From HIMAL, Volume 1, Issue 2 (NOV/DEC 1988)

By Sudhindra Sharraa and Kanak Mani Dixit

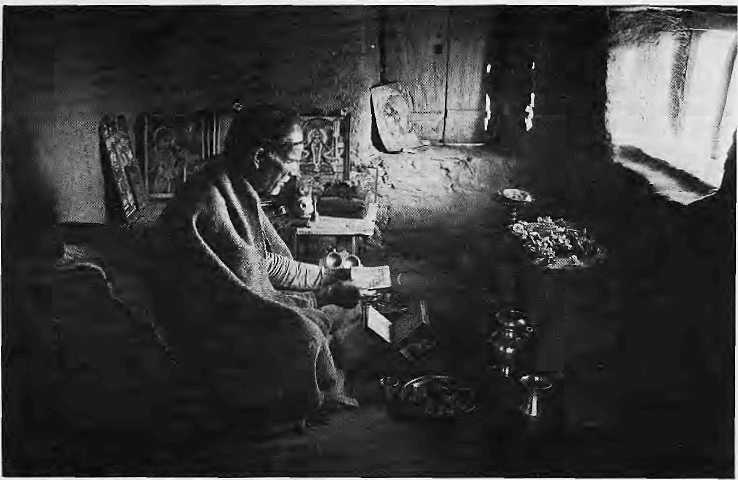

In the chill of the evening by the banks of the Bhagirathi River near Uttar Kashi, the stars are beginning to show as Mahant Shankar Puri raises his voice in high pitched praise of Shiva, lord of the snows. It is lime for arati, to mark the moment of cosmic transition from day to night.

Three hundred and fifty kilometres to the east, a pilgrim is on his way from the bazaar town of Doti for darshan with the eminent sage who lives in the high and isolated Khaptad plateau of west Nepal. He quickens his pace to get through the dense jungle.

A further 300 kilometres east of Khaptad Baba’s ashram, Shanta Maya Majarjan, 45, is returning home to the Kathmandu suburb of Thankot in a crowded evening bus. She has just been to Nagthan, where she propitiated the serpent deity that, she says, has been responsible for the severe pain in her chest and anrts.

Hira Lai Tamang, 27 from the village of Khopasi east of Kathmandu, is engaged in another kind of daily religious ritual. He is assisting his elder brother, a fully initiated jhankri, invoke the patron deity Mahadev to exorcise the demons that are causing a young girl to suffer from severe pneumonia.

Further east still, it is already dark in Tengpoche monastery in the heart of Khumbu, Just a tint of orange remains at the top of Mount Everest, known to the Sherpa monks here as Chomolongma, Mother Goddess of the World. The abbot of the monastery leads monks through sonorous prayers beneath electric lights, installed only this past year.

As night falls all across the ragged Himalayan landscape, when the mind turns, even if momentarily, to the eternal, millions of highlanders in the remote gumbas and bustling towns and sacred precincts are given to their particular variety of religious observance. The sadhu, the pilgrim, the housewife, the jhankri’s helper, all outwardly hold differing beliefs. Depending on locality, caste, ethnicity, upbringing and vocation, the practice ranges from the asceticism of the hermit through the philosophical erudition of the abbot to the unquestioning ritualism of Mrs. Maharjan. Perhaps the one thing these diverse practitioners of faith hold in common is that they all inhabit the Himalaya, doubtless the most revered region in the world, regarded by more people as holy than are the Alps, the Andes and the Rocky mountains of North America put together.

As the world approaches the Third Millennium, some would ask, why this unchanging belief on mysticism and religion? The holy lunar surface has been “defiled” by the footprints of astronauts and the sacred summits by mountaineers’ crampons, and yet religion continues to rule over the Himalaya. What relevance do religious percepts and practices gathered over thousands of years have for a people who have been asked to sign on to the latest religion, “development”, whose very premise is material progress? Can mystic beliefs be exploited for the purposes of social and economic advancement or are they to be discarded as hangovers from the past? Or should religion and ritual simply to be left alone, unchanneled, because they should not be “used” for any purpose?

