From HIMAL, Volume 6, Issue 2 (MAR/APR 1993)

Is there today in South Asia a movement to establish a “Greater Nepal”? If not, is such a movement likely to arise anytime soon?

Most connosieurs of South Asian news and politics claim not to believe that there is a movement afoot to create a “Greater Nepal” along the Himalayan rim-land of South Asia. Like Jyoti Basu, the Chief Minister of West Bengal, they maintain that the concept is a “bogey” pushed opportunistically by a handful of regional actors.

But there are some diplomatic and media circles in the Indian capital of New Delhi, who profess to lake seriously the idea of a Greater Nepal “conspiracy” or “gameplan”. Whether anyone believes it or not, therefore, “Greater Nepal” becomes an issue of geopolitical significance.

Those who have given Greater Nepal a high media profile over the last two years, apparently acting independently of each other, are Dawa Tshering, Foreign Minister of Bhutan, and Subhas Ghising, Chairman of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council.

Ghising has had ongoing spats with West Bengal´s Left Front government and Sikkim´s Chief Minister Nar Bahadur Bhandari. His method of confronting these challenges has been to raise a scare with issues relating to territory, language and nationalism. Over the last couple of years, Ghising has claimed that: Darjeeling is a no-man´s-land due to lacunae in the 1950 Indo-Nepal Friendship Treaty; that Kalimpong is leased territory actually belonging to Bhutan; that ´Gorkhali´ rather than Nepali should have been the officially recognised language in India; and that there exists a conspiracy for Greater Nepal.

In a 26 July 1991 letter to the Prime Minister of India, Ghising asserted that the recognition of ´Nepali´ rather than ´Gorkhali´ helped stabilise the Greater Nepal movement, which was a communist plot clandestinely supported by Indian leftists and Bhandari. The Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist Leninist), Nepal´s powerful opposition in Parliament, Ghising warned, was demanding the return of Nepali territories ceded to the British.

“That is why I am spending sleepless nights,” Ghising confessed to The Statesman of Calcutta. “My sixth sense and political acumen have repeatedly alerted me of the grave danger that the manifestations of the Greater Nepal movement .pose to the Indian Union. Surprisingly, this danger is completely unknown to the rulers in Delhi and Calcutta…”

The Foreign Minister of Bhutan finds common cause with Ghising. In January 1992, Dawa Tshering told a visiting Amnesty International delegation that Nepali-speaking southern Bhutanese rebels were “supported by groups and individuals in India and Nepal who support the concept of a greater Nepal, which is based on the premise that the Himalayas are die natural home of the Nepalese, a myth which is not supported by historical fact.”

The concept had attracted Nepali politicians in India and Nepal because “the green hills of Bhutan have become a paradise for the land-hungry and job-hungry poor, illiterate Nepali peasants from across the border.”

In Autumn 1992, as reported by the Kuensel weekly of Thimphu, the Foreign Minister informed the Tshongdu (National Assembly) that the political parties and people of Nepal were supporting the “anti-nationals” of southern Bhutan not merely because of ethnic affinity, “but more out of their deep-seated desire to promote the concept of a Greater Nepal”. The plan envisaged “Nepalese domination over the entire Himalayas by bringing Bhutan, parts of the Duars in West Bengal and Assam and the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland under Nepalese control just as in the case of Sikkim and Darjeeling.”

