From Himal Southasian, Volume 12, Number 10 (OCT 1999)

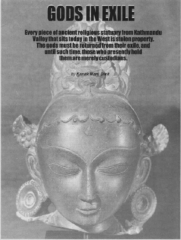

Every piece of ancient religious statuary from Kathmandu Valley that sits today in the West is stolen property. The gods must be returned from their exile, and until such time, those who presently hold them are merely custodians.

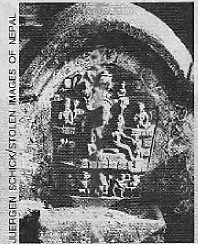

For 900 years, a sculpture of Uma-Maheshwar, showing Shiva- Parvati and attendant deities in Mount Kailas, had stood in a shrine at the Wotol locality of Dhulikhel town, east of Kathmandu. The grey limestone statue standing 20 inches was stolen in 1982 and today sits on a lonely pedestal at the Museum fur Indische Kunst in Berlin.

A 15th-century Laxmi-Narayan, half-Vishnu and half his consort Laxmi, was included in the 1990 sales catalogue of Sotheby’s. Dark granite shining under the spotlights, the image was valued between USD 30,000-40,000 and sold off for an undisclosed amount by the New York auction house. The people of Patko Tole of Patan town have not had the deity to worship since it was lifted in 1984 and today make do with a crude replica.

An 11th-century Uma-Maheshwar image, which for eight centuries adorned a hiti water-spout in Nasamana Tole, Bhaktapur town, is now a prize in the collection of the Musée National d’Arts Asiatiques—Guimet in Paris (“one of the largest art museums in the world”). Since 23 May 1984, when the sculpture was pried off its brick and mortar backing and taken away, the celestial couple has not received propitiation from the devout who come to collect water at the hiti.

Since the 1960s, thousands upon thousands of stone sculptures have disappeared in this manner from the temples, monasteries, fields and forests of Kathmandu Valley and nearby towns. The only way devotees can view these deities is by travelling across the oceans to see them displayed, spot-lit and isolated in private drawing-room pedestals and museum niches. Others remain locked up in storage vaults, and quite a few still turn up for sale, advertised in glossy magazines specialising in oriental art.

There are compelling reasons to become emotional about the theft of these Kathmandu Valley sculptures, wrested from the lap of worshippers and their sites of consecration centuries ago. In a museum, the statue stands polished and alone, its surface cleaned of worshippers’ grime of decades. An object of worship becomes an object of art. Says Chandra Prasad Tripathy, a specialist at the Department of Archaeology in Kathmandu, “When a statue is displayed in a museum, it is converted into an archaeological item which has lost its current cultural value.”

As the deities continued their journey overseas through the 1970s and 80s, Kathmandu Valley residents suffered the loss but did little else. Meanwhile, the Valley’s cultural vanguard showed a singular passivity. Partly, this fatalistic inaction was due to the logistics of tracing stolen items in the murky arena of antique art commerce. The larger explanation, however, has to do with the severely disorienting fallout of headlong modernisation, under whose weight the Valley’s age-old communal institutions have crumbled, and the value of ancient heritage become terribly downgraded. While the citizenry watched helplessly as the gods and goddesses went into foreign exile, the cultural elite looked the other way.

Four stone objects

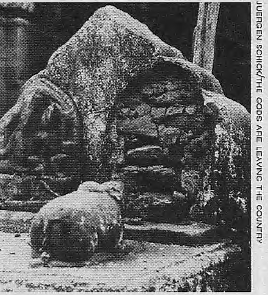

Till even a couple of months ago, it would have been difficult to conceive the idea of stolen divinity actually being returned to Nepal, but things have now changed dramatically. The beginning of August was witness to the first-ever voluntary return to Nepal from overseas of three stolen statues and a fragment (a severed Saraswati head). The cache was returned by an American art collector confronted with proof of their theft, and the very act of willing restitution—welcome in itself— now holds great promise for the thousands of statues still out there in the occidental cold.