These questions elicit as many differing responses as there ate sects of sadhus in the sub-continent, for religion is inseparable from daily life in the Himalaya, and every attempt at changing that life affects someone’s spiritual being as well.

Holy Slopes

As the closest links between the earth and the heavens, mountains have always attracted awe and reverence. The mysterious ridges and inaccessible summits became religious icons for societies all over the world. The Vikings of Scandinavia regarded Helgafell Mountain of Iceland with reverence just as Ik tribesmen of Uganda today revere Mount Murongole. Moses took delivery of the Ten Commandments atop Sinai. The Hopis of North America, the Maoris of New Zealand and the people of the Andes all regard mountains as the abode of ancestral spirits. In Japan, members of the Shugendu sect climb sacred peaks as purification exercises. For the Hellenes, Mount Olympus was a realm of divine bliss, inhabited by Zeus, Apollo, Aphrodite and other gnds and goddesses.

While the Greek gods have long since been declared dead, the deities in the Himalaya continue to receive the homage of the millions. Shiva, deity of destruction, the original yogi, sits meditating atop Mount Kailash. The gods of the Sherpas reside in Khumbila, a relatively minor peak which nevertheless towers over the Khumbu. The Lepchas of Sikkim trace their mythical origins to a primordial couple born from the glaciers of Kanchenjunga. The pre Buddhist Bon nature worshipers believed thai some of the peaks were places of spirits who were worldly beings. It is said that Padma Sambhava, or Guru Rimpoche, came to Tibet in 749 and converted the mountain deities, who then became the protectors of the Tibetan Buddhists.

Perhaps the Himalaya is the most revered simply because it is so big. It is the longest and the highest range, and its jagged precipices protrude dramatically from the Indo-Gangetic basin. These highlands would have not been as defined if it had been a slow-rising plateau. Mount Kailash, holiest mountain of the Hindus and the Buddhists, is the archetypical sacred mountain because it stands alone and rises so majestically. It is for the Himalaya what the Himalaya is for the rest of the world.

The Puranic progenitors of Hindu mythology even created a mythical mountain to be the epicenter of the cosmos — Mount Meru. With such reverence for the mountains, enthusiasm for the Himalaya can be catching. “Like the important nerve centres of the body which contain latent energy, the Himalaya mountains are vital geographical energy centres of the globe,” says Chos-Kyi-Jyima, head of the Ka Nying Shedrup Ling Monastery in Baudha, outside Kathmandu.

Yogis, Tantriks and Pundits

In their isolation, the Himalayan people developed and preserved the rich tradition of the past. Says John K. Locke, who has studied Newar Buddhism for over a decade, “Across the Himalaya, you have pockets of people who have retained cultures that have disappeared or become blurred elsewhere. For instance, the Newar community of Kathmandu is really the only surviving community practicing Indian Buddhism. The same is true of the tantrik Hindu cults that have been preserved here.”

The system of mental and physical control known as yoga, though not practiced by the populace at large, is an underlying element of Himalayan mysticism. Khaptad Baba is said to practice yoga prescribed by Patanjali. Tibetan Buddhism follows more closely the system of yoga laid down by Naropa, a twelfth century tantrik. The tradition of tantricism has deep roots in Himalayan Buddhism and Hinduism,

“Although tantra may conjure up apprehension in the minds of most people because of its association with eroticism and sexual imagery, it is basically a yoga,” says Locke. “It is a combination of various techniques to achieve the yogic goal, which is the union of Shiva Shakti (Consciousness Energy).”

The yogic and tantrik initiation is not reserved to the ascetics; among the few laymen who have reached deep into these traditions is Sridhar Rana, a teacher at a tourism training institute in Kathmandu. He began experimenting with the Hindu Tantra two decades ago and completed the prescribed series of mantra in eight years. For some of these, he spent nights on end at the cremation grounds. Rana then progressed to what is known as the “Witness Exercise” of the Vedantic school. He devoted the next six years to Zen Buddhism. For the past three years, he has been practicing dzog chen, an advanced form of Tibetan tantra.

