From Himal Southasian, Volume 23, Number 1 (JAN 2010)

It is okay if some people find Mount Kailash just a very interesting mountain, because it is certainly that. But to many, it is much more. This massif with a base of stark black granite and a sedimentary top, is overlaid with a cap of snow, history, myth, illusion and spirituality. With a technical interest in parallax and perspectives in relation to mountain flanks, I have for some reason long believed that Kailash is the one mountain – ‘himal’ – which looked more or less the same from all sides. This was clearly not true, but that is what I thought.

Without doubt, I had to go on a circumambulation – kora orparikrama – to confirm this personal presumption, but somehow never managed to over the years. Even though it has become easier to make this loftiest of pilgrimages, due to the internal combustion engine, helicopter rotors, and the roads and bridges that take one very close.

I recently found the opportunity to do a vicarious kora, through the medium of Deb Mukharji’s just published work, Kailash and Manasarovar: Visions of the Infinite (Nepalaya, 2009). And, Jai bam bhole! was I wrong. You could have told me that the massif of Kang Rinpoche (Ti se for the Bon) has distinct six facets that become visible during the circumambulation. I now know.

The author and photographer is a retired Indian diplomat and ambassador to Nepal in his last posting. This citizen from New Delhi has produced a fine tribute to a mountain in Tibet, under the aegis of a Kathmandu-based publisher – a thoroughly Southasian venture. Over three decades, Mukharji nurtured his interest on Kailash and the nearby Raksas and Manas lakes, taking inspiration and perspective from the Bon, Buddhist, Hindu, Jain and Tantrik traditions.

Kailash is at the interface of myth and geography. This is where many of the concepts of Southasia’s religions converge, the site of the Samudra Manthan, when the god and demons churned the ocean to obtain the nectar of immortality. Standing apart and a bit north from the Himalayan chain, the massif rears up at a point above what geologists know as the Tsangpo Suture, the line where the Indian plate that sailed away from Gondwanaland collided with the Asian Plate 45 million years ago.

How was it that a massif that stands back from the main Himalaya became such a centre for inspiration for the ancient Subcontinentals hundreds of miles of tortuous terrain away? In conversation, author Mukharji suggested that they would have known that this mountain is the epicentre for the headwaters of the great rivers of Southasia – the Indus, Sutlej, Karnali and Brahmaputra. The source of sustenance in the plains went in a straight line back to Kailash, and so made it the repository for all existential narratives, ‘peopled’, if you will, by a diverse pantheon from Shiva and Demchhok to Ravana, Padmasambhava and Rshavadeva, the first Tirthankar.

