From The Kathmandu Post (16 January, 2015)

You will write the constitution if you understand the needs of conflict victims and the Tarai’s poor

Things are coming to a head in the Constituent Assembly (CA) only days before the January 22 deadline, as it is finally allowed to discuss substantive matters after being waylaid all this time in the Baburam Bhattarai committee. As the CA prepares to proceed amidst boycotts and threats of street action, keep in mind that the new constitution is meant for the people of this country. And among the people, the basic law is meant to favour the weakest and most marginalised.

The two categories which fit the description of weakest and most marginalised are the state-side and Maoist victims of conflict, and the largest marginalised communities of Nepal, viz the Dalit and Muslim of the Tarai plains. Is the constitution-writing addressing their needs and wants? Thus far, it has not, and mainly because the drafting has been hijacked by a cabal of elders who have not allowed transparent debate among representatives elected by the citizens in November 2013.

The process

At long last, the constitution writing has finally entered the ‘process’, which includes discussion of the draft provisions presented by the Nepali Congress (NC) and CPN-UML on the one hand, and the 30-party alliance including the UCPN (Maoist) and Madhesi Morcha on the other. The ever-present threat of the Maoist leadership sparking communal discord has held back the NC and UML thus far, despite their ability to muster a two-thirds majority.

The identity-related positioning of the Madhesi Morcha is more complex than the personalised agenda of Maoist leaders Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Bhattarai, added that most of the leaders of the Morcha espouse non-violent, democratic politics. But somehow, they have been made votaries of the plains-specific province idea and now, cannot let go. The present coalition government has not made it easier for them, continuing to function as if the entire identity movement (Janajati and Madhesi) had not happened, as seen in its continuing ‘bahun-first’ policy of appointments to public bodies.

But a constitution is about constructing the future while learning from the errors of the past that continue into the present. Here, the malevolent positioning of Dahal-Bhattarai is less relevant than the fears of the Madhesi fold (that the Pahadiya bahun will continue their hegemony over state institutions in the absence of plains-specific provinces). Rather than try to come up with a full-fledged constitution, the two largest parties in the CA would do well to come out with a draft text ready for discussion among the populace. In this writer’s opinion, this will promote participatory ownership of constitution writing and reduce societal tension and the sense of hopelessness.

Remember Nanda Prasad

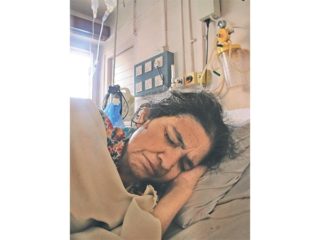

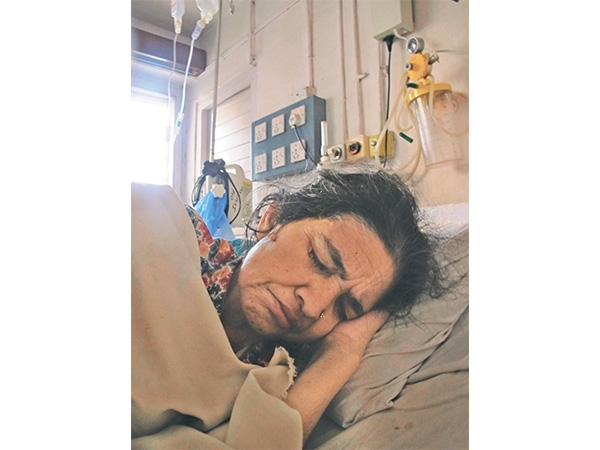

Gangamaya Adhikari lost her husband to hunger strike 117 days ago, while demanding justice on the Maoist murder of their son. The body of Nanda Prasad remains in the Teaching Hospital morgue, a tragically mute witness to the blackmailing of the ‘democratic’ forces by the Maoist leadership, whose key preoccupation is general amnesty for all perpetrators of atrocities (torture, rape, abduction, murder).

In the so-called transition period since 2006, the victims of both rebel and state excess have been abandoned by ‘democratic’ politicians intent on appeasing the Maoists. The only hope of justice for Gangamaya (and Purnimaya Lama, Devi Sunar, and thousands of other victims) rests in the promulgation of a democratic constitution. Such a constitution will revive rule of law in the land, including criminal accountability for war crimes. If the politicians dare to establish a perpetrator-friendly Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the days prior to promulgation, the victims and human rights community will have to fight to annul the institution and start anew.

Gangamaya has been on a fluid-only-fast at Bir Hospital since the death of Nanda Prasad. ‘Je suis Gangamaya’ (I am Gangamaya)—only if we identify with her commitment to justice as the highest value of humanitarian society will Nepal have the kind of constitution that the citizens deserve.

Tarai Dalit

The demand of the Madhesi Morcha for one or two plains-based province(s) would create roadblocks in the plains’ access to the natural resources of the highlands. The expression ‘khaipai ayeko’ says it all—no one wants to let go of largesse once tasted. You only have to observe how last month Sindhupalchok district extracted a pound of flesh in hydropower distribution, setting a precedent on exclusive localised privilege,

to understand how the hill-plain dynamic will unfold tomorrow under erroneously crafted federalism.

Let us hope these fears are unfounded, but the federalism as demanded by the Morcha looks like it will impoverish the plains people, given the high concentration of national poverty in the Tarai. And more than others, it will hit those who make up the marginalised of the plains—the Tarai Dalit, Muslim, and Tharu.

The understandable anger of the Madhesi elite against Kathmandu’s Pahadiya elite is being allowed to get in the way of writing a constitution that will give the people of plains origin political power and clout in future federal units, which would translate into economic wellbeing. This power would simultaneously support a stronger, proportional presence in national politics.

All in all, what a bizarre way to write a constitution, when the poorest citizenry in the largest numbers is being forced to silently watch as its future is being discussed in Kathmandu by insensitive leaders of all stripes.

The Interim Constitution

There are now limited options before the polity if constitution writing is to support the interests of Gangamaya Adhikari and the victims of conflict, and the Muslim, Dalit and Tharu of the plains. If the Maoists and Madhesi Morcha continue to stonewall discussion, the recourse should be to ‘fast track’ the production of a draft constitution and present it to the public for discussion on January 22. If it looks like there will be bedlam even in trying to do that, consider regularising the Interim Constitution.

The Interim Constitution is the document under which the country has run for last eight years, since January 2007, surviving and capable of addressing numerous

crises and vicissitudes. It has been accepted by the entire spectrum of political forces, from the revolution-minded Netra Bikram Chand to the Madhesi Morcha. It was this document which confirmed the republic, federalism, a mixed electoral system with proportional/direct elections, and which has sought to keep religion out of politics and governance.

The Interim Constitution can be regularised and adopted with very little adjustments, but must include a timeline for the definition of federal provinces through a commission, to present the results to the continuing Parliament (which has another three years to go). The only negative for the politicians would be the embarrassment of having wasted six years in constitution-writing, but since all are culpable, there will be no one to take the blame.

With or without a brand new constitution, or a document with ‘interim’ lopped off, we must move immediately to orgainse local elections this spring. And the country will have left behind the bad times if we can

find it within us the capacity to understand: first, what are the interests of the citizens most in distress; second, the nature of the comrade-commandants who have over nearly two decades worked to destroy the economy and polarise society—and are blocking the constitution in their bid to remain politically relevant.