From The Wire (April 21, 2023)

This is the second part of the two-part ‘India in Nepal’ series. Read the first here.

The most benign period for Nepal’s relations with India was the brief flickering of the Gujral doctrine, which proposed non-reciprocity in dealing with the smaller neighbours in enlightened self-interest. India does not remember Gujral, while in Kathmandu these are the times of RAW and IB.

To become ‘Vishwaguru’ as presented by the Modi regime, a global mentor with geopolitical clout that also comes with being the most populous country on Earth, India needs to expand its economy manifold. As important, New Delhi needs friendly South Asian neighbours that are willing to support its aspirations for the high table. The precondition for this, in turn, is to keep from meddling in the internal affairs of those next door, particularly Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh – Pakistan having been relegated to the position of adversary, if not enemy.

India’s insecurities as a young nation-state born in 1947 are evident in its dealings with Nepal, whose history as a country goes back to the mid-1700s. As a nominally federated country that has carried forward the structures of colonial centralism, India has fallen for ultra-nationalism as the unifying creed, lately coated with a dangerous veneer of Hindutva.

Nepal, with its new constitution, goes against the trend of exclusivist governance in South Asia, even though it certainly has its own issues vis-à-vis Kathmandu-centricism and marginalisation of non-mainstream communities.

China in Nepal

New Delhi spends sleepless nights obsessing about ‘losing Nepal’ to Beijing, the fear that Nepal will go rogue on India. True, China is no longer the remote behemoth that accepted Nepal as being in the Indian sphere of influence, an attitude harking back to Mao-Chou-Deng times. Under the rule of Xi Jinping, Beijing is keen to muscle in on Nepali politics and has been involved in several escapades that have been exposed and challenged.

In 2010, Beijing used a Hong Kong contact to try and provide NPR 50 crore to buy the prime ministership for Maoist chairman Dahal, one crore per 50 MPs. The tape implicating Dahal’s right hand Krishna Bahadur Mahara created a momentary uproar, then he went on to be elevated to Speaker of the Lower House, a post he later lost to a scandal.

More recently, Beijing has gone into overdrive trying to unite the so-called communist parties of Nepal, indicating ignorance of Kathmandu’s political reality and sensitivities. In 2021, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesman thought it appropriate to condemn what it termed ‘coercive diplomacy’ by the US on Nepal regarding a USD 450 million grant to fund transmission lines, whereas he should have shown the courtesy to stay away from third-country matters.

Delhi’s worries about China are exaggerated, however, and for now, northern activism is no match for southern adventurism. True, Kathmandu indulges Beijing in order to have a counterweight to India’s overwhelming presence, but the tripwire will release as and when Beijing oversteps. Meanwhile, New Delhi’s response to ‘China in Nepal’ has been to stoop rather low, such as in refusing to import electricity from Nepal produced by hydropower plants built with Chinese investment or contractors. New Delhi has blocked international flights out of Pokhara’s new airport because it was built with a loan from EximBank of China.

That India does massive commerce with China but wants to checkmate Kathmandu’s own moves points inescapably to an imperial dog-in-manger mindset. India’s leadership should be confident that Nepal’s state and polity will never become ‘pro-Chinese’ to mean ipso facto ‘anti-India’, but it is not.

Beijing’s non-negotiable and primary concern with Nepal has to do with the possible use of Nepali territory to promote instability in Tibet, where Beijing is still not confident of its grip six decades after the takeover. Other than that, Beijing’s rulers appear more than willing to go over Nepal’s head in dealing with New Delhi, with whom they relate and compete on a separate level.

In May 2015, Beijing did not bother to inform Kathmandu when it signed an agreement with New Delhi on the use of the Lipu Lek pass for trade and pilgrimage to Mount Kailash, disregarding Kathmandu’s claims on the territory. The then Sushil Koirala government felt constrained to send a protest note to both governments.

Enter the spook

New Delhi cannot seem to help itself but to interfere in Nepal, even when such enthusiasm flies against the Panchsheel philosophy, creates animus in the target population, and actually harms India’s economic and geostrategic interests. By now the colonial Nehruvian attitude has evolved into the ‘operational activism’ of the Modi era, letting sleuths loose in Kathmandu by-lanes, conspiring in government formation, and engineering the placement of key officials. Such involvement will at best provide momentary tactical gain, while messing up Nepali politics, and preventing democratic stability and economic growth.

