From HIMAL, Volume 5, Issue 4 (JUL/AUG 1992)

Arrivals at Goldhap Refugee Camp, 22 -29 July 1992.

Pictures by Laxmi Prasad Luitel

The Bhutanese refugees have a problem. The world outside Nepal does not know they are there. The few that hear of them are told that they are migrants from the Indian northeast, illegal immigrants finally being deported, or that a few are Bhutanese who have left voluntarily after receiving generous compensation from the Thimphu Government.

Foreign Minister Dawa Tshering told the BBC in March 1992 that most of the residents in the camps of Jhapa District in Nepal’s eastern Tarai were not really refugees. Patrick de Silva, who heads the South Asia desk of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR in Geneva, told the BBC that he had witnessed the exodus and had heard from refugees that they were “leaving because they felt there was no place for them.”

Who to believe, the longest serving Foreign Minister in the world or the UNHCR official? A visit to the camps of Jhapa helps to resolve doubts. Every day, for the past few months, 300 to 400 refugees have been arriving in trucks from the roadheads of Bhutan in West Bengal and Assam, says M.A. Awad, UNHCR’s Nepal officer-in-charge.

Sub-Inspector Hom Jung Chauhan, chief of the border post of Kakarbhitta where all the refugees enter Nepal, has no doubts about the origin of the refugees. “The Bhutanese Nepalis speak of ‘Mandal’ (headman) and ‘block’ (village units), words that Meghalaya Nepali would not know. They are also submissive and have peculiar formalities. When they realise that I represent authority, for example, they bow in a very special Bhutanese way.”

Arno Coerver is chief of the Lutheran World Service’s (LWS) refugee operations in Jhapa. Asked about the refugees’ origin, he replies, “All I can say is that 95 to 98 per cent have lived their last year in Bhutan.”

The Refugee Count

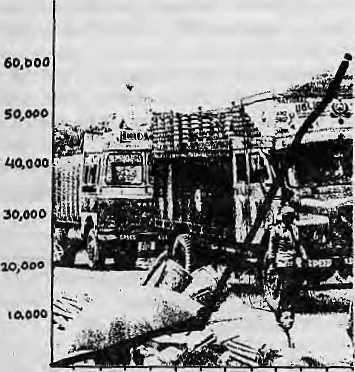

The arrival figures in Jhapa speak of the relentless pace of Thimphu’s eviction programme. The refugee-run Human Rights Organisation of Bhutan (HUROB), which manages the camps, counts arrivals. There were 234 refugees in 1991 July, and an average 1500 Lhotshampas arrived every month since then until December 1991, when there was a sudden dip to 412 arrivals for January 1992 — coinciding with Amnesty International’s visit to Bhutan. Immediately thereafter, the arrival rate shot up to average 10,000 a month, where it remains today.

By 23 July1992, there were 62,723 refugees registered in the six camps of Maidhar, Timai, Goldhap, Beldangi I and II, and Pathan. At the time of going to press, UNHCR estimated 65,000 in the camps.

According to conservative estimates, there are perhaps another 8,000 refugees not in the camps in Nepal and 15,000 living in rented premises or as squatters in Assam and Jalpaiguri District of West Bengal. (Nirmal Bose, prominent Calcutta politician from Jalpaiguri puts this figure at between 25,000 and 30,000 refugees, while refugee sources say there are up 15,000 outside the camps in Nepal.)

A conservative estimate therefore puts the total number of Bhutanese refugees already out of their country at 88,000. As the influx shows no signs of slowing down, UNHCR expects the numbers in the camps to rise from 65,000 to 75,000 by the end of September. The World Food Programme has already been requested to make arrangements for supply of provisions for that number. By the end of the year, says UNHCR, the figure could easily top 100,000.

A few unlikely factors made life a little easier for new refugees. It was reassuring for them to find Nepali-speakers in the Duars and Nepal’s Tarai full of Nepali-speakers. They must have been relieved that the host population was not so hostile. The refugees from Samchi, for example were helped by the labourers of Luksang , Dhumsipara and other tea gardens. Dal Bahadur Rai, who works as a guard, says he and hundred of co-workers raised IRs 10 each on two occassions when the refugees first started arriving.

As they made their way to Nepal, many refugees found that because the Jhapa houses were built on stilts, the underneath made perfect shelters. Because the region is rich in bamboo, the problem of housing was also solved. “Can you imagine the problems of shelter there would be if the camps were in the western Tarai?” Coerver of LWS.

In the beginning, when the refugees were arriving in tens and twenties, they received support from locals in Jhapa. As the numbers swelled, the Nepali Government asked UNHCR to provide assistance, and the agency started work with the Nepal Red Cross in July 1991. In October 1991, UNHCR charged LWS with setting up and managing the camps. In May 1991, ill health, malnutrition and a climbing death rate forced UNHCR to declare an emergency, which released special funds from Geneva. Since June, the work has been divided between LWS, which handles camp infrastructure and feeding, while Save the Children Fund (UK) looks after health and nutrition. A number of other NGOs are also active, from women’s support to physical and psychological rehabilitation – there are numerous victims of rape, beatings, torture, solitary confinements and prolonged imprisonment.