A Historical Yearning

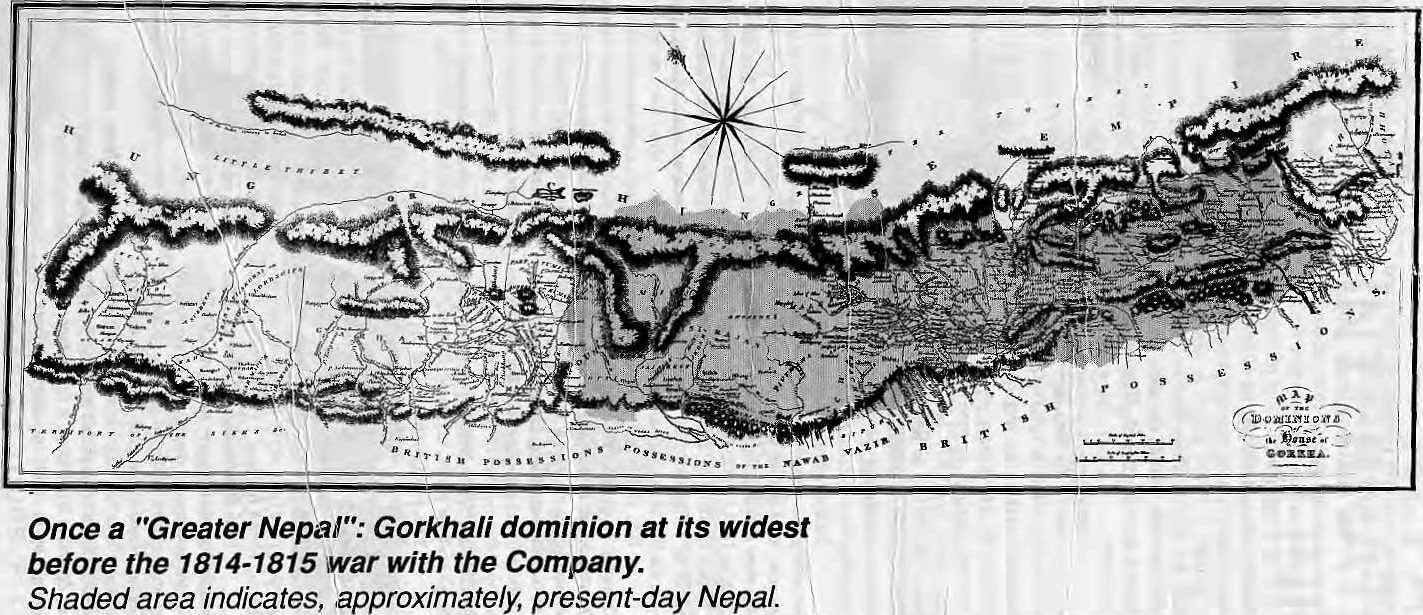

Of course, there was once a Greater Nepal — an historical Greater Nepal — but it did not last for long.

Until the mid-1700s, the principalities of the Central Himalayan region had been content at fighting each other for strategic advantage. But then, emerging from the mini-state of Gorkha, Prithvi Narayan Shah devised a method of mountain warfare, conquest and consolidation which extended his domain far beyond what earlier rajas had ever contemplated.

Within four decades, Prithvi Narayan and his immediate successors had incorporated the prize of Kathmandu Valley and pushed the Gorkhali frontiers from the Kirat regions eastwards to beyond the Karnali principalities of the west. The Gorkhali empire-builders then lunged westwards across the Mahakaliriverinto Kumaon, taking it in 1790. Garhwal was conquered in 1804, and other cis-Sutlej principalities were taken until the Gorkhali forces were laying siege to the fort of Kangra. Beyond, and probably within reach, lay Kashmir.

In 1813, this historical Greater Nepal extended from the Sutlej to the Teesta, spanning 1500 kilometres. Rule over this expanse was brief, however, and the 1814-1815 war with the East India Company saw the Gorkhali realm whittled down considerably. The real-time Gorkhali presence in Garhwal was for a little over a decade; Kumaon for 25 years; and Sikkim for 33 years. The Treaty of Sugauli, between a chastened Gorkhali state and the Company, was ratified in 1816. It stripped Kathmandu´s rulers of about 105,000 sq km of territory and left Nepal as she is today: a country of 142,000 sq km that has not shown extra-territorial ambitions since.

