From The Wire (April 20, 2023)

This is part one of the two-part ‘India in Nepal’ series. Read the second here.

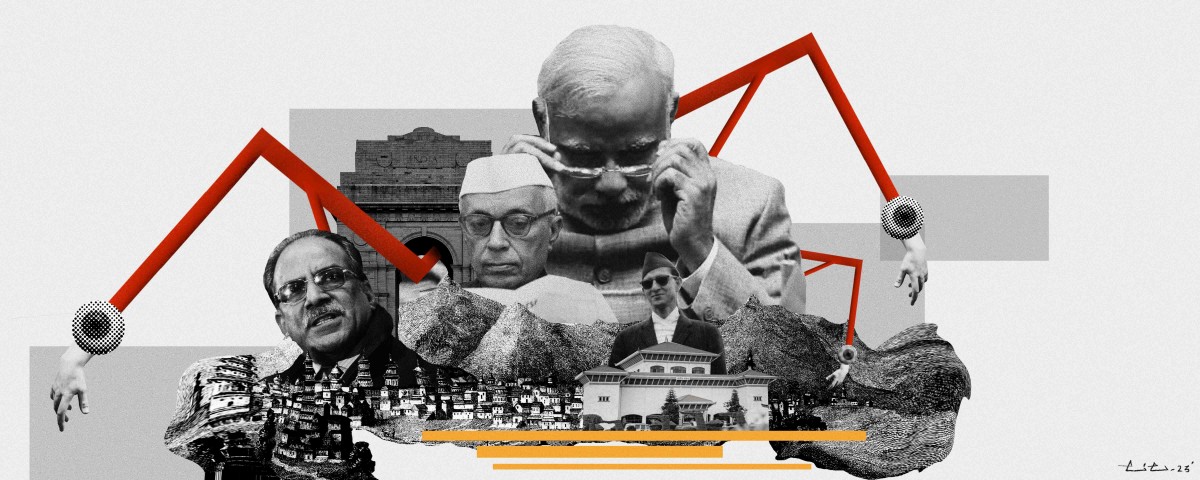

New Delhi’s escalating interventionism rankles Kathmandu and flies against India’s self-interest in a stable and successful neighbour. Timid when confronting world powers, New Delhi is actively working on manufacturing consent in Kathmandu.

As with other diplomatic missions of India, the tagline used by the Indian Embassy at Lainchaur, Kathmandu, is ‘India in Nepal’, meant to describe cooperation in economic, developmental and cultural spheres. Were it that the involvement of India ‘in’ Nepal were that benign, for it is a relationship that since the 1950s has been marked by intervention in politics and governance. And there have been no lessons learnt by New Delhi over numerous escapades of micro- and macro-management – both covert and overt – as a result of which Nepal has evolved as a sullen neighbour when it should be the friendliest of all.

Over the last half-year since the November 2022 general elections and subsequent formation of government and election of a new president, New Delhi’s involvement has attained fever pitch. The fulfilled desire has been a ‘manageable’ coalition of the Nepali Congress (NC) and Maoist parties and confirmation that the former got its choice of the new President of the Federal Republic. Although meddling has been the rule, the past half-year reminds of Indian activism in the final days of Constitution writing in 2015.

Delhi Durbar

Nepali citizens have been granted the boon of short memory in order to cope with earth-shaking developments that occur with appalling regularity – ‘people’s war’ to palace massacre, earthquake, cloudbursts and blockade. Amidst all this, there is risk of New Delhi’s strong-arm tactics being regarded as part of a ‘new normal’ by Kathmandu’s civil society custodians, who in any case are limiting themselves to whispered grumblings.

Before India’s Independence, there was an arrangement between the Rana oligarchs and British rulers that Nepal would remain sovereign but subservient, and the arrangement worked well for satraps on both sides. The British support for the Ranas shogunate was the reason Bisweshwor Prasad Koirala (‘BP’) and fellow revolutionaries decided to make common cause with the Quit India freedom-fighters. They agitated together, shared bread in jail, with the Nepali leaders confident that Indian self-rule would end the era of deference to Delhi Durbar.

