From Scroll.in (19 May, 2020)

Kanak Mani Dixit & Tika P Dhakal

At a time when Indian and Chinese soldiers have been squabbling at various border points, a sliver of mountain terrain thus far familiar only to Kailash-Manasarovar pilgrims has suddenly come into focus for the media and public in India – the area around a place called Lipu Lek.

Most national security experts around the Subcontinent are hearing about Lipu Lek for the first time too, even though this has been a long-standing issue between Kathmandu and New Delhi, suddenly given a higher profile by the Narendra Modi administration. Nepal has wanted to work out the matter quietly. But three recent actions by New Delhi have complicated the prospect of talks – firstly, in early November 2019, a newly issued official map by India’s Home Ministry included the Kalapani area that Nepal regards as its own, which created a ruckus in Kathmandu.

Fast on the heels of this cartographic adventure, fully alert to Kathmandu’s view on the matter and amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh on May 8 “inaugurated” a jeep track towards the high pass called Lipu Lek at 17,000 feet height, above the place called Kalapani. Then, on May 15, Indian Army chief Manoj Mukund Navarane imputed a China angle to protests made by Nepal.

Another South Asian hotspot

Why this display of India’s prowess at this time? Was it a message to the people of Nepal, who rose up against a five-month blockade of 2015-’16, imposed by New Delhi because Kathmandu did not heed its directives as it promulgated the new Constitution in September 2015? Or was it aimed instead at Nepali Prime Minister KP Oli at a time when he is politically isolated?

Whether deliberately or egged on by non-political lobbies such as the Indian security establishment, the Modi administration has created a schism that has led to tit-for-tat response from the Nepal government at a time when fence-mending between the two countries was actually progressing well. On Monday, Nepal’s Cabinet decided to approve a new map that showed the country’s territory including a 335 sq km strip north of Kumaon.

In its own actions, New Delhi seems not to have taken into consideration the possibilities of escalation, and the myriad aspects of a unique bilateral relationship: after all, political stability and economic growth in Nepal is critical also for the populous adjacent states of India. Instead of judicious, behind-the-scenes negotiations after the November controversy, India has moved to create another hotspot in South Asia.

Within the region, Nepal is a unique neighbour of India. Nepali citizens serve in India’s Gorkha regiments. Up to 1.5 million Nepali migrants work as an underclass in India’s informal economy – mainly because Kathmandu has not been able to deliver secure livelihoods through good governance.

Nepal and India share an open border that is distinctive in South Asia. Nepal provides employment to hundreds of thousand of Indian labour migrants and is the seventh-largest remittance source to India’s economy – that too, to the poorest parts stretching from eastern Uttar Pradesh through Bihar to Orissa. But now, “shared prosperity”, the term that finds place in repeated bilateral declarations, stands threatened.

While New Delhi’s political class stoutly defends the Indian government’s actions, it does not seem to be fully aware of the historicity of the Lipu Lek region. Did Narendra Modi’s passion for Himalayan shakti peeths – shrines to powerful deities – allow him to ignore Nepal’s territorial concerns while pushing through a motorable route to Kailash-Manasarovar? Meanwhile, it would be most unfortunate if the Indian Army has played a role in this escalation, as the successive actions of the Indian defence minister and Army chief seem to indicate.