Indian adventurism does wax and wane, and the most benign period for Nepal was the brief flickering of the ‘Gujral doctrine’ under the I.K. Gujral government of 1997-98. It proposed that India not seek reciprocity when dealing with the smaller neighbours, not as a sop but in enlightened self-interest. Today, India remembers neither Gujral nor his code. In Kathmandu, these are the times of the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) and Intelligence Bureau (IB) apparatchik, one meant to conduct international intelligence and the other domestic, Nepal getting snagged in the net of both.

In the past, it was the political class of the two capitals that kept in touch, and engagement by New Delhi was relatively transparent, with meeting records, communiques, interviews and published letters such as those between Nehru and the Koirala brothers in the 1950s. But in order to establish a lord-and-minion relationship, New Delhi now deploys the opaque ‘agencies’. There is no paper trail nor accountability for operations conducted, money spent and failures that have accumulated. New Delhi may move on, but Kathmandu is victimised in the long term.

At times, there are exaggerated claims of Indian adventurism, and Kathmandu’s players cannot be allowed always to play the victim and hide behind their incapacities. But the fact is that the spooks have been elevated practically to the role of diplomatic agents – they move about so openly that they might as well be distributing visiting cards.

In October 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi went so far as to send the head of RAW, Samant Goel, as a personal envoy to Kathmandu, forcing then prime minister K.P. Oli to engage with him publicly. True to form, Kathmandu’s chattering classes took this opportunity to lambast Oli rather than challenges India’s Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) for forcing its head spook on Nepal.

The elevation of Indian undercover agents to the level of public players in Nepal has mainly to do with the arrival of the Maoists above ground, and the Nepal-watcher scholar S.D. Muni is a credible source. Muni recounts in a chapter in the book Nepal in Transition: From People’s War to Fragile Peace (2012) how at the height of the insurgency in June 2002, Maoist leaders Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Baburam Bhattarai wrote a submissive missive (the exact Nepali term would be bintipatra) to the PMO in New Delhi, seeking good offices of PM Atal Behari Vajpayee and promising “not to do anything to harm (India’s) critical interests”, writes Muni, who has been close to Bhattarai in particular.

In response, National Security Adviser (NSA) Brajesh Mishra asked the duo to contact the IB and RAW agencies, which they dutifully did and “reiterated their position again in writing”. As a result of the discussions between India’s PMO, IB and RAW, “the intelligence surveillance and restrictions on the Maoists’ movements in India were relaxed”, and “Maoists could now move (in India) with greater ease…”

Later, India facilitated meetings in Delhi between the Maoists and Nepal’s political parties that were agitating against King Gyanendra’s takeover in 2005. The Second People’s Movement surged, Gyanendra was ousted, and the Maoists entered open politics. This was how the Indian ‘handlers’ of the top Maoist leaders came to be key actors in Kathmandu, putting successive accredited ambassadors of India on the back foot, to the lasting detriment of bilateral relations based on diplomacy and political contact.

This reliance on the ‘agencies’ in the case of Nepal is of course part of a broader malaise that has overtaken India’s once-upright foreign service, which under presiding foreign minister S. Jaishankar, has evolved more as a courier service for policy prepared by NSA Ajit Kumar Doval. Among the string of acronyms that cumulatively make up ‘India in Nepal’ as we speak – PMO, MEA, RAW, IB, MHA, NSA – it is the last that seems to direct all, with ‘operational’ flair. The ongoing misuse of the ‘agencies’ against Kathmandu must be evaluated to help rescue Indian diplomacy for the sake of India’s self-worth and its aspirations to be a player of global note.

Comfortable government

Nepal’s political class has hardly covered itself with glory when it comes to confronting the southern viceroyalty. It seeks protection and personal favours from the Delhi ‘masters’, everything from education scholarships for relatives to funds to fight elections. The tendency is evident when Kathmandu’s politicos seek intimacy with the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) foreign department head Vijay Chauthaiwale for his presumed access to PM Modi – to the extent that Arzu Deuba, MP and spouse to former prime minister Deuba, thought it a great boost to put a rakhee on Chauthaiwale’s wrist.

Nepal’s politicians are certainly not above opportunism, to show a radical populist anti-India posture while out of government, being at New Delhi’s beck and call when in power. What has changed in the recent past is that much of the political spectrum has been compromised and brought ‘in line’ to suit New Delhi’s designs, and the strident anti-India sentiment is no longer heard at the very time that Indian control of Nepal’s political economy is galloping ahead.

