From Himal Southasian, Volume 24, Number 5 (MAY 2011)

While studying law at the University of Delhi during the mid-1970s, I stayed at Jubilee Hall hostel, regarded as the larger but poorer cousin to Gywer Hall next door. But Jubilee had a special distinction that very few noticed, and it was not the peacocks that flew in to the back lawn from the nearby ridge. In fact, it was the Ridge of New Delhi itself that was so special about Jubilee Hall, because it provided a feeling of being nestled amidst the geography of the entire Subcontinent. That seemed important for me – although my hostel-mates had other preoccupations, such as preparing for the IAS examinations in order to get into the Indian civil services while enrolled in Delhi University, making as if studying for their law, economics or sociology degrees.

The Aravalli Range starts in Gujarat and travels through Rajasthan, skirting across the northern tip of Old Delhi to end exactly here, at this point, outside the veranda of Jubilee Hall. The River Jamuna, which comes down from the Himalaya, hits the Ridge and curves away at this point, unable to go further south because of the rocky outcrop. From here it goes eastward to join the Ganga, Ghagra (Karnali), Gandak, Kosi and Brahmaputra, to submit finally to the Bay of Bengal. For those living in the plains – and Delhi is more or less part of the plains – the ridge and its link to the riverine geography of the Ganga maidaan connect you across the expanse of the Subcontinent to the delta. It certainly made me feel connected, though not everyone seems to feel the need for location for like I do.

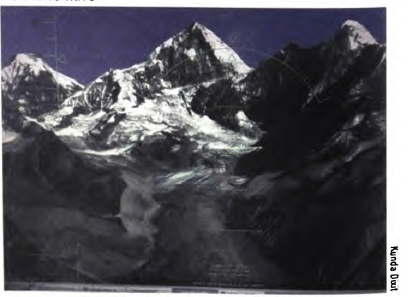

All of this explains part of why Kathmandu is such a fine place to live. If you are in Lucknow, there really is no notable geographical feature by to place you where you are. The Gomti is not all that great a signifier. At least Patna and Benaras have the mighty Ganga. Gorakhpur has nothing at all, not even a Gomti. Whereas Kathmandu…! There is the first ring of hills – Phulchowki, Nagarjun, Chandragiri and Shivapuri, each with its distinctive profile, mythology and angle of attack. To the south, past the airy emptiness of the last ridgeline, you can imagine the Ganga plain, 40 miles away; while to the north, past Phulchowki, is the sub-Himalayan 16,000 ft range of the Gosainkunda Lekh. Beyond lie the Himalayan ramparts, visible in a 350 km swathe all the way from Sagarmatha/Chomolongma/Everest to the Annapurnas in the west.

When an aircraft takes off from the aerodrome in Kathmandu, given the lay of the land, it has to circle and come overhead, allowing enough time for an observer on the ground to check whether it is a Thai or Qatar Airways, Etihad, Jet, Spice, Nepal, PIA, Biman or Kingfisher plane. In this valley, there are none of the anonymous takeoffs from the airfields in the plains. It is not just that this place is not flat, though that helps. You can see how the unplanned urbanisation creeps up the hills and across dales, and in the monsoon, you can watch clouds from the adjacent valleys stealthily invading Kathmandu. Spring is a time of storm, and the thunderclouds all brew in the southwest, beyond Chandragiri, and come sweeping over us.

Till recently, therefore, I have at times felt a bit sad for the people of the plains, who live with seemingly few geographical reference points – no parallax at all that excites the eye with the change of positioning with regards to a mountain or hillock. How dreary it must be to have nothing to appreciate but the orange globe of a setting sun and the returning cattle raising dust in that godhuli hour.

Till recently, I said. Because even if you are stuck in an endless plain, you can now call up Google Earth and take a look at your surroundings – the nearest river’s meander, the highway, railway station or factory complex. You can come as close as to see your own courtyard, though a bit fuzzy, or pull back to contextualise yourself with the Himalaya, hundreds of kilometres to the north.

I am not sure, however, whether all of this access to digital faux geography is a happy evolution. Sitting at the Himal office terrace in Patan Dhoka, looking to the north, you see the chain of Jugal Himal. This region was first explored (by an Occidental, that is) during the 1950s, by the laconic, self-deprecating essayist H W Tilman, after whom the Tilman Col in the Jugal Himal is named. He writes about the endless difficulty of reconnoitring in this area.

But today, you do not even have to go on a mountain flight – the Nepali innovation that takes off from Kathmandu, destination Kathmandu after a spin to the Everest region. Google Earth now gives you not just a topographic image, it provides realistic terrain of the individual mountains – Dorje Lhakpa, Phurbi Ghyachu, Lonpo Gang, Dome Blank – and you can fly your flight simulator aircraft close to cols and cliff-sides, cross over to Tibet and explore the glacial lakes, come back onto the Nepal side to investigate the glaciers and seracs that you have always gazed at from faraway Kathmandu.

Perhaps it is not good to have all these possibilities, helping you do away with your eye and your feet, to be supplanted with digital exploration. In the end, better perhaps to live in the flats and watch the sun go down all orange, which is much more real – it locates a real star, a real horizon, real haze, real cows, real dust.