Even as the historical Greater Nepal went into eclipse, there began a process of migration out of the Central Himalaya which would lead to demographic conflicts more than a century later. During what one historian has characterised as the “silent years” of 19th century Nepal, the pressures of the State on the ethnic and other hill communities increased dramatically. Political repression, economic exploitation and, possibly, over-population, pushed peasants eastwards along hill and Duar towards the Indian Northeast, where the British needed Nepali brawn to harvest timber and to open up territories for settlement and tea gardens. Over the decades and well into the 1900s, Nepalis became heavily concentrated in the lower hills of Sikkim, Bhutan and in the Duars. In lesser numbers, they extended themselves right across the Northeast and as far as today´s Myanmar.

Would this scattered community of Nepali labour/peasantry ever come together to form a Greater Nepal?

The Likely Conspirators

Under present circumstances, a Greater Nepal could emerge from one of three directions: the Nepali State, the Sikkimese state, or the Lhotshampa Nepali-speakers of southern Bhutan.

The Nepali State. After historical Greater Nepal was truncated by the Treaty of Sugauli, Nepal entered an insular era which lasted till 1951. Much of this period was under the Rana oligarchs, who understood well that they were not to eye the neighbouring territories of the Raj.

With the overthrow of the Ranas, Kathmandu´s middle class shook off its century-old political shackles and was swept away by an upwelling of dated Gorkhali sentimentality. Childhood textbooks harked back to the halcyon days of expansion, and patriotic songs extolled the Gorkhali prowess. However, while there was a yearning for a glorious past, there was no militancy.

One folk lyric, collected in the early 1950s by Dharma Raj Thapa, went like this:

What has happened to us Nepalis?

Our own songs have all been lost.

We did twice best the Germans in battle.

We did take the Sutlej and Kangra.

But today out own voice is heard no more.

A pan-Nepali movement did not emerge because Nepalis realised that the new Indian rulers had merely supplanted the British Viceroy.

If Nepali politicians gave up the thought of incorporating Kangra and Darjeeling, it was not necessarily because they did not relish the prospect. It was more the impracticability of establishing a Greater Nepal on India´s front lawn. A Greater Nepal would have to include the takeover of Sikkim (now a state of the Indian Union) and Bhutan (which falls squarely under New Delhi´s security umbrella). Which government of Nepal, whether Nepali Congress or any Left combine, would be willing to take such a dare? As one diplomat in Kathmandu asked rhetorically, “Would not any Greater Nepal move by Kathmandu bring it up against a certain institution called the Indian Army?”

The three decades of the autocratic Panchayat system might have provided leisurely occasions to push for a “Brihat Nepal”, to be spearheaded by the King, a direct descendant of “Badamaharaj” Prithvi Narayan. However, the defining foreign p o I icy demarche during King Birendra´s years as unfettered monarch was actually the Zone of Peace proposal which, far from being pan-Nepali in nature, was seen by some as an attempt by Nepal LO protect itself from a “Greater India”.

With the second coming of democracy in the spring of 1990, the freedom to speak out has once again provided a fillip to those few who continue to be obsessed with re-establishing the Gorkhali state´s lost land and glory.

A group calling itself the Greater Nepal Committee was formed in Kathmandu in July 1991. It sent a letter to some Kathmandu embassies, stating, “Since the Nepali people are now sovereign, it is but natural that they worry about their nation and the perpetual security of its territorial integrity.” Under the 1950 Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship, India should restore unconditionally to Nepal the territories east of the Mechi river and west of Mahakali. The Committee´s objective was “to create a world-wide public opinion in favour of the ´Greater Nepal´ and to achieve it.”

The letter was signed by Surendra Dhakal as member of the Committee. Dhakal, till recently, was the editor of a two-year-old Kathmandu weekly, Rangamanch. Dhakal says that by campaigning for Greater Nepal, he was fulfilling his moral and nationalistic duty. But why is it that he seems to be crying in the wilderness? He replies, “Right across the political spectrum, Nepali leaders are cowed down by fear of India, which is why they were unwilling to speak out In support.” Dhakal said he did not know of any organization other than his own that was pushing for a Greater Nepal.

Whatever might be the seriousness with which some individuals and groups regard Greater Nepal, their enthusiasm might be dampened somewhat when they look within the nation-state of Nepal. Since the spring of 1990, there has been a surge of ethnic and regional assertion within Nepali boundaries. At a time when the Nepali State is looking inwards to resolve these challenges, it would hardly seek external adventures that would directly challenge the Indian State.

While Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala told Sikkimese journalists in Jhapa that the Greater Nepal idea is “a product of unstable minds”, Nepal´s mainstream Left seems to be just a bit ambivalent towards Greater Nepal — they like the concept but are unwilling to do anything about it.

As much is clear from the Rangamanch´s interview with Madan Bhandari, General Secretary of the CPN (UML). He said, “I do not want to make any political comment on Greater Nepal. But as far as it is a question of feeling, as a Nepali I can express the emotion that Nepali-speakers who are linked through their ancestry should be able to come together as one united family. If the Greater Nepal issue progresses ahead, then in a peaceful manner, taking into account the sentiments of alt people, this thing can be decided.”

Asked about current CPN (UML) policy on the matter, however, Ishwor Pokharel, Central Committee member of the CPN (UML), was unequivocal: “We have made no formal statements on the question of Greater Nepal and no leader of the party has endorsed this concept. We have decried unequal treaties between Nepal and India, but that is in the context of the 1947 Tripartite Agreement and subsequent treaties. We have not gone back to question the Sugauli Treaty of 1816, nor asked (or cession of land to Nepal. The party regards the Greater Nepal proposals as neither relevant nor timely and we have not taken them seriously.”

The Sikkimese state. Today´s Sikkim is dominated by Nepali-speakers and the Bhutia/Lepchas who were here first have been marginalised. Chief Minister Bhandari has ruled Sikkim for 12 years and emerged as the most powerful voice of Indians of Nepali-origin. A charismatic and ambitious man, Bhandari must seek successes beyond his small state. Could a move for Greater Nepal come from him?

Under present circumstances, it is not realistic for Bhandari or any other Nepali leader in India to have visions of becoming a leader of Nepali-speakers of South Asia as a whole. “Greater Sikkim”, however, seems a more likely possibility. In a July 1991 press conference, as reported by the Sikkim Observer, Bhandari himself did indicate a preference for a Sikkim with Darjeeling incorporated into it.

Sikkim´s historical claims over the Darjeeling hills would not make untenable the demand for a united state. (The Darjeeling hills were gifted by the Chogyal to the British as late as 1835.) But the establishment of such a Nepali-speaking enlarged state within India would be complicated as ii would impinge upon the turf of Ghising and West Bengal.

B.S. Das, a former Indian envoy to Thimphu, is of the view that if Bhandari´s emergence as a spokesman for all the Nepalis settled in India remains within bounds, it does not become a problem. However, he writes, “if these forces are allowed to become stronger by Indian neglect or Bhutanese mistakes, the concept of Maha Nepal will emerge under the garb of the so-called Greater Sikkim.”

The Lhotshampa. The third category of possible conspirators would be the Lhotshampa of Bhutan, in particular the 85,000-plus refugees who today populate the camps of southeast Nepal. However, it appears that the Lhotshampa’s most logical agenda would be to strive for greater power-sharing within Bhutan.

Says R.B. Basnet, President of the Bhutan National Democratic Party (BNDP), “There has been no document and no speech by any refugee leader which has spoken of Greater Nepal as our goal. This is something we have heard of only since we have come outside. It is a concept that is neither feasible nor desirable for Bhutan. It might have been brought up to create misunderstandings between Nepal and India and to undercut any Nepali support for the refugees.”

Since the Thimphu Government seems firm on not wanting the refugees back, there is only one party that can ensure the refugees´ repatriation to their homesteads — the Government in New Delhi. And the one move that would guarantee immediate antagonism from that quarter is for the refugees to agitate for a Greater Nepal. The refugee leaders perhaps realise this better than others.

Until the Lhotshampas emerged as refugees, there seems to have been very little political links between them and the Nepalis of Nepal. If there is any place where there is a feeling for being ´Nepali´ today, however, itis in the refugee camps of Jhapa. Said one camp resident, “This feeling arises because the very reason we have been made refugees is because we speak Nepali. I used to feel Bhutanese first and Nepali second. Now it is the other way around.”