In March 2021, while challenging the K.P. Oli government on a television programme, Dahal suggested that the Nepali ruling class must come up with a leadership combination that is ‘comfortable’ for New Delhi, i.e., excluding Oli’s Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) or CPN (UML) and including the Nepali Congress, the Madhesi parties and his own Maoist Centre. Dahal has clearly promised to toe the line on all that New Delhi wants from Kathmandu, and for the show of fealty he was rewarded a red-carpet reception at BJP party headquarters in New Delhi by party chief J.P. Nadda.

And today, Nepal has a ‘comfortable government’ as far as Raisina Hill is concerned. While till recent it was believed that India preferred ‘steadfast’ Deuba to fickle Dahal as prime minister, it seems to be willing to prop up the latter for his tremendous malleability.

When he became prime minister for the third time, the first interview Dahal gave in December 2022 was not to a national news organisation but to the Indian channel ABP. He declined an invitation from Beijing to address the Boao Forum, which he has attended in the past as prime minister, so as not to displease a mollified New Delhi. Dahal has confided to his closest circle of the excessive pressure he faced from the Indians to break his bond with the Oli and go with Deuba. The fall from the heights of a B.P. Koirala to the level P.K. Dahal lays bare Kathmandu’s eroded sense of self vis-à-vis New Delhi, a downfall that should interest and concern Southasia scholars everywhere.

Amidst the sea of weakling politicians in Kathmandu, the exception that stands out is the UML’s K.P. Oli, intemperate with his tongue, given to harangues, but more than willing to challenge New Delhi – so much so that the Indians have worked (successfully) to remove him from government and (unsuccessfuly) to push him into the political wilderness.

In office, Oli showed the gumption to stand up to the Indian blockade, and in later years was willing to challenge the Modi vision – from suggesting a Nepali site in Chitwan as the true Ram janmabhoomi, thereby setting one myth against another, to leading the constitutional amendment to the official Government of Nepal map incorporating the territory of the Limpiyadhura triangle as Nepal’s own. (The new rendition is termed the ‘pointy map’, or ‘chuchhe naksa’.)

As the bilateral relationship plummeted, Oli teased New Delhi for having abandoned the national motto of ‘Satyameva Jayate’ for ‘Singhameva Jayate’. No wonder Delhi Durbar is displeased, but the bravado does not attract applause in Kathmandu, where curiously the cognoscenti and media is arrayed against in Oli.

Dos and don’ts

These are dangerous times for Nepal, with BJP leaders viewing all domestic and external matters through the lens of winning the 2024 general elections. It behoves Kathmandu’s policy-makers to be alert to possible machinations to make Nepal serve the BJP agenda. Among other things, there will be efforts to export Hindutva rage in various forms, including the involvement of Nepali counterparts of the RSS and their shakhas; trigger a collapse of the secular constitution; raise once again the spectre of hill-plain divide; raise the China bogey to agitate the Indian populace; and so on.

For its part, India’s PMO must consider that only a government that has the trust of the electorate through the ballot — rather than forced coalitions — can negotiate on the Limpiyadhura border dispute (including the Lipu Lek pass and Kalapani enclave) that are obviously at the centre of its concerns. India has got it wrong if it believes that a manipulated government formation led by a compromised prime minister can deliver – talk of ‘afnai khutta ma bancharo’, the Nepali equivalent of shooting oneself in the foot.

Besides seeking to belittle Kathmandu at every turn, New Delhi must not project nor perceive the Madhesi population and leadership as fifth columnists, and desist from the extreme pressures it exerts on the political and civic leadership of the plains. While the Madhesi community is rightfully livid at the second-rank status it has had to suffer historically under the Kathmandu-centric state, the corollary is not that proud citizens would want to be perceived as some kind of NRIs. As Nepal consolidates under its new constitution, the Madhesi population will start seeing the firm possibilities of equal citizenship, while maintaining cultural and familial links across the international border.

India’s efforts to undo the ‘pointy map’ through coercion rather than negotiation cannot be expected to work. Neither should it try to force through a citizenship bill that would, among other things, favour Indian women marrying into Nepal with instant citizenship, without reciprocity in India’s own laws. This proposed provision was one of the elements India had wanted included directly in the new constitution.