Historicity of Lipu Lek

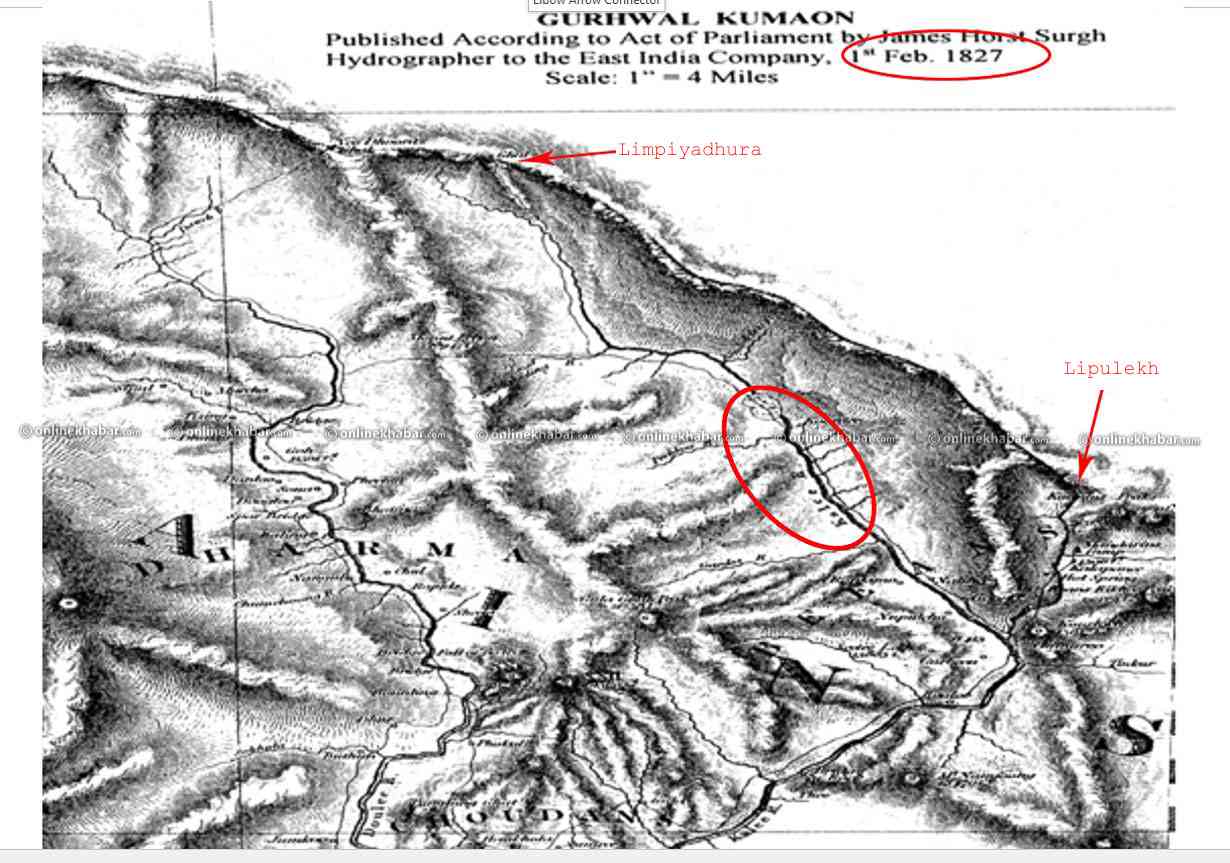

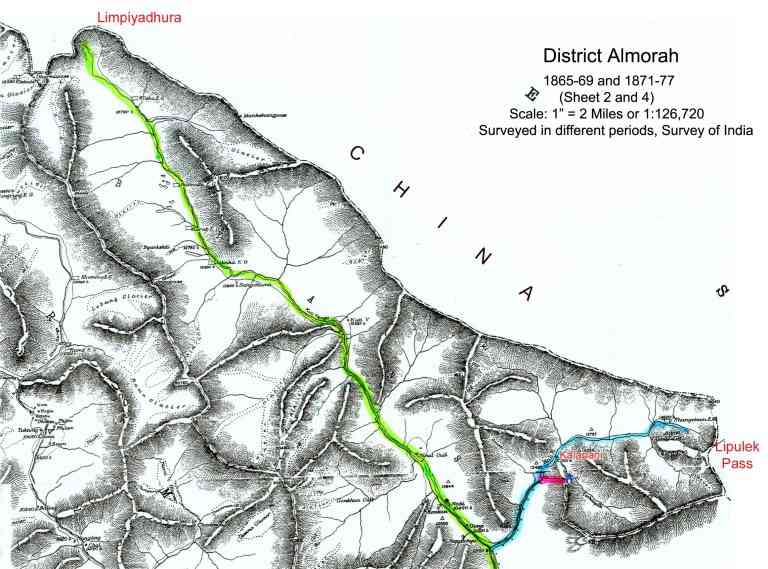

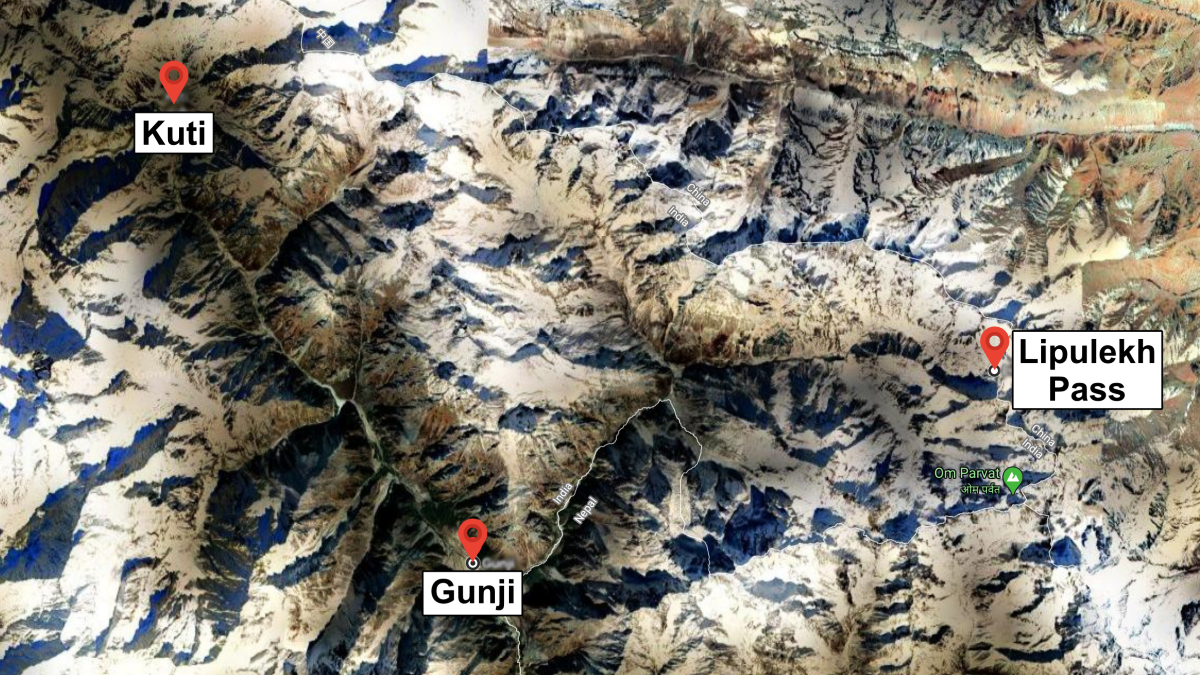

The current controversy centres on three locations: Lipu Lek, Kalapani and Limpiyadhura. They form a triangle in Nepal’s northwest, with China/Tibet to the north and India’s Kumaon to the south. The area is watered by the upstream Mahakali river. “Lek”, sometimes spelt “lekh”, in the Nepali language denotes mountain flanks just below Himalayan ramparts.

Neglected by the Kathmandu durbar for decades, it is only with recent scholarship, after the advent of democracy in Nepal in 1990, that scholars have been able to be vocal about the historicity of the area.

With the expansion of the Nepali state, started in the mid-1700s by founding king Prithvinarayan, about to surge past the Sutlej river, the East India Company started a multi-pronged campaign against Kathmandu. The Anglo-Nepal War (1814-’16) ended with the Treaty of Sugauli that also demarcated Nepal’s boundaries, with Kathmandu ceding Sikkim and Kumaon Garhwal.

The Sugauli Treaty specifically stated that the Kali was the Western boundary river, with all areas east of it being the nation-state of Nepal, the Kumaon region of British India lying on the other side. The proper boundary therefore depends on identifying the Kali to its source. Starting in the 1820s, the British produced maps that identified the main stem of the Kali river as turning northwest at a point deep in the mountains upstream from Garbyang, heading towards the headwaters of Limpiyadhura.

