From Himal Southasian, Volume 23, Number 5 (MAY 2010)

Even though PIA Flight 269 was bound from Kathmandu to Karachi, I was excited to visit the Sindhi Hyderabad. For too long, the Deccan city and capital of Andhra, with its IT glamour, had wrested the limelight from its humbler counterpart. Lo! Even the screen indicating the Pakistani Airbus’s flight-path showed the Deccan Hyderabad, but not the city by the Indus to which I was bound.

From the Karachi airport, ‘Haidarabad’, as it is properly pronounced, is a two-and-a-half-hour drive through the rolling desert along the M9 motorway. The city is reached after descending a plateau and crossing a rivulet – in actuality, the great River Indus in its emaciated present-day avatar. There, a traveller crosses eastward, over a bridge that seems too long for a flow this miniscule, even though it is supposed to be the consolidated flow of all six tributaries upstream. India has tapped the three eastern rivers under the auspices of the Indus River Treaty, and Pakistani Punjab takes copious draughts from the remaining three.

The inhabitants of Sindh seem impelled by the force of history to speak of their great past – the great Indus civilisation and its archaeological remains, the conquests of Iskandar, the rise of the Sindhi language, Buddhism, Sufism and the arrival of Islam. Those were the times when the Indus flowed with strength, and contrasts with a beleaguered present are unavoidable. With the river nearly gone, Sindhis seek to preserve their pride in the Ajrak block-printed shawls that are presented to visitors, and in the vibrant Sindhi press that challenges Urdu as the language of political discourse.

The Sindhi heart does seem to throb for more agency within the Punjab-dominated Pakistani state. News comes on radio and television of the Parliament in Islamabad having adopted the 18th Amendment amidst much jubilation. In ‘Haidarabad’, the Sindhi nationalists had called a closure of the city, refusing to be taken in by what they said was a fraudulent federalism. Said one activist, “All we got was the colonial spelling of ‘Sind’ changed to ‘Sindh’, just as ‘Baluchistan’ became ‘Balochistan’.” If it took six decades to add the ‘h’ and replace the ‘u’, how much longer for real federalism to come about?

Well past midnight, we travelled north along the N5 highway and arrive at Bhitshah, with its shrine of the mystic Shah Abdul Latif. Men and women mill about amidst the chanting of Sufi minstrels; the faithful taken over by sleep lie down amidst the many graves surrounding the mausoleum.

The rule appears to be: The more arid the climate, the more inhospitable the terrain, the higher the level of humanist philosophy. This is probably why the great Sufi saints lived here, nurturing their syncretistic and inclusive faith in this Sindhi-Seraiki-Punjabi strip of territory along the Indus. Wrote Shah Latif in the early 1700s, as if he had been talking of Sindh today, in this translation by the late D H Butani:

Tell me the stories, oh thorn-brush,

Of the mighty merchants of the Indus,

Of the nights and the days of the

prosperous times,

Are you in pain now, oh thorn-brush?

Because they have departed:

In protest, cease to flower.

Oh thorn-brush, how old were you

When the river was in full flood?

The river is littered with mud

And the banks grow only straws

The river has lost its old strength.

Even so, the cultural activists of Sindh hardly seem morose – theirs is an open and self-questioning attitude, with the rigidities of faith seemingly absent. They may be nationalist, but the secular bedrock of Sindhi Sufism seems to preclude chauvinism. Though these activists of ‘Haidarabad’ may seem insular in their nationalist aspirations, they are very aware that they form part of the Southasian mosaic. And it is okay to place transparent gin in mineral water bottles as you decided to let your hair down in public.

If the Subcontinent is to take advantage of its possibilities, some states and provinces will have to play more of a part than others. Sindh is likely to show the way. If it can wrest more agency from the Pakistani state, it will first ensure the advancement of the population within. But thereafter, it will point the way to the kind of Southasia we should be envisioning: a group of nation states whose provinces and states communicate, interact, trade and revive the penumbra of cultures, making us just as we used to be.

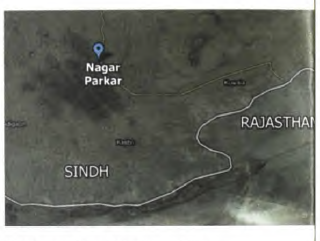

But does it make sense to talk about a federal ‘soft border’ Southasia when a fence has been put up to separate Sindh from Rajasthan and Gujarat? The hope is that this fence – and the pillboxes, searchlights and service track – will deteriorate the moment there is a better understanding across borders. For this, the units of Southasia, more than its central establishments, have to have a say.

In the Nagar Parkar desert in eastern Sindh, there is a ‘vulture restaurant’, run by the Dhartee Development Society, an NGO. The ‘restaurant’ provides clean animal carcasses for vultures, which are vulnerable to livestock that have been tainted by the drug Diclofenac, an anti-inflammation and pain-reliever drug. Nagar Parkar lies right by the Indian frontier, a stone’s throw from the India-Pakistan border fence. Rajasthani vultures know enough to overfly and alight at Nagar Parkar, to partake of the delicacies put up by the environmentalists of Sindh. Left to the Sindhis, human denizens would be able to do this too, and sooner than later.