From Nepali Times, ISSUE #154 (18 JULY 2003 – 24 JULY 2003)

A Tribhuban University scholar delves into the papers of a British Resident and finds a treasure trove of Nepali history.

In his cubicle number 39 in the grand new edifice of the British Library, which houses all the papers of the erstwhile India Office Collection, Tribhuban University academic Ramesh K Dhungel is engaged in a scholarly exercise of a lifetime.

For the next three years, he will be sifting through the archives on Nepal left behind by Brian Houghton Hodgson, British resident to the Court of Nepal. In the process of cataloguing and cross-referencing, he has privileged first hand access to largely unearthed and little understood material which will help us enrich, and in some cases, rewrite the history of Nepal.

Hodgson came as a diplomat to a turmoil-ridden Kathmandu court as representative of the East India Company, and played his part in the intrigue and skulduggery between a mad king, an ambitious queen regent, the Pandes, the Thapas and the Bahuns. But he also evolved as a geographer, pioneering ethnographer, linguist, student of Himalayan Buddhism and naturalist with special flair for ornithology. Said one author, “Hodgson enriched museums, enlarged boundaries of more than one science.while upholding British diplomacy in a hostile military state.”

Hodgson was a ‘rennaissance man’. Born in Cheshire in 1800, he came from an English household visited by hard times, attended a school (Haileybury) established by the Company for educating administrators for the dominion. There, he came under the wings of Thomas Malthus, and even boarded in the house of that great pioneer of the study of political economy (besides population). In later life, he was also a champion of ‘vernacular education’ in India and was a challenger of Macaulay as well as the Orientalists who, respectively, pushed for English or Sanskrit.

Pride and poverty

So, it was to the long-term benefit of Nepal that this chronicler, archivist and multidisciplinary scholar was assigned to Himalayan climes to recuperate from the ‘fevers’ that would surely have killed him in the plains. After serving some time in Kumaon trying to undo the ravages of the imperial Gorkhalis, Hodgson first came to Nepal in 1820, was Assistant Resident 1825-33, and Resident from 1833-43. This was the cut-throat era during and following reign of strongman Bhimsen Thapa, just before the massacre at the Kot.

Of Hodgson’s personal life in Kathmandu, little is known other than that he lived a recluse with his books for company and some local scholars who came calling. But at some point he married a Nepali Muslim woman named Mehrussin, who he must have left when he departed Kathmandu, retired to England and then to Darjeeling (1845-1858), where he married an Englishwoman.

Of Hodgson’s personal life in Kathmandu, little is known other than that he lived a recluse with his books for company and some local scholars who came calling. But at some point he married a Nepali Muslim woman named Mehrussin, who he must have left when he departed Kathmandu, retired to England and then to Darjeeling (1845-1858), where he married an Englishwoman.

Assigned to a court marked by, in his own words, “pride and poverty”, Hodgson’s carefully gathered collections in just about everything related to Nepali life in the 19th century, from military intelligence to study of Buddhist iconography. These, as well as his extensive notes, were deposited in various libraries in Calcutta, Paris, London and Oxford. When these archives are delved into and fully understood, Nepali history will receive the depth and breadth for a discipline that till now has been too closely linked to the chronicles of kingly successions and national “bahaduri”.

While the personal papers and the Buddhism-related documents are kept elsewhere, Hodgson gifted all his papers on Nepal-specific diplomacy and statecraft to the India Office Collection. These are the papers that Ramesh Dhungel is now studying, in a project made possible by the efforts of Nepal scholars Michael Hutt and David Gellner and the head of the Asia-Pacific and Africa collection of the British Library, Graham W Shaw. Dhungel himself is a cultural historian with particular interest in Mustang,Tibet and Bhutan, and the Hodgson Manuscripts Project is funded by the London-based Liverhulme Foundation.

“Hodgson’s interest was endless and his research was endless,” says Dhungel. “Unlay kati doko, kati doko kagajaat jamma parey, kay bhannu. These papers are an encyclopedic record of 19th century Nepal. He collected anything and everything, from inscriptions to family histories and religious texts. Sometimes he bought them outright, at other times he had them copied at his own expense.”

Hodgson befriended pandits and gubhajus of Kathmandu Valley (in particular the great Patan scholar Amritananda, who became a valued informant), who were impressed by his knowledge of Sanskrit and Farsi as well as his ascetic lifestyle devoted to learning. Dhungel believes Hodgson revived the interest of Kathmandu’s powerful in their family histories, or bamshabalis, and received copies from many chautaria families, and even King Rajendra Bikram.

Two of the most detailed aspects of Hodgson’s work were on Nepal\’s judicial system commerce. He also studied the military strength of the army, and is considered an architect of the Gurkha induction into the British Indian Army. Hodgson is also credited, while already in retirement in Darjeeling, with having convinced a reluctant viceroy to allow an eager Jang Bahadur to participate in the quelling of the Sepoy Mutiny 1857-58.

Two of the most detailed aspects of Hodgson’s work were on Nepal\’s judicial system commerce. He also studied the military strength of the army, and is considered an architect of the Gurkha induction into the British Indian Army. Hodgson is also credited, while already in retirement in Darjeeling, with having convinced a reluctant viceroy to allow an eager Jang Bahadur to participate in the quelling of the Sepoy Mutiny 1857-58.

