi policymakers see the Constituent Assembly polls as the only way for Nepal to achieve political stability, which New Delhi wants for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is for the opportunity to tap into Nepal’s vast hydropower potential, besides the benefit of having a secure neighbour for Uttar Pradesh and Bihar across the open international border. The rest of the international community, long involved in Nepal as development partners and having relatively little geopolitical stake, also seeks stability as a means of promoting progress in a country in such a frustrating situation – full of possibilities, but so sadly unable to fulfil them.

Within Nepal, all of the mainstream political forces want elections. Koirala’s Nepali Congress party is expected to do comparatively poorly, particularly for having lost its Tarai vote-bank to the Madhes agitation. While this might worry the ailing prime minister, he is too keen on leaving a legacy through the Constituent Assembly not to want the polls to go forward – holding the elections would cap his success in bringing the Maoists in from the cold and pushing back the royal ambitions of Gyanendra. The mainstream Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist), or CPN (UML), is also keen on the November elections because its internal surveys predict a good harvest.

And what of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist)? Most analysts predict a poor showing for the Maoists in the first-past-the-post ballots, mainly because the organisational political base of the transforming rebel party is as yet weak, such that even its most towering leaders are expected to have a hard time winning seats by themselves. However, the Maoists are expecting to make up some of this shortfall by attaining numbers in the proportional half of the elections – tapping into the underclass vote throughout the country, which will cumulatively add up to what will hopefully be a respectable sum. But this will undoubtedly still fall far short of the strength the Maoists currently enjoy in the interim parliament, which is at par with that of the Nepali Congress and the mainstream CPN (UML).

As such, it is natural for the more doctrinal among the Maoists to shy away from the possible ignominy of defeat, after its past rhetoric of ‘carrying the country’, which had quite a few foreign observers believing. Fortunately, the hold of the political-minded Maoist leadership, led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal (aka Chairman Prachanda), seems to indicate that the CPN (Maoist) would opt for long-term growth as a political party, rather than risk being an international pariah for playing the role of spoilsport. Even if the Maoist leadership is willing, however, there are dangers that the polls could still get derailed by its inability to handle its internal contradictions and the waywardness of its cadres, including in the Young Communist League. And there is always the alarming possibility that if they do poorly at the ballot, the Maoists will reject the results and put the blame on national and international conspiracies.

The Tarai violence and criminalisation could also play a role in thwarting attempts to make the November date. The Madhesi and Janajati groups alike could decide that they have not received the necessary guarantees from the political parties for proper representation of their flock in the election roster.

And yet, for all of these roadblocks and imponderables, the people’s desire for stability in an inclusive ‘new Nepal’ is expected to see through the elections – in addition to the activities of an able National Election Commission and the firm backing of India and the larger international community. Meanwhile, how free and fair the elections are will have to be seen against the prism of the three general elections held in 1991, 1994 and 1999, and some allowances must be made for a country emerging from a long decade of conflict and intimidation. Besides, the expected turnout of a little under 70 percent should allow for an extra margin of forbearance when it comes to evaluating the elections. All in all, it will be a matter of conducting polls of enough credibility that the results will not be rejected by the people of Nepal.

The people see the upcoming elections as part of the as-yet incomplete peace process, and so from villages to towns to cities, in violence-prone regions and those at relative calm, the apariharyata (necessity) of the elections is seen side by side with the chunauti (challenges) of holding it. The citizen does not have to be a jurist to recognise that the Constituent Assembly polls are an attempt to re-legitimise governance in Nepal – an attempt to provide punah-baidhanikata, or full legality – through the imprimatur of the ballot box. This is why the people of Nepal want a Constituent Assembly, to acquire a fully legitimate government in the place of today’s kaam-chalau (literally, make-do) regime, backed by an unelected parliament. As far as the Madhesi and Janajati activists are concerned, they say they want elections much more than do the nervous politicians – who fear the unknown – and that their enthusiasm will be at 100 percent once they get the guarantees of representation they seek.

Then there is the need for international election observation. The world community must reward the Nepali people for their continuing perseverance and patience, so long after the People’s Movement of April 2006, by flooding the country with election observers in the run-up to and during the elections. Indeed, the onomatopoetic Nepali word chyapchyapti describes well what is needed come November – election observers everywhere, behind every bush.

