From HIMAL, Volume 7, Issue 4 (JUL/AUG 1994)

Bhutan today teeters on the edge of geopolitical ruin. It could tip over, or it could recover in time. It is, basically, up to King Jigme Singye Wangchuk.

In 1990, the rulers of Bhutan, a coterie of inter-related Ngalong elites from the western districts, initiated a successful depopulation exercise which has by now rid the country of a little over one lakh individuals. These are Nepali-speaking people, a majority of them Bhutanese citizens as even King Jigme Singye Wangchuk would have earlier acknowledged.

The eviction exercise was carried out in order to reduce the proportion of the Nepali-speakers, Lhotshampa, which a 1988 census showed to be higher than expected. The regime decided to act swiftly, using a combination of premeditated violence and mass intimidation, creating a fear psychosis which was channelled into orchestrated “voluntary emigration”. Although a trickle of refugees continues to emerge from Bhutanese roadheads in the Duars, the bulk was out by late 1992, and lives today in eight refugee camps in Nepal’s southeast.

Thimphu initiated an effective public relations effort to dupe the world while engaged in a cultural wipeout. A tiny, seemingly vulnerable country ruled by a sophisticated and self-righteous nobility carried out a brazen operation which it continues to defend without censure or sanction.

Thimphu has used every opening to its advantage, from political confusion in Nepal, to the availability of a starry-eyed Indian and international media that loves efficient monarchies. It has also cleverly played on Western concerns for an exotic and indigenous Tibetan culture supposedly being swamped by a Nepali tide.

If individual lives are sacrosanct and the right to life applies equally to Lhotshampa and speakers of Dzongkha, the language of the country’s north, only a observer equipped with cultural blinders would regard the regimes action justified. The count is 86,000 Lhotshampa, most of them peasants, housed in the UNHCR-administered refugee camps, and another 30,000 or so scattered across Nepal, West Bengal and Assam. The visual proof is in the empty fields of the Sarbhang, Chirang, Saatchi, Dagana and Samdrup Jonkhar districts of Bhutan’s south, where probably for the first time in the millennia of human habitation of the Himalaya swaths of farmland are reverting back to original jungle.

Welcome to the World

The charmed hiatus in which Thimphu finds itself is bound to end before long, for there are obvious limits to credibility in selling a flawed programme. Thimphu strategists who sat down in 1989 to chart the present course did not contemplate that there would be a refugee problem, nor that it would fester into the mid 1990s. The eviction operation was supposed to be brutal and swift. The Lhotshampa would disappear into the night, after which Bhutan would revert back to its self-image of innocent hermit kingdom.

But evictees became refugees and lingered in the camps as a blot on the national record. Despite continuous image management, the aura of Shangri La is now sullied. Says Ravi Nair, the Delhi-based human rights activist, who has followed the issue since the first refugees emerged, “The carefully nurtured image has shattered among those who follow the politics of South Asia. People have understood what the Bhutanese game is.”

Meanwhile, the refugee leadership, while riven with conflict, survives to fight another day. A northerner-only political party in exile proposes to plumb the depths of disaffection among the Sarchop and Ngalong communities. The hapless political and bureaucratic machinery of Nepal has thus far been more help than hindrance to Thimphu, but a Nepali government might yet emerge to put up a fight. Similarly, the United States’ clear public stance against Thimphu, while still only rhetorical, could translate into some kind of action.

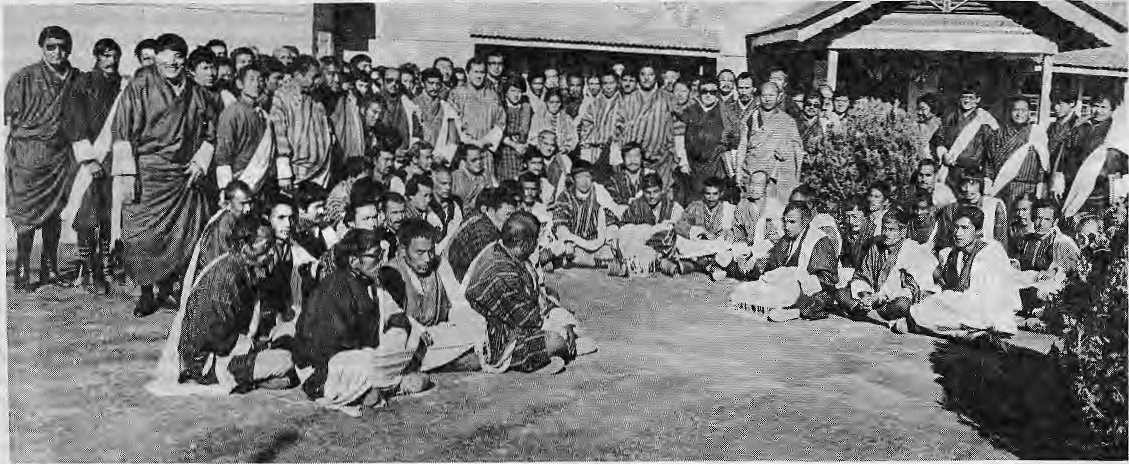

Deuba and Bastola take Druk Air to Paro.

India’s steadfast support for the Bhutanese regime is cold comfort due to the potential it has to take a strategic about-turn the moment King Jigme is seen to falter. As of February, J.N. Dixit, a friend of the regime during whose term India’s present Bhutan policy was defined, is no longer Foreign Secretary in South Block.

Exactly two years ago, when Himal first covered the Bhutanese crisis (“The Dragon Bites Its Tail”, Jul/Aug 1992), the pertinent question seemed only that of the refugees and their return. While negotiations on repatriation remain the supposed task of the Bhutan-Nepal Joint Ministerial Committee, Bhutan will increasingly be judged, like any other nation state, also on the basis of its record on human rights and representative governance.

