From HIMAL, Volume 2, Issue 3 (JUL/AUG 1989)

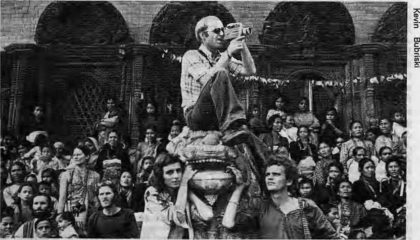

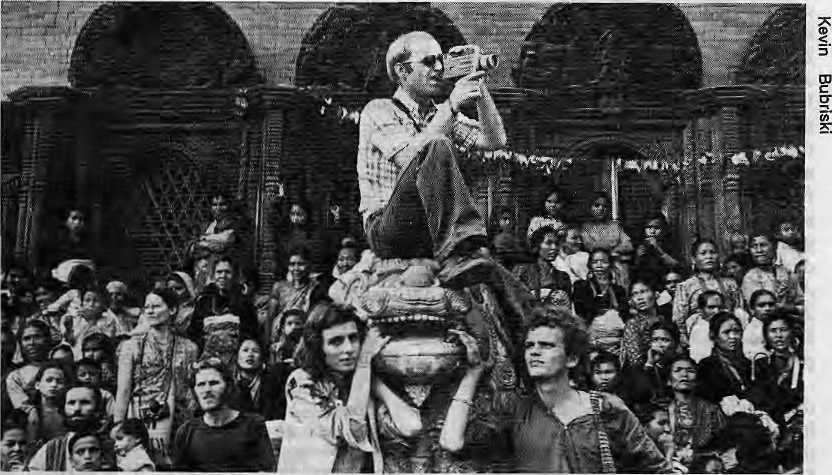

The Himalaya has taken to tourism in a big way. International visitors are swelling the high valleys from Chitral in Pakistan, eastward through Manali, Thak Khola, Khumbu, Sandakpu to Wangdiphodrang in Bhutan, They are all out to “do” Kashmir, Bhutan, Nepal or Tibet. For the foreigner, the South Asian rimland continues to attract visitors from the farthest reaches of the globe.

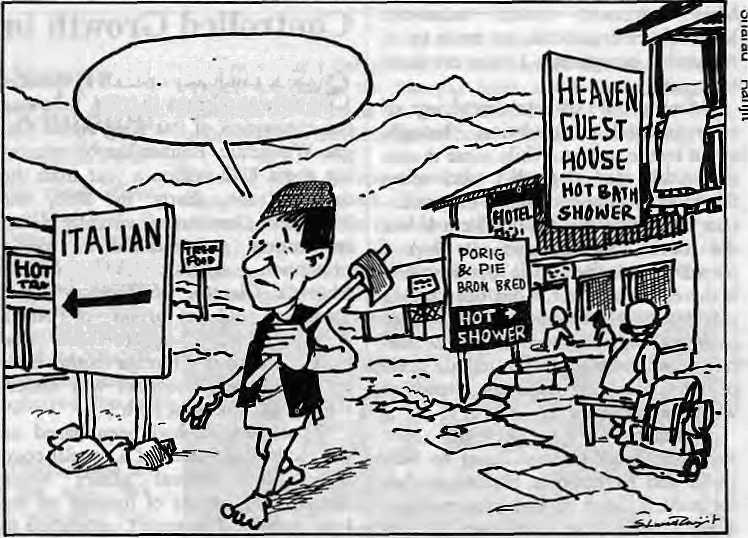

Newfound income is making its way into mountain households used to centuries of subsistence living. The economies of the region are being turned on their heads. Most would acknowledge tourism’s benefits — foreign exchange, employment, to name two ~ but the industry has always been regarded with a certain amount of discomfort, as if there were some guilt attached to it. One simplistic explanation would be that tourism brings too much too soon to too few. Tourism is categorised as an industry, but it produces no wares. In the Himalaya, tourism is the tantalising lifting of a veil – and collecting “tax” from all those who get lured by the charm. Just as the charm is lost when a veil is lifted too often, mass tourism dilutes a society’s identity.

Since tourism in the, Himalaya cannot be wished away even by those who regard it with distaste, the key is to learn to manage it as a long-term resource. It is a complex game to play and the industry is nothing if not vulnerable — to war, scarcity, internal strife and even, as in Nepal’s ongoing case, trade disputes with neighbours. Vacationers run shy at the first whiff of instability, sending the arrival charts dipping like an aircraft that has lost power.