A rivulet (or khola) branches north and northeast at this turning point, named Lipu Khola in some maps, continuing past Kalapani to the base of the Lipu Lek pass. The main flow of the Kali nadi to the northwest, meanwhile, contains three highland villages in a line – Gunji, Navi and Kuti, which the Nepali state had considered as its own. A census was conducted in this area in 1953, parliamentary elections were held in 1959, and land registration records from here were kept at the Darchula district office.

When the East India Company realised the value of Lipu Lek for trade with Tibet and understood it to be the main pilgrimage route to Kailash-Manasarovar from the Ganga plains, it seems to have got acquisitive. After producing successive maps identifying the Kali as the rivercourse going up to the Limpiyadhura heights, maps published by the Company after 1860 suddenly began to identify Kali as the rivulet (Lipu Khola) that came down from Lipu Lek.

For various reasons, Nepal’s Rana rulers were not in position to object to this sleight of hand, even after having supported the British to quell what was known as the “Sepoy Mutiny” of 1857. Sparsely populated and offering only the pilgrimage route to Kailash-Manasarovar, this area remained neglected, including by Kathmandu’s nobility.

In 1950, as Nepal emerged from under the Rana shogunate, China was making inroads into Tibet. A worried New Delhi convinced Kathmandu to let India place 18 military posts along Nepal’s northern frontier. It was only in September 1969, under King Mahendra, that Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista was able to negotiate the evacuation of those posts. One was quietly allowed to remain, however, and the speculation is that this was in the place known as Kalapani, south of Lipu Lek and east of Lipu Khola. This was probably a temporary concession to India, given the heightened sensitivity of the high pass following the 1962 Sino-Indian war.

While New Delhi may want to debate the ownership of the Limpiyadhura strip, Kalapani itself is on the east bank of the diminutive Lipu Khola, which the latter-day British officials decided to christen the Kali (which is also to the liking of the present-day Indian administrators). This is why the Nepali position on Kalapani has been strident, while the demands regarding the strip up to Limpiyadhura are more recent and following scholarly revelations.

Nepali tropes

One does not know of the understanding between King Mahendra and India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, but the Limpiyadhura triangle remained in limbo, in the northwest corner of Nepal. The Panchayat era from 1960 until 1990 was a time of closed society, with administrators directly reporting to the Narayanhiti Royal Palace. Both King Mahendra and his son King Birendra seem to have decided to keep quiet regarding the area in question, and their many vulnerabilities vis-à-vis India.

The royal autocracy kept the strip towards Limpiyadhura off the government maps, and this is what created difficulties for the Nepali narrative. Meanwhile, the Nepali public got used to maps without the Limpiyadhura triangle, actually following the post-1860 cartography propagated by the British.

This is opposite the experience, for example, of India where New Delhi claims Aksai Chin as the eastern part of Ladakh though it has been in Chinese possession since Independence. Through the publication of official maps, Aksai Chin continues in the Indian public’s imagination as part of modern India’s geography.

It is noteworthy that while the Panchayat autocracy in Nepal was silent about the triangle in the northwest, the elected governments under democracy post-1990 have not let go of what some Nepalis call the”‘Kalapani agenda”, supported by scholars who had looked up the British-era archives. Meanwhile regular communications with New Delhi have kept the matter current. Successive Nepali governments have discussed Kalapani with New Delhi, though without breakthrough.

Especially important in this context were the talks held in New Delhi between Nepal’s Prime Minister Grija Prasad Koirala and India’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee in July 2000. Both sides had agreed to conduct a field survey to demarcate Kalapani. A Joint Boundary Committee was given the task of providing reports using new strip maps, but New Delhi refused to withdraw troops from Kalapani. This left the issue hanging.

In 2015, Nepal’s Prime Minister Sushil Koirala protested the India-China agreement on Lipu Lek. For his efforts, the soft-spoken Koirala was pointedly not invited during his tenure to India for an official visit

Nepal’s initial demand thus was limited to getting the Indian Army garrison out of Kalapani, whose status as Nepali territory could not be questioned even under the existing Indian position, being situated to the east even of Lipu Khola. As new research found relevant maps and reports, and as it became possible to speak freely in the democratic era after 1990, the demands on Limpiyadhura gained momentum.