Going beyond the matters of international legality and obligations, the August restitution was made on the force of moral and ethical considerations by a remorseful collector. This gives rise to the hope that thousands of other collectors, connoisseurs and dealers who hold their art treasures in private—unlike the more transparent custom of museums which may be persuaded more easily—may also follow suit if and when confronted with the reality of theft.

There is now, more than ever, a need for community activists, archaeologists and other public and private custodians of Nepal’s heritage to work together to actively seek the return of sculptural heritage that is today scattered throughout the West, from North America to Europe, Australia and Japan. Besides seeking the return of stolen cultural property, it is important to note that a loud and visible campaign would force down the value of artefacts, enough to destroy the future market for ancient Nepali statuary.

Fortunately, some solid groundwork for such a campaign has already been laid by Lain Singh Bangdel of Nepal and Juergen Schick of Germany, thus far criers in the wilderness who have worked for long years with commitment and courage against the idol-lifters (click here). Over the course of two decades, working independently of each other, Bangdel and Schick photographically documented hundreds of statuary in their original places, and also took subsequent pictures of the sites which had been ravaged. Taken together, these ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures provide incontrovertible proof of theft of more than 140 pieces.

The August restitution was itself the result—ten years later—of Bangdel’s 1989 work Stolen Images of Nepal. Among other things, the book contained before-and-after pictures of four particular shrines. It was Pratapaditya Pal, the US-based authority on Himalayan art, who noticed that a West Coast private collector held four of the pieces included in Stolen Images. Says Pal, “When I saw the sculptures in Bangdel’s book, I mentioned the problem to the art collector. The collector, who chooses to remain unknown, immediately agreed to return them unconditionally.”

Alerted by Pal, Bangdel wrote to the Department of Archaeology in Kathmandu, which acted quickly with the help of Nepal’s embassy in Washington DC to have the statues transferred to Kathmandu. Today, the four pieces are secure in the National Museum at Chhauni in Kathmandu, and are currently being displayed in a special exhibition (see page 13).

The Disappeared

The process of idol theft started soon after Nepal shed the Rana era and opened up to the world in the late 1950s. Western connoisseurs of Oriental art came upon a Valley which hosted a treasure trove of iconography in stone, bronze and wood – the artistic outpouring of the Valley’s prosperous and accomplished urban culture going back beyond the 5th century. As Bangdel puts it, “The early visitors found Kathmandu Valley like an open museum populated by tens of thousands of gods and goddesses.”

The theft of religious art began with small items that could be easily lifted—ritual paraphernalia, wooden articles, free-standing bronzes or those pried off torana friezes, and poubha and thangka hangings. In the early 1970s, the art smugglers shifted their gaze to the Valley’s ubiquitous granite sculptures, and the trade in stone statuary did roaring business over the next couple of decades. Like the Nataraja images of the Chola Dynasty of southern India (see following article), the Uma-Maheshwar images seemed to have been particular favourites of the collectors, for their reverential themes and fine sense of artistic proportion.

The 15th-century Chatrumukha Siva-linga at Pashupati.

Together with the museums and art collectors in the West, some Nepalis too had come to realise the value of images that lay strewn about their Valley. From the most powerful in the land to the neighbourhood thief, as well as functionaries of guthis (community trusts) and neighbourhood groups, many colluded in the theft of Valley statuary. Besides this, the acceleration of idol theft through the 1970s and 80s was made possible by the inaction of an entire spectrum of the Valley aristocracy and national elite, including the royal preceptors (gurujyu’s), the state-appointed administrators at the Guthi Sansthan responsible for religious property, and that very intelligentsia which sees itself as heir to the Valley’s glorious past.

Says a Western conservationist long involved in the restoration of Nepali cultural heritage, who prefers not to be named, “The worm is deep in the fruit on the Nepali side too. Look at the way the Guthi Sansthan operates as custodian, and the private guthis which are going to seed because of loss of income and breakup of clans and families.”