While tourism brings precious foreign exchange to the national coffers, it also causes inflation and distorts the local economy. Even the foreign exchange that is earned often takes flight in the form of “leakages” — legal and illegal transactions that transfer hard currencies right back to where they come from.

Then, there is the question of pollution, both environmental and cultural. From non-biodegradable tourist refuse outside Tengpoche monastery, to the changing mores of Srinagar’s youth, and drug addiction in Kathmandu, all are ascribed to some degree to the opening up to tourism and outside influence. The presence of affluent foreigners in the midst of materially poor Himalayan societies gives rise to unrealistic expectations that are typically unmet. This creates maladjustments, particularly among the impressionable young.

And yet, in a region with so little in natural resources, the scenery, the people and traditions have become most valuable assets. As American geographer Nigel J.R. Allan says, speaking of the Himalaya, “Trading of some of the cultural peculiarities for basic needs is a worthwhile endeavor.” So there is no alternative to tourism — indeed, it may well be a boon. Until the Himalaya gets eroded to little hillocks, or unless there is total global economic collapse, it seems, the tourists will keep coming, and in even larger numbers. The planners, and the people, can only learn to cope with tourism and maximise the particular “comparative advantage” that all mountain regions enjoy vis-a-vis the plains. And they must do so without losing grasp of what makes the Himalaya unique in the first place.

BOOM PERIOD AHEAD

In general, the region’s hoteliers and travel agents need not worry that the tourist sport will dry up. The economic forecast is for sustained tourism growth globally as well as for the region. The World Tourism Organisation and the International Labour Organisation and most institutions and experts are bullish about prospects till century-end and beyond. Last year, Nepal, which receives 200,000-plus tourists per year, set a target of one million tourists arrivals by the turn of century. That target may turn out to be- rash, not because the potential tourists are not there but because facilities to host a million visitors will hardly be in place a decade from now, The United Nations estimates that tourism earned the Third World about U$55 billion in 1988, which makes it the developing countries’ biggest export after oil (U$70 billion annually). International tourism is expected to grow about five percent every year for the rest of the century.

There were a mere 25 million tourists traveling internationally hi 1950, but today there are about 400 million. The ILO’s Hotel and Tourism Branch estimates that there could be up to 600 million tourists girdling the globe by 2000. Where will they go? A significant and growing number will head up the Himalayan valleys. Those traipsing about in these mountains will include the “baby boomers” of the United States and Western Europe, who will soon be reaching retirement age. In 1910, Japan is expected to send 10 million tourists a year to travel the world. The newly industrialized countries in South-East Asia, as well as Australia, New Zealand, and glasnost-bitten Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, are all prospective markets.

In South Asia, the ever-growing Indian middle class forms a huge and lucrative tourist market all its own. In the hill stations from Mahabalipuram to Darjeeling, these nouveau riche travelers are swamping the hilly lanes. Except for this year’s fiasco, Kathmandu is almost entirely reliant upon Indian tourists to fill up the hotel rooms in the summer.

EACH COUNTRY TO ITSELF

Local and national responses to tourism differ, says geographer Allan, who has written on the impact of tourism on South Asian mountain culture. The range, he says, “is from the active positive response in Nepal and Tibet, through favourable but less enthusiastic response in India, to silent acceptance in Pakistan, and aggressive reaction to foreign cultural intrusion in Afghanistan.”

Indeed, Himalayan tourism is not monolithic. Just as destinations differ from the Tarai jungles to the Mahabharat valleys to alpine highlands and trans-Himalayan drylands, each country

too has its own way of running the industry. Policies change, and an elementof schizophrenia is inevitable in an industry which requires inviting the outsider to |the inner sanctum of one’s

society and culture. Last year, Bhutan decided to restrict tourists to 2,400 a year. But in the next instant it bought an 80 seater jet that flies between Bangkok, Delhi and Kathmandu. Those seats have to be filled, and so to tourists they may turn.

Even the military rulers of xenophobic Burma (now “the Union of Myanmar”) have decided they can no longer do without turodollars. Looking enviously across the border at Thailand, which last year hosted 4.2 million visitors compared to their own 10,000, the Burmese have decided to give tourism high priority. But they are far from then- goal of 150,000 tourists by 1993.