Ramesh Dhungel: “Hodson was probably the first scholar to get excited about ethnic diversity of the country.” He called in members of ethnic groups from far and wide to the Residency at Lazimpat (from ‘Lodging Part’, according to some) and conducted interviews and meticulously wrote down everything, from linguistic attributes to physiognomy. Dhungel has discovered papers which indicate that Hodgson brought skulls from Nepal and Tibet to England, with accompanying details of ethnic identity, place, sex and price paid.

Wrote Hodgson, “My favourite amusements of the sedentary kind are researches into the origin, genius and attainment of the various singular races of men inhabiting Nepal.”

War party

The resident also kept a steady stream of friendly spies supplying him with the goings among the powerful clans, and his reports to Lord Auckland, the viceroy in Calcutta, reverted as instructions to the Kathmandu government. Through threats routed through Calcutta, he kept in check the ‘war party’ in Kathmandu that wanted to encroach upon Company-held territories in the tarai. For this, he earned enimty in Kathmandu and gratitude in Calcutta.

Worried over the takeover of the state by the military (by then totalling a hefty 19,000 men), and the prospects of inter-clan rivalry for power, he wrote to the Viceroy in June 1837, “Civil wars have rather a tendency to feed than quench martial spirit and power.”

At Carrell No 39 at the British Library, Dhungel has only had time to flip through 65 of the 108 bound (but not catalogued) volumes of Hodgson’s collection. But already he has discovered material of immense importance to Nepali historiography. For example, we know only of the social reforms of Ram Shah and Jayasthithi Malla, but the Hodgson papers clearly point to reforms during the times of Bishnu Malla and Siddhi Narsingh Malla. We know that Makwanpur, Chaudandi and Bijayapur were regarded as separate states by the Gorkhalis, but through Hodgson’s papers, we discover Chainpur too had a status as a rajya. Says Dhungel, “Being from Chainpur myself, I liked that.”

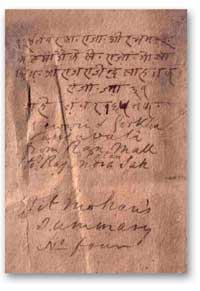

![]() The Hodgson Papers

The Hodgson Papers

Some of the interesting bits of information uncovered by Ramesh Dhungel so far from the Hogdson manuscripts at the British Library.

Anglophile

In 1841, King Rajendra Bikram writes an abject letter to the Viceroy in Calcutta apologising for the belligerent attitude toward the Company and its resident in Kathmandu, and says that “as per the suggestions of Hodgson saheb, we have dismissed those who have tried to bring a distance between our two great governments, whereas we have appointed those who are for friendship between our two great governments.” A list is also provided of the courtiers fired and retained.

Lumbini

Hodgson seems to make one of the earliest references to Lumbini, by referring to “Asocan Laths” (Ashokan pillars) of the tarai, in particular with reference to a site west-north-west of Bettiah, and 20 miles south of the hills. On top of this ‘lath’ is a couchant lion, which has long disappeared from the Ashoka Pillar at Lumbini. Because no sources are provided, Dhungel believes this may have been Hodgson’s own discovery.

Two Dhararas

Two Dhararas

In Hodgson’s own English handwriting (he also wrote in Farsi and in Devanagari), there is reference to two dhararas in place of the one that still stands and is called Bhimsen Stamba. The one named for Bhimsen, writes Hodgson, had 142 steps, whereas there was one taller than this, at 174 steps which was dedicated to Queen Lalit Tripurasundari. According to the historian Baburam Acharya, Bhimsen Thapa had these two towers placed at the entrance of his palace. The earthquake of 1834 seems to have taken a permanent toll of one of them.

Shree Teen Hodgson

At one point, Raghunath Pandit, who had earlier served as a stopgap Bahun prime minister during those turbulent years, writes to Hodgson referring to him as ‘Sri Panch Janaab Hogdson Saheb’. Jang Bahadur himself later went as far as to refer to Hodgson as ‘Sri Teen’, reports Dhungel.

History

History

One continous manuscript 1,200 feet long contains a history (brittanta) of Nepal commissioned by Mathbar Singh Thapa, the flamboyant nephew of Bhimsen Thapa, and prime minister, who was cut down by Jang Bahadur.

Spies

Through his spies in the Gorkhali court, Hodgson accessed a letter which is a demand on the vaccilating King Rajendra Bikram from one faction that so many named courtiers of the other faction must be cut down (“katnai parcha”) by Dasain-time. Their fault, being in cahoots with the British Resident. The words used to villify Hodgson in that letter reflect the mores of the times and come across as shocking today. For, every time Hodgson’s name comes up in the text, he is called with willful use of what was considered pejorative, “Harchanya tharu musalman firingi”. (Harchanya = derogatory Valley-speak for Hodgson.)

Jang Bahadur

Jang Bahadur

In the years after retirement, apparently Hodgson became quite friendly with the post-Kot Massacre Jang Bahadur, and Dhungel has found that Jang even helped Hodgson’s son during his visit to England. After Hodgson went into retirement in Darjeeling, and the Kot Massacre devastated the top layer of Kathmandu nobility, an informant calling himself ‘Pahalman’ writes him a letter in the Avadhi language, which gives a sense of the atmosphere in Kathmandu right after Jang Bahadur took power. Roughly translated, the letter reads, “There is not even 4 anna of security of the 16 anna we used to have when you were here. No one can speak, no one can move about freely. The real king today is Jang Bahadur, and he does whatever he desires. All the paltans are with the brothers, who are placed in Patan, Bhatgaon, Thapathali, Narayanhiti. There are preparations on to invade Tibet. There are no more comings and goings at the king’s palace.”