Sugauli Treaty is key

Nepali sentiment occasionally boils over and there are calls for resurrection of “Greater Nepal”, recalling the all-too-brief halcyon days when the country extended east-west from the Teesta to the Sutlej. This agenda has not been picked up by mainstream polity, but the Limpiyadhura campaign is not part of that trope – it is simply a matter of reading the language of the Sugauli Treaty and identifying the true upstream stem of the Kali River. No subsequent pact has superseded that document in terms of this part of Nepal’s frontier.

Former Nepali Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista told one of the writers of this article the following shortly before he passed away in November 2017: “There is no written agreement between King Mahendra and Prime Minister Nehru that India can produce. King Mahendra is long dead and the political system itself has changed in Nepal. Neither side has produced papers from the archives as such while the public rightly wants resolution. In absence of papers, there is no other way but to define the border according to words of the Sugauli Treaty.”

In May 2015, came news from the India-China summit in Xian that Indian Prime Minister Modi and the Chinese President Xi Jinping had signed an agreement to use the Lipu Lek pass for trade between the two countries. The Nepali reaction was swift, with Kathmandu putting out an official statement:. “The Nepal government is clear about Kalapani being part of Nepal’s territory.”

At the negotiating table, the Nepali side will obviously be asked why it went along for decades with an official map that does not carry the Lipu Lek-Limpiyadhura region. But Nepal was not a democracy till 1990, and for its own reasons the royal autocracy preferred not to challenge New Delhi. For example, in 1969, Hrishikesh Shaha, a Member of Parliament at the time, was fobbed off by King Mahendra when he tried to broach the subject.

Bureaucrats from the Survey Department and district administrators who sent reports of Indian activity on the Limpiyadhura triangle to King Birendra’s palace secretariat received similar responses. It was only after the 1990 opening that archival records and bureaucratic experience began to see the light of day.

At the very least, given the availability of archival records going back to East India Company times, it should be possible for sober minds to consider the historicity of the Limpiyadhura triangle and consider possible diplomatic solutions. Land boundary issues come with a lot of nationalist populist baggage, so they invariably take decades to sort out, and exact huge socio-political, geo-political and economic costs. The goal for Nepal and India at this stage should be to step back rather than rush forward.

Why now?

Given that there was already the map controversy of November 2019, the Indian government would have been fully aware of Nepal’s position when, on May 8, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh from his office in New Delhi digitally opened a track towards Lipu Lek, which would traverse 19 km of territory Nepal considers its own.

At 11.23 am that day, Singh tweeted: “Delighted to inaugurate the Link Road to Mansarovar Yatra today. The BRO [Border Roads Organisation] achieved road connectivity from Dharchula to Lipulekh (China Border) known as Kailash-Mansarovar Yatra Route. Also flagged off a convoy of vehicles from Pithoragarh to Gunji through video conferencing.”

It isn’t clear why India felt the need to conduct this “inauguration” amidst the Covid-19 crisis, and when the road work is not even complete. Clearly, the event was organised with great deliberation, which may help explain the motivation.

Most likely, it was an attempt by New Delhi to create facts on the ground, a fait accompli, in the belief that Nepal could not do much else besides vent profusely and send notes of protest. But was anyone in New Delhi considering the geopolitical, economic, social and even cultural ramifications of the action? If it was a demarche at the behest of the Indian Army with its exclusive focus on security, then the political leadership could have acted to override it.

New Delhi knew that Nepali Prime Minister KP Oli had become politically weakened lately, due to poor governance on the part of his administration, but also because the Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal (“Prachanda”, co-chair of the ruling Communist Party of Nepal) has pulled all stops to bring him down. It was Oli who had stood up to India during the 2015-’16 blockade, but then, the word in Kathmandu was that he and Modi had developed good personal rapport over the past two years.