To some, Nepal’s announced goal of one million visitors by 2000 is equally laughable. After all, lack of foresight and planning has marked Nepal’s tourism policy. In fact, it is tourism that leads the Nepali economy by the nose-string rather than the other way around. As Abid Hussain, Member of India’s National Planning Commission, stated in a lecture in New Delhi last February, “tourism-led growth rather than development-led tourism has characterised places like Jamaica, Kenya and Nepal.” In the absence of governmental action, in Nepal, the industry is led almost entirely by the private sector. In fact while the Nepali tour operators might have a thing or two to learn about managing mass tourism, they are well ahead in trekking, mountaineering and river rafting — the Himalaya’s quintessential attractions. It is these selling points that have made Nepal a primary destination for many tourists.

So far, Nepal has been fortunate in drawing the number of visitors it does without aggressive or deliberate marketing. A July 1989 report of the Tourism Study Project Office of the Nepal Rastra Bank welcomes tourism as “a major growth sector and stable sources of foreign exchange with immense potential and virtually unlimited scope.” Indeed the last 15 years has seen a three-fold increase in tourist arrivals and a 10-fold increase in gross foreign exchange receipts.

WHICH WAY TO SHANGRILA?

While Nepal’s policy is to take in whoever knocks at its doors, rich tourists or poor, Bhutan, has decided to maintain its low volume, high yield tourism. Group tourists are taken on strict itineraries at about U$200 per person per day. With a relatively unspoiled environment, low population density, and a “manageable” polity, Bhutan has been able so far to maintain this excluvist approach. But then Bhutan’s tourism is still in its infancy, having begun only 15 years ago, at the time of HM King Jigme Singhe Wangchuk’s coronation.

In fact, the Dragon Kingdom is today where Nepal was in 1955, at the time of late HM King Mahendra’s coronation. Nepal was then the “Shangrila” tour operators were searching for. Today it is Bhutan, and the mantle might have already passed on to Tibet but for the unrest that led to the imposition of martial law in February this year. Tibet is in every sense the new frontier, with the Chinese authorities having shown every inclination to promote tourism. The land is vast, with unlimited attractions for the traveler.

In South Asia, India’s tourism is bigger than all the others combined, but except for Srinagar Valley, tourism in its Himalayan region is still relatively undeveloped. Even on a national scale, it comes as a surprise to learn that the whole country hosts no more than 1,5 million tourists a year. “An annual foreign exchange of IRs 2,000 crore is nothing to feel proud about considering our potential,” says Abid Husain.

While the potential might be untapped, Indian Himalayan tourism may be the most organised, with heavy government involvement. Also, international hotel chains, and “super-travel agencies” with headquarters in Delhi or Bombay have professional planning capabilities, promotional budgets and a worldwide reach. Large sums have been injected into tourism promotion and planning under the broad umbrella of the India Tourism Development Corporation (ITDC). In Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir, state-run tourism development entities plan and implement, albeit sometimes poorly, tourism development programmes, from organised pilgrimages to ski runs, bus transports, lodges, hotels and golf courses.

MANAGING THE INDUSTRY

The Economist (March 1989) stated that Third World governments “do not use the information now plentifully available about how (tourism) works so as to make the most of it…they do not know how to grease the wheels of tourism.” This is especially true for the Himalayan region. “Take a look at Nepal’s one million target. There is no plan there. How can you declare a policy without stating how you are going to get there?” asks Veit Burger, an Austrian who in 1978 wrote an oft-quoted Ph.D. thesis on Nepali tourism. “You have to look at tourism as an export business, none of this stuff about it being an international passport to peace.”

The Sri Lankan government perhaps best understood Burger’s point. Its approach to tourism development was pragmatic and flexible, providing operators with incentives and tourists a hassle-free vacation. The government worked hand in hand with the private sector to bring in high volume tourist traffic, particularly from West Germany, But that was all before the ethnic turmoil and violence of the last few years. Arrivals plummeted to nearly half between 1982 and 1986. One fallout was the suspension of the Himalayan link to Sri Lanka, Royal Nepal Airlines’ Kathmandu-Colombo flight.

THE STATE CORPORATIONS

None of the Himalayan nations and states have been able to emulate Sri Lanka’s success at promoting mass tourism. Among the best run are the state tourism development corporations of Jammu and Kashmir and Himacha) Pradesh. They have a faster “reaction time” when crisis hit the industry, and do not shy from launching extensive media campaigns.