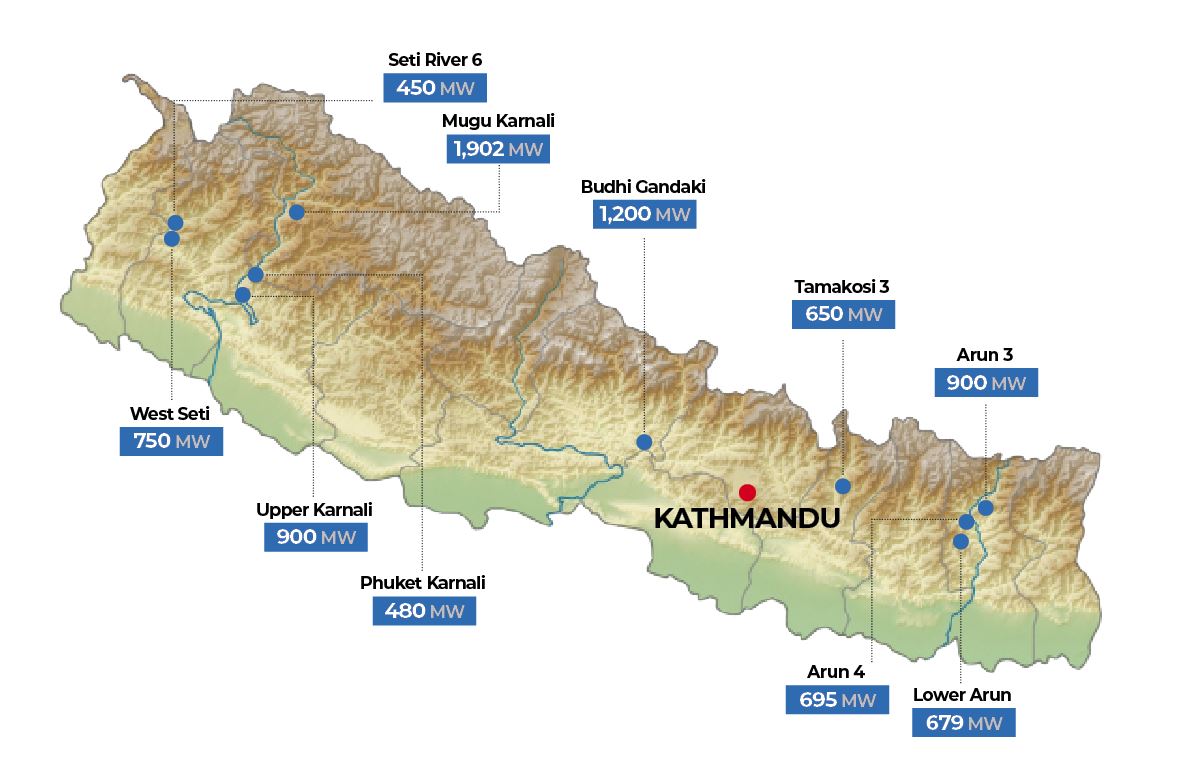

New Delhi should note the increasing unease in Kathmandu with its move to capture all large hydropower projects using the pliant Deuba-Dahal regime, which would impact Nepal’s geopolitical autonomy. As for India’s plans for huge reservoir projects on the Gandaki, Kosi and Karnali tributaries of the Ganga to feed its urban and agricultural demands and the harebrained ‘river linking’ scheme so favoured by Indian technocrats – beyond seeking Kathmandu’s acquiescence New Delhi should consider geology, seismicity, siltation, inundation and also fertility in the Ganga plains.

There are many urgent ‘don’ts’ to keep in mind on bilateral matters, but there is one extremely important ‘do’ – accepting and making public the report of the Eminent Persons Group on Nepal-India Relations (EPG). The Group was formed in January 2016 and made up of eight intellectuals and civic personages from the two countries, as selected by PM Narendra Modi and PM K.P. Oli in 2017. After many meetings, on July 2018, the group came to a consensus document to set Nepal-India relations on a course for the future, including on how to deal with the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship.

The agreement within the group was that the document would first be presented to the Indian prime minister, then to his Nepali counterpart. Incongruously, PM Modi’s office has stonewalled the entire EPG process for nearly half a decade now, referring through time to the prime minister’s ‘busy schedule’. Indeed, the New Delhi authorities seem to want to forget the entire matter, no botheration that this amounts to breach of good faith by one party with regard to a mutually agreed process. One senior MEA official even said that the EPG was a group of ‘independent individuals’, deliberately misleading the provenance of the Group from the highest levels in both countries.