While there have been angry calls within Nepal to internationalise the issue, to go to the International Court of Justice or the United Nations, and to challenge China and India simultaneously, there is recognition that doing so would be a path of no return – something many believe Kathmandu cannot risk. Hence, Oli had sought to tread carefully, at first resisting pressure to publish an updated map that had already been prepared in January, hoping New Delhi would join talks as promised.

Kathmandu’s reaction

The Nepali reaction to the Lipu Lek action by India can be divided into three parts: that of the public, the government and the political opposition. As could have been expected, the Nepali media and social media erupted in anger on the afternoon of May 8, as soon as Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh posted his “link road” tweet.

The next day, Nepal’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs put out a statement expressing regret at India’s action: “…as per the Sugauli Treaty (1816), all the territories east of Kali (Mahakali) River, including Limpiyadhura, Kalapani, Lipu Lekh, belong to Nepal”, it said. This position had been “reiterated by the Government of Nepal several times in the past, most recently through a diplomatic note addressed to the Government of India dated 20 November 2019 in response to the new political map issued by the latter”.

Kathmandu also called on New Delhi “to refrain from carrying out any activity inside the territory of Nepal”. It noted: “Nepal had expressed its disagreement in 2015 through separate diplomatic notes addressed to the governments of both India and China when the two sides agreed to include Lipu Lekh Pass as a bilateral trade route without Nepal’s consent in the Joint Statement issued on 15 May 2015 during the official visit of the Prime Minister of India to China.”.

Nepal, continues the note, believed in resolving pending boundary issues through diplomatic means, and the government had twice proposed dates for the meeting of the foreign secretaries of the two countries “as mandated by their leaders”, to which the response from the Indian side was still awaited.

In the last paragraph, the note recalls that the Eminent Persons’ Group constituted by the two governments had prepared its final report, meant to “address outstanding issues left by history”. (The group was expected to bring the bilateral relationship up-to-date, given the many changes in the bilateral relationship since the signing of the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship.)

Indian PMO’s hesitation

While Oli has been ready to receive the report, the unspoken reference in Nepal’s Foreign Ministry note is to the fact that even though the Eminent Persons’ Group has prepared its consensus report over two years ago, the Prime Minister’s Office in New Delhi has been unwilling to host a meeting to hand over the report to Modi.

The political opposition in Nepal is today made up of the opposition parties as well as, incongruously, a phalanx within the ruling Communist Party of Nepal itself, led by the Maoist co-chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal. While the main opposition, the Nepali Congress, issued a strongly-worded statement, Oli’s comrades in the CPN leadership have not let this opportunity pass to take him to task, as keen to flay him as to castigate New Delhi.

Under mounting pressure from within the party and outside it, and in order to maintain his command, Oli finally upped the ante with India by having President Bidhya Devi Bhandari (in her “Policies and Programmes” address to Parliament on May 15) read out the plan to publish the new government map. Then on May 18, in a historic move that is bound to raise New Delhi’s ire, the cabinet approved the new national map of the country, firmly including the Kalapani-Limpiyadhura-Lipu Lek triangle.

New Delhi’s response

India’s comeback on the Nepali note, issued the same day, starts with the claim that “the road section in Pithoragarh district in the State of Uttarakhand lies completely within the territory of India”. The road follows “the pre-existing route used by the pilgrims of the Kailash-Mansarovar Yatra”, it says, though this itself is no proof of territorial possession.

However, there is some hope for resolution in the wording of the next paragraph: “India and Nepal have established mechanism to deal with all boundary matters. The boundary delineation exercise with Nepal is ongoing. India is committed to resolving outstanding boundary issues through diplomatic dialogue…”

The statement goes on to say that planned foreign secretary level talks will be held once “the two societies and governments have successfully dealt with the challenge of Covid-19 emergency”.

The reference to resolution of outstanding boundary issues through diplomatic dialogue provides a window, though Nepal’s Foreign Minister Pradeep Kumar Gyawali asks, “If the ‘inauguration’ of the road could happen during Covid-19 crisis, why can’t we talk on this important matter during the lockdown?”