The period following the 1980 plebiscite in Nepal (which gave a mandate for continuing the autocratic Panchayat system under the king’s direct rule) was one marked by lawlessness and a lack of accountability among those in authority. This period saw a spurt in the disappearance of the Valley’s religious art. In fact, the bulk of the disappearance identified in the Bangdel and Schick books refers to the period between 1980 and 1986. Such was the extent of this plunder that there are some who believe that almost all that was worth stealing from the Valley’s open spaces was taken away during this period. “There is nothing left to steal.”

Contraband deities

It can be said with confidence that, with hardly any exception, every ancient stone statue from Nepal currently adorning pedestals in the West—has been the subject of loot. They had to be stolen because these communally-owned religious objects in public shrines could never have been gifted or sold. Juergen Schick is unequivocal, “The collectors in the West should know that almost all Nepali art that came into the market over the last 30-35 years was procured through theft.” Bangdel concurs: “Almost all the idols in the Western collections are definitely stolen.”

Pratapaditya Pal prefers to make a distinction between the takng of art objects from a site and their departure from the country. “Some of the objects belonged to certain communities, which may have had the legal right to sell them,” he says. “However, one can claim that most objects left the country illegally.”

While it is indeed possible that that some of the smaller free-standing bronzes and religious wall-hangings may have been willingly given or sold by their Nepali trustees or custodians, even these would have left Nepal against the country’s laws governing ancient art (which prohibits the departure of any item more than a hundred years old). However, even this fig leaf of minimal respectability is not available for those who currently possess stone sculptures, all of which would invariably have had to be pried away from temples niches, altars and shrines on their way to foreign exile.

Says Riddi Pradhan, Director General of the Department of Archaeology in Kathmandu, “There is no doubt about it, nearly every one of our statues left the country as contraband, against our laws. They are stolen goods, and hence remain the property of Nepal, owned by the country and the communities where they were originally situated.”

“Thousands of pieces from the Valley today fill up 25 museums of the world. The Valley is bled white of its heritage, while the museums’ collections gain incredible riches,” says Schick. Adds Bangdel, “The fact is that, while they may not know it, collectors, art dealers and museums all over the West are in possession of objects which have been stolen from their sites or illegally smuggled out. Once it is proved that they are stolen art objects, no one has the right to possess them.”

Push and pull

As with any cultural property, the attraction of Kathmandu Valley sculpture has to do with the collector’s need for rare artefacts of ancient, exotic and unusual pedigree. This artistic inclination becomes a travesty when the collector directly or indirectly is involved in the chain of events which surround the theft, transport, sale and accession of an Uma-Maheshwar or Laxmi-Narayan, representatives of a living culture far enough away to feel detached and ‘cultured’.

According to one Kathmandu scholar who minces no words, “Idol theft is a demand-driven trade led by rapacious cultural cannibals. The culprits are not the petty thieves who in any case earn a pittance compared to what the art will fetch under the gavel in New York City.” The only way to stop this trade in contraband deities, he says, is by hitting at the demand so that impoverished Nepalis at the bottom of the smuggling chain do not feel the need to wrest statues from their moorings to ship them off.

The overseas demand for Valley loot constitutes the ‘pull factor’ as far as the trade is concerned. The ‘push factor’ is located in the weakened traditional institutions of Kathmandu Valley, an absence of social leadership, as well as the greed of Nepali thieves right up and down the social ladder. “There is hardly any sense of responsibility here for the incredible treasures handed down by history,” says the Western conservationist referred to above resignedly. “There is a near-total absence of outrage, and no thought given to reclaiming the statues.” He has a point there, but nothing to change the fact that every ancient stone statue currently held by private and institutional collectors in the West is stolen property. And if something is stolen, simply and irrefutably, it must be returned.

