From Himal Southasian, Volume 19, Number 4 (JUL 2006)

Nepal’s Maoist rebels are headed towards becoming a part of the political mainstream, but they’re not there yet. It might just happen if they show some respect for the power of peaceful change.

Following the success of the People’s Movement and collapse of the Gyanendra autocracy in late April, a delicate experiment is underway in Nepal. An attempt is being made to draw a violent insurgency into open politics. Far-reaching changes have been initiated over the past two months to put the country on the track of full democracy and peace, and the process of integrating the Maoists into the mainstream has begun with their emergence on the stage of open politics. To what extent will they change the terrain of Nepal’s polity, and how much will they themselves will be transformed in the engagement with open society?

A jittery international community, India among them, feels that a fast-talking rebel leadership of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) is extracting excessive concessions from the political parties without submitting to an immediate process of ‘management of arms’, a route towards the demobilisation of Maoist fighters. While a section of civil society could not be more pleased with the inroads made by the Maoists into the national sphere, the political party rank-and-file wants disarmament to proceed immediately so that they can return and revive politics in the districts. They also fear a chasm between what the Maoists leaders say from the national pulpit and their ability to deliver a transformed cadre at the ground level.

The assumption is that the Maoist leadership is indeed committed to multiparty politics, which ipso facto carries with it the need for them to begin the process of laying down arms. To what extent can the rebel supremo Pushpa Kamal Dahal push the agenda, given that the political leaders have acted with sagacity in meeting him halfway?

As things stand, all over the country, the rebel combatants retain control of their weapons even as their people’s war has been abandoned. And therein lies the most critical challenge facing the Maoist leadership – of keeping the flock together so that when the time comes, the guns are laid out for inspection by United Nations decommissioning experts in a process leading to ultimate demobilisation. This is a hiatus, dangerous but also full of possibilities.

The valley summit

The pace of events since the April uprising has been quite astounding, with the reinstated House of Representatives stripping the monarchy of all power by a proclamation on 18 May and undoing much of Gyanendra’s autocratic transgressions since October 2002. For their part, the Maoists staged a massive rally in Kathmandu on 2 June, and intensified their demand for the disbanding of a Parliament that was undercutting their plank with its many progressive pronouncements.

An ailing Girija Prasad Koirala went to New Delhi, was graciously treated by his hosts, and returned to Kathmandu with a NPR 15 billion (USD 218 million) package for shoring up the interim government’s budget and kick-starting development. In a significant departure, New Delhi also indicated its willingness to allow UN experts to oversee the demobilisation process. The possibility of credible oversight generated momentum for the peace dialogue.

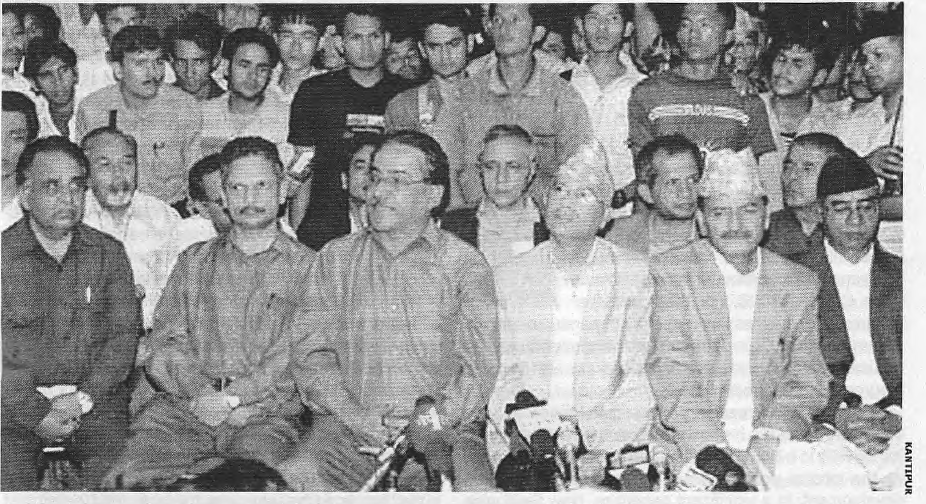

While the bilateral ceasefire continued to hold, official talks began between three senior Maoist leaders and three ministers representing different political parties. This culminated in a ‘summit’ organised at Prime Minister Koirala’s residence on 17 June. Dahal’s meeting with the prime minister soon expanded to include other members of the Seven Party Alliance (SPA) that had fought to bring down the royal autocracy with the assistance of the Maoists. After a quarter-century underground, Dahal suddenly became ‘public’ on the national stage for the first time, in a crowded and impromptu night-time press conference (see picture).