Their refugee status, thus, seems to have forced the Lhotshampas to feel more ´Nepali´ than before. By creating the conditions that have made Nepali-speakers into refugees on a mass scale, therefore, the Bhutanese Government might have unleashed a process of self-identification that could become uncontrollable. For the moment, however, this seems unlikely, and the refugee leadership seems little inclined to initiate or join a movement for a Greater Nepal.

Eyes on New Delhi

It is clear that “Greater Nepal” is used by both Thimphu and Darjeeling as a weapon in their separate battles. It is a means to make the powerful politicians and bureaucrats in New Delhi sit up and take notice. But why is “Greater Nepal” such a convenient issue to catch New Delhi´s attention?

Both Ghising and Tshering know well the sensitivity of India´s strategists to-wards the “northern frontier”. They under-stand that New Delhi would not take kindly to the emergence of a Nepali-speaking super-state in such a strategic region, most particularly the Northeast.

Greater Nepal, at its geographical widest, would command the Himalayan rimland, controlling water resources, irrigation, hydropower, tourism, and trade with Tibet. Added if such a state were to be foreign, under Kathmandu´s rule, this would give rise to attendant geopolitical complications that New Delhi could well do without.

Among New Delhi strategists, therefore, a Greater Nepal state would be something to avoid. At the same time, astute diplomacy could make effective use of the Greater Nepal scenario, even if it were not entirely believable, as a means to keep the Nepali Government forever on the defensive. Stoking the Greater Nepal embers every now and then could serve a purpose.

What genuine concern there is in the plains about Greater Nepal probably refers back to the lurking fear that the martial Gorkhalis will one day arise and take over chunks of the Indian territory. This fear of the khukuri as a regional threat is quite dated to those who keep up with Nepali society. But many, some plains academics among them, continue to regard the “Gorkhas” as comprising of one unified race with the ability to articulate a political agenda and achieve complicated geopolitical designs.

Journalist Sunanda K. Datta-Ray wrote recently in The International Herald Tribune that the Indian Government “has long been wary of the Nepalis”. The claim for official recognition of the Nepali language is seen “as the thin end of a wedge of political demands by a martial race entrenched in pockets along India´s 1,500 mile Himalayan border…”

Tanka Subba, a sociologist and researcher at the North Eastern Hill University in Shillong, says that there is also fear of Nepali expansion from the tens of thousands of demobilised and retired Gurkha soldiers. “With so much military experience, so the argument goes, it may be possible for Nepalis to take over areas where they dominate.”

With the layers of worries and suspicion about the Nepali-speaking hills (sensitive northern frontier, a possible super-state, a supposedly homogeneous population, the martial legacy), a suggestion that the Nepal´s Left parties are planning a Greater Nepal putsch, or that Nar Bahadur Bhandari´s popularity among Nepali-speakers of India shows the way to Greater Nepal, or a suggestion that Lhotshampas of Bhutan are the vanguards of a Greater Nepal campaign — all serve Ghising´s and Tshering´s purpose to get New Delhi to see things their way.

When Jyoti Basu was dismissive of the Greater Nepal issue, one Sunday Mail reporter responded in a column, “…there is more to the ´Greater Nepal´ issue than meets the eye… Jyoti Basu may dismiss the allegation of a ´Greater Nepal´ movement as a ´bogey´ for political reasons, but the responsibility of the Union government goes deeper than that.”

The Nepali Psyche

Anirudha Gupta, political scientist at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, speaking on Greater Nepal, says, “There is no conspiracy, but there is an aspiration. Today, there is revival everywhere, and the Nepali-speaking middle class perhaps is no exception. Historical revivalism always brings up irredentist eruptions. In the Nepali case, people may start looking back to Sugauli and the ceded territories. The middleclass intellectual aspirations have always been an easy ground to revive a feeling of past perceived wrongs. When ´we´ and ´they´ comes to the fore of discourse, history comes alive, to influence me future.”