The reference is to a bilateral mechanism headed by foreign secretaries of the two countries, which was to have met to discuss outstanding boundary issues, as decided during Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar’s visit to Kathmandu in August 2019.

Since this mechanism for dialogue had already been established, the escalation by the Indian side in November 2019 and May 2020 must be explained. Further, New Delhi does seem to apply different standards when it comes to different parts of the Himalayan frontier, bending before the powerful and running down those it considers weak.

Raising the volume

While India maintains Aksai Chin on its map, it certainly has done nothing about China’s possession for six long decades. On the other side of Nepal, at Dokhlam on the Bhutan-Sikkim-Tibet interface, India has made a lot of noise but accepted the status quo. On Lipu Lek, confronted with evidence that is available in the archives and official correspondence, and despite Kathmandu’s desperation for talks, New Delhi prefers to go ahead and establish facts on the ground.

Till last week, there still seemed to be some space left for quiet diplomacy. But then the Army Chief Gen. Naravane spoke up on May 15, wading in where the politicians were reluctant to tread. Continuing the trend towards politicisation of the Indian Army started by his predecessor, the general said: “The area east of Kali river belongs to them [Nepal]. The road that we built is on the west of the river. There was no dispute. I don’t know what they are agitating about.”

He added, pointedly: “There is reason to believe that they might have raised the issues at the behest of someone else and that is very much a possibility.”

It may be an indication of changed geopolitical dynamics of South Asia that an Indian Army chief decides to overlook the fact that citizens of Nepal serve in his force, from Assam to Kashmir. (Citizens being employed in foreign armies is acutely embarrassing for Nepal, but it is accepted as a residue of history, and because Kathmandu’s rulers have been unable to provide employment to its people.) In addition, Gen. Naravane is an Honorary General of the Nepal Army, a reciprocal arrangement where the Presidents of India and Nepal invest the respective army chiefs.

Beijing’s resounding silence

Beijing has been silent on the Kalapani controversy since it erupted in early November, even though it can be said to have contributed to the dispute for acting carelessly on Lipu Lek earlier and having signed the trade route agreement in May 2015. To be kind, some suggest that Beijing “may not have known”, but such institutional memory loss is hard to contemplate for a Himalayan pass looking down on Tibet, a region that Beijing is hyper-sensitive about.

The public opinion in Kathmandu and official stance of Nepal also should have made Beijing more circumspect, unless its intention was to appease New Delhi at the cost of Kathmandu. In the give-and-take with India, Beijing’s inscrutable commissars may have underestimated the displeasure the agreement would trigger in Kathmandu.

Thus, Kathmandu is today in the unique and awkward position of simultaneously standing up to both Beijing and New Delhi, having placed its position on Lipu Lek unequivocally before each government. This extraordinary situation was exemplified in an effigy-burning in Gorkha district on May 11, when images of Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi were torched at one go, and KP Oli’s for good measure. The student wing of the Nepali Congress, the main opposition party, carried out similar protests in other districts.

Having kept silent on the entire matter since November, the spokesperson at the Foreign Office in Beijing will have to speak up before long. The Indian Army chief’s statement would require it, if not the disquiet in Nepal about the Chinese position on Lipu Lek.

The clear reference to China by Gen. Naravane also frustrates Kathmandu’s efforts to have separate lines of communication with the two powers. One would like to believe that the Indian Army chief was simply being uncaring about Nepali sensitivities, but did he not know of the agreement signed by Modi and Xi on Lipu Lek when he implicated China?

Towards status quo

The Nepal-India relationship did not need this canker. With New Delhi’s abrupt actions, for reasons best known to itself, and the Nepal government having announced its cartographic response, de-escalation has become an imperative. Nepal cannot afford extended standoff with the southern neighbour, and a volatile relationship along the Himalayan rimland negates India’s own attempts at securing itself.

Without doubt, Nepal is doubly important to India in times of a resurgent China, which actually has been accelerating its diplomatic and economic engagement in Kathmandu. Hence, the reason to ask why New Delhi has chosen to push Kathmandu against the ropes at this time, when it should also be accelerating in its programmes of development cooperation, and, further, working with Nepal to tackle the fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic on South Asia as a whole. It is also a fact that the Nepal-India relationship was on the mend over the past four years since the blockade, until this abrupt diversion.