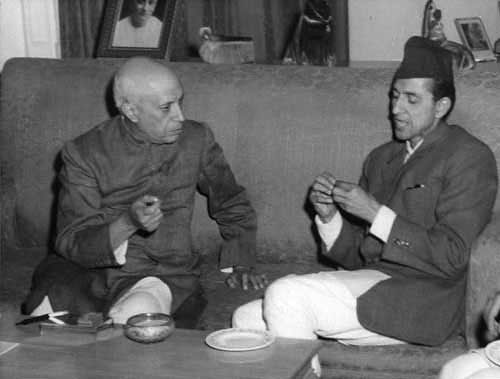

Upon Jawaharlal Nehru becoming prime minister, and while the revolutionaries were still fighting the Ranas, Koirala witnessed a fellow rebel transform into head of government with revised geopolitical and interpersonal calculations. While among his peers Nehru had stood up for Nepal’s sovereign status in 1947, Koirala discovered that the expectation nevertheless was of a country under Indian umbrella and hegemony.

Koirala’s rude awakening was in 1950 when he landed in New Delhi on a DC-3 Dakota aircraft with money looted from Rana customs at the Birgunj border. He was surprised to be greeted at Safdarjung Airport by a military cordon ordered by Nehru, and was escorted to the Prime Minister’s presence at Teen Murti House.

In Atmabrittanta: Late Life Recollections (1998), Koirala recalls a livid Nehru confronting him, and how Nehru was transforming from revolutionary to prime minister, with attendant exigencies.

In January 2023, American researcher Daniel W. Edwards reproduced in the Nepali Times weekly a document from the US Department of State Archives, the US Consul General in Calcutta reporting on an October 15, 1953 conversation with Koirala. At that time, BP’s elder half-brother Matrika Prasad Koirala was prime minister as Nehru’s choice. BP confides that Nehru had turned cold on him over two meetings that August:

“At both meetings when [Koirala] endeavored to point out to Nehru the errors which the Indians were committing in Nepal in the implementation of their policy, he was cut off short and told that because of geographic location Nepal was going to have to develop under the aegis of the Government of India. BP tried to point out that Nepalis were slowly but surely developing a nationalist spirit, that this nationalist spirit could be channeled into agreeable Indo-Nepal relations which could be mutually beneficial to both countries… BP claims to have very drastically revised his opinion of Nehru over the past year and a half. He said that in mid-1951 he had been warned by Jai Prakash Narayan that he, BP, was putting much too much trust in Nehru for the good of Nepal. Narayan had continued with a softening remark to the effect that one must not put that much trust in any foreign nation’s prime minister, for countries, like people, are still antagonistic toward each other and try to take advantage.”

Robes in the almirah

Nepal’s struggle since 1947 has been to keep New Delhi out of its affairs, while the latter’s unrelenting effort has been to try and elbow in. The uprising of Nepal’s citizenry against the Ranas was not allowed a democratic denouement when Nehru foisted the so-called ‘tripartite agreement’ (which Koirala claimed never happened) leading to a hodgepodge government of Ranas and the Nepali Congress which prevented the country from starting on a clean slate.

From the get-go of Independence, as they turned towards Nepal, New Delhi’s new rulers donned the viceregal robes left behind in the almirah. There were some successes on the part of Kathmandu, such as getting New Delhi to evacuate 18 military listening posts on its territory and ending the practice of an Indian advisor attending cabinet meetings, but New Delhi never stopped trying to be the major-domo of Nepali raajkaaj.

India’s sway over Nepal can to some extent be ascribed to the pusillanimity of Kathmandu’s party leaders.

During times of political chaos, as between 1950 and King Mahendra’s coup d’état of 1960, they sought Delhi’s favours to get to be head the government. With the royal regime holding politics in its grip for three decades after 1960, New Delhi had less of a leeway, but as the Panchayat autocracy collapsed to the People’s Movement of 1990, the Indians got back to playing favourites among parties and factions.

