From Himal Southasian, Volume 14, Number 8 (AUG 2001)

When crises erupt, satellite television raises the pitch of Indian nationalism and gives it mass appeal. Bombay cinema hurries to catch up with ever-more fervid films, productions that have lately begun a no-holds-barred demonisation of Pakistan. Films from Lahore try to reciprocate, of course, but they hardly have the reach of Hindi films. The changing demography of the audience (see “Hindi films: The rise of the consumable hero”, p.8) must be playing a role in this increasingly belligerent treatment of geopolitical themes. In long-ago productions, the handsome hero would disappear over the horizon in his Canberra bomber, presumably to fight Pakistan, never to return (or perhaps to return when his beloved had already married his buddy). Back then, Pakistan was a remote enemy that, if ever brought into the script, served as but a prop to sustain the love story. With every new episode that tries to rip the Subcontinent apart—Pokhran/ Chagai, Kargil or IC-814— Bombay productions become more shrill. And, they get ever closer to Pakistan, across the line-of-control in Kashmir, amidst terrorist-infested redoubts.

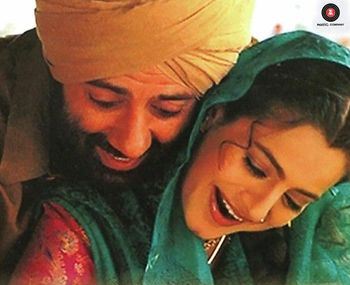

Gadar storms Pakistan’s Punjab itself. Starting as a love story that takes off during the Partition, with Sikh boy Tara Singh’s love for Muslim girl Sakina, the last third of the film all-of-a-sudden infiltrates Pakistani territory. Sunny Deol sneaks into Lahore to rescue his Amisha Patel, who has been kidnapped by her politician father, a former Amritsar businessman who has gone on to become the ambitious mayor of Lahore. While earlier in the film there are occasional attempts (a la Bombay) to balance the Hindu/Sikh magnanimity with Muslim friendship and support, once the script enters Pakistan (across an incongruous border lake), no need is felt for any gesture on behalf of the Pakistani Muslim.

The Pakistanis are depicted as an unregenerate dark-skinned, menacing force—from the consulate official to the daroga Suleiman (“I will cut him into so many pieces that he will be unrecognisable.”), to the mob that attacks the hero in Lahore. Even the peasant woman who gives the couple refuge as they flee towards India ends up a mercenary wanting to snatch Sakina’s mangalsutra. The climactic moment of the film occurs on the wide steps of what is obviously meant to represent the Grand Mosque of Lahore (reportedly shot at Lucknow’s Irshad Manzil, a Shia shrine, courtesy the BJP government in Uttar Pradesh). Surrounded by the evil adversaries, Sunny Deol goes into a polemical defence of the Indian state and then proceeds to pull a tubewell handpump out of its moorings to take on the enemy. The couple has a son, no more than eight-years-old, who is made to ask querulously, “What is wrong with the Pakistanis?” Sakina’s Pakistani father is not above having his daughter shot from a helicopter gunship. A whole platoon of Pakistani troopers are made mincemeat by Tara Singh as their getaway train speeds towards India. Suddenly, then the hero slows the train down to a crawl because a herd of cows is blocking the track. Some message there?

Could it be that Gadar visits Pakistan purely to be able to villainise Muslims across the border, given the backlash one could invite if this were done to Muslims of India? At other times, one wonders whether the film’s descent into Pakistan bashing had to do with the director Anil Sharma’s attempt to rescue the production from the unremittingly poor acting by Sunny Deol. It is not that the film does not have good moments. The cinematography is fine, and does justice to the wide vistas of village Punjab. The mass movement of people to the ‘other side’ during Partition is also captured well. There is a single indoor scene that is to be appreciated, where Sakina helps her sardar husband fold and tie his turban. Patel knows how to cry convincingly and runs with full stride, but Deol does not know how to dance.

Gadar was running housefull in theatres all over India, and on its way to becoming one of the top grossers of the decade, at the very moment that Pervez Musharraf was visiting Agra. There is no doubt that mass-based big-budget films such as this one distort political sensibilities and subconsciously sabotage the inbred peaceful sentiments of the people. This trend towards nationalist jingoism in the second-largest film industry in the world is worrisome because it impacts on the geopolitics of a very unstable and nuclearised South Asia.

Cedar fosters gadar. It is not only, the storyline of this movie that depicts frenzied mayhem, this soulless film itself encourages “frenzied mayhem”. It is clear that the producer and director named the movie for something that they like rather than something they see as negative. And, backing them are the financiers who realise that anti-Pakistan sentiment offers a treasury of commercial possibilities in present-day India.

They may be weak tools, but peer pressure and ostracism may be one way to get the producers and directors to back off. Unfortunately, since criticism of exploitative films such as Gadar is restricted to the rarified liberal-progressive echelon, this does not seem a near-term possibility in a film industry whose father figure is the reactionary Balasaheb Thackeray of the Shiv Sena. What this means is that films like these will be produced again and again till this particular genre is exhausted of its money-spinning possibilities.

While the impact of Gadar on the targetted Indian audience is the main cause for worry, it is nevertheless worth considering what kind of reaction it will generate in Pakistan, where it is being viewed via videocassettes and DVDs. Will they see it as a movie targetting themselves, or as just another adventure plot? Will they know to distance themselves from the Pakistan depicted in Gadar? Perhaps, for the film reviewer of the Newsline, the well-known magazine from Karachi, does not seem too perturbed by Gadar. S/he reviewer ignores the patriotic proclivity of Gadar, and is quite content to say: “Notwithstanding the two flaws in the film— its excessive length and weak musical score—cedar is certainly worth the watch for its brilliant dramatic sequences, commendable performances and touching moments.”