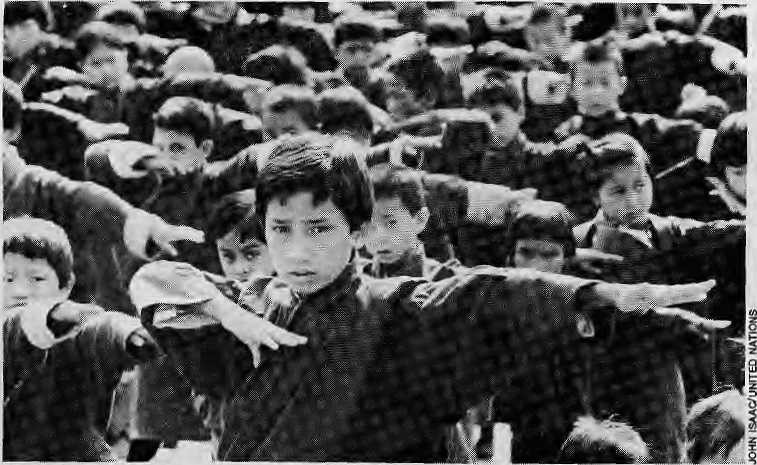

By initiating the mass-scale eviction of Lhotshampa, King Jigme inadvertently accelerated the entry of his closed kingdom into the 20th century world of political parties, open and acrimonious discourse, and activism. The programme of eviction and its fallout over the last four years has politicised not only the Lhotshampa (both refugees and those who remain inside), but also northerners of the east and west. Inevitably, even as they are being asked to condemn the southerners, the Ngalong and Sarchop populations are being exposed to novel ideas and processes. Right or wrong, group politics is about to swing away from the dictates of feudal subservience.

Even if Bhutan were to countenance a return of only a fraction of the refugees, this will not be the quiescent group that fled the country. And what of the refugee captains of today? Certainly not a docile return to civil service and the teaching occupations that they emerged from.

Whichever way the refugee problem itself is resolved, the stage is set for Bhutan’s late entry into the unstable world of South Asian democracies. King Jigme has told one over-awed interviewer after another over the last decade that he knows monarchy is not the best system of government and that when the time comes it will be gone. It would be unfortunate if the king had his wish fulfilled sooner than he expected.

Joint Ministerial Charade

Since July 1993, the fig leaf of movement on the diplomatic front has been provided by the Joint Ministerial Committee, set up under their respective home ministers by Bhutan and Nepal to resolve the refugee question. The Committee’s four meetings have thus far been marked by Bhutanese stonewalling and Nepali indulgence. The positions of the two sides are irreconcilably mismatched, but both have preferred to project an illusion of progress.

The Committee’s task is to distinguish Bhutanese citizens from non-Bhutanese and repatriate the former. At first glance, a relatively simple task—to identify the antecedents of no more than 16,000 families. However, the exercise is made difficult because Bhutan insists on retroactive application of its laws on citizenship in a manner that would leave tens of thousands stateless. Furthermore, Bhutanese law also takes away the citizenship from those who emigrate—the reason why Thimphu orchestrated the “voluntary departures” of many Lhotshampa (recorded with preprinted forms, forced signatures, video tapes and photographs).

Jay Khempo,

Thimphu’s

spiritual head.

In the Committee, the Bhutanese team has walked circles around the Nepali side, forcing the latter to accept self-denying compromises at every turn. It overrode Nepal’s proposal that an independent panel verify refugee citizenship, after which it was decided to hand the delicate task to a bilateral team. In a fit of absent-mindedness that left the refugee leaders aghast, the Nepalis also agreed to Thimphu’s proposal that the refugees be divided into four categories: “bonafide Bhutanese if they have been forcefully evicted,” “Bhutanese who emigrated,” “non-Bhutanese people,” and “Bhutanese who have committed criminal acts”. When Nepal said it was time for the bilateral verification team to travel to the camps, Home Minister Dago Tshering backtracked and was adamant that first there be an “exchange of positions” on the four categories.

Acquiescence on categorisation was only to keep the talks from breaking down, according to the Nepali side. “It is true that we have not taken the offensive against a small neighbour,” Home Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba told a public meeting in May, “But we have not given up anything by agreeing to categories. As far as we are concerned, all categories other than the one which refers to ‘non-Bhutanese people’ are Bhutanese citizens and will have to be repatriated.”

The task before Deuba and his team is an impossible one: to insist that Bhutan accept back individuals that it insists are non-citizens according to its domestic laws. There is no way that this matter can be resolved on principle without involvement of independent experts, who will have to decide, one, on the international norms and practice as they apply to citizenship and the Lhotshampa, and, two, on that basis conduct the task of identifying camp residents who are Bhutanese citizens.

“There is no substance left to the ministerial talks. The Bhutanese have made a conscious and deliberate decision to stall, while the Nepali side has decided not to be proactive,” says a Western diplomat.

On its own record, the Joint Ministerial Committee has become irrelevant; with the political turmoil in Nepal and the.mid-term elections announced for the Fall, it will become even more peripheral to the national agenda. Nepal can salvage its position only by forcing a deadlock when the teams meet next, possibly in September, and withdraw from the charade.

Bhutan vs. Nepal

“The Nepali side has blundered at every step on the refugee issue. It is outgunned and outmaneuvered by a country that has the best foreign affairs secretariat in South Asia,” says Ravi Nair. Sanjoy Hazarika, of The New York Times, agrees: “Dawa Tsering is one of the smartest diplomats I have met. He has played the southern problem with consummate skill.”

If that is how smart Dawa Tsering is, Nepal has not even had a foreign minister to speak of, the portfolio having been held by a disinterested Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala since he took office in mid-1991. A senior Nepali official admits that with so much on its plate, the Government has been unable to pay attention to the refugee question, “whereas Bhutan has concentrated fully on the issue.”

Nado Rinchhen, Bhutan’s Ambassador to India and Nepal and member of the bilateral committee, believes that Bhutanese diplomatic acumen is exaggerated. “Nepal can keep diplomatic contacts all over the world, whereas we have only five missions and no senior career diplomats. The number of international delegations that visit Kathmandu in a month, we have coming to Thimphu in a year.”

But then Bhutan knows where to pinch and where to jab. It has just despatched the urbane former Home Secretary Jigme Thinley as ambassador to Geneva, where human rights and refugee matters are discussed. Nepal’s understaffed Geneva office is not at ambassador level and is unable to counter the Bhutanese offensive directed at the highest echelons of UNHCR, ICRC and Amnesty International. Bhutan’s election recently to the UN Human Rights Commission has greatly enhanced Ambassador Thinley’s ability to make friends and influence people at high places.

Bhutan has reaped advantage from numerous Nepali weaknesses: the Koirala Government’s continuous preoccupation with challenges from the Left Opposition and from within the ruling Nepali Congress party; a Foreign Ministry that is terminally afraid of taking initiatives and does not even maintain a complete dossier on Bhutan; and even the fact that the two political appointees in Nepal’s negotiating team—Minister Deuba and Chakra Bastola, Ambassador to Delhi and Thimphu—do not see eye to eye.

Thimphu is also fortunate that Nepal does not have a stated policy for when descendants of historical migrants are forced to return en masse to its borders. Smaller groups have previously been dealt with on an ad hoc basis, but the Lhotsharnpa’ s arrival should spur the formulation of a paper on the matter. A sudden “cleansing” exercise in the Indian Northeast, for example, could lead to a repeat of the Lhotshampa influx.