There are, of course, international treaties which lay out the principles for restitution of stolen art (even though most of the Western countries which hold stolen art are not signatories). The most important instruments are the 1970 Unesco Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen and Illegally Exported Cultural Objects. (UNIDROIT is the Rome-based International Institute for the Unification of Private Law.) There are also elaborate modalities for the reporting and return of stolen objects, using Interpol, the World Customs Organisation, the Art Loss Register, the International Council of Museums, and other governmental and non-governmental agencies.

However, it is the Paris-based United Nations agency Unesco that is the point organisation when it comes to requital of cultural property, and the agency is clear when it comes to smuggled Nepali statuary. As Lyndel V. Prott, who is with Unesco’s Division of Cultural Heritage, wrote in a letter to Himal, “Unesco shares your concerns regarding thefts of sacred and ancient works of art in Nepal and is naturally willing to assist in recovering this cultural heritage through wide dissemination of the information, education of the local communities, and sensitisation of dealers, collectors and museums.”

The 1995 UNIDROIT convention was developed to deal with some of the legal issues insufficiently covered by the 1970 Unesco convention and provides an international framework to enable claims of illicitly trafficked cultural property to be pursued within national legal systems. The Convention states, as Prott emphasises, “that the possessor of a stolen cultural object must return it regardless of personal involvement or knowledge of the original theft”. Additionally, the Convention denies any compensation for the return unless “the possessor neither knew nor ought reasonably to have known the object was stolen”.

Elgin Marbles to Uma-Maheshwar

These two international instruments and various other modalities will come into use in the larger campaign to have stolen Nepali art returned to the country, and it will help when the countries which host most of the stolen artefacts (e.g., Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) join them as full-fledged state parties. However, the moral and ethical imperative itself is strong and impelling enough to begin the campaign for the restitution of stolen Kathmandu Valley art. Indeed, the voluntary despatch of religious objects by the American collector in August is the first and most eloquent example of the feasibility of this exercise.

Demanding the return of images and icons taken away by Western museums is hardly anything new. One of the most celebrated examples is that of the so-called Elgin Marbles, statues from the Parthenon which were transferred to the British Museum for “safekeeping” more than a century ago. This campaign for restitution is being pursued even today by both the Greek government and independent activists.

However, inasmuch as there is compelling basis to demand the return of the Greek marbles—or Inca jewellery, Pharaonic statues or (much closer to home) Gandharan Buddhistic art for that matter, there is a significant difference with regard to Kathmandu Valley iconography. For, the smuggled Valley images were part of a living culture rather than merely part of Nepal’s archaeological heritage. As Lain Singh Bangdel observes, these are not mere objets d’art, but pieces made “alive” by veneration. Till the day they were stolen, these idols were being reverenced and their loss is still deeply felt. (The empty pedestals of statues lifted decades ago still receive tika in Kathmandu Valley to this day.)

There can be no questioning the suggestion that religious art which received tika and flower offerings till the day (night, mostly) of plunder should be returned with an even deeper sense of urgency than archaeological loot. As far as Kathmandu Valley iconography is concerned, the process of restitution can be said to have begun with the return of the four pieces in August, but there are thousands of statues out there which await recovery. A concerted campaign to return statuary would have to start with the understanding that because every ancient religious stone statue originating in Kathmandu Valley and surrounding region is known to have been stolen, every person and institution possessing such statuary must consider himself/itself to be in possession of stolen property. Those who currently hold such cultural property must regard themselves as a custodian holding the object(s) in trust.

The place to start with the campaign for restitution seems to be bringing back the stolen works documented by Lain Singh Bangdel and Juergen Schick. Among them, the whereabouts of the statuary taken from Nasamana Tole in Bhaktapur, Wotol in Dhulikhel, and Gahiti in Patan is known – they are in the the Musée Guimet in Paris, Berlin Museum fur Indische Kunst and the Denver Art Museum, respectively. Also, since it is known that the Laxmi-Narayan from Patan’s Patko Tole was sold in 1990 by Sotheby’s of New York, the auction house would be duty-bound to help trace it. And if both the return of Nepali statues in August and the experience of India (see story) is any indication, it should not be all too difficult to begin the process of their return.