It goes without saying that, given the crisis that has overtaken the bilateral relationship, Modi and Oli must talk on the phone right away and diffuse the tension. But for now, the word that has arrived in Kathmandu is that “Modiji is incensed.”

India is quite capable of resolving frontier disputes when it wants to, the proof is there in the resolution of the issues with Bangladesh – maritime dispute as well as the chit mahal enclaves on both sides. The task was completed with admirable diplomatic legwork in 2015, but the matter was made relatively easy because of the possibility of territory swaps.

While Nepal-China border issues were mostly resolved by the 1960s, New Delhi and Kathmandu have been working diligently over the last decade to resolve disputes along the open ‘das gajaa’ frontier. There should have been satisfaction that there were only a few border disagreement remaining to be resolved – Susta of Nawalparasi district and Maheshpur of Jhapa district as the major ones, besides Kalapani-Limpiyadhura. Instead, the two countries have suddenly got enmeshed in a crisis.

In the case of the Limpiyadhura strip, New Delhi has moved in a way that makes it difficult for it to back out, particularly in view of the can-do, will-do image Modi has cultivated for himself. At this crisis-ridden moment, it is unlikely that a dramatic resolution will emerge. De-escalation is required, and as the country which made the first move, India must agree to maintain status quo at the Limpiyadhura strip by halting further work on the ‘link road’. An additional goodwill gesture – which had even seemed possible till lately – would be to evacuate the Kalapani military post from Nepali land to an area firmly within Indian territory.

Dialing it down

Further, Kathmandu and New Delhi should not allow a further hardening of positions on Limpiyadhura, while delinking this matter from the myriad other issues that make up the layered and textured relationship between the two countries. Such delinking of a disagreement from the continuous social, political, geopolitical and cultural flows between countries that are embroiled in controversy happens all the time, and should be applied in the Limpiyadhura context.

To begin with, we need a silent agreement that responsible officials on both sides refrain from further statements or declarations that could spoil the atmospherics for negotiations. Meanwhile, in time, a modality can be developed for Indian pilgrims to take the Lipu Lek route, even though this would mean great loss of business for Nepal, whose Humla district is used by many of them presently to access Kailash-Manasarovar.

As the dust settles, there will come a time when Nepal and India can finally sit down and study the maps and historical commitments, while mindful of each other’s security needs in this strategic area. The time and energy saved through de-escalation can be used by both sides to go back to the archives, and to consult experts on identifying the ‘main flow’ of rivers as they reach up to the headwaters.

The final words for this article, regarding the all-important matter of what the Treaty of Sugauli says and which is the true source of the Kali river, must come from Nepali geographers Mangal Siddhi Manandhar and Hriday Lal Koirala, who together wrote the following conclusion to a paper published in the June 2001 edition of The Tribhuvan University Journal:

“The Sugauli treaty has determined the river Kali as the western boundary of Nepal with India. No other boundary treaty with India has taken place changing the river Kali as the boundary except for some land exchange for Sharada Barrage construction. The boundary decided by the Sugauli Treaty remains valid as long as it is not changed by mutual agreement. Maps published unilaterally not in confirmation with the treaty carry no validity. It is beyond any doubt that the river flowing down Limpiyadhura is the Kali River. No cartographic manipulation or misnaming can hide the truth. Attempts to claim the land based on continued use has already been rejected by joint agreement between India and Nepal, in the process of demarcating boundary in the east. Inability of the Government of Nepal to establish an effective administrative set up in all the lands east of the Kali in spite of the treaty provisions should not be made the basis for further encroachment of Nepali territorial space. Relationship between friends should be based on the principles of international law and mutual respect for each other’s sensibilities.”

Kanak Mani Dixit is a writer and journalist, and founding editor of the magazine Himal Southasian.

Tika P Dhakal is a political analyst and columnist based in Kathmandu.