Fortunately, the task of monitoring the arms-management process prior to the elections – as well as the monitoring of the preparations for and holding of elections – has been tasked to the United Nations Mission in Nepal, a well-endowed team of 1000, including some 300 international staff. The Nepali public is looking forward to the international standards that the UN team will bring to its work, in the hope that the waywardness of the nervous Maoists ranks will be kept in check even as the state administration is held up to some standards, and the Nepal Army locked within the barracks.

Beyond 22 November

Under the arrangements that have been made, the Constituent Assembly will not only write the new Constitution, but will also function as a parliament, to choose the government that will rule the country while the Constitution of Nepal is being drafted. It is not surprising, therefore, that the political parties are already in campaign mode to maximise their showing in the Assembly, in order to form a government. Given the instability and polarisation extant in the country as it prepares for elections, and to provide stability within the Constituent Assembly, three formulae are currently important for a campaign process that is not so acrimonious that it defeats its purpose.

First, in order to ensure that the top ranks, including that of the Maoists, makes it to the Assembly, it would be advisable for the political parties to come to an arrangement among themselves whereby a handful of leaders of the ruling alliance would win without too much difficulty. This kind of arrangement, while it may be considered undemocratic at other times, is requried to moderate the level of hostilities during the campaign phase between now and November. There is a need to minimise the threats to the holding of the elections, and this would be one way. With their berth in the Assembly secure, the top leaders would also hopefully be able to campaign more magnanimously for the transformative polls than they would on competitive terrain.

Second, there should be an all-party unity government for the duration of the Constituent Assembly, as well as leading up to the first general elections. The relative stability of such a unity government would also allow the Assembly to concentrate on the task of writing a constitution. The guarantee of such a cooperative government would also, once again, lower the level of animosity and competition in the months ahead. This would also go along with the spirit of the interim constitution, which calls for a government by consensus during the Assembly, which in turn would make it possible to adopt the draft constitution unanimously.

Third, there is the view that it would make sense for the political parties to agree on a set of non-binding guiding principles before the elections, so as to ensure a general agreement on some basic tenets – such as commitment to political pluralism, human rights, social security, accountability for past atrocities, and inclusion in governance. At a time when the Maoists still prefer to talk in terms of ‘multi-party competition’ rather than democracy and pluralism, there are many who believe that these ideals must be written in stone before the elections, as basic values that would automatically be included in the new constitution. Many also want such a set of principles to include reference to a republican state – this would allow the Maoists to claim victory and puncture any remaining royalist ambitions.

When the estimated 17.5 million voters in Nepal go to the polling booths on 22 November, they will be confronted with two ballot sheets, and two ballot boxes of translucent plastic. On one ballot, they will select their choice candidate for their constituency. On the other, they will select the party they prefer. Even if the mixed system is not perfect, there will be a whole new political class that will emerge on the national landscape. From the 240 proportional seats will come representatives according to their percentage in the population; there will be Madhesis, Janajatis, Dalits and others, and fifty percent of all of these will be women. The task of civil-society activists in the days ahead will be to lobby and pressurise the political parties, such that even the 240 seats for direct elections are distributed in a way that reflects the principles of inclusion and proportion in population.

Once in the Constituent Assembly, those who get elected will be representatives who – through their skills in oration, grasp of principles and issues, ability to lobby, and sheer charisma – will wrest the leadership of their respective parties. In the last year, seminars and conferences in Kathmandu have begun to include categories of people that would never have been there a couple of years ago. Already, the rainbow spectrum is discernable in the television talk shows, the discussion programmes and the line-up of orators at mass rallies. The Constituent Assembly will consolidate this trend, and it will work towards making a country and polity that is democratic and stable. Then, at long last, the people of Nepal will be able to reap the benefits that their country had long promised but had been unable, in the absence of sustained democracy, to deliver.

What the massive People’s Movement of April 2006 demanded was peace, pluralism and inclusion, for the sake of political stability and economic progress, and the Constituent Assembly is how we will get there. What will result, nearly 240 years after the founding of the country, will be a polity that is stable and increasingly prosperous, in which the people get to reap the rewards of what their geography is capable of providing. Nepal will at long last – centuries late – be a country from which people will not have to migrate in search of menial labour. It will be a country that will do Southasia proud.