While Rana might be the exemplary seeker, there are few like him among his urban peers in the Himalaya, and fewer still among the millions whose chief concern is to get through another day. In the mainstream Hindu tradition, especially among the emerging middle class, few engage in yoga or tantra themselves. Instead, the village pundit, the shaman and the lama step in, officiating for them to a multitude of deities and spirits. Rather than personally practice the deeper rituals, the majority of the population “practice religion by proxy”, says a Nepali sociologist.

Across much of the Himalayan midhills, the brahman holds sway. His function is to represent the Hindu pantheon, to man and the local temple, to direct all ceremonies and celebrations, and to collect dakshina. The pundit often plays and important role as an anchor of the community, dispensing advice on secular matter, dealing with governmental authority, and reading and writing letters. At the same lime he is also the guardian of superstitions and myths, and of the caste system that pervades the Hindu hill society.

Solace in Festivals

For the mountain peasant, his life bound to the elements and the environment, religion is a source of inner strength. With negligible cash income, the hard work in the fields, inadequate access to health facilities, and the constant threat of disease and death, the peasant has little to fall back upon in difficult times. The kind of religion practiced by the Himalayan peasant has its psychological and sociological roots in his lifestyle, say some social scientists. It is the spiritual equivalent to the social security that exists in the western countries.

G.S. Nepali, Professor of Sociology at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, says, “Religion as practiced by the Himalayan peasant is not other-worldly but this-worldly. Life is hard and he is not so much concerned with salvation, communion with God or life after death as he is with solving the day to day problems like hunger, misery and sickness. He therefore worships this god to get rid of certain diseases, that god for timely rain, another god to ensure a bountiful harvest, and so on. It is a completely utilitarian concept of God. Religion is a too! for adjusting to the environment.”

Adjusting to his own environment with nary a qualm is Asha Ratna Tuladhar, 32, from Gabahal in the town of Patan. Tuladhar is not quite sure whether he is Buddhist or Hindu but that does not keep him from actively participating in the festival of Rato Matsendranath. The festival is one of the most joyous collective activities in the Himalaya, in which the heavy, ungainly rath of the deity known also to the Newars as Bungadya and Karunamaya is hauied through the narrow lanes of Patan. At the end of the festival, Tuladhar and his family light up butter lamps and participate in bhoj, in which everyone eats and drinks to the celebration of life. “This is all in the worship of Karunamaya,” confides Tuladhar, “He gives us timely rain and good harvest.”

Nepali anthropologist Dipak Raj Pant is among those social scientists who feel that festivals are essential because they renew the life of a community. They believe that festivals, religious ceremonies and rituals do not have a mere mystical function, but also fulfill many other needs of people within a community. A traditional mela, for example, not only marks some religious event, but also provides opportunity for entertainment, exchange of information, commerce and even match making.

The Rationalist Approach

This view is not shared by journalist and political analyst Hiranya Lai Shrestha, who professes atheism. “Religious outlook is detrimental to modernization, too many resources are being spent on festivals. It has become impossible to disentangle religion from superstition,” says Shrestha. He is of the opinion that Nepal should be declared a secular state “to ensure the involvement of the various ethnic groups in national development.”

Those who agree with Shrestha say that religion has been one of the millstones around the neck of the nation, lulling the mind of the populace with promises of an afterlife and diffusing productivity by channeling its energies towards sacrifice, ritual, and self denial. They point to religion related rituals such as ostentatious weddings, which are often carried out by taking out loans, usually with precious land as collateral.

Others see religion as playing a subtler and useful role. “This is not the Shangri La that so many westerners would like to see,” says a Tribhuvan University professor who asked not to be named. “The peasants live harsh lives because of their poverty. But do they have a choice? Absolutely not. So at least grant them their religion, theiT festivals and their beliefs. Without religion, you would need a hundred thousand barefoot psychiatrists just to keep the nation standing.”