Chakra Bastola (who is expected to resign his ambassadorship to fight the elections) is unambiguous on the Nepali stand on the Lhotshampa: “Nepal is not a party to the whole affair. We are not part of the mudda. This is an issue between the Thimphu and the refugees, who happened to have entered our territory but who we refuse to accept, which is why they are in the camps. Bhutan has amended its laws to dispossess the second category and wants to wash its hands of them by involving Nepal. This may be possible under Bhutanese laws, but not under international law.”

For all of Bastola’s clear-headedness, so lackadaisical has been his team’s approach to the talks that some believe that Nepal could be persuaded to forget rights and wrongs and accept a substantial number of refugees as its own. “If Nepali officials can accept those categories, anything is possible,” an Indian official says with a knowing smile.

It is the constant worry of the refugee that Kathmandu and New Delhi will make a deal over their heads and seek a ‘practical solution in the face of Bhutanese obduracy. As one leader said, “It is immoral and vulgar to think of a compromise on the numbers. The Government should take back all who are Bhutanese and not accept the rest. Let it be on principles and not convenience.”

In July 1992, Prime Minister Koirala got an all party consensus and go-ahead for a three-step strategy under which if bilateral talks failed he would approach India, failing which he would ‘internationalise’ the problem. Stuck on the first rung, he has been unable and unwilling to go further. Available diplomatic and political channels with. India and overseas governments have not been explored. It is clear that Koirala and his party colleagues do not want to waste the goodwill they have in Indian corridors of power for the cause of Bhutanese refugees.

Timid Kathmandu bureaucrats and uncaring politicians are unwilling to go to stage two (with India), or leapfrog to the stage three (internationalisation). Meanwhile, Thimphu is active on both fronts, ensuring Indian non-involvement and internationalising the issue in its own favour.

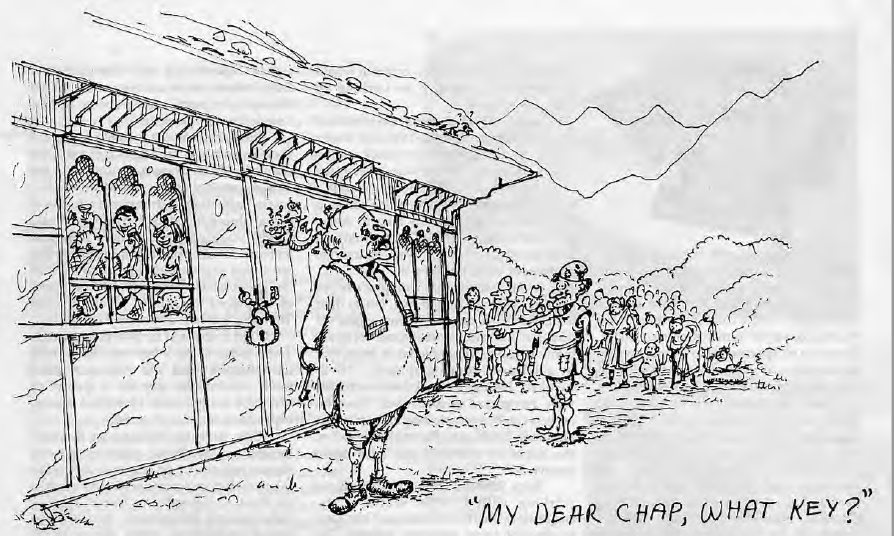

Bhutanese Mohani

Thimphu respects only New Delhi, and only P.V.Narasimha Rao can pressure King Jigme into accepting the return of those refugees that international norms would recognise as Bhutanese citizens. India, indeed, holds the key to the Bhutanese crisis but is unwilling to use it. Why?

To begin with, both the Nepali Embassy in New Delhi and the refugees have failed to lobby Indian politicians. (The refugee issue has only been raised once in the Indian parliament, in the Rajya Sabha). With the politicians out of the picture, it is the men from the ministry who are articulating the Indian policy on Bhutan.

A senior South Block official defends India’s unwillingness to jump into the fray, saying, “You see, India used to be a non-status quo power back from the fifties through the seventies, which is when you saw the Sikkim affair. Today, India is a status quo power and does not have much stomach for adventure in the neighbourhood.”

In full agreement, former Foreign Secretary Dixit maintains that India is tired of being called a hegemonist, and Bhutan apparently serves as the pilot case for trying out the new Indian live-and-let-live policy (see accompanying interview).

Delhi-based correspondents who approach the official South Block spokesman are brusquely told that the problem is a bilateral matter between Bhutan and Nepal. According to a Nepali diplomat, the desk officers in South Block “do not even want to discuss the subject when we try to raise it. It is as if the Bhutanese have cast as spell on them.” (“mohani lagaeko jasto chha.”)

This mohani must be potent, for Indian officials as well as Dixit profess to believe that King Jigme is capable of using the “China card” — a tilt towards Bhutan’s northern border — hence the need to treat him with extra deference. When it is proposed that India should get involved because Foreign Minister Dawa Tsering maintains that most of the refugees are actually from the Indian Northeast, Dixit waves it aside with an easy but the Bhutanese never told us so’.

When Bhutan refers endlessly to its fears of being converted into “another Sikkim”, Indian officials seem willing to overlook the fact that this is a charge which sticks more on India than on Nepali-speakers, and Nepal is not even in the picture. If Bhutan were to be “another Sikkim”, it would be New Delhi that would make it so, probably using the Lhotshampa as a tool for the purpose. (No one seems to have considered that geographically, and demographically in terms of spread of Nepali-speakers, a north-south Sikkim and an east-west elongated Bhutan are quite distinct. Swamping of the deep northern valleys by the midhill Lhotshampa population appears unlikely.)

at his party’s opening.

But there must be more substantial considerations for humouring little Bhutan than because it is a pristine holiday spot with traditions of generous hospitality and gift-giving. Indeed, a Bhutan that is beholden to India (for looking the other way on the refugee issue) can be pressed for advantage. In international fora like the United Nations, India once again has Bhutan’s vote firmly in its pocket. Thimphu will hardly be inclined to side against New Delhi, as it did in 1979 on the question of Kampuchea. It was King Jigme that did Narasimha Rao’s bidding in 1991 when he scuttled a SAARC summit meeting by giving an excuse and staying away.

There are advantages in other areas as well. Bhutan’s economy will now be irreversibly linked to India’s as a result of the hydropower projects on which agreements have been rushed through over the last two years—the Kurichu, Chukha Two and Three, and the Sankosh. Meanwhile, India’s military continues to have unhindered right of passage over Bhutanese territory and air space.