During the meeting, even as the ailing Koirala kept retiring to his room to rest his weakened lungs, what emerged was a far-reaching eight-point understanding, under which the two sides agreed to draft an interim Constitution, create an interim government including the Maoist, announce the date for elections to a constituent assembly, and dissolve the House of Representatives “after making an alternative arrangement”. For their part, the Maoists promised to dissolve their ‘people’s governments’ in various parts.

These rapid developments were propelled by the Maoist need to arrive at a ‘safe landing’ as quickly as possible, before there was a dissipation of their forces and energy. Even as the rebels appeared satisfied at what they had been able to extract at the talks, the political party rank-and-file were agitated at the equation of the Parliament with the Maoist people’s governments, and the silence regarding the decommissioning of rebel arms. “That was supposed to be the quid quo pro, not this,” said one minister, fuming. The leaders of all parties were left hoping that Dahal had given secret assurances on downing his guns to Koirala in their one-on-one session, for he certainly could not have said so in the larger group. Koirala, meanwhile, was not telling, and soon flew to Bangkok for treatment.

There were misgivings within the larger SPA that a coterie group within the Nepali Congress had essentially presented them with a fait accompli, and that the populist pressures based on the overwhelming desire for peace meant everyone kept his own counsel on the crucial day. The grumblings began the day after, with party workers castigating their leaders for giving in, stating that the Maoists had held on to their main card, which was the gun in their hands. At the same time, the rebels had the terrorist tag removed, received an agreement to enter the interim government, had their jailed cadre released, and, most importantly, got the announcement on the disbanding of Parliament. The naysayers maintain that Maoist sincerity has not been tested on the ground, even while the rebel bluster tries to push their position as the ‘mainstream’ position.

But it is also a fact that it is impossible to negotiate by committee, and the delicate situation of the Maoist leadership vis-à-vis their cadre required a level of secrecy and a need to maintain momentum. And while so many bemoan the lack of quid pro quo from the Maoist side, the very fact that the insurgents have abandoned their agenda of violent war can be considered their major concession, which was provided last autumn and which contributed to the momentum of the People’s Movement. But while it is important not to lose momentum, the negotiators on the two sides must realise that a situation must not be created where a dangerous rejectionism overtakes the parties.

What is left hanging in the air in the third week of June is how the Maoists are to join the interim government without the arms issue being settled. At the time of this writing, no letter has been sent to the United Nations on arms management. Meanwhile, amidst all this, Secretary General Kofi Annan has inexplicably assigned Ian Martin, the high-profile UN human rights official assigned to Nepal and expected to play a key role in demobilisation, to a six-week fire-fighting mission in East Timor. Nepal needed more consideration than that.

Managing the arms

Without doubt, the CPN (Maoist) high command has taken an extreme risk in the bid to reorient its political strategy, both in terms of personal safety and protecting the gains of the ‘revolution’. This has stemmed from its willingness to submit to geopolitical reality, as well as the dawning realisation that state power cannot be attained militarily. For this reason, and their evident willingness to finally abandon arms, the political parties have created space for them in the national mainstream.

Yet, there is no need to be placatory beyond a point, for the rebels did unleash a violent agenda on the people of Nepal. Moreover, their claim to speak for the Nepali people will only be tested once they go in for elections and the people get to vote freely, without the looming threat of the gun. The Maoist cadres need to undergo a rapid process of ‘politicisation’ so that they learn to function in open society, without resorting to the threat of the pointed muzzle. The parties must be allowed to penetrate the districts beyond the headquarters, which they still are unable to do due to the recalcitrance of the ground-level rebel activists.

In this context, the big question today is how credible is the Maoist willingness to submit to ‘arms management’, and what is the exact procedure? And if commitment is shown to be lacking, can the political parties hold off on the disbanding of Parliament? The Maoists need to understand that other than their own fighters, militia and cadre – their numbers yet to be ascertained – each and every other Nepali citizen wants those rifles and pistols to be handed in.

The entire disarmament exercise was labelled ‘management of arms’ in the 12-point agreement signed between the Maoists and the SPA last November, the roundabout language used to allow the rebel leadership to ‘sell’ the idea gradually to its fighters. In private conversation, some Maoist commanders have conceded to the political leaders that they could not survive within the organisation just yet if they went around talking of demobilisation and decommissioning.

Over the course of a decade, young fighters have been socialised into the culture of violence, and for them a decommissioning process would entail loss of prestige, power – and even income. Midlevel Maoist commanders have assured some interlocutors that while they would be willing to be confined in barracks, with guns available for inspection to the UN, they cannot give up arms completely because they do not trust the top brass of the Nepal Army. The reluctance of fighters and militia members to hand over their rifles may also be for fear of spontaneous reprisals by villagers who have remained sullen and subdued for much too long. If this is the case, then the Kathmandu government must create the conditions where such impromptu vigilantism is nipped in the bud.