Health in the camps has since improved, but a medical officer of the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta says the danger now is of malaria during the monsoon, and Japanese encephalitis after the rains.

Refugee Diplomacy

Under normal circumstances, persons who flee persecution in one country and enter another are regarded as refugees. But these are abnormal circumstances, in which the Lhotshampa refugees have entered a third country, only to be treated as refugees under international safeguards of the UNHCR. “his a peculiar situation with Bhutanese refugees that you have a corridor to Nepal through Indian territory,” concedes UNHCR’s Awad, who has worked with refugees in the Chad, Indonesia and Thailand. UNHCR is not working with refugees in the Duars and Jalpaiguri in India, the “host government”, has not formally invited the agency.

As for UNHCR’s presence in Bhutan, High Commissioner Sadako Ogata has made three requests to Thimphu to allow a high-level mission to visit Bhutan. Foreign Minister Tshering stopped by in Geneva on 28 July, on his way back from the Olympics inaugural. He told Ogata that he was in close contact with the International Red Cross and Amnesty International, which had recently visited south Bhutan, as had a group of Indian journalists. South Bhutan “is now quite peaceful”, Lynpo Tshering told the UNHCR chief, and he felt it unnecessary for the agency to send a mission.

The camp residents seem to be mostly peasants whose world until eviction was limited to their “gewogs” (villages) and”blocks” (village units). While they were quite aware of the cultural links with the Nepali-speaking world beyond Bhutan, most individuals interviewed in the camps had never visited Nepal and, at best, barely knew where their ancestors had migrated from in Nepal or India. The “Nepaliness” of the Lhotshampa refugee immediately makes his/her identity as Bhutanese suspect in the eyes of those who have not cared to study the country’s peculiar history and the circumstance of Nepali migration. The porousness of being “Nepali” turned a disadvantage for the Lhotshampa as a refugee.

Writers on refugee problems emphasise that there are only three possible fates for long-term refugees. They can be repatriated, they can become assimilated in the “host country”, or they can be resettled in a third country. Only the first two options apply for the Lhotshampas, and refugee leaders are acutely aware of the potential problems of the second. “Our interest lies in as rapid a return as possible because we realise that the longer we stay away, the greater the possibility that the population will give up hope,” says Dr. Bhampa Rai, who heads HUROB.

When repatriation does take place, (such as for the Cambodian and Laotian refugees from camps in Thailand), under ideal conditions there would have to be a tripartite agreement between Bhutan, Nepal and an international monitoring agency such as the UNHCR, with India possibly acting as observer.

The importance of documentation is vital during repatriation, to prove the origin and nationality of a refugee. It is for this reason that, with UNHCR’s help, the Nepali Government on 9 August 1992 started registering the refugees and distributing identity cards. HUROB, meanwhile, has kept its own records listing age, date of departure, land and house registration numbers, reason for leaving, estimated value of property left behind, “compensation” received, as well as photocopies of Bhutanese citizenship ID cards and other relevant documents.

Dr. Rai discounts the possibility of non-Bhutanese entering the camps. He says HUROB organised settlement according to districts and blocks in the home country. A mandal, if in exile, or another senior person establishes contact with new arrivals and maintains records. “It is extremely unlikely that interlopers can get away with claiming to be Bhutanese. Besides, it is not in our own interest to take back more people into Bhutan than the number that came out.”

The relations hip between the locals of Jhapa and the refugees have been civil rather than cordial, And there are potential problems because, by year-end, 100,000 refugees may have settled in a district with a population of 6501,000. Says C.K. Prasai, senior politician of the ruling Nepali Congress party, who lives in Birtamod, “So far, there have not been many untoward incidents. But once the refugees begin to affect the economic well-being of the locals, the situation would be ripe for conflict.”

Jhapa being a district of recently-cleared Tarai jungle andpeopled almost entirely by recent migrants (hillmen from Nepal’s Taplejung, Panchthar districts, plains peoples from the south, Burmese Nepalis of the 1960s and a few that fled Meghalaya in the mid-1980s), the Lhotshampa refugees are more welcome here than they might have been anywhere else. But there is no guarantee that this will last. In the junction town of Birtamod, one can feel resentment just under surface. A bookshop proprietor at the main chowk who has seen more than a thousand Assam trucks pass his shopfront believes many are coming to partake of the easy life as refugees consuming UNHCR rations. He says the local price of essentials has shot up due to refugee demand and, apart from the few who have lucrative contracts to supply the refugee camps, local people are finding life difficult.

While they await return to Bhutan, the refugees can only ruminate over how it is that mid-monsoon 1992 finds them in the humid plains of Nepal’s eastern Tarai. Says Om Dhungel, a civil servant recently arrived as refugee, “If we are being kicked out because our ancestors went into Bhutan as labourers, who is safe? The Indians who were taken as plantation and railway labour a century ago to Fiji, Mautirius and South Africa? Are the they all now to be repatriated?”