The 1949 Indo-Bhutan treaty binds Thimphu to the guidance of India in its international affairs. While Kathmandu analysts tend to ascribe great significance to this proviso, Dixit and his colleagues are amenable to an extremely loose interpretation (see interview).

Ironically, the guidance proviso was included in the treaty so that India could manage Bhutanese affairs, and not for India to be forced to take responsibility for Bhutan’s misdemeanours. Whatever the intent, however, a clear reading of the lines shows India to be dutybound to have a position on the present crisis.

But then, incongruously, it does not serve Nepal’s long term interests to push this tight interpretation of the treaty as it seeks Indian involvement. After all, there are only two Himalayan kingdoms left, and it is better for Nepal to have a fully sovereign Bhutan by its side rather than one bound by a restrictive reading of the 1949 treaty.

South Block’s inaction on the refugee question is also linked to the absence of pressure from the Nepali/Gorkhali regions of India. Nar Bahadur Bhandari, champion of India’s Nepali-speakers, kept quiet on the Bhutan evictions while he was Chief Minister, although since his ouster in May he seems more willing to speak up. Subhas Ghising, Darjeeling’s strongman, does not want to offend a New Delhi which props him up against the West Bengal CPI(M) government. Meanwhile, Chief Minister Jyoti Basu would not be caught lifting a finger to help Nepali-speakers anywhere who would compete with the Bengali presence. Besides, as he is said to have exclaimed to Nar Bahadur Bhandari when conversation turned to King Jigme, “No, no, he is a good man!”

“The bottom line is that India will not act because Bhutan does not want India to act,” maintains Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) academician Mahendra Lama. His point is confirmed by what the South Block official has to say: “The Bhutanese have convinced themselves that their survival is at stake. The strength of their feeling itself makes us not want to do anything. We would not get into the business of trying to run Bhutan. Besides, they have built up such an image that it would be a public relations disaster for India.”

The Bhutanese themselves are exasperated with all the talk of the need for Indian involvement. Says Ambassador Nado Rinchhen, “When Nepal and Bhutan have a bilateral dialogue going, we should give it chance to succeed. The leadership in the talks must ensure that no vested interest or external force will undermine it.”

His Majesty’s Voice

Journalists and scholars who are invited for guided tours of Thimphu and environs continue to surface with glowing accounts of King Jigme Singye Wangchuk: his humility and sensitivity, his commitment to Drukpa national identity, his concerns about accelerated modernisation, and his eco-friendliness.

Says a Western writer who was in Thimphu recently: “When I spoke to Foreign Minister Dawa Tsering and Home Minister Dago Tshering, there were clear ethnic overtones. It was quite blatant. But then you walk into the King’s presence, he is very rational and articulate, and probably more sincere than his officials. Here is someone who has more than the usual person’s desire to protect his country.”

JNU’s Mahendra Lama, who was recently in Thimphu meeting all the important people, agrees, “The King himself is in the liberal faction. He is very accommodating.” J.N.Dixit believes that without the King’s moderating influence Bhutanese are liable to be “jingoistic”.

But all this appreciation notwithstanding, the events since 1988 cannot be explained in the absence of King Jigme’s directing hand. By and large, in interviews the monarch tends to speaks of higher values white leaving it to Minister Dawa Tsering to present the propaganda. However, the king gave himself away in interviews to Delhi papers during a January 1993 visit, when he spoke combatively of “illegal Nepali migrants who were driven out of Bhutan”, referred to fears of a Greater Nepal, and claimed that the refugees were all communists.

As always happens in the end with dictators and absolute monarchs, “Big Boss” (as he is known to Thimphu bureaucrats) too seems to be succumbing to false feedback. Elaborate preparations are made before the king makes his well-publicised forays into the districts. Underlings ensure that His Majesty hears what His Majesty wants to hear, which is that all is fine with the kingdom, and would in fact be better were it not for those ngolop traitors.

And so, when he visits the South, the Lhotshampa subjects tell King Jigme that they want to stay when they are all packed up to leave. In the East, the Sarchop peasants vociferously condemn the southerners when they really want to talk about forced labour, conscription, and the lack of development works.

While resident representatives of donor agencies might thank their careers for bringing them face to face with a real-life king this late in the century, King Jigme is not as ‘royal’ as many outsiders believe.

Says a Bhutan scholar, “The present-day monarchy is an usurped position, put in place by the British in 1907. The true divine sanction rests with the Shabdung, which is why for safety’s sake Indian officials spirited him away to Manali.”*[Several officials, scholars and refugees (those with families ‘inside’consulted for this article wished to remain anonymous.]

Back in the 1970s and 1980s when there were no difficult decisions to be made, King Jigme was liberal-minded and regarded by all, including educated Lhotshampa, as benevolent and well-meaning. He appears to have changed course about the year 1985, and this became obvious in the harshness with which he chose to impose the Driglam Namzha cultural code on the southerners, the unfair implementation of the 1985 citizenship law, and finally, the way he oversaw the ridding of a seventh of his subjects, who once used to receive Dasain Tika from him—the ultimate bond of a Nepali subject and monarch. The responsibility for what has happened to Bhutan is the king’s own, and not to be shared.

Rongthong Kunley Dorii, who in June this year founded the northerner-only Druk National Congress, does not buy the arguments which absolve King Jigme. “The country, A to Z, is the King’s to rule,” he says (see interview).

What seemed quaint and charming just a couple of years ago, today is looking less benign. The King’s marriage in 1988 to four sisters, by whom he had eight children by the time of bethrotal, must be seen for what it is: not a traditional convention in a polygamous society, but a marriage of convenience arranged by the senior queen and her father so that the monarch stayed within the family. While polygamy is sanctioned by Ngalong society, it is not a present-day societal more.

If the King’s in-laws were not part of the political problem in Bhutan, and if they had not developed into avaricious economic exploiters of the country’s resources, the matter of the royal multi-marriages might be left alone as nothing more than a story of strong desires. But many observers believe that the political and economic shenanigans of the in-laws have had a direct bearing upon the life and times of King Jigme’s country and subjects.

By and large, the refugees wish to let bygones be bygones, knowing that for the moment King Jigme alone has the power to bring about a rapproachment within Bhutan. Says Om Dhungel, a former bureaucrat who is involved with the Human Rights Organisation of Bhutan (HUROB), “He should be able to do it. Big Boss is getting feedback that the public is behind him, and it will be too late by the time he realises it is otherwise. His Majesty should realise that the Thimphu hardliners are all bluster and no substance.”