But HP. Tourism and J&K Tourism are all bluster and little substance, charges a Delhi travel analyst. Says the critic: “For all the slick ads and tourism seminars, they have done little to build up adequate facilities. For example they did a big sell on Sirmour lake in H.P., but the deluxe bungalows are all reserved for VIPs.”

In the Uttar Pradesh hills, poor cousins of H.P. and J&K Tourism, are two entities known as the Garhwal and Kumaon Mandal Vikas Nigams. Originally mandated to bring all-round development to then” economically depressed areas, these corporations have become largely tourism promotion projects. And they are not doing too well at that, either. Says the Delhi travel analyst, “GMVN became a tourism agency because it is easy money for little work. You do not have to invest in people and the community. Just put up garish pink and blue bungalows, buy a few buses and hire drivers: you’re in business.”

Last year, a GMVN programme to develop the area around Gangotri was shot down by sants and sadhus. Lately, an effort to develop the village of Auli into a ski resort has come under fire of environmentalists and development experts (Nov/Dec 1988 Himaf). S. Chandrakala, who has done research on tourism’s effect on the environment hi India’s resort locations, says that tourism “has meant direct devastation” in Kumaon and Garhwal. Sunil Roy, a former Director of ITDC, describes the activities of the state cooperations as “generally disastrous” because “they have a very narrow development focus and are concerned only with numbers of tourists. Whereas quality rather than quantity is important, because with lesser numbers you can earn more, with less infrastructure.”

T.V. Singh, a scholar who has written extensively on tourism issues, has this to say about efforts of the corporations: “Ad hoc and impulsive planning, indifference to research, seems to characterize most of tourism development in the Indian Himalaya.”

BASKET CASE TOURISM

Singh gives Nepal high marks. “Nepal has adopted corrective measures through appropriate research,” he says. “Efforts have been made to understand the complex phenomenon and attempt an integrated development of tourism,”

Few experts share Singh’s appreciation of Nepali efforts. In fact, they see Nepal as coming closest to the u. P. hills when it comes to tourism management ~ or the lack of it.

Tourism is already the mainstay of the Nepali economy and is central to all future calculations. Yet there is assiduous neglect of the industry. There is apathy in most areas, from tolerance of the filth in the major trekking trails to turning a bund eye to large-scale flight of foreign exchange earned from tourism.

Although Nepal has made strides toward becoming an independent travel destination, helped by alternate gateways where there was once only New Delhi, the country still depends largely on Indian agents’ marketing and sales for a significant portion of its arrivals.

By and large, the country has been thriving on its natural appeal. The Nepali government’s tourism promotion remains minuscule compared to the importance of the foreign exchange earnings from tourism, not to mention its contribution to employment. What promotion there is of Nepal abroad is done with the meagre resources of individual operators.Perhaps the case of Lumbini best highlights the apathy that pervades tourism management hi Nepal. After more than two decades following United Nations Secretary-General U Thant’s tears when he found the Buddha’s birthplace in a state of neglect, Lumbini remains an unshining example. Trees have finally begun to green the area, but facilities are virtually non-existent. Leave alone tourists, only the highly motivated pilgrim will go to Lumbini.

Contrast Lumbini’s case with the well-packaged rail-cum-road tours organised by Indian operators to the other places associated with the Sakyamuni’s life in UP and Bihar, all of them remarkably well maintained. And further progress is promised – in a new master plan by the Indian Department of Tourism to improve existing facilities, helped by a IRslOO crores soft loan from Japan.Having learnt from their mistakes, Nepalis are ahead of others in some areas. In the Annapurna Sanctuary, for example, a unique park management programme is underway which is assisting the local people to take advantage of the presence of trek-kers, while at the same time preserving, if not upgrading, the natural environ-ment.There are other signs that the Nepali government is awakening to the need to support the tourist industry. A tentative plan exists to establitablish a Tourism Development Fund and start active promotion abroad. Finally heeding the demands of the trade, the Government has gone for a limited “open skies” policy and today passengers direct from Frankfurt, Karachi, Singapore and Hong Kong disembark in Kathmandu’s newly inaugurated terminal building. Finally heeding the clamour for new trekking areas, the authorities opened the Kanchenjunga area in October 1988, and the lower reaches of the trans-Dhaulagjri region of Dolpo in May this year.

