From Himal Southasian, Volume 23, Number 5 (MAY 2010)

Having arrived at Manas Lake, under the great snow dome of the mountain Kailash, she took deep draughts from the clear, sweet water. She was tired by the chase given by the herd of kiang, wild asses, which had begun right from the time she had left Nepal at Hilsa. (Understandably, the kiang had felt the need to challenge this odd species that had invaded their habitat.) Suntali went down on all fours and rested by a set of thorn bushes, which kept the cold, biting wind at bay. She thought briefly of the baby she had left behind in the sub-tropical Nepal. But there was no sense worrying – the calf was well cared for, surely, by his extended family of aunts and uncles. No time to worry, for she was the Jogging Buffaloe, her interest and desire just to run, run, run!

Suntali would have liked to do the kora, circling Kailash like the human pilgrims who were milling about her on the lakeside. One such traveller came by and touched Suntali on her back, not quite believing the sight of the hairless, dark-skinned beast here by the banks of Manasarovar. “I am a zoologist from Bengaluru, Dr Venkatesh,” said the man. “And I should know that you, lady water buffaloe, are an aberration in these surroundings. You are far, far from your traditional habitat, by altitude, vegetation, geology and climate.” Prabhavati, the doctor’s spouse, came up and said, “Oh, but doctor, have you not heard of climate change? This is the shape of things to come – before long, yaks will be swimming in the Kaveri!”

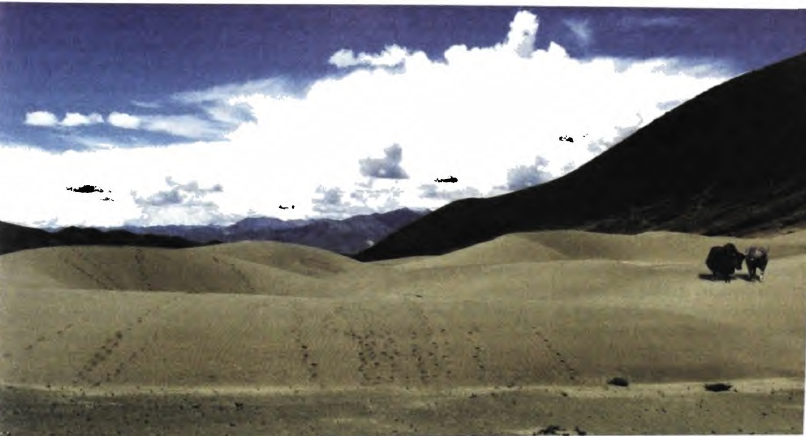

Suntali would indeed have liked to do the kora, but she knew that her broad bovine hoofs were not meant for that high trail of rock and ice. Besides, she was sure to suffer from altitude sickness. Buffaloes were meant to wallow in waterholes, move among the paddies, mostly stepping on mud rather than hard, rocky ground. Their lungs are evolved for lower altitudes. Suntali had been audacious even to have come this far, but certainly she did not have a death wish. She was certainly adventurous, of course, and there was nothing she had liked better than lumbering along the Tibetan flats, letting her imagination run wild amidst the constantly changing scenery. In particular, she had liked watching the shapes of mountains transform as she progressed. With Kailash, she would be missing this, having decided to forego the circumambulation.

She was an atheist buffaloe, of course, and so would not have done the kora because of religious belief. She would nevertheless have liked to have done the parikrama because … why, after all? “Because it is there”? No matter that George Leigh Mallory had used that same enigmatic sentence when asked why he was seeking to climb Mount Chomolongma, back in 1924 or so. There is no reason why such a good rationale should be monopolised by a single long-dead mountaineer, thought Suntali, as if no one thereafter could have the opinion expressed in the same word sequence! How absurd.

But then there is a lot of absurdity about, like those who think it’s not okay for a water buffaloe to run as a hobby, for fun. As if buffaloes have to keep to the sub-tropics, that their loyalty has to be limited to muddy ponds. If the skin has to be kept wet, why can’t showers be arranged? Why should animals stay within the bounds created by natural evolution and society’s construction, given that everything is changing at such a clip? As long as you do not harm someone or something else, you should be unbound, free to do what you desire. Freedom for those who choose to exercise it! was Suntali’s guiding philosophy, which leaves those who choose not to exercise that freedom well within their rights as well! Freedom to decide one way or the other made all the difference between being an animal and an inanimate object.

