From Nepali Times (October 16, 2022)

Satyamohan Joshi, who died on Sunday morning at age 103, was a renaissance man, a polymath and historian whose long research career itself spanned Nepal’s recent history.

Among the many subjects he was an expert in, some stand out: Nepal’s devotional temple art, Kathmandu Valley’s syncretic blend of Buddhism and Hinduism, he was an authority on the Newa Civilisation and of the folk culture of the Karnali. In visits to China, he researched Arniko’s history, and as a numismatist he investigated historical coins from the Licchavi, Malla and Shah era.

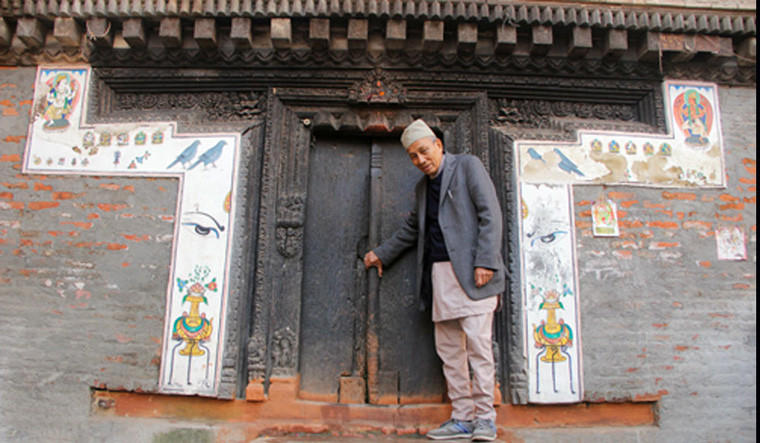

Despite his vast knowledge and the respect the nation showed to him, Satyamohan Joshi was a humble and self-effacing person. Always dressed in his trademark daura suruwal topi he lived all his life in Bakum Baha near Patan Darbar where he was born in 1919. He welcomed visitors sitting crosslegged on a straw mat, usually with his wife Radha Devi.

Till a few years ago, he would walk unassisted along the alleys, and up the steep flight of stairs for meetings of the Bhaidega Reconstruction Committee of which he was chair. He did not speak much, but when he did it was to share his knowledge and to give important suggestions about rebuilding the temple destroyed in the 1934 earthquake. Friends would offer to walk him home at night, and he would refuse, saying: “It’s just around the corner.”

After education at Darbar High School and Tri-Chandra College, the young Satyamohan got his first job at age 23 in the Industrial Survey Office. It was 1943, and the Ranas were still in power. In 1953, the very year that Edmund Hillary was in Nepal to climb Mt Everest, he became the first Nepali to visit New Zealand, about which he wrote a travelogue in which he informed Nepalis about the International Time Zone and Maori culture.

Satyamohan was passionate about investigating, writing and in sharing his knowledge and he was equally prolific in Nepa Bha and Nepali languages. International researchers, and even many Nepali ones, wrote books in English. It is perhaps because his research did not appear in English that someone with such stature within Nepal did not gain deserved attention abroad. But this never bothered Satyamohan Joshi – he believed that it was only if Nepal’s citizens and culture became modern that Nepal itself would enter the modern age.

His interest in data and facts drove him to write the book हाम्रो लोक संस्क्रिति for which he won the Madan Puraskar in 1959. But after King Mahendra’s coup and the overthrow of B P Koirala’s elected government in 1960, Satyamohan also lost his government job.

As member secretary of the Royal Nepal Academy, he started investigating Nepal’s ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity and the Academy appointed him to lead an interdisciplinary team to the remote Sinja Valley, which to this day is considered a model for meticulous field-based research. He also oversaw the production of a dictionary of Nepal’s 14 main languages.

Satyamohan Joshi spent 1965-69 in Beijing, researching the background of Arniko and his many achievements, thus introducing Nepalis to the famous artisan and architect who made his name in the court of Kublai Khan.

While at the Royal Nepal Academy, Satyamohan Joshi supported another of his areas of interest: theatre. He encouraged young and talented actors and singers to take to the stage, paying special attention to the wardrobe during performances. His own drama बाघ भैरव could not be staged during the Panchayat years and was finally performed at Gurukul Theatre in 2006. Satyamohan Joshi was also instrumental in reviving the Kartik Nach dance festival, which had not been performed in 60 years.

When I went to meet him ten years ago at his home in Bakum Baha to research his life and work, tall concrete buildings were already towering over the lush courtyard of his home. As always there were people waiting to see him from early morning. Members of the Patan Chamber of Commerce were there to invite him to their convention, the Kartik Nach committee was also there, a group involved in heritage conservation was waiting for its turn to consult him.

Over the last decade that I continued to visit him, Satyamohan Joshi was always his age-old self – gracious towards visitors, inquisitive about others’ work and ideas, and nurturing towards all aspects of culture and society.

Satyamohan Joshi was a beacon of hope, creativity, and humanity at a time when there is such an absence of integrity in the country. He was always looking at the positive side of things, trying to find solutions, avoided back-biting, spoke directly and to the point, and had the capacity of distilling even the most complex issues into simple terms.

This is why his passing is such a great loss to Nepal and Nepalis.

Adapted from a report in Sikshyak Monthly, October 2012.