Heaven can wait.

Anthropologist Pant disagrees with the notion that a religious outlook is detrimental to modernization. He points out that in Europe, the Protestant Ethic helped pave the way to capitalism in the 16th and 17th Centuries. “In India, the process of religious awakening initiated during the 19th Century by Vivekananda, Aurobindo, Tilak and continued by Gandhi in the 20th Century brought about not only decolonization and independence, but also development.”

As for the call for secularism. Pant says it has “no meaning among the Hindus because their religion, if properly q understood, is < actually a & conglomerate of g? ideas, values, g norms, customs 3 and beliefs fabricated in a chaotic manner. In fact this chaotic cosmos is Hinduism’s most unique feature.” Regarding the claim that festivals lead to waste of precious resources, Pant responds, “A single political celebration like

Independence Day consumes more national resources than several festivals put together.”

Aum, the Common Mantra

While defending the role of religious practices in the life of the Himalayan people, anthropologist Pant is concerned of the tendency to impose a simple generic form of Hinduism on the people, “This homogenization is injurious to the traditions of national integration,” he says, adding that each community must have freedom to practice religion in its own way.

Such worries do not trouble the proponents of sanatan dharma, who are glad to see practices such as tantricistn and other “divisive” practices fall by the mountain trail. The more orthodox back to the Veda proponents are gaining ground in the mainstream middle class and they received a significant boost at the Fourth International Hindu Conference, held in Kathmandu last May. A positive effort was made during the Conference to broaden the scope of Hindu religious belief, and to incorporate all traditions that have grown around Hinduism, says Khem Raj Keshav Sharan, Professor of Sanskrit and President of Nepal’s Sanatan Dharma Seva Samiti. “The Conference was successful in bringing together Baudhas, Jainas and Sikhs alike. They all can be regarded as belonging to one family because they share Aum as a common mantra,” he says.

Lost in all the talk of the social scientists, anthropologists, rationalists, and orthodox standard bearers is yet another perspective. Beyond the world of the religious texts, rituals, sermons and analyses, is there something else, intangible, that makes the Himalayan people spiritually unique? What, after all, has attracted the plainsman and the foreigner to these mountains for centuries?

Abraham Joy, self-professed “seeker” from the United Stales, says he perceives that uniqueness. “I grew up with a vague sense that a higher force that created everything exists and requires respect. Yet I grew up in a godless world and found this sentiment constantly disproved. Nevertheless, it never went away and in Nepal I was happy to be around people who recognized and lived by it. Next to just about any Nepali villager, Americans seem like egomaniacs, with respect for nothing but power, money and rationality.”

Yet the irony of his search is not lost on Joy. He sees the modern man’s search for religion paralleled by the religious man’s search for modernity. “Somewhere between the two may lie the answer,” he says.

A Changing Landscape

Already, in the pilgrimage spots in Uttarakhand, the roads blasted in the wake of the 1962 Indo Chinese war have changed the meaning of a pilgrimage. A week’s ticket in a “semi deluxe video coach” takes the “pilgrim” through all the major sacred spots, leaving him little time to contemplate the grandeur of the hills, the meaning of penance, and life itself. Pilgrims to Kailash from far west Nepal walk a week to reach the border, whence they are whisked within hours to the banks of Manasarovar.

With creeping modernization, a growing cash economy, increased mobility, environmental dislocation and demographic changes the religious life of the Himalayan population is bound to change drastically within a lifetime. With that will also change the role and function of sadhus and mystics.

Hira Lai Tamang’s brother, the shaman, is being asked by Unicef to help popularize the use of oral rehydration salts by village mothers. When the Rato Matsendranath chariot gets bogged down in monsoon mud, it is a motorized crane that comes to the rescue rather than the willing hands of hundreds of devotees. Shanta Maya Maharjan might soon start taking asthma medication rather than trying to appease the serpent god. And now that the monks at Tengboche are reading by hydropower, will the electric light of modernity replace the inner light promised by the practice of religion?

Rajiv Tiwari assisted in reporting this article.