In January 2022, former foreign minister and coordinator of the EPG from the Nepali side, Bhekh Bahadur Thapa, told the Nepal Live news portal: “How can they ignore the report which was born out of the commitment from none other than the Prime Minister of India? The sea change in the attitude toward the EPG from the Indian side is astonishing.” Another senior member of the Group and former ambassador to India, Nilamber Acharya, told the same portal last April: “The EPG report must be accepted by India. The world has changed. India has changed and Nepal has changed. We must rise above the mindset of colonial times.”

Rather than surrender to this show of absolutist power by India’s rulers, ideally, the seven members of the EPG (one member is deceased) must make a push for acceptance of their document by the Indian prime minister. Barring that, the Nepali members should unilaterally present the document to the Nepali prime minister, but even that may not happen given the subservience of PM Dahal before his Indian counterpart. The remaining option is for any one of the EPG members of either country to make the document available to the public – keeping in mind that it has the potential of rescuing bilateral relations for the long run. Each government would remain free to formally accept the EPG report in whole or part, or reject it likewise.

‘Chakari’ and ‘badhyata’

What does India want so much from Nepal that it seeks to create a client state with compromised leadership? The more Nepal’s democracy strikes root, the more New Delhi seems to feel the urgency to overpower. Constantly, there are attempts to infiltrate and impact the Nepali psyche, from bankrolling the start-up of an English daily of Kathmandu as ‘soft power projection’ to ensuring the growth of pliable think tanks that talk up New Delhi’s positions.

For its supposed geostrategic gains, New Delhi will only exploit the openings provided by Kathmandu. And here, extreme diffidence is at play, marked by the politicos who lack confidence in their country’s past history and future prospects, who flock to the wooded ambassadorial estate at Lainchaur for favours, and desperately seek audience with officials who fly over, from Kwatra to Chauthaiwale. The quintessentially Nepali word to describe the obeisance of these fawning Kathmandu leaders is chakari – to wait upon, show deference to the powerful.

This subservience is exemplified in the tragic case of Jai Singh Dhami, a citizen from the Darchula District who was disappeared on the Mahakali border river on July 30, 2021 when Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB, under ministry of home affairs) personnel severed the cable on which he was crossing over. The Kathmandu government, then led by PM Deuba, responded with resounding silence.

PM Deuba himself did not use his talks with PM Modi in Delhi in April 2022 to demand a glide slope over adjacent Indian territory for the just-inaugurated international airport to serve Lumbini. On the other hand, Deuba did Modi a favour by making a pilgrimage to Benaras, and being the first visiting head-of-government to walk the ‘Gangaji-Vishwanath vista’ that has so decisively transformed the ambience of the old city core.

Among the most egregious projects of the Indian apparatchiks was placing an ambitious and corrupt ex-bureaucrat, name Lokman Singh Karki, as head of Nepal’s anti-corruption agency, CIAA, in May 2013. The idea was to try and emulate Pakistan’s National Accountability Bureau (NAB and, increasingly, India’s own Central Bureau of Investigation, CBI) and use corruption charges to control independent-thinking politicians, bureaucrats and activists.

Kathmandu’s political class was overwhelmed by New Delhi’s pressures, and President Ram Baran Yadav succumbed and swore Karki to office, citing ‘badhyata’. Nepali leaders who capitulate to Indian pressure on any arena of activity tend to speak euphemistically of badhyata (forced acquiescence).

Nepal will be Nepal

It is not only the case that the poorest Nepalis go to toil in India – the poorest Indians come up to Nepal. The country’s east-west expanse lies astride the Ganga maidaan with its largest concentration of human poverty in the world, whose future cannot be imagined without concomitant economic growth north of the border.

Nepal it is which attracts the poorest job migrants from the south, from Purvanchal, West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand and Orissa, making Nepal the seventh largest remittance sender to India. Thus, one plea to India’s opinion-makers while demanding a pushback on Nepal adventurism would be to introspect on the growing human poverty in the Hindi heartland, and how this can only be addressed in part by Nepal’s stability and well-being. One can even extrapolate that New Delhi’s meddling in Nepal indicates its disdain for its own densely populated simanchal border regions.

Leave Nepal alone and you will find the country and people will revert to their instinctive affinity for India. After years of trying to influence Nepal and emerging red in the face, New Delhi should call off its operatives, and revert to a bilateral relationship that is managed diplomat-to-diplomat, politician-to-politician and people-to-people.

Indians should make peace with the fact that Nepal is a different country across the open border, one whose default position is camaraderie with India. Nepal can never be anti-Indian, it will be Nepal.

Kanak Mani Dixit is the publisher of Himal Khabarpatrika and the founding editor of Himal Southasian.