From Himal Southasian, Volume 23, Number 10/11 (OCT/NOV 2010)

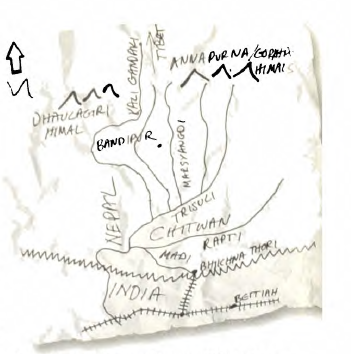

Come with me early this upcoming winter for a trip through backwater history, across borders and ecological zones, across fields, rivers, forests, gorges – and to confront the invasion of modern reality every step of the way. The trip I propose* starts in West Champaran district of Bihar, moving northward through the Chitwan jungle into the central Nepal midhills.

The British built one continuous railway line from Siliguri in North Bengal to Agra-on-Jamuna, hugging the Nepal frontier much of the way, taking in Kishanganj, Darbanga, Sitamari, Motihari, Bettiah, Gorakhpur, Balrampur and Shajahanpur. In childhood, I remember alighting with my family at the station of Dang in North Bihar, crossing the border to visit my maternal home in the village of Sisaut. My maternal ancestors had been exiled by the Kathmandu court, which is how hill Bahuns had found themselves in this corner of dehaat.

It is this memory of the choti line, the lazy khatak-khatak of small wheels on ancient rails, the open windows and the sheer ‘rurality’ of the passengers that now makes me want to train westward from Raxaul. Much of the meter gauge in this serpentine Siliguri-Agra line – run by the North-Eastern Railway component of the behemoth Indian Railways – is now giving way to broad gauge. But this section in Bihar has yet to convert. Near Raxaul is the small station of Sugauli, which also marks the place where the treaty of 1816 was signed between the Kathmandu durbar and the Company Bahadur. According to my childhood reading there used to be a pillar commemorating the event, but I could not find it the last time I passed through Champaran. (For more on West Champaran, see the article in this issue by Abhay Mohan Jha of Bettiah.)

All of the hill trails of the central Nepal hills, as well as the paths coming down from Tibet’s Changtang plateau, down past the principality of Lo Manthang, follow river valleys to end up at the mercantile hilltop township of Bandipur. In 1973, Bandipur was bypassed by the Kathmandu-Pokhara highway, which took the low road, and the district headquarters too was shifted down-valley to Damauli. This was fortunate, in retrospect, because Bandipur’s old-world Newar streetscape was preserved. The rock-slab pavements are intact, and the town has suddenly evolved into a tourist destination. Perched high above the Marsyangdi River, this lion-king settlement gives you a 300 km Himalayan panorama to the north, including the nearby ranges of Ganesh Himal, Gorkha Himal, the Annapurnas and Dhaulagiri.

Bandipur was a trading post manned by ethnic Newar sahu merchants, who sold the wares sent up from the Ganga plain. Nepal might have been a closed kingdom, but it was open to mercantilist wares from an India being overrun by the East India Company. Commerce seeped into the Himalayan capillaries through trading posts such as Bandipur.

Now, turn your back to the Himals, and your mind and body southwards. The consolidated trail becomes a robust affair with fine porter rest-stops built by philanthropist sahus. The path drops sharply to the Trisuli River, crosses it at the point of Ghumaune, where the modern highway intersects to take you swiftly downriver to the Chitwan valley. Chitwan is a doon, or inner Tarai valley, guarded by the Chure/Shivalik hills along the south. Westward, you have similar doons in Dang-Deokhuri and Dehradun.

Till the 1960s, Chitwan was a massive jungle expanse of about 400 sq miles, the place of sal (shorea robusta) and riverine woodlands and swamps, with scattered ethnic Tharu settlements, rich in rhinoceros, tiger, langur, nilgai, boar, elephant, two species of crocodile and an incredible variety of wild fowl, migratory and sedentary. The entire swath of forest is now finished off, courtesy an American-supported settlement scheme that eradicated malaria and brought down the highlanders of the central Nepal midhills. As a child, I remember the sal forests licking the sides of the aerodrome at Bharatpur, but now the rice paddies extend all the way to the Rapti River to the south.

Following the Trisuli River into the Chitwan Valley, the ancient travellers would band together to negotiate the jungle expanse. At least some of the history of this last great surviving woodland of the prehistoric Ganga plain remains today, in the form of the Chitwan National Park, across the Rapti River, also the westernmost holdout of the one-horned rhinoceros. Crossing the Rapti, one enters an enchanted world of swamps, oxbow lakes, grasslands, stands of sal and kutmero, chap, simal and badahar. Distressingly, many of these trees are today shrouded by the invasive creeper called mikranta, an unwanted tourist from Latin America that crushes the Chitwan jungle’s rich undergrowth and turns grasslands into shrouds, the trees into a creepy veil.

This trail through the jungle Chitwan was used by the Maoists of Nepal during their ‘people’s war’, as a supply route into the central Nepal midhills. As you drop down from the Chure ridgeline, there is the beautiful low-slung valley of Madi, along the Reyu stream, where too the highlander castes and ethnicities have overwhelmed the indigenous Tharu. It was in Madi that, in 2005, the Maoists triggered a blast that became the single largest killing field of innocents during Nepal’s conflict years.

Beyond this sharp reminder of a modern-day tragedy, one returns to the historical trail. The sage Balmiki is thought to have homesteaded nearby, in a reserve forest across the border in present-day Bihar. Before long, we arrive in Bhikna Thori and the international border, with the choti line just up the road.

To be updated on travel plans, ask to be placed on ‘Bhikna Thori’ mailing list at info@himalmag.comThis e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it