From Himal Southasian, Volume 13, Number 3 (MAR 2000)

CARAVAN

A film by Eric Valli

Cinemascope, 104 min

In these days of cinematic Himalayan hype it is natural to be sceptical about yet another celluloid offering on the ´exotic´ Shangri Laesque communities and landscapes of the Tibetan plateau and surrounding areas. It is therefore a pleasant surprise to find in Eric Valli´s Caravan a movie with a story, simply and powerfully told.

Eric Valli is a photographer-adventurer now turned cinematographer who before this has ventured into deep (sometimes officially forbidden) Himalayan valleys to come away with little photographic fables, such as on the “honey hunters” of the Gurung heartland of central Nepal. This time around, Valli has teamed up with Galatee Films of Paris to produce a feature film on the salt traders of the Tibetan rimland of Dolpo, in northewest Nepal.

The obvious reason for the film´s success is the director´s attention to the story-line, on which the locale and customs of Upper Dolpo then become natural appendages. In most of the Himalayan films made for Western audiences, such as the widescreen Imax presentation Everest, or even Bernardo Bertolucci´s The Little Buddha, it has tended to be the other way around.

Thinley is a tradition-bound village chieftain past his prime, who has led yak caravans over the dangerous high passes that lead down to the rongba (lowlander) country of midhill Nepal, continuing a centuries-old tradition of exchanging salt for grain. His son, Lhakpa, who was expected to take over the reins of village leadership, dies in an accident. As far as most of the villagers are concerned, Lhakpa´s friend, the proud and handsome Karma, is the natural choice to lead the next caravan to the south, although Thinley has his misgivings.

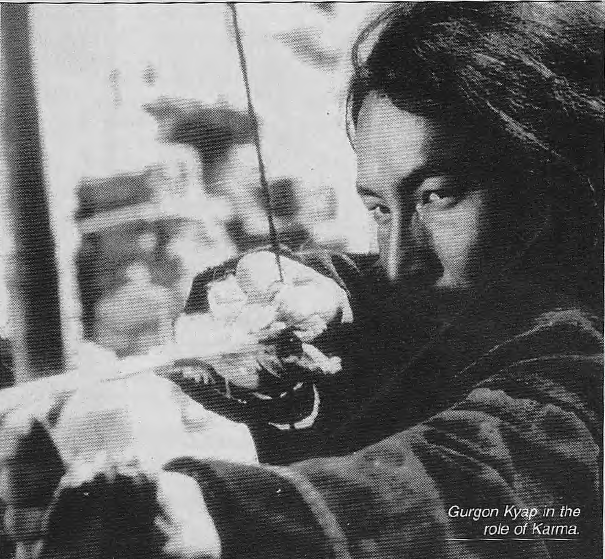

In Karma, we have the impatient modern-day non-believer. He rounds up the village youth and starts the caravan journey south before the village seer´s auspicious hour. This does not go well with the equally proud Thinley, who opts out and forms his own group which will follow the oracle, and the dictates of age-old belief, even though neither he nor his lead yak Nygimpo are any longer their youthful selves. The story of Caravan is founded on the tension that swirls around Thinley and Karma, as the two lead their followers and families separately on the perilous trans-Himlayan journey.

After a slightly awkward beginning, the film settles down to a comfortable pace with creditable performances by the non-professional actors assembled by Valli. All but three characters in the film are Dolpopa proper, including Thinley Lhondup who plays the old man and Karma Wangel in the role of his boy-grandson.

Caravan was filmed entirely ´on location´ between September 1997 and July 1998, taking all of nine months in Dolpo´s challenging terrain. The absence of elaborate studio sets enhances the film´s authentic feel, although the shooting of some of the scenes must have been difficult indeed.

Among the many outstanding episodes, and obviously a high point for Himalayan cinema, is where darkness slowly overtakes Thinley´s caravan on a high pass in the middle of a heavy snow-blizzard. This section is followed by the morning-after brightness at the latoh (pyramid of stone offerings at a pass), where Thinley finally departs with his soul.

