From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 9 (SEP 2007)

The fact is, India and Pakistan are developing nuclear weapons and missile-delivery systems even as we speak. The lull in diplomatic acrimony between the two countries is cold comfort: there are simply too many variables in play for a situation not to arise, eventually, wherein one side will make a pre-emptive nuclear strike on the other. The other will then respond, and true Armageddon will be upon us – a Kalratri that will change the world as we know it.

But for the moment, anesthetised by our own inability to fight the relentless push towards nuclear weaponisation – marked most gruesomely by our failure to get the public at large rallied against the development of these weapons – we wipe all thoughts of the bomb from our minds. We need ways to pinch ourselves in the brain. One such way is by physically meeting the Hibakusha, the survivors of the American atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

1945.The sixth of August, just after eight in the morning. It was at this moment that the first of two nuclear bombings in history occurred, in the sky above Hiroshima. The Japanese would surrender before long, and the war would soon end, but the US military high command nonetheless wanted to test out its atomic toy, and justify the high cost of the Manhattan Project. And so, Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima.

Sitting at the solemn and oddly regimented memorial ceremony at the Hiroshima Peace Park, the eye goes past the memorial cenotaph and peace flame to a point in the cloudy sky about 600 metres above the city – where, on that morning back in August 1945, Little Boy exploded.

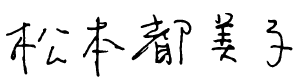

Tomiko Matsumoto was at the morning assembly out in her schoolyard, 1.3 km from ground zero. She was turned away from the lightning blast in the sky and the terrible wind that followed. Her entire back was charred, but she survived, to become one of the Hibakusha – living testimony to the horrors of nuclear weaponisation.

Those of Tomiko’s friends who were facing the blast had their eyes melt and innards explode. They joined the ranks of the 150,000 citizens who died within the year. “All the houses were down. There was no road to walk on,” Tomiko recalls. “There were corpses and flies everywhere, and the smell of blood, pus and excreta.” Tomiko’s mother and three-year-old brother died in the blast. Nothing is known of her other, five-year-old brother. Her father, who was two kilometres away from ground zero, received a heavy dose of radiation from the black rain that fell on him. Within a month he was bedridden; in 1948, he took his own life.

The testimony of one Hibakusha, multiplied a million and more times over, would be the minimum of Southasia’s suffering following a nuclear conflagration here. The mindset of the Indian and Pakistani military, shielded by geostrategic and ultra-nationalist considerations, would be no different than the cold calculations made by the Target Committee at Los Alamos, meeting on 10-11 May 1945. Just as alternative strategies were made to target Nagasaki, Kokura, Yokohama and Hiroshima, the Subcontinent’s nuclear-strike planners would have considered cities near and far, large and small – Jalandhar, Hyderabad (Sindh), Nawabshah, Karachi, New Delhi, Bombay, Bhopal, Multan. Amritsar and Lahore would not likely be targets, due to the fallout that would radiate from cities so close to each other and to the border.

The possible effects of nuclear war on New Delhi or Bombay have long been laid down by scientists. In a paper published in June 1998, the physicist M V Ramana suggested that even the detonation of a “very small” nuclear weapon over the Fort area in Bombay would flatten the downtown area from Victoria Terminus to Colaba. Exposure would also instantly kill anyone who happened to be within a 150-square-mile radius of Greater Bombay – conservatively, at least 300,000 people. Wrote Ramana, back in 1998: “The only guarantee that such a tragedy would never occur is complete elimination of nuclear weapons, both from the region and from the world, and the means to manufacture them.”

But in Pakistan and India, those who speak against the nuclear-weapons race are now considered romantics. But the fact is that most anti-nuke-wallahs of the pre-1998 Pokhran and Chagai era turned out to have wobbly knees. The marriage of ultra-conservatism with nuclear nationalism made it difficult to fight the tide, and an anti-nuclear mass movement failed to spark because there were so few to give it leadership.

Two days after the Hiroshima bombing, Albert Camus wrote an editorial in the French newspaper Combat: “Mechanised civilisation has just reached the ultimate stage of barbarism. In a near future, we will have to choose between mass suicide and intelligent use of scientific conquests. This can no longer be simply a prayer; it must become an order which goes upward from the peoples to the governments, an order to make a definitive choice between hell and reason.”

When the people of Southasia, in whichever region or country, are able to be heard by the governments in New Delhi and Islamabad to pull back from hell in the name of reason, then we will have finally achieved civilisation.