From Nepali Times, ISSUE #274 (25 NOV 2005 – 01 DEC 2005)

Not everyone likes it when the south comes on top

Maps define the boundaries of our physical lives and give us inflexible notions of the spaces we inhabit. The national weather forecasts stop at our frontiers, the rivers flow into or out from terra incognita.

Meanwhile, territory lost long ago remains in the schoolbooks out of wounded pride, giving the population a false notion of the shape of the realm. Especially in a region of fuzzy historical boundaries such as Southasia, maps feed national chauvinism.

The map of Southasia has other peculiarities as well. The most distinctive aspect of the region is the protrusion of peninsular India, so that when you see Southasia you tend to see the outline of ‘India’. The parts of the seashore defined by Pakistan’s Makran coast westward from Karachi and the Sundarban delta of Bangladesh are non-descript by comparison.

For decades, the hands of cartographers have trembled as they traced the outer boundaries of historical Jammu and Kashmir, for fear of the disfiguring rubber stamp of some disdainful bureaucrat’s assistant declaring, ‘The boundaries as depicted in this map are neither correct nor authentic, by order of the Home Ministry of Blah’.

Our maps segregate not only the natural landscape (the Thar on that side and Thar on this side, Sundarban on that side and Sundarban on this) but more significantly the communities on the ground. The Sindhi speaker is separated from Sindhi speaker and the Bangla from Bangla.

The Muslim is cut off from Muslim, the Vajrayana Buddhist from Vajrayana Buddhist. The fuzzy boundary that is the defining feature of Southasia since Gandharan times is anathema to the cartographers’ craft, which demands sharp lines in a region where all that history offers is a grey zone where the societies meet in a penumbra.

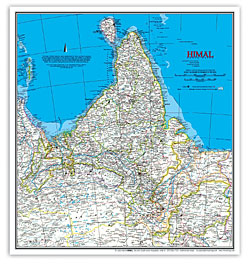

Himal Southasian, the bimonthly regional magazine which seeks to be occasionally irreverent, some years ago commissioned a map that would turn our assumptions downside-up. Artist Subhas Rai rotated the existing projections by 180 degrees so Sri Lanka came out on top and the Himalaya underside. Rai spent three months meticulously working on the project, for it had to be accurate in all aspects, including place names, topographical features, transport networks and boundaries. (Download: www.himalmag.com/images/map_poster.jpg)

When the map went out, the instinctive reaction was for everyone to unfold it the usual way and stare at the upsidedown place names. Open-minded teachers of geography and political science used it to shake up students’ worldviews. But the more common reaction was negative, as if the interpretation had dared challenge an article of faith.

AJNU professor of international relations, no less, confronted one of the map’s perpetrators, demanding, “Why have you turned India upside down?!” Reply: “Arreh madamji, dekhiye all of Southasia is upside down, not just your India.” At the Delhi Book Fair, in what were the days of post-Kargil ultra-nationalistic fervour, the map was perceived as a slight to the Bharatiya nation. The bookstall attendants felt intimidated enough by the public reaction to pull the offering from the racks.

Unlike the indigenous Delhi-wallah, the South Indian visitor to the book fair was more inclined to accept the map, for putting the peninsula on top. But it was the Sri Lankans who were most pleased, happy to be heading the heap rather than trailing the edge of the Subcontinent. Residents of the town of Matara at the tip of the island’s convexity welcomed a projection that put them at the uppermost tip.

Delhi’s denizens, so used to being in the centre of things, decided that the ‘right-side-up’ representation relegated them to the netherworld. The fact that even here the Indian peninsula remains the dominant feature seemed not to wash with this north-Indian audience. The Madras journalist who saw the map for the first time, on the other hand, had a gleam in his eye.

All in all, the map has served to shake viewers’ moorings just enough for them to begin to think about another world, another Southasia. If upside-down can be right-side-up, then as Faiz Ahmed Faiz said, perhaps the day will dawn when the downtrodden will rule the territories. Or words to that effect.