From Himal Southasian, Volume 22, Number 3 (MAR 2009)

The ten-hour-long luxury-Mercedes-Benz bus ride to Cox’s Bazar across the flat expanse of Bangladesh ends with a surprise. Coming up on Chittagong, the vehicle encounters an incline. For a country that rises northwards at a rate of just about five centimetres over a hundred kilometres, that is quite an achievement. And before long, you see what looks like a hill in the distance, though it could be a cloud bank. No, indeed it is a hill – a little bit off the Arakan range, which sneaks into Bangladesh to make this country one that also contains slopes and rocks, in addition to soil, rivers and mangroves. And, of course, beaches.

We were heading down to Cox’s Bazar to take part in a meeting of Southasian journalists. There were unbelievers amongst us, which included journalists who swore by the beaches of Karachi, Colombo and/or Goa. The landlocked Nepalis kept their own counsel on this matter, as did the sizeable delegation from Afghanistan.

But indeed, Bangladesh did have a beach, claimed, at 124 untrammelled kilometres, to be the longest in the world. Correct that: the longest ‘undivided’ beach in the world, as a qualifier to take on challengers from Brazil to Australia to California, spoilsports who would like to take this natural wonder from out the grasp of Bangladesh. Also, the brochure claim for Cox’s contains the rider that the beach includes “mud flats”. Oh well.

The town, we are told, was named for a colonial officer in the time of Warren Hastings, who came here, did some good, and then died. And so, just as Chomolongma, as the highest peak, carries the name of the Director-General of the Great Indian Trigonometrical Survey, Sir George Everest, who never laid eyes on the massif, so too is the longest beach now known by the name of Lieutenant Hiriam Cox.

Cox’s Bazar is described in one brochure as the “epicenter of Bangladesh’s tourism, and the favored staging ground for visitors heading out to the pristine white sand beaches and balmy, shark-free waters”. Shark-free I will concede, because we did not see anyone being dragged away against his will. And there were, of course, enough Bangladeshi tourists about – men wading into the water with rolled-up trousers, ladies in sarees, salwars and jewellery. The crowded shore is about the most sedate anywhere in the world, and not a patch of skin to be seen. That is probably the tourist attraction here at Cox’s: an absolutely unique phenomenon of full-dressed masses attending to the call of the ocean.

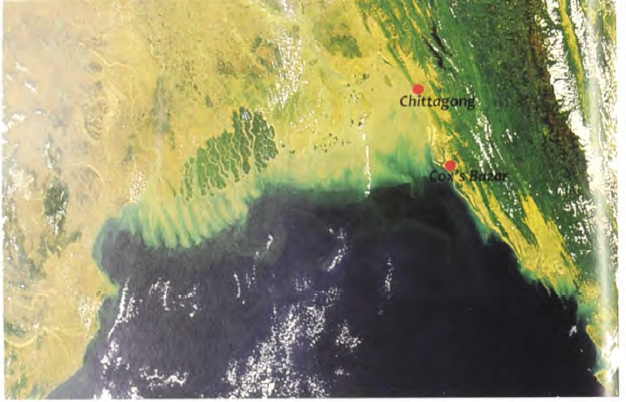

Alas, for all the claims made for the beach – the surf, the sand, the length – it has to be said that the chances of attracting sun ‘n’ sand frolickers away from Hikkaduwa or Goa are slim. The reason is encapsulated in the term ‘mud’. No, this is not pollution, just healthy silt. The beach of Cox’s Bazar lies astride and a little to the south of the delta where the Ganga and Brahmaputra (Jamuna) debouche unto the sea, through the many-tentacled delta. Thus, some of the highest volumes of silt carried by any watercourse on earth empty next door to the beach.

I have nothing against silt. In fact, I place it in high regard, for having created, over the eons, what we know today as Bangladesh, and for providing the land with significant fertility to boot. But I do find it distressing that the silt impacts on the quality of the beach experience at Cox’s Bazar, as I presume it does along the entire stretch of 124 km.

One ends by expressing the hope that one is completely misplaced in the conjucture, which could be titled as a paper, “Silt and the long-term considerations of beach tourism in Bangladesh”, and submitted to the Southasian Journal of Tourism and Geomorphology. Till such time that the matter of silt at Cox’s remains a secret, however, it is suggested that the National Tourism Authority in Bangladesh sell the stretch as: “The longest, undivided, fully-clothed, shark-free beach in the world, as near as we are able to make out…”