At the beginning of the democratic era after 1990, even with B.P. Koirala having passed away, the stature of Nepal’s leaders limited the potential for Indian meddling. That these leaders had participated in the Indian freedom struggle provided a security umbrella against excessive bureaucratic and intelligence manoeuvring – a modicum of decorum was maintained. The passing of Girija Prasad Koirala in 2010 removed the last tall leader.

Kathmandu’s political class became fixated on New Delhi as power broker. This was self-inflicted harm, for the relationship was much more dignified and equal earlier with Calcutta, Benaras and Patna. Delhi-centricism became the rule, as exemplified by the NC’s Sher Bahadur Deuba, who as many-time prime minister is besotted with pleasing the south.

In the case of the sitting PM Pushpa Kamal Dahal, New Delhi retains even stronger leverage, going back to his time in Noida safe houses during the conflict years.

For his present-day value, New Delhi apparatchiks seem willing to ignore Dahal’s opportunistic anti-Indianism of the past, as the person who derided India as ‘bideshi prabhu’, and in the waning years of the conflict got Maoist cadre to prepare for an Indian invasion by digging tunnels at the border (‘surung yuddha’). Perhaps the Indian ‘handlers’ always knew they had Dahal in their grip, and indeed the full blown entry of Indian ‘agencies’ into Nepali affairs was only possible when the Maoists came above ground in 2006.

Through the agencies, New Delhi has in particular sought to control the political leadership of Tarai-Madhes, worked to influence Kathmandu by way of manufacturing consent in the plains, and once even pushed the nonsensical ‘ek madhes ek pradesh’ agenda (a 500×20 mile autonomous strip meant as an Indian buffer). Adventurism peaked in 2015 when then Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar came as PM Modi’s special envoy to stall the promulgation of the constitution. Turning off their mobile phones to evade calls from Lainchaur (where the embassy is located), the framers succeeded in adopting the document. A version of that affair was repeated when present Foreign Secretary Vinay Kwatra arrived in early February 2023, ostensibly for bilateral talks with his counterpart Bharat Raj Poudel, but meeting the entire political spectrum including one-on-one’s with PM Dahal.

While Foreign Secretary Kwatra (till recently ambassador to Nepal) has had the run of Kathmandu, Shanker Sharma, the Nepali ambassador at Barakhamba Road in New Delhi, has been cooling his heels since May 2022 and is yet to be granted formal audience with Minister of External Affairs, Jaishankar. Also to be noted is the fact that Nepal’s previous ambassador Nilamber Acharya was among those targeted by the Indian authorities through the Pegasus spyware that hacked his mobile phone.

New Delhi Media and civil society

The Indian government, whether run by the Congress or Bharatiya Janata Party, would not make repeated errors in next-door policy if Raisina Hill did not keep such tight control over the press and intelligentsia with its strictures and press notes. The subservience of media gatekeepers to South and North Block diktat leaves Nepal, along with Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, suffering from intrusion that might otherwise have been softer. If anything, as a prominent Delhi editor wrote in a slightly different context, journalists are ‘force multipliers’ when it comes to India’s geostrategic interests.

Up to the 1970s, Indian papers had senior journalists assigned to Kathmandu, sage intellectuals and litterateurs from the Hindi heartland who knew Nepal for its history and complexities. ‘Nepal studies’ in New Delhi is today manned by academics and researchers who bend with the wind wafting down from the Hill, and former ambassadors who cannot depart too far from the official line. The weak scholarship is surprising, given the importance of Nepal due to the open border, the country adjoining the Ganga heartland, its valuable water resource, the Himalayan ridgeline with China/Tibet on the other side, the cultural intertwining, and the fact that Nepal is the seventh-largest remittance sending country to India, providing income to the poorest in adjacent states.

It is fear of being tarred ‘anti-national’, more so by the self-aggrandising Hindutva ideologues, that has the commentators and academics toeing the statist line. Along the way, the Delhi press scaremongers about Chinese influence on Nepal, to the extent that the larger Indian public is convinced that Kathmandu has sold out to China. As for the slew of protocols that were signed between Kathmandu and Beijing in 2016 on trade, transit, transmission lines, etc., beyond the right of a country to do right by itself, the fact is that they were facilitated by the Indian Blockade of 2015.