While resisting the temptation of providing an ethnographic documtary evidence, Caravan is nevertheless successful in presenting the natural rhythms of the Dolpopas´ life-cycle through the fictional script. The various episodes are full of understatement, which requires some alertness on the part of the viewer. This is evident, for example, in the low-key acting by the ´heroine´ of the film, the Dharamsala-based Lhakpa Tsamchoe. The complexity of Thinley´s character, a loudmouth egotist and yet a man with the wisdom of the old and undoubted strength of character, is captured well. Neither the few moments of humour in the film, nor the longer episodes showing high drama or pathos, is overdone.

The authenticity of Caravan is enhanced by scenes such as the one where a bag of salt is lifted from the padded back of a yak in a gathering snowstorm —the brightness of the rug underneath is suddenly seen in contrast to the grey sprinkling of snow on the yak´s back. The “skyburial” of Lhakpa´s mortal remains is shot tastefully, with the lammergeier and griffon vultures dipping below the frame as they set about their business. The insides of window-less Dolpo houses, nighttime within yak-hair tents, and the interiors of monasteries are effectively filmed without intrusive artificial lighting. The craggy yet desert-like vistas of upper Dolpo, high passes looking across to the Himalayan ramparts, and the dark figures of yaks against snowfields, are images that one would of course expect in a film shot on the Tibetan plateau. And yet, these shots sustain, rather than detract from the story line of Caravan.

The script, written with the assistance of Olivier Dazat, has been sensitively prepared (“He saw the storm in the blue sky and I saw nothing,” laments a wiser Karma after Thinley´s death.). And again, the film seems to achieve a fair degree of ethnological authenticity despite the obvious compromises of fictional film production. The music, a mix of traditional Tibetan vocals with Western accompaniment (including the Bulgarian Symphony Orchestra) also fits in with the unfolding story.

Caravan is effective Himalayan cinema, and comes off better than the only other film this reviewer has seen in this genre, which is the somewhat surreal, The Horse Thief of 1986, based in Tibet, and directed by the Chinese Tian Zhuang-zhuang. Through its more nuanced presentation, Valli´s film is bound to enchant viewers worldwide, but it will also generate better understanding of the harsh livelihoods in the hidden valleys of the Himalayan rimland.

It is ironic that the very week that Caravan premiered in Kathmandu, Unicef and the government began an advertising blitz in their ongoing campaign to fight goitre and cretinism with iodised salt in the kingdom. Powdered salt, imported from the coast of Gujarat rather than the salt pans of Tibet, are seen as the best medium to spread iodine throughout the population. Indeed, the subsidised spread of iodised Indian salt for the sake of Nepali public health is one of several reasons that the salt caravans of Dolpo themselves are a dying tradition. And its eventual disappearance is what seems to have impelled Eric Valli to document this unique kind of trans-Himalayan trade.

Director Valli has said that the life of the Dolpopa does not have to be romanticised, and so he does not pander to the overseas viewer by hyping the romance of high plateau. “This film is a sort of a western, a Tibetan western, ” says Valli. He adds, “This saga of power, pride and glory might have taken place, just as well, in the seas of Japan, in the Normandy plains, or deep in Texas.” Fortunately for us of the Himalaya, it takes place in Dolpo.

(Earlier published in Nepali in Himalaya Times, Kathmandu.)

Joining the Oscar caravan

IS IT great news for Nepali cinema or is it Nepal´s tourism industry that shall gain? An Oscar nomination for best foreign-language film for Caravan, and maybe the award itself when it is announced on 26 March, might indeed be just reward for a challenging film, but can it truly, as the Oscar nomination does, be called “Nepal´s first Academy Award nomination”?

Not really. Of course, almost all the actors in the film are Nepali, the credits call it a “co-production of National Studio, Nepal” and mentions well-known Nepali cinema man, Neer Shah, as one among the six associate producers (as well as the names of some Nepali technical hands), but still it is an out and out foreign production headed by French director, Eric Valli. For those yet wanting to prove the Nepaliness of the movie, you could say that it was the Kathmanduphile Desmond Doig who gave Valli his first break.

Such nitpicking aside, the fact that Caravan has been running since 10 October 1999 in Kathmandu to a packed house of expats, tourists and locals, must mean that Nepali cinegoers have it in them to appreciate good cinema, however spoilt they have been by Hindi films and their poor Nepali imitations. By setting a standard for compelling cinema, Valli´s film should be able to inspire Kollywood´s filmmakers to get out of the rut of parodically copying Bollywood.