Says the Bhutan scholar quoted earlier: “The king must understand that the elites will not lift a finger if India decides that things must go differently. Thimphu worships the power of the stick. These people are watching very carefully for a shift in the wind.”

The world sees a kingdom in the clouds ruled by a benevolent monarch; a closer look, and King Jigme’s invincibility seems in question, and the clouds are looking somewhat frayed.

Militancy or Assimilation

If one were to compare some other prominent refugee situations with that of Bhutan, the Lhotshampa appear to be un-inspired. Most of them are impoverished peasants caught unawares with their lives shattered and themselves atop Tata trucks headed for the Nepali border. Do these refugees have the staying power to wait out 40 years like the Palestinians in the refugee camps in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon?

Nor has the refugee leadership been able to inspire them. While the mass is all peasantry, the leadership is middle-class, which prefers to live in adjacent Nepali townships and Kathmandu rather than in the camps. Two years ago, the refugee netas appeared to have the potential to emerge as powerful players. Instead, they have fallen upon each other, heading fractious paper organisations which have lost even the leverage they had in 1992. This discord is sweet music to Thimphu’s ears.

R.K.Budathoki of the Bhutan Peoples Party (BPP), a key player among the dissidents, agrees that “the Thimphu Government is not afraid of us because of our disunity.” Shiva Kumar Pradhan, of the Peoples Forum for Human Rights, concedes, “We have disappeared into Nepali politics and have not focused enough attention on lobbying in New Delhi and elsewhere.”

Ravi Nair is scathing in his comments: “They have done practically no lobbying. Ages ago they should have been filing complaints with the Human Right Commission’s Sub-Commission on Minorities and Discrimination, with the Special Rapporteurs on torture, forced evictions, disappearances, and with the Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. They should have used the ILO mechanisms and submitted memoranda to the political counsellors in the New Delhi embassies before the Bhutan Aid Consortium meetings.”

With a vacuum in the place where leadership should be, how will the refugees situation develop? Observers believe in one of two directions: if the Bhutan-Nepal impasse remains and the quality of life in the camps begins to dip due to reduced aid, frustrated camp inmates, particularly the youth, might turn militant; or they may abandon the refuge camps to join the Nepali diaspora of South Asia, angry youth and all.

Militancy becomes the ultimate weapon of a dispossessed population when it sees no resolution in sight. Bhutan’s national weekly Kuensel, at least, firmly believes in this, providing constant report of violent incidents involving ngolops with their base in the refugee camps. These ‘Kuensel terrorists’ invariably give themselves away for what they are—robbers—when they loot Lhotshampa households rather than going for government offices and installations.

The Lhotshampa population in the camps is not the stuff of passion. The unexposed peasants will not pick up khukuri, and the youth appear to have neither the ideological fervour nor the firebrand leadership that would mould them into guerillas. Further, as a Kathmandu-based diplomat says, “There is not one intelligence agency in the world that would be interested in funding an uprising by Bhutanese Nepalese.”

Neither does India seem too perturbed that Lhotshampa-instigated violence would affect its sensitive chicken-neck in the Duars—gateway to the super-sensitive seven northeastern states. “No, insurgency is not a major fear,” says an official. Even if the Lhotshampa were to take to arms, J.N.Dixit told Himal, New Delhi would deal with the situation as if it were an internal problem of India, crushing it.

As for assimilation, Thimphu’s hopes ride on the single thread that, left to their own, the 86,000 camp residents might yet disperse. Such an outcome would not be too burdensome on either Nepal or India, and would leave a demographically “well-balanced” Bhutan. Bad luck that the refugees were recognised as such, but Thimphu expects that by prevaricating in the bilateral talks and whittling away at UNHCR’s resolve, the hopes of dispersal can once again be revived.

Bhim Subba, a former senior official working with HUROB, scoffs at the suggestions of easy assimilation. “You have to abandon these simplistic notions. The history of en masse Nepali migration is only to areas where land is available. These hill peasants know only how to till the soil, and we know no one is going provide land in India or Nepal. These villagers have nowhere to go but back to where they came from. Even if it is living hell, they will stay in the camps.”

Yankee Support

It has thus far meant little politically for the refugees that the greatest power on earth is firmly on their side. Two consecutive human rights reports by the United States Department of State have lambasted Thimphu for human rights abuses and for its evictions programme.

Robin Rafael, US Assistant Secretary of State for South Asian Affairs, arrived in the camps in March to express support for the refugees, and pointedly referred to the Indian role in facilitating the transfer of refugees to Nepal through Indian territory. In June, Sandy Vogelgesang, the new American ambassador to Nepal, told the refugees that resolution of the refugee problem must be “in line with international law and principles of displaced persons”—precisely what Thimphu wants to avoid at all cost.

That is about as far as it goes, though. The Americans have been content to hold the refugee’s hand and offer sympathies (and, incidentally, pay for a quarter of UNHCR’s roughly U$ 13 million annual expenditure on the refugees).

“We have no leverage on Bhutan,” laments a US official, pointing out that Bhutan and the US do not have diplomatic relations. But the Americans do have a handle on Bhutan, through the United Nations Development Programme, which is the largest multilateral donor agency in the country. As a major contributor to UNDP and other agencies and development banks active in Bhutan, the US is in fact well placed to influence Thimphu, without affecting social sector programmes that would hurt the weak.

While Rafael is known to have raised the Lhotshampa matter with Indian officials, the US will not want to seem too meddlesome in India’s backyard. Nuclear non-proliferation is the main American agenda for South Asia. Foggy Bottom would not squander its limited influence with South Block on an issue that Singha Durbar itself is not too preoccupied with. As the Washington Post’s John Ward Anderson says, “The US has no economic, commercial or strategic interest riding on Bhutan. It is only a human rights issue.”

The Refugee Agency

Thimphu’s carefully laid out plan of eviction would have gone like knife through butter, and the whole episode would today have been but a fading memory, except for UNHCR’s arrival. Foreign Minister Dawa Tsering’s exasperation with the refugee agency is easy to understand (see interview).

Thimphu’s plan would be to try to undercut UNHCR’s senior-staff support for the Nepal programme by hard lobbying in Geneva, and it might even work. High Commissioner Sadako Ogata is known to have been impressed with Bhutanese representations and exasperated with Nepali diplomatic inability to even articulate Nepal’s basic position on the refugee affair.