Before and after

The next step for the activists would be to attend to the remaining more than hundred figures, the fact of whose theft has been similarly photographically documented by Bangdel and Schick. Identification, location and return of these gods and goddesses will require sustained investigation and activism by art and heritage lovers in Nepal and elsewhere. Before-and-after images of the burglarised shrines should receive the widest possible distribution, through individual mailings, magazines and newsletters, over the Internet, and so on.

Lastly, and on a global scale, art and heritage lovers would have to get involved in the task of sensitising everyone engaged—in whatever manner—with Oriental art that each and every piece of stone statuary with origins in Kathmandu Valley is presumed stolen unless proven otherwise. Further, those who hold stolen Valley art must be reminded that at most they are, as suggested earlier, custodians or trustees of what they hold and not owners. A high-volume, well-documented campaign for restitution of valley statuary would serve the dual purpose of returning stolen artefacts as well as killing the demand which would lead to further thefts.

Given the state of insecurity even today regarding openly-kept statuary in Kathmandu Valley, it is not necessary (and may not even be desirable) that every recovered statue be returned at this time to the shrine or site of origin. Indeed, the recent spate of thefts in Patan (including the head of a bronze Mani Ganesh stolen recently from the heart of town) points to the need for extreme caution in this regard. Only local communities which are united and confident in providing security may and receive permission from the Department of Archaeology for complete restitution.

In the case of the majority of recovered objects, given the overall state of Nepali politics, economics and societal inaction which leads to an insecure environment, a ‘partial restitution’ is probably advisable, where the gods and goddesses are returned to Nepal, to await a secure day in which to enter their original shrines and abodes. The repository for returned statuary till such time would be the National Museum at Chhauni, Kathmandu, where the Nepali army stands guard. The National Museum already houses scores of locally lost-and-found

images, and is also where the four pieces which came back in August are in safekeeping.

There will come a time when all the returned statues will have been restored with confidence to their original homes. This time will arrive when the market for stolen art from Nepal will have been destroyed, when their spiritual value is understood by everyone and their dollar value will have plummetted. This will not happen, however, before Nepal’s social elites themselves begin to understand and feel for their gods in exile.

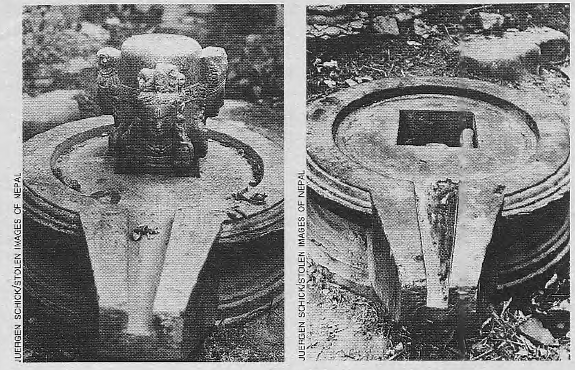

WOTOL AND NASAMANA

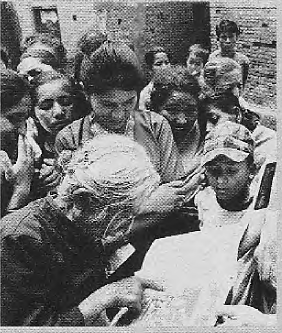

It is natural for neighbourhood residents to want their stolen statues back. In Dhulikhel’s Wotol, elderly ladies crowd around a copy of Lain Singh Bangdel’s Stolen Images of Nepal, which shows clearly the image of their Uma-Maheshwar as it was originally in the neighbourhood shrine. They find it hard to believe that the statue has been located years after it disappeared, at the Berlin Museum.