Perhaps the Government’s change of heart is best illustrated by the fact that, even while the rest of Kathmandu reeled under fuel shortages during the ongoing Indo-Nepal fireworks, the tour operators were assured of gasoline and diesel for their excursion buses. “If one good thing has come out of this trade dispute, it is that the governmenthas come to realise the importance of tourism and seems willing to support us,” says Yogendra Shakya of Marco Polo Travels.

A VULNERABLE PROPOSITION

Total reliance on tourism can be dangerous because international travelers are by and large a nervous lot. Little things deter tourists. An article in the New York Times Sunday Travel Supplement in 1988 February, detailing the medical hazards of trekking in Nepal – from diarrhea to meningitis -must have discouraged hundreds of trekkers. One isolated disappearance on the trail, and trekking will suddenly be termed “dangerous.” As soon as the Kath-mandu-Delhi crisis began, many embassies in Kathmandu sent out travel advisories warning their nationals to scrap travel plans.

Tourism is thus inherently vulnerable to the vissictitudes of geopolitics. Kathmandu hotels had been looking forward to a summer that would bring tens of thousands Indian tourists attracted by the “Hong Kong” shops, and thousands more westerners stopping over on their way to or back from Lhasa. The Indian visitors, plus the Lhasa connection, was getting to be significant enough to rescue Nepal from its “seasonal” doldrums. The unrest and martial law in Tibet, and the problems with India, quickly ended that expectation, at least temporarily.

For the moment, Kathmandu tour operators are putting on a brave face and maintaining that the main tourist season, which starts in mid-September will be as strong as ever — if the Indo-Nepal dispute is resolved by then. If not, the ruined season of 1988-89 season will cast its shadow far into the future.

Though Kathmandu hoteliers and travel agents report healthy bookings for the fall, as one agent put it: “The real test is August-end, when the advance payments have to be made. That is when the cancellations begin.”

Citing Nepal as the prime example, some experts say it is wrong for planners to develop tourism to a saturation point. Harka Gurung, a Nepali geographer and Minister of Tourism from 1976 to 1978, does not agree. He believes that no one can plan for wars and unrest, and significant income will be lost if a deliberate policy of pulling back on tourism is adopted. Tourism is not unique in being vulnerable to political turbulence, he says. A well-managed and flexible tourism policy can today cope better today with potential disasters.

ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS

Much has been made of the dangers of letting tourists have the run of the land, especially if the land is as environmentally fragile as is the Himalaya. The mountain trails frequented by the 50,000 tourists who come to trek every year are invariably littered with garbage (Mar/Apr 1989 Himal). Trekking has led to deforestation of whole tracts of upland woodlands in the Khumbu and in central Nepal.

Tourist traffic in Nainital has grown from 50,000 in 1979 to 1.5 lakh today, with over 80 new hotels in place. The resort’s famous lake is silted over, and heavily contaminated. In Srinagar, Dal Lake is dying slowly due to sewage and grime in its water. The most important pollutants, says S. Chandrakala, are the 1,000 tourist houseboats which flush wastes directly into the water, raising bacteria and coliform to extreme levels. The central government recently approved the conversion of a city forest designated as a national park into a golf course, in order to attract more tourists.

T.V. Singh is unequivocal about the environmental hazards of tourism. According to him, “Tourism and environment are generally in disagreement.Mass movement erodes massively. Mouatain environments are made up of vulnerable ecosystems. Losses are hard to repair.”

Many people dispute this charge of environmental degradation brought about by the tourist. While some mountain trails are degraded and more firewood is chopped along the mountain trails, they say the problem is not the tourist, but management. Says a Nepali trek leader, “The deforestation is there, but most of it has been taking place without the tourists. You can go to remote valleys where no tourist ventures, and yet you see the telltale scars of landslides and hillsides wiped of whole vegetation.”

Edmund Hillary, presently New Zealand’s High Commissioner to New Delhi and Kathmandu, blames tourists for making the environment worse than it would otherwise have been. He expressed a strong indictment of the industry when he spoke before an adventure travel conference in Kathmandu earlier this year. He said, “It is 38 years now since I first visited Nepal and I have developed a deep affection for the country and its people. And yet in all honesty I have to admit that there are few places where tourism has been so gravely abused. Impelled by a relentless urge for financial gain, tourism has been encouraged far beyond the ability of the country to absorb it. Forests have been denuded, tracks have been covered with litter, mountains cluttered up with leftover junk.”

