From Nepali Times, ISSUE #538 (28 January 2011 – 03 February 2011)

Kanak Mani Dixit in Nagarik, 22 January

It was just past 1pm on 16 January 2002. Muktinath Adhikari was teaching science to Grade 9 students at the Pandini Sanskrit Secondary School in Duradanda of Lamjung district.

Himal, Machapuchre and the Annapurnas, all standing witness to murders no one wants to talk about because of terror and confusion. But the mountains won’t let us forget what happened.

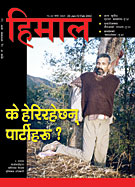

The war was at its peak in 2002, there were targeted killings, beheadings, torture. Horrific photographs of maimed victims and mutilated corpses were passed around, but they were too gory to be printed in the media. The photograph of Muktinath Adhikari’s body tied to a tree in which he is seemingly asleep was printed on the cover of Himal Khabarpatrika two weeks after his death. Even though there is no blood visible, the photograph shocked the nation and exposed the Maoist policy of executing civilians.

Nine years later, there is still fear in these mountains of central Nepal. In the absence of transitional justice, the fragility of the peace process and the apathy of the intellectuals in the capital, the villagers don’t dare speak out. Everyone knows who killed Muktinath Adhikari, but no one dares to come forward to lodge a complaint. The anniversary of Muktinath Sir’s murder used to be marked in a small classroom in Kathmandu’s Padma Kanya College, attended only by relatives and friends. It has taken nine years for the anniversary to be marked in Duradanda itself.

At the ceremony, Muktinath Sir’s friend, Thakur Prasad Tiwari got up to speak, but couldn’t continue. He sat down again, weeping inconsolably. Nearby, Muktinath Adhkiari’s wife, Indira, wiped away tears with her shawl. A few months before he was killed, Muktinath Sir had refused to pay a part of his Dasain bonus to the Maoists, saying: “I won’t give you money to buy bullets.” This expression of defiance and independence was unacceptable to the local commissar. Throughout Lamjung there were similar executions of teachers, social workers and ordinary citizens: Kedar Ghimire was killed just three days after Muktinath, Arjun Ghimire had nails hammered into his ankle and was told to walk. When he couldn’t, he was killed. Both are said to have been killed by the Maoist unit t

hat murdered Muktinath Sir. Also killed were health worker Chin Bahadur Thapa, Mohan Singh Ghimire, Nanda Jung Gurung, Tilak Raj Pandey, trader Mohan Lal Shrestha was bludgeoned to death because the Maoists said they wanted to save a bullet. Teachers Srikrishna Ghimire and Rishi Ram Koirala and Shanti Bohara all had their limbs crushed.

Mao Zedong was against torturing civilians. India’s Naxalites did not do targeted killings. Only Nepal’s Maoist leadership used the execution of civilians to spread terror and extend control. In an interview with the BBC Nepali Service in 2006 Pushpa Kamal Dahal said his instruction to his cadre was to “eliminate without torture”. He repeated this at a meeting with senior editors in Shanker Hotel that year, saying he laid down the rule that executions should be “with a bullet to the temple”.

After viewing a photo exhibition in Gorkha in 2008 that contained the picture of Muktinath Adhikari, Baburam Bhattarai wrote in the guest book: ‘Violence has a political and class character. To forget this and to analyse violence from an apolitical or non-class standpoint is not useful.’

There will come a day when the orphans of Nepal’s war will ask Bhattarai: “How was the murder of Muktinath Adhikari class-based or political?’ Only Muktinath Adhikari’s family members have the right to forgive his murderers.

The Maoist victims of state violence will also not get justice if the process required to bring Muktinath Sir’s murders to the court is not pursued.

It is unlikely that the Maoists will allow a genuine Truth and Reconciliation Commission to be put in place, hence the importance of keeping the door of the courts open for the legal investigative procedures. Unfortunately, recent Supreme Court decision seems to have been locked for legal recourse for the victims of state and Maoist violence, including the cases of Maina Sunar, Bardiya, Bhairabnath, Kajol Khatun, Diramba, Arjuna Lama and Maadi.

Back in Lamjung, Ekraj BK who was killed by the security forces and the disappearance of his two Maoist colleagues are cases which will also not see justice if the courts are disallowed their roles in pursuing excess committed during the conflict.