From Himal Southasian, Volume 21, Number 9 (SEP 2008)

Chauvinist nationalism is possibly the worst trait to be found in modern-day humans – which is, of course, a species that includes Southasians, even though we tend sometimes to think (as Southasian chauvinists, that is) that we are a breed apart. This chauvinism is nicely portrayed by the Indian and Pakistani establishments, which together offer the flags-lowering ceremony at the Attari-Wagah border point. There, we get to see the synchronised choreography of boot-stomping, chest-thumping, scowling soldiers in mock face-off, to the cheers and hoots of the good citizens of Pakistan and India. After the celebration, they get back to their pani poori and kebabs, meek civilians once more who have gotten their adrenalin fix, which perhaps is also an evolutionary requirement.

And yet, while it may be linked to evolution, the more exclusive the nationalism that one harbours, the more lightweight it tends to be. The Nepali militant will shout himself hoarse about the Indian grab of Kalapani at the tri-junction of India-Nepal-China/Tibet, but will tape over his mouth the moment he gets close to power in Kathmandu. Chauvinism-on-call is evident in the immediate aftermath of any bombing in any of our countries, where, rather than blame forces within, the immediate and readymade recourse is to the intelligence acronym from across the border.

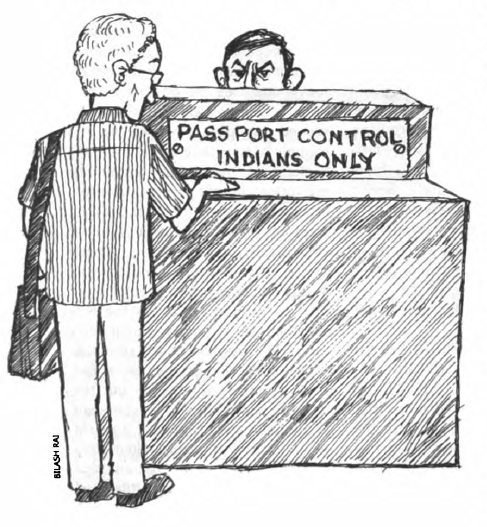

And the nationalism becomes easily dispensable at the most mundane, personal level, especially when no one is watching. Take the case of the non-Indian Southasian who lands at the Indira Gandhi International Airport in Delhi. You arrive at the immigration line, and the queue for ‘foreigners’ is a long and winding one, whereas the section for ‘Indian citizens’ is empty and attractive. An immigration officer comes forward and waves a whole bunch of you towards the empty side, ushering in a moment’s indecision: does one compromise on one’s national pride and stay in the ‘foreigners’ line for another half hour, or does one opt, for the sheer practicality of it, to get out of this claustrophobic foyer as quickly as possible? Of course, it is only a moment’s indecision. As the holder of a passport from Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh or Nepal, you will be the exception if you do not meekly sidle over. If you have any lingering nationalist guilt, you can take a surreptitious glance or two over your shoulder, just to make sure no compatriot with stouter spine is watching.

Perhaps this perfunctory and opportunistic nationalism is all for the better, if we are to think of a future of Southasia where the borders become increasingly irrelevant. Perhaps a focus on international relations (or regional relations) would suggest that what we need for Southasian solidarity, and for the Great Pushback of the Westphalian state, is to encourage ways and means to make our individual nationalisms weaker, or at least less up-front. Along this line of thought, could it be that, for the greater mass of people engaged in their roji-roti, nationalism is not really a matter of high priority? And that for the power elites it is a matter of light weight, to be jettisoned the moment the queue on the other side becomes more convenient? Extreme self-interest, this logic tells us, is the way to fight extremism in nationalism, and is the way forward to Southasian solidarity.

Now, if you will excuse me, I think I shall sidle over to this gentleman here at the counter:

“Yes sir, from Kathmandu … uh-huh, yeh Nepali passport hee hai. What? Back to the end of the other line? Aap kya baat kar rahe hain, sir ji?!”