Bhutan’s allergy to UNHCR’s Nepal office has also to do with the fact that the agency has the expertise to conduct the identification and verification exercise to screen Bhutanese citizens from among the refugees. In normal situations when refugee repatriation is involved, governments neutralise the issue by inviting UNHCR to complete the technical details, as has happened with repatriation of Rohingyas from Bangladesh to Burma, or the Tamils from India to Sri Lanka. Thimphu is unlikely to have use for an agency which can do that.

Tahir Ali, UNHCR’s representative in Nepal, says Foreign Minister Tsering’s charge that his office is biased against Thimphu lacks basis. “There is nothing in our work that is anti-Bhutan. Our public statements and positions are fully consistent with what the two governments are doing. We are waiting for the two governments to do business.”

Asked about fears of reduced funding (with which UNHCR supports service-providers like Lutheran World Service and CARITAS), Ali replies: “While it is true we cannot walk away from a refugee situation, the donors are going to ask how long this is going to continue. Week by week this issue is moving to the margins of the international agenda as other crises preoccupy the donors. We’ve already been told by Geneva to pare down our budgets because of needs in areas like Somalia, former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.”

What would this mean? “The UNHCR is legally obliged to stand by the refugees until a solution is found. But the reality is that with donor fatigue assistance programmes begin to fray and weaken. Sooner or later it will happen here, the shelters disintegrate and people start moving out due to pauperisation. Whoever has the option will utilise it and leave the camps. Then the story is over.”

A Druk Party

The Lhotshampa problem which reared up unexpectedly in the late 1980s papered over the existing divides in northern Bhutanese society. These divisions are now re-emerging, under the harsher glare of modem expectations. The unquestioning acceptance of existing hierarchy and role playing, a centuries-old legacy, could not last long in modern-day Bhutan.

The Drukpa durbar is being charged with accentuating sectarianism and regionalism within Bhutan, favouring Kagyu over Nyingma monasteries. Mid-level bureaucrats are unhappy that the king allows higher offices to be dominated by dashes (noblemen) from the western districts — twelve out of 14 ministers, for example, with only one Assistant Minister a Sarchop.

It is likely that the discontent within will be fanned by Rongthong Kunley Dorji’s new northerner-only party in exile, the Druk National Congress. Rongthong Kunley is a prominent businessman of eastern Bhutan, a Sarchop who was jailed for two months and tortured in early 1991 for having raised questions about the Southern Problem and the East’s inequitable treatment. Upon release, he went into exile and has been in Kathmandu for the last two years, concentrating lately, he says, in establishing a network of dissidents within Bhutan.

The new party’s significance lies in its presumed ability to articulate the interests of northerners who are wary of the Lhotshampa, while at the same time antagonised by the Para-and Haa-centricism (two western districts) of the present regime. The new group vies for recognition among those who constitute the present regime’s base.

At its opening press conference in Kathmandu, the Druk National Congress raised issues of concerns of the northern population, which the Lhotshampa parties had not felt obliged to highlight. Thus, Rongthong Kunley protests the increasingly strict Governmental control over Nyingma monasteries, and says that the traditional system of forced labour has become extremely burdensome because of the absence of Lhotshampa labour. Conscription into the militia is another source of discontent, and the eastern Sarchop have gotten wise to the regional disparities in development works in favour of the west and the south. Rongthong Kunley also cites instances of torture and custodial deaths that have occurred in the north outside the framework of the Lhotshampa suppression.

The new party’s main plank is human rights, says its spokesman Chencho Jigme Dorji, a Ngalong. “Since the Lhotshampa problem and its extended fallout, the realisation has also seeped through to the north that we have no human rights in Bhutan, even on paper. We are the only country in South Asia where such a situation exists, and there is no reason we should maintain it for the sake of the present rulers.”

The unspoken mass support for the Shabdung, “Bhutan’s Dalai Lama”—whose present incarnation happens to be a Sarchop—is also potentially a reservoir of support for the new party. Says a Lhotshampa observer, “The Sarchop are by far the largest community in Bhutan, and they are a very sentimental people. The new party has the ability to mobilise them all.”

Realising the ability of the new party in exile (the organisers do not consider themselves refugees) to provide credible alternatives to their own moribund programmes, Lhotshampa refugee groups have all welcomed its establishment, even though it is an exclusive northerner-only party. R.K. Budathoki of the BPP even seems willing to pass the mantle of overall exile leadership to the new party, although it is not clear that the Congress would want such a role. “To do anything within Bhutan, the BPP desires that the leadership should be Drukpa. And Rongthong Kunley has the ability to bring the people together, and hence at this time we are willing to stand behind Rongthong Kunley,” says Budathoki.

Why this alacrity to welcome the new party? Says one refugee, “Our struggle is seen -as a merely a reaction to what is happening to us. Whereas a reaction from the east and west would constitute a studied attack on the regime’s legitimacy.”

Thinking in Thimphu

When members of the Thimphu aristocracy propose that everything they are doing is to protect the Bhutanese way of life, it is clear that they are, in the main, trying to safeguard their own positions of privilege.

The Bhutan scholar, who has studied Thimphu as a social scientist, is unrelenting in his indictment: “Aided by the West’s glorification of their culture, the Drukpa are mistaking feudal background for religious fervour. If the Drukpa elites were religious, they would give their right arm to protect the system that they have. Instead, they use rituals for the sake of political expediency and have become bullies, a feudal people. A sense of moral conviction and Buddhist sacrifice cannot exist when you have all that power.”

Historically, as in other feudal societies, anyone who represents dissent has been regarded with contempt. This was true with the Ngalong dissidents who fled to Nepal in December 1964, and is even more true today of the attitude towards all exile leadership. There is a sense of betrayal, and blind anger against these deserters. With such a mindset, there can hardly be any trust, or ability to recognise moments of grave political peril.

The seething resentment against the Lhotshampa, in particular the refugee leaders, is very close to surface. This keeps Thimphu society, in the rush to pronounce judgements on ngolops and namak-harams, from comprehending why a dasho should leave a privileged position in the Royal Government to seek a life of refuge. It is such resentment which leads Ambassador Nado Rinchhen to express perplexity: “Some may believe us and others may not, but there are people who really wanted to leave. We try to keep them, but they go anyway.” (The ambassador, at least, should try to understand. Rinchhen was one of the 1964 exiles and spent many years in Kathmandu before being pardoned and reinstated in high position.)

The Washington Post’s John Ward Anderson says the high-ups he met in Thimpu “seem to believe in their own spins”. He adds, “It is not such a huge acknowledgement to say that there were some mistakes made, but they do not do that. In speaking of protecting their culture, they have picked up the perfect issue. If they said they were protecting their monarchy or their privileged status, there would be no buyers.”