Under what conditions would a pan-Nepali ´ethnogenesis´ come about, which could then be expected to lead to a potent Greater Nepal movement?

There has been no wrenching incident in Nepali history, no trial by fire, that has led to the evolution of a collective national psyche. What has served to loosely bring the population together has been the force of Gorkhali expansion, the Kathmandu-based monarchy, a sense of being separate from the plains, and, most significantly, the spread of the Nepali language.

While a sense of identity is there, nationalism never settled deep. Prithvi Narayan Shah, unifier of Nepal, is not the icon of choice among the Nepali-speakers outside Nepal. Even Nepalis of Nepal do not make pilgrimages to spots of erstwhile military martydom, such as the battlefields of Nalapani and Malaun. Instead, except in Ghising´s present-day Darjeeling, the accepted symbol of pan-Nepali cultural identity is Bhanu Bhakta Acharya, the adi kabi of Nepali literature.

And the Nepali language is travelling along the hills. The economics of modern mass communications demands a dominant language, and along the central Himalayan rimland, Nepali has slipped into that role. Nepali is ascendant even as there is an unfortunate loss of ethnic languages and cultures right across the Himalaya. In order to reach the largest audience, politicians, journalists, advertisers, filmmakers; entertainers, educators, tradespeople and others are making increasing use of Nepali.

While it is language that binds the Nepali-speakers of South Asia, it is a weak thread. The feeling of ´Nepaliness´ in the Nepali ´diaspora´ is culturally charged, but not politically so.

One explanation for this weak politicisation might be that, barring Sikkim, Darjeeling and the Duars, the concentration of Nepalis in India is relatively low. Another could be that Nepalis do not form an ethnicity or race. For a Bengali or Marathi, it is a quick step from language to cultural identification. For good percentage of Nepalis, however, the Nepali language is a second language. There is so much that sets apart even Nepali-speakers from one another — tribe, caste, class, language, region, and so on. Political mass articulation is therefore harder to achieve among Nepali-speakers than it would be for a more homogeneous population.

A serious move towards Greater Nepal would have to have its origins in the targeting and humiliation of Nepali-speakers from all over, in an extreme scale, for being Nepali-speakers. Even then, the threshold of tolerance seems to be notched high for Nepali-speakers, both in and outside the mother country. Severe suffering inflicted upon Nepali-speakers over the last decades did not lead to a circling of wagons and die subsequent rise of region wide nationalism.

Neither the eviction of Nepali-speakers from Burma in the 1960s, nor the expulsion of Nepali-speakers from Meghalaya in 1985-1986 resulted in organised pan-Nepali reaction. When border points were closed during the height of the Nepal-India trade and transit crisis of 1989-1990, sentiments were affected among Nepali-speakers of India, but there was no political surge. And today, even with the volume of media attention that has finally focused on the Lhotshampa refugees, there is no political coming together of the larger Nepali-speaking world.

An Indian national daily recently presented with alarm the geographical extent of the Greater Nepal that is planned — it is to include large parts of Himachal Pradesh, Kumaon and Garhwal, Dehradun, all of Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and the Duars. The map presented by Dhakal of the Greater Nepal Committee covers more or less the same ground.

But a look at the rimland, from east to west, shows: a well-entrenched state of Himachal; the Uttarakhand region which does want autonomy, but only from Lucknow; a Nepal whose political leaders remain preoccupied with myopic politics of the short-term; a Darjeeling dial wants emancipation, but only from Calcutta; a Sikkim that wants Darjeeling, if it could have it; and a Bhutan that is every day shedding more of its Nepali identity.

The vested interests, the administration and the politics of the region are all well-entrenched, and only a Subcontinental wrenching that goes far beyond the Himalayan region would dislocate them and lead to, among other things, a Greater Nepal. While a large portion of the population of the region is able to appreciate the cultural attributes of the Nepaliness, the feel does not go deep enough to emerge as a movement for Greater Nepal anytime soon.

This article is adapted from a paper presented at a conference on Bhutan organised by the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 22-23 March 1993.