“Do everything you can to bring it back, please!” says 75-year-old Nanimaya (see picture) as she studies Bangdel’s book. She then agitatedly points to the spot where a rounded rock receives the flowers and tikas meant for the Uma-Maheshwar. The nandi bull is still there in attendance of Shiva and Parvati, even though the qodly couple are some thousands of miles away.

Among the elderly menfolk gathered in Nasamana Tole in Bhaktapur’s Ward No 13 to study Stolen Images is Ram Bhagat Twayana. Unlike some of the younger residents present, he easily recognises the image of the Uma-Maheswar which disappeared from above the hiti’s water spout on the night of 23 May 1 984. When the group is told that the icon is presently at the Musee Guimet in Paris, every member is emphatic that it has to be returned. Says Krishna Gopal Hada, the Ward’s representative in the Bhaktapur town council: “We must get this statue back. We will go to the airport when it comes and welcome it back with baja gaja, with pomp and festivity. The whole town of Bhaktapur will celeb rate the event!”

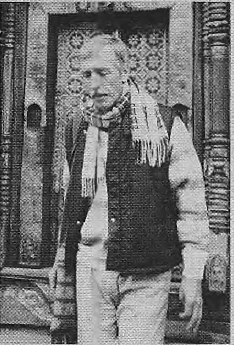

BANGDEL AND SCHICK

For three decades, while the Kathmandu Valley public remained largely blase and uncaring about the terrible loss being inflicted upon its heritage by idol thieves, two individuals with origins elsewhere were unrelenting in their campaign to document the loot.

Artist and art historian Lain Singh Bangdel and Juergen Schick, an art connoisseur from Essen, Germany, emerged as guardians of statuary in a Valley where modernisation and breakdown of community spirit had left thousands of icons in the fields and neighbourhoods virtually orphaned. Bangdel’s and Schick’s writings and photographic records of important statuary, the shrines before and after theft, as well as their publication of endangered icons, have been the most potent weapons thus far against the spectrum of art bandits which stretches from the petty thieves in Kathmandu Valley to faraway galleries.

Lain Singh Bangdel, born in Darjeeling in 1 924, arrived in Nepal in the early 1 950s after completing his study of art in Paris and London. He was immediately impressed by the Valley’s ancient treasures, and set about studying them, publishing several scholarly volumes. As art theft peaked in the mid-1980s, he began preparing his book Stolen Images of Nepal. It was published by the Royal Nepal Academy (which he had earlier headed as Vice Chancellor) in 1989.

Juergen Schick arrived in Nepal overland as a budget traveller in 1 973, and he came back to settle in 1 980 with his Nepali wife. His plan was to document the art heritage of this vast “open museum”; but as he started travelling to far corners photographing iconography he realised that they were being stolen even as he recorded them. Schick recalls, “With ever greater frequency I would come across gaping emptiness where just a few days previously I would have photographed a beautiful god.”

Schick made his personal shift from art connoisseur to activist in the spring of 1 984, when idol-theft in Kathmandu Valley was at its high-water mark. The robbery of two images hit him particularly hard. One, an 800-year-old black granite statue of Laxmi-Narayan in Bhaktapur which disappeared one night, and the other an exquisitely carved 1 6th-century image of ‘veenadharini’ Saraswati, from the village of Pharping on the Valley’s southern rim. Schick had photographed the sculpture in May 1 984, but when he returned in December, he found it decapitated. Unable to lift the whole statue, the thieves had severed the head with a sledge-hammer blow and taken off with it. “It was then and there that I decided to pursue this phenomenon of cultural crime,” recalls Schick. (This Saraswati of Pharping is pictured on the cover of this issue, and the head is one of the pieces returned in August. See opposite page.)