Says Michael Hutt, of the School for Oriental and African Studies in London (SOAS), “Far more people know what has really happened in the south than one would think. They are aware that solving the crisis, that is letting the refugees back in, might constitute a threat to Bhutan. When I meet Bhutanese, there is a sense that mentioning the Southern Problem is considered ill-mannered, and that the subject is distasteful. The crisis should be left to run it’s course, its a regrettable but necessary process,’ and so on…”

It often happens that the mirror to closed-in Third World societies is held up by Western academics who are able to provide the objectivity of distance and scholarship. “But the Bhutan case has shown how spineless and intellectually dishonest the Himalayan academic community is,” says a diplomat in Kathmandu.

Michael Hutt of SOAS, who organised the only international conference on the Bhutan crisis thus far in March 1993, and who has written several papers on the Southern Problem: “Bhutan has retained the loyalty of a select band of foreign academics who seem to swallow the ‘voluntary emigration’ and ‘cultural swamping’ arguments whole, apparently without question. These academics are fiercely protective of Bhutan, and constitute an important factor affecting Bhutan’s judgement of the validity of its case.”

With both outside media and academia remaining silent (and a severe dearth of indigenous journalists and scholars), there is nothing to temper the Thimphu aristocracy’s contempt for all opposition and its self-righteous belief in the primordial right to culturally cleanse the country. To their own detriment, the rulers will be oblivious to reality when the ground begins to shift.

Democratic Bhutan

While Lhotshampa refugees and northerner exiles emerge from Bhutan to speak bravely for human rights and democracy, is it likely that they have a silent following within, even if not among Thimphu’s superelite? Not if the population believes what King Jigme believes. He told Christopher Thomas of the Times of London in April: “But Bhutan has a very democratic monarchy. Most people think a country with a monarchy is backward and feudal. But Bhutan is more democratic than most democratic countries and definitely more democratic than any democratic Third World country.”

The reality is elsewhere. Bhutanese polity is today balanced like a house of cards. A nudge or slight breeze and it could collapse all around King Jigme, and it will be more than the tragedy of one man. It will be the collapse of a polity that has much going for it.

Bhutan has among the best socio-economic indicators in South Asia, finely developing health and education programmes, and administrators capable of planning ahead and acting on their plans. But none of the benefits will accrue in the long term if newfound political desires are suppressed rather than channelled. Howsoever safe, sanitised and “democratic” King Jigme’s system might be in comparison to, say, Nepal’s disorderly democracy, he cannot now escape being sucked into the spiral. He must fashion a system that can maintain today’s development momentum while providing more political space for his subjects.

Rather than philosophise endlessly to wonder-struck visitors, the king should have years ago initiated work on creating a polity where power and economic largesse was shared among Bhutan’s three main communities and regions. Acting on his own initiative, he would been able to control the flow of events, whereas now it is fast becoming an all or nothing game.

The responsibility to do something lies with King Jigme because it was he who, by inaugurating the drastic action in the South, brought forward the political awakening of his subjects (of both southerners and northerners) by at least a decade.

Whatever may happen to the refugees, the Druk Gyalpo can look forward to a future of internal dissent — regional, sectarian and class-based. The dissent will come not only from the northern population and repatriated refugees, but from the tens of thousand Lhotshampa that have remained behind, whose psyche has been disturbed.

Externally, what appears to be India’s rock-solid support could dissipate like mountain clouds in the evening. If New Delhi decides that Bhutan’s instability jeopardizes its sacrosanct Northeast equation, or if it sees it in its larger interest to mollify a restive Nepali-speaking population of the region, it will act without care or concern as to what King Jigme desires.

Says an Indian official, choosing his words carefully: “There has not been a pronounced shift of power (in Bhutan), so why knock it?”

The heightened state of unease of these last few months in Assam, Arunachal and Nagaland is harbinger of a break in the regional equilibrium. When that happens, Home Ministry concerns rather than those of South Block will begin to dictate policy. At that time, there is no saying which way the cards will fall.

“The Bhutanese King should have no illusions. India will act on its own interests,” says Rishikesh Shaha, scholar and elder statesman on Nepal. “Back in 1950, Mohan Shumshere came back happy to Kathmandu when New Delhi plied him with assurances. Overnight, he was out of the door.” The reference is apt in more ways than one, for Bhutanese polity, economy and environment are today where Nepal was placed at the end of the feudal Rana era.

India has several options to exercise should it believe that its security interests are affected by a suddenly unstable Bhutan. These extend from reinstating the Shabdung at one extreme to engineering a Sikkim-like putsch and adding a state to the Union at the other. More likely, however, India would enforce a ‘pragmatic’ solution by negotiating a tripartite division of the refugees, and dictating a new political structure under the king that takes account of the political realities within the country.

Better for King Jigme to seek these solutions himself. It is still in His Majesty’s hands to design a forward-looking system which is inclusive of the three communities and regions of Druk Yul—the west, east, and south.

Note to Readers: When writer K.M.Dixit applied for permission to visit Thimphu in order to research this article, Foreign Minister Dawa Tsering wrote back saying “…it is difficult for me to clear your visit to Bhutan at this juncture”, because Himal’s coverage of the Southern Problem had been “highly biased and one-sided”. When a similar application was made for Himal’s Jul/Aug 1992 issue, the response had been “,..your visit to Bhutan at present is not convenient to Royal Government.”

Kathmandu and Thimphu

When Nepalis of Nepal disparage the Bhutanese Government for what it has done to Bhutanese Nepalis, it helps add to perspective in Kathmandu by looking inward. The Thimphu attitude towards the Lhotshampa is akin to the Kathmandu-based Pahadi’s resentment of the Madhisay of the Tarai. While there are obvious areas of dissimilarity, here too, the issues are of a plains population that represents a larger ‘diaspora’ in the Ganga plain; an open border and earlier migration into unsettled lands; and fears of cultural swamping. Not to forget the fundamental difference, however: Thimphu applied a programme of depopultion to correct a perceived historical wrong, whereas Kathmandu could not, or would not.

Garganda to Beidangi

Did the refugees make a grave mistake back in 1990 by being persuaded to enter Nepal, thereby ridding India of a problem and the need to resolve it? Among those who think so are Darjeeling politician Madan Tamang, JNU Associate Professor Mahendra Lama, and New Delhi human rights activist and documenter Ravi Nair.

R.K.Budathoki of the BPP, however, recalls that the refugees clung on to makeshift camps like one in Garganda in West Bengal and Assam until it was impossible to stay on due to lack of food and shelter. Says Bhim Subba, of HUROB, “If we had stayed in India, there would have been no refugees left today. We would have been like the millions of Bangladeshis in India, part of the South Asian diaspora. It was the very act of coming to Nepal that kept the refugee’s problem alive and that today we survive as refugees in the Beldangi, Pathri and Goldhap camps.”