The journalists in Patna in particular have over the years been used by the ‘agencies’ to plant stories of third country infiltration into the Ganga heartland via Nepal, mostly false but receiving enthusiastic media uptake. The extreme editorial leeway allowed exceptionally on Nepal matters was exemplified by a Hindustan Times staffer’s op-ed suggesting at the time of Nepal’s constitution-writing that New Delhi use both “overt and covert tools” at its command to bring Kathmandu to heel, adding: “There is little point in being a regional power if you do not exercise it at decisive moments.”

Some online media portals do defy the official dictation on regional geopolitics, and the questioning spirit also picks up as you go southward and eastward from New Delhi, but not nearly enough. Demanding obeisance from journalists and analysts makes for a blindfold that keeps Indian authorities from perceiving the breadth and depth of Nepali opinion. New Delhi think tanks and conclaves have little time for independent-minded Kathmandu commentators, tilting towards individuals who will not rock the Indian boat. Lately, South Block has taken to patronising individuals and organisations that do not have weightage, or even name recognition, in Kathmandu.

The broadcasts of India’s satellite channels on Nepal have to be seen and heard to be believed, in terms of liberties taken. The primary concern of Indian journalists in the immediate aftermath of the April 2015 earthquake was to glorify New Delhi’s relief efforts. Or take the retired ambassador frothing at the mouth, demanding a doubling down on the ongoing blockade, for Kathmandu having the temerity to defy diktat on the Constitution. Then there was the time in June-July 2020 when Indian channels were going wild about the lady ambassador of China having laid a “honey trap” for then PM KP Oli. It should not be forgotten that in Nepal viewers watch Indian television, and supercilious coverage solidifies the image of the ‘ugly Indian’.

Every monsoon, it is a constant for Indian politicians and commentators alike to slam Nepal for ‘sending’ floods into Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, which to begin with shows ignorance of both geography and river morphology. Nepal is said to open the floodgates of dams to inundate the plains even though it does not have reservoirs that can do that, and the two barrages on the Kosi and Gandaki by the border are manned by Indian government personnel.

Open border

Certainly, New Delhi feels the vulnerability of the open border, a frontier that is unique to the two countries but could be misused by third parties to infiltrate the populous underbelly of India. Similarly, India fears Chinese escapades over Nepal’s Himalayan ridgeline, a geostrategic paranoia that harks back to the 1962 debacle. But these two factors in themselves do not justify the continuing programme of intervention: throughout, Kathmandu has been accommodating with regard to the borer apprehensions, and every political scientist knows that modern-day warfare makes New Delhi’s Himalayan obsession redundant.

Further on the unrestricted border, it is Nepali society that has suffered immeasurably more than the other way around from the visa-free passage. Many of the Maoists who picked up gun against parliamentary democracy in 1996 were trained in India and went back and forth with ease for a full decade. Indian territory was in large part the base of operations for the insurgency, for logistics, safe houses, conclaves of commissars and commanders, and entry-escape routes – to what extent can only be known when the Indian officials involved or the Maoists themselves write their memoirs.

In this reading, it is Nepal that has been grievously infiltrated and not the other way around. The best one Indian ambassador could do back in the conflict years, when asked by this writer about Maoists using Indian territory was to respond ingeniously: “Listen, India is such a large country, how do you expect us to find them?!”

Without doubt, the open border is meant for use by Nepali and Indian citizens and not third-country nationals, and on this matter no Indian authority can accuse Kathmandu of not cooperating to prevent misuse. Further, the Nepal-India border should be the prototype for what should ultimately be the India-Pakistan and India-Bangladesh frontiers in a future peaceful Southasia when animosities subside, as they must. For this reason, too, the New Delhi establishment would be advised not to constantly use the open border as a battering ram against Kathmandu.

Please read part two.

Kanak Mani Dixit is the publisher of Himal Khabarpatrika and the founding editor of Himal Southasian.