The way east

Suntali now thought about the next leg of her travels, which meant heading eastwards. The plan was to jog along the flow of the Tsangpo River, keeping the march of the Himalayan peaks to the right. She would reach Ganesh Himal, which is approximately north of Kathmandu Valley, and then take the Trisuli River southwards. But where to start? It was desert terrain to the east as far as the eye could see, and one could easily make a mistake and end up in Mangolia.

Just then, trail advice arrived in the form of a huge, lumbering yak, bigger even than Suntali – when he snorted, the marmots in a hundred-yard radius ran for cover, diving into their holes. His size was exaggerated by the coarse brown and white hair that covered his body, cascading down in dreadlocks that dragged along the ground. The smell was overpowering, a kind of aroma that males of some species, such as he-goats, tend to exude. Suntali found herself liking it somehow, and certainly the stench kept the inquisitive human pilgrims away.

The yak started a conversation rather diffidently, incongruous for such a large creature. “Err, I have always wondered which spelling to use,” he said, “buffaloe with an ‘e’ or buffalo without the ‘e’.”

“Either spelling is fine,” replied Suntali, adding, “As long as we are talking English, of course.” Introductions made, she asked him the way east.

The highland bovine and lowland bovine reached immediate rapport. His name was Ramaswamy, hilariously inappropriate for a wild yak of the Changtang plain. He did not know why he did not carry a more culture-specific name, such as Tshering, Dolma, Kesang, Tsewang or Tashi. But Ramaswamy knew his geography, and pointed out the great Gurla Mandhata snow massif to the south, beyond which lay the far-west of Nepal and Kumaon of India. He explained to Suntali what was unique about this area, at the base of the mountain Kailash. The four great rivers of Southasia originated here, he said: “The Tsangpo, which becomes the Brahmaputra when it enters Arunachal and Assam; the Karnali, which later becomes the Ghaghara; and the Indus and Ganga.”

“Wow! Kasto gajab!” exclaimed Suntali, who tended to get carried away by such geographical revelations.

Ramaswamy was a highbrow highland bovine, who knew somewhat more than was required for a life of grazing the high plateau. He educated Suntali about the Bon religion, which predated Buddhism; about Tenzin Gyatso the 14th Dalai Lama, who lived in Dharamsala, “about 450 kilometres as the Siberian Crane flies from here, to the west.” And about the Indian pilgrims, like the doctor couple from Bengaluru, who come on guided tours organised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in New Delhi. “That’s probably how I got my South Indian name, incidentally,” said Ramaswamy.

And so, together, the yak and buffaloe jogged eastward. Whenever a verdant pasture showed up, they would take leisurely breaks, graze and masticate some, and move on. At night, they would snuggle together to conserve warmth, among other things. Ramaswamy would always take the windward side. Perhaps for the first time, Suntali understood the value of companionship, of sharing thoughts and space. But she also knew that the time of separation would come, and steeled herself for the parting. For his part, Ramaswamy knew Suntali could not stay back in the Changtang. Howsoever adventuresome, the buffaloe did not have the physique to survive the Tibetan winter. Furthermore, she was the Jogging Buffaloe, who would never be happy in one place. And Ramaswamy’s own physique would not allow him to descend to the midhills and lowlands, where Suntali was headed.

After a few more days, the two travellers came upon Kyarung, an outpost that looked down the valley of the Trisuli. Ramaswamy recited a bit of history: “It was in 1858, and the Kathmandu raja was acting up. The Tibetans forces, helped by the Chinese, swooped down from here all the way to near Kathmandu. The Nepalis sued for peace.” In this area of former conflict, the governments of Nepal and China were collaborating on a project to connect the Tibetan plateau with the midhills and plains. A motorable track now connected Kyarung with the Prithvi Highway, which led to Kathmandu. Said Ramaswamy, “The Chinese gave the Nepali authorities foreign aid to cut the road, which means that you can now walk this route. You would never have been able to do it on the earlier foot trail.”

By the stone walls of Kyarung village, Ramaswamy showed her the way downriver into Nepal. Suntali started on the trail, not looking back. Goodbyes are the hardest thing of all, especially when the law of probabilities suggests you would not meet again. When she was far down the mountain flank, she did take a peek backwards, and saw the figure of Ramaswamy on the ridgeline, his girth making a fine silhouette against the orange evening sky.