There is no doubt that disarmament of Maoist fighters is key to Nepal’s future, even as every effort is made to keep the Nepal Army under a tight leash and made incapable of further crushing democracy or fighting a ‘dirty war’. The question is whether the leaders who today head an armed group should show due humility towards political activists who do not hold guns – given also the success of the peaceful People’s Movement, which had non-violent Maoist participation. Should a party that wants to submit to multiparty politics push its agenda in the districts through the sheer potential of armed intimidation? Furthermore, it is crucial to understand that truly free and fair elections to the constituent assembly will not be possible until the voting public knows that the rebels will return to the villages after the elections only as non-combatant sons and daughters.

Representative House

While to some the eight-point agreement of 17 June has the flavour of excessive concessions, the ambiguities may have been left there deliberately to provide ‘space’ for the rebels. It could also be that Dahal and his lieutenant, Baburam Bhattarai, have been talking in confidence not only to Koirala, but also to Indian interlocutors and senior UN officials, and that they may have provided believable assurances about their transformation for peace. While many believe that the return for disbanding the House should have been a definitive announcement regarding the renunciation of violence, it might just be impossible for the rebels to do so at this stage even if the intention is there.

As far as the Parliament is concerned, it is a fact that the stability of the state following the People’s Movement was possible only because the House was reinstated. Similarly, international recognition of the landmark legislative events that followed only took place because it was done by the House. Against such a background, what is the ‘alternative arrangement’ that could stand in for the revived Parliament of elected representatives, and would such an entity ever get the same legitimacy in the eyes of the people and the world? If there is to be a compromise body, would it not receive full credibility only when it is anointed by the House before it disbands?

Without the legitimacy granted by such a process, how can the donor community and foreign governments be expected to come forward to the assistance of an incongruous coalition government of political parties and Maoists who have not yet renounced violence? Will there, then, be an entity within the government of Nepal that actually commands two armed forces; the Nepal Army and the ‘People’s Army’? But there is also the argument that accepting the Maoists into the government is exactly the way to ‘co-opt’ them and force them to take the guns from their combatants. The argument is that such contradictions and ambiguities are the very elements that will allow the Maoist leadership the manoeuvrability needed to extricate itself from a difficult spot vis-à-vis their radicalised cadre and fighters.

Functional haziness

Two matters will thus be at the centre of the energetic debate in Kathmandu in the weeks ahead – what do the Maoists understand by hatiyaar byabasthapan (management of arms), and what will be the shape of the “alternative arrangement” that is to follow a disbanding of the House of Representatives? The creativity and forbearance with which the Maoists and the political leaders seek these answers will ensure whether Nepal will succeed in what so many have failed to do elsewhere in the world – bringing an insurgency to a decisive end so as to make up for lost time on the path to social and economic transformation.

The hazy ambiguity can be seen as necessary to bring the Maoists in from the cold, as long as there is careful monitoring of the process. But it must be said that the true transformation of Nepali society will not come from the CPN (Maoist), which would become part of the social revolution that is still required only after it joins the mainstream, multiparty politics. Such a social revolution must emerge from the clearly expressed desires of the Nepali public by way of the People’s Movement, for a non-violent society where historical ills are tackled through discourse and political evolution rather than through atavistic violence.

The Nepali people are convinced – if the insurgent and political leaders are not – that social and economic advancement will be achieved only through a return to peace, disarmament, reconstruction of the economy, and rehabilitation of the national psyche. The ‘inclusive’ Nepal of the future will come from a pluralistic state with social-democratic political leadership. The Maoists will also be part of this campaign, as a political party, once their fighters have been truly demobilised, in the process that begins with the ‘management of arms’.

The Maoists began their insurgency against a democratic dispensation back in 1996, with the Gyanendra interlude making it a convenient conversion for them to fight a dictatorial monarchy. Now that the kingship has been defanged, its future to be decided by the citizenry through a constituent assembly, will the rebels revert to their old violent agenda or will they adjust to the new reality? Over the past two years, after all, much has changed, even in their own strategy and thinking. With the CPN (Maoist) having taken a strategic decision to come to multiparty politics, the political parties open-heartedly decided to make space for them in the political spectrum. Will the rebel leadership now show their own magnanimity – and courage – by lowering their pitch and restraining their demands? Amidst the haze, and even taking into account the contradictions in pronouncements by the Maoists of Nepal, the outlook looks bright.