Working independently of each other, for both Bangdel and Schick, the exercise in photographic documentation rapidly evolved into a race against time. Their task was to photograph as many images as possible so that at the very least there would be proof of origin of stolen statuary. Says Bangdel, “I felt it was important to provide strong and authentic photographic evidence of sculptures which were stolen from the Valley and surrounding areas.”

It was important not only to document, but also to publish the ‘before’ and ‘after’ photographs, so that a) the fact of theft was proven, and b) the market value of statues still in place would plummet amongst museums, collectors, antique shops and auction houses. The same year that Bangdel came out with his celebrated Stolen Images, Schick produced The Gods Are Leaving the Country (published in German and only recently out in English, by White Orchid Books, Bangkok).

As Schick says, “Both Mr. Bangdel and I produced our books to bring down the market value of the images. Also, the pictures would provide undeniable proof that the pieces were stolen. If we do a good job of publicising the art that still exists in shrines, then they will stop turning up for sale in the West.”

At a time when Nepali society as a whole, including the Valley communities themselves, seemed unwilling or unable to do anything about the flight of the ancient objects of worship, a Nepali artist and a German activist thus courageously took up the task of documentation. Those were lonely and dangerous years for both, as the autocratic Panchayat regime was at its arrogant worst — to the extent that robbers connected to the most powerful in the land felt confident enough to use a crane to try to pry the full-size Bhupatindra Malla statue from atop its pillar at the Bhaktapur Durbar Square.

Bangdel, despite his stature as one of the country’s foremost artists and head of the Royal Nepal Academy, was threatened with his life if he kept up his photographic crusade, and foreigner Schick was harassed, as is the custom, over his visa. He spent one whole desultory year in Germany with his family when he could not even enter Nepal. Recalls Schick, “When I found Mr Bangdel at the Academy, at last I had the one Nepali who showed a sensitivity to this subject. No one else.”

But both kept at it, and have ended up making a small difference—the best proof of which is the return in August of four pieces pictured in Stolen Images. If a few more statues remain in Nepal, credit must go to their books which brought down the market value for them in the international arts bazaar. And if there is still a possibility to have the scores of stolen statues returned to the Valley, it is because they have documented the theft to such an extent that it is impossible for any fair-minded collector not to return them. (The information in the main story on the whereabouts of the idols in the various museums was also provided by them.)

“I only wish I had come to Kathmandu a decade earlier so that I could have documented much more,” says Schick. “So much art had already disappeared over the 1970s.”

QUICK AND EASY

Numerous statues all over Kathmandu Valley can be found today protected behind iron bars, locked in steel casings, or fixed to unsightly cement. But better this than in a museum in the West.

Fewer stone statues from all over Kathmandu Valley would have been stolen since the 1960s, had some innovations been tried in times of security. Today, the security of deities is still left largely in the hands of inadequate, often elderly, attendants. To the last one, where there are even doors to temples, these are flimsy wooden contraptions with latches that can come off with a simple hammer blow or push. Temple doors could easily be backed by steel plates without taking away from the aesthetics, electronic burglar alarms and movement detectors could be used at affordable costs, and shrines could be floodlit at night…

Stone statues, mostly in stele form, seem to have departed with remarkable ease. This is because when they were carved and consecrated in their spots, no one considered that centuries later they would be the target of collector-bandits. As a result, most were put in place with a simple backing of brick and mortar (see above). All that is required to carry them away, therefore, is to shake them from their moorings.

A majority of free-standing stone statues could be protected by merely making it a little more difficult for a thief to carry them away, something which would make him work on the theft, take some time and make some noise. For example, the Uma-Maheshwars steles can be secured by giving them full-size backing, in which a rim of stone, cement or metal would overlap the edge of the statue by as little as a centimeter. This would require the thieves to, at the very least, use pick and hammer to pry the statuary lose. This would be time-consuming and create a bustle enough in the majority of cases to alert the neighbourhood and send the thief fleeing.

In other words, anything that prevents quick and easy theft will help in securing the statuary of Kathmandu Valley, those that are still left.