Momo mission

The road led down the east bank of the Trisuli, past the settlement of Syabru Besi, the river making a deep cut where mountain walls reared up on both sides. At the district headquarters town of Dhunche, Suntali saw people crowding around stalls which had tiered aluminium containers spewing steam. Small dumplings were picked out from these, which the humans were dispatching with relish. This was the dreaded momo, the meat dumpling of the Nepal Himalaya. It was weird – cow and bull slaughter was not allowed by law in Nepal, but their bovine cousins, the yak and buffaloe, were fair game. The yak was not yet a product for mass market consumption, but the buffaloe was hardly left alone by the momo industry.

Not a little perturbed, Suntali sought consolation in the changing climate. She could already feel the humid warmth of the tropics reaching out to her, and she allowed herself a wallow in a paddy field being prepared for planting. Now she saw water buffaloes, cows, bulls and midhill goats all along the trail, some grazing free, others being stall-fed. The festival of Dasain would be up after the monsoon, at which time these goats – or, rather, their goose – would be cooked. Suntali was not above black humour: we have only one life to live.

The buffaloe continued her jogging, past Betrabati village, the hydropower-producing town of Trisuli, finally arriving at the Prithvi Highway, at Galchi. This was the road that linked the Kathmandu Valley to the Tarai flatlands and India, a lifeline that brought in everything from cement and consumer goods to iron rods – and buffaloes.

Walking upcountry towards Kathmandu along the roadside, Suntali now came upon a terrible secret that was to change the entire rationale of her travels, making it a mission of great urgency. This highway was evidently a roadway of death, a conveyor-belt of a concentration camp. Truckload after truckload of aged buffaloes were being transported from the plains, and from far and wide in the Indian plains, to satiate Kathmandu Valley’s taste for meat-filled momos.

True, humans need protein, and perhaps they could do nothing else other than to have meat until alternative protein content was provided. It may also be a matter of evolutionary desires of a carnivore species. Also true, the ‘original’ Kathmandu momo had to be sourced from buffaloes, and not latter-day interlopers such as chicken or vegetable or paneer. But do they have to transport them so, Suntali demanded voicelessly, as she saw truck after truck transporting miserable sisters and brothers to the slaughter houses of Kathmandu. They were packed in like sardines, ropes were looped round noseholes and tied to roof beams, so that none dare to collapse to the floor. The cruelty was abominable, just as elsewhere Suntali had seen chicken being transported with their feet tied to bicycle handlebars, heads scraping the ground.

Something had to be done. Suntali abruptly changed direction. There was no sense going up to Kathmandu: emancipation was what she would engage in.

Suntali was a healthy buffaloe, unlike the skinny buffaloe in the trucks, and looked well cared for. Everyone thought she was a grazing bovine from a nearby village, so they left her alone as she walked urgently down the highway. She came upon a truck that had stopped to unload a passenger who had collapsed and died, the body taking up too much space. When the driver and handler were looking away, Suntali quietly went up the ramp and used her teeth to untie the ropes that tethered the inmates to the roof beam. At first too scared to move, the animals soon understood what was going on, and then silently, excitedly trooped out. They dispersed into the surrounding hillside, some going down to the river to take deep draughts from the Trisuli.

It took no more than three days for the momo market in Kathmandu to collapse. There just were not enough buffaloes in stock, and the conveyer belt had been sabotaged. But no one knew exactly what had happened. Some truck drivers reported an apparition of a buffaloe suddenly appearing, forcing them to swerve and come to a halt. Then somehow the buffaloes were let loose. Nobody believed the drivers’ story that some intelligent bovine was behind all this, but the fact was that there were now buffaloes all over, going feral in the jungles of central Nepal. Parked buffaloe transports were being mysteriously emptied in truck stops all the way to the Indian border, from Mugling to Narayanghat, Lothar, Butwal, Birgunj and Bhairawa.

Since Kathmandu Valley was the prime market for buffaloe meat, the entire buffaloe socio-economy of the northern half of the Subcontinent had changed in one stroke. The train of trucks that collected aging buffaloes from all over, funnelling the creatures up to Kathmandu stood suddenly cancelled. True, a carnivorous human tradition had been abruptly halted in Kathmandu, but water buffaloes in a large part of Southasia suddenly breathed easier.

There was great disquiet in the human world. Was this the beginning of an animal uprising? No one knew, because no one knew the cause behind the Great Southasian Buffaloe Emancipation. One thing was certain: Southasia would never be the same again. And only you and I know how it all came about. There was this buffaloe, as you know, who liked to jog…

Editor’s note: The writer is non-vegetarian.