The view from South Block

India’s policy-maker on Bhutan has been the powerful, say-it-like-it-is J.N. (“Mani”) Dixit, Foreign Secretary till end-January 1994. It was during his watch that the Southern Problem peaked. Dixit regards himself a friend and mentor of King Jigme, who was a child when he served in Thimphu as development advisor. The former Foreign Secretary was just back from a Thimphu holiday when he spoke to Himal at his house in Gurgaon, Haryana.

On the origins of the Southern Problem: The ethnic demography of Bhutan is characterised by inevitable dichotomy. Tibetan stock in the high valleys and ethnic Nepalis in the foothills. The Nepalis were more urbanised, economically active and politically conscious. They began to be an intrusive and active factor in Bhutan’s socio-economic scene. The assertion of the Nepali sense of self had a political fallout in Bhutan. The gradualness of political liberalisation would be accelerated uncontrollably, and the King’s base among the Northern Bhutanese would be eroded. The authority of the Advisory Council, and of the monarchy itself, might be eroded. All this made him strict and generated some demands of the Nepali community, which in turn revolted, and the response was drastic, and the Nepalis left the country.

On the Bhutanese mindset: The Nepalis’ status in Bhutan was the result of a very informal arrangement. There is collective socio-cultural paranoia in Bhutan, which is a very insulated society. It is a majority with a minority complex. It is like the Sinhala fear of the larger Tamil diaspora of 16 million in Tamil Nadu and eight million in Malaysia. The Bhutanese, similarly, fear the Nepali diaspora.

On King Jigme: I have known the king since he was seven or eight. He has discussed the problem when I was Foreign Secretary. I do not see any animosity towards Nepalis. He is worried about a polity that is trying to jump 300 years in 25 years. The king is perhaps a moderating and reasonable factor, and if you took him out the average Bhutanese would probably be much more jingoistic. He is deeply conscious of Nepali entrepreneurial abilities and of their exposure to the Bihar and Bengal culture. The king should be allowed to run a stable government.

On India’s possible involvement: Delhi is averse to getting involved because our national experience in terms of demographic pressures on the Indian Republic, especially in the last 15 years, has been very critical. We, have had problems with Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, even Afghanistan. We do not want to get involved in a controversy. Because of our larger size, regardless of rationale, it tends to get interpreted as a facet of hegemonism. Prime Minister (Rao) has told Nepal, that the only advice he can give is to talk and settle the issue in a reasonable manner. 85,000 to 100,000 is not a large number.

On possible militancy from among refugees: If there is a move towards militancy, India would take firm and decisive action. Rather than ask the Bhutanese to take back the refugees, it would be more likely that we would suppress militancy. India’s interest would be to quash it. We will not allow something that has a bearing on internal security to be resolved by resorting to diplomacy.

On Bhutanese claims that many refugees are actually from the Indian Northeast: The Bhutanese have not told us that the refugees are from the Northeast. The borders are both open, and it is difficult to regard them as refugees.

On the 1949 Indo-Bhutan treaty:The treaty obligation states that Bhutan “shall be guided”. In the past, India’s interpretation might have been overarching, but the reality is that “His Highness” became ”His Majesty” along the way. Progressively, Bhutan’s United Nations membership, its international memberships, etc. meant that the interpretation of the content is not what it was originally.

On India mediating between Bhutan and Nepal: We are disinclined, because we are tired. Whenever we have gone in with the desire to help, we have always been criticised. When Tribhuvan came to India, and we restored his monarchical power, that was not appreciated. We go to preserve the integrity of Sri Lanka and immediately we are labelled interventionist. We rescue the Maldives from insurgents and the rest of the region is antagonised. Bhutan has contacts all over. The China card, the potential access to Tibet, is still there.

Rongthong Kunley Dorji

Establishment of the Druk National Congress—the exclusively Sarchop and Ngalong party—was announced in Kathmandu on 21 June. Its founder is Rongthong Kunley Dorji, a prominent Sarchop businessman from East Bhutan who emerged from a two-month incarceration in 1992 to livein exile in Kathmandu.

On King Jigme: The king himself created the problem in the south, and he must think deeply and try to solve it. He has brought, about divisions between the Ngalong, Sarchop and Lhotshampa. He has brought about divisions between the Kagyu and the Nyingma, discriminating against the latter.

Do not judge a book by the cover. The country, A to Z, is the King’s to rule. A lot of money is, spent spying on the people and the top-level bureaucracy. There is an atmosphere of fear, created by Kunpas, or informers. The king knows everything, but he has many tongues with which to fool the reporter or the diplomat.

How can you call a marriage to four wives traditional? Bhutan’s old kings have never done what this king has done. He has shamed the country in front of the world.

About development in Bhutan: When visitors Come, the Bhutan Government will show them Paro, Punakha and Thimphu, all the advanced districts from where the high government officials come. But, go to Kurtey, Mongar, Tongsa; in the villages you will see true poverty. The Bhutanese king thinks only those who know English are advanced.

On hardships in Bhutan: There is forced labour (goongda woola), made all the more difficult because of the absence of the Lhotshampa. It is hard to till the fields. The militia is conscripted, and whoever shows any reluctance is called ‘anti’. There is also disgruntlement in the civil service. If you are related to the king or the senior people, you are automatically in a senior position. The northern Bhutanese population wants, to talk about all this, but is not allowed.

On his party’s plans: Our plan is to sensitise the population about human rights—what other countries take for granted and what we do not have.

On the Indian stance: The Indian Government must understand that it must not blindly support the king, for the public will then become anti-Indian.

On the Shabdung: The Shabdung is India’s trump card with the King, in case he does not do their bidding. If you took a vote today, the elites would vote for the Shabdung. The king is seen as just an ordinary person. If the king, does not form a constitutional monarchy, it will have to be a choice between the Shabdung and the king. In Bhutan, we must separate religion from politics. Meanwhile, our party will certainly received support from the power that resides with the Shabdung.

“I Don’t Know”

It was clear that the people knew something but were afraid to talk. They all agreed that many had left, but were unwilling to say why. This was the refrain of 10 or 12 people I met.

‘Are you Nepali?’

‘Yes’

‘How long have you lived here

‘All my life.’

‘Have many left?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know.’

I only saw blank faces and heard the ‘I don’t knows’.

-John Ward Anderson of The Washington Post, recalling a tour he took of Samchi District, with Government escort, in Bhutan’s south in April.