CULTURAL POLLUTION

Acculturation, or “apeing” the values of another society, is another perhaps unavoidable result of welcoming tourists, and parts of the Himalayan region have been reeling under it for many years now. Few will argue that exposure to foreign visitors is entirely negative. To join modern society, some might even say that such exposure is essential to enable the people of the Himalaya to join the 20th century. Such as in the town of Bhaktapur, where tourism has revived dying arts and crafts. But, ultimately, “bad culture drives out good”. Already, people have said that Kathmandu is “a less friendly place” because of tourist overdose.

The worst case scenario of tourism’s negative impact in the Himalaya-Hindu Kush was probably of Afghanistan, ernisation and modernisation.” Besides the inflow of tourists, the process is also propelled along by international aid and its associated personnel, video movies from Bombay and overseas, the antics of the westernised local elites in the major towns, and a plethora of other agents and items of influence.

Geographer Gurung regards all the talk of cultural pollution without sentimentalism. In his view, tourism — and the larger forces of Westernisation ~ are inevitable and there are no options available, especially for Nepal. “You cannot get something without giving something up, in this case culture,” he says. “The strategy is to maximise contact so that you develop immunity to the outside culture.” Gurung believes that since the country cannot do without the income from tourism, there is “no use beating one’s chest about cultural dislocation.”

IS THERE A THRESHOLD?

Should there be a threshold figure beyond which the gates to travelers must be shut? The majority of experts say yes. There is an environmental limit beyond which an alpine valley cannot take more tourists. The Mani Rimdu festival of the Sherpas would no longer be Mani Rimdu if there are more tourists than Sherpas attending. That point might well have been reached in Tengpoche, according to recent reports.

Bhutan appears to have embraced the concept of threshold tourism and put a cap on the numbers. Suneetha Dasappa reports that a section of the Leh’s population also wanted to do the same and had forwarded to Srinagar a proposal for restricted tourism, but that it had been turned down by the state government.

Gurung believes that Nepal cannot and should not put a limit on the number of arrivals. A limit is useful for a country that has a choice, according to Tiinr “If you have other resources to tap, then why bother with tourism at all. From Bhutan’s calculation, for example, tourism is not a high priority. The Chukha hydro project can now pay for anything the country desires. So it can afford to bring down the number of foreigners seeking entry,”

Gurung points out that the Swiss and Austrians have never felt the need to limit the number of tourists coming in. And Spain annually hosts 40 million visitors. “Tourism is an economic commodity. The more you have, the more the suppliers will be able to refine then-services and expand profits,” he says.

OPTIONS AHEAD

The question of opening up restricted areas such as Larkya Bhot and Walangchung Gola in Nepal, presents the tourism planner with an unwelcome task. Some would advise that the closed off areas be maintained as such. On the other hand, if the Bhotiya people in Walangchung Gola want to reap the “decadent” benefits of tourism just the same as their neighbours in the Khum-bu, are policy-makers in Kathmandu right to deny them their wish?

Such are the complexities that face the public and the planner. Given a choice, and adequate information, people tend to make the best decisions for themselves. The government, for its part, must assist the population in reaping tourism’s long term advantages while at the same time trying to ensure that the uniqueness of the Himalaya is not irrevocably despoiled.

First and foremost, the issue is one of equity. Tourism’s largesse must not be disproportionately claimed by the city elites or siphoned off to outside interests. Tourism officials and travel operators from across the South Asian rimland must meet to exchange notes, ideas, and learn from each other. After all, tourism activities in the regions of the Himalaya, from Hunza to Khumbu to Paro Valley, have more in common with each other than with Goa or the Sundarbans. Above all, tourism planners in the Himalaya must look to integrate tourism development with other aspects of development. For that is the whole idea.

Tomorrow more than today, tourism will be a vital source of income for the impoverished mountain peoples. How to make tourism a profitable proposition, benefiting the maximum number of the Himalayan people without losing the “soul” of each individual Himalayan society is the big question. The answer depends, ultimately, upon the sense of responsibility of the travel trade, the sobriety of the visitors themselves, the cultural resilience of the Himalayan peoples, and the level-headedness and foresight of the governments that rule over them.