From Himal Southasian, Volume 22, Number 12 (DEC 2009)

We had to wait till 2009 before someone thought of knitting a song around the ubiquitous sound, dhantaran! This ‘expression’ does not have a Southasian origin as far as I am able to make out. Its provenance must instead lie in sound effects developed to indicate a dramatic turn of events on the silver screen. Perhaps the live accompaniment to silent film started it; but with the advent of magnetic sound there was no looking back in the manipulative use of audio to supplement the moving image.

The question is, how and why specifically dhantaran? The noise-of-choice of film directors and sound recordists surely has been a subject of research by someone, somewhere. It must have been experimentation of several years that showed that this particular phrase and sound, with its immediacy and tonality, was what was required to generate adrenalin in the sedentary cinema audience. American flicks used it with abandon, and soon Lahore was incorporating it, and Bombay continued the tradition.

What the Bombay director Vishal Bharadwaj has done is to hold up dhantaran – a sound rather than an articulated thought in word(s) – as itself a subject of scrutiny. He has crafted a song and sequence that is central to the dark film Kaminey, the late-summer hit of 2009. The lyrics are by the incredible Gulzar, and it is delivered as a disco number belted out by actor Shahid Kapoor and one other (the actual voices are of Sukhwinder Singh and Vishal Dadlani). What I have written here as dhantaran, the film’s literature spells as dhan ta nan but to each his own.

You could say that there is hardly a need to go into raptures over a mere sound in a film, but there are many aspects to the study of dhantaran. To begin with, how inadequate is the English language and Roman script to translate the full onomatopoeic strength of the expression. I have never heard, say, a native English speaker render dhantaran like a Southasian would in real life. The rendition, if ever done, would be a wooden repetition rather than the uninhibited sound-making that we hereabouts engage in.

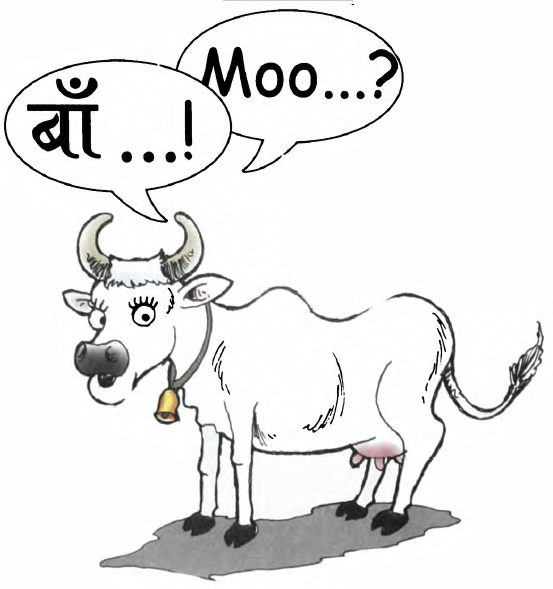

The English language does similarly struggle in other instances of onomatopoeia, suggesting for example that a cock crows with a cock-a-doodle-doo, that too in a mono-tonal interpretation. Whereas the Southasian Nepali rendition (for one) rings much more true with, kukhuri-kaaan, emanating from the human throat as would the cock’s crow at dawn. American and British cows, likewise, are locked into the perfunctory moo, whereas their Nepali counterparts as interpreted by humans go baaan. The inadequacy is not only in how you say it but how you write it. Writing in Roman, the true cross-tonal variation of the Nepali version of the cock-crow or bovine-moo cannot be presented with accuracy, including the rising timbre and nasalisation towards the end in the case of both. You will just have to ask a Nepali speaker (avian, bovine or human) to say it out loud the next time you meet one.

Some would suggest that a tongue rich in onomatopoeia is actually a poor language because of its need to rely on sound rather than a description or reference. One could perhaps beg to differ without being a linguist. Take the sound of water – as light rain, a torrent, a rivulet, or in a river gorge. Could one call a language deficient when it is able to describe light rain as sim-sim, whereas pitter-patter is more limited for it describes not the rain category but the sound of droplets hitting a roof or shingle? Or the gad-gad of a river in spate, the tup-tup of drops and drips from a receding squall, the dhararara of a tap nozzle emptying unto an already-full pail, the swain-swain (nasalised) of a river’s noise that ebbs and flows with the wind.

Back to the world of film, and how it has impacted our language. Dhantaran (nasalised at the end) is now a part of spoken Southasian. The same way celluloid gave us dhishum, the universal sound of a fist finding its mark. Is not badyang with an accompanying exclamation mark evocative of a bomb blast? Some would say that bang-bang is an adequate-enough onomatopoeia to indicate a firing pistol or rifle, but even English sees the need for the actual sound. But to describe the sound of a machine gun as heard in a trench, is the English rat-tat-tat better than dad-dad-dad, with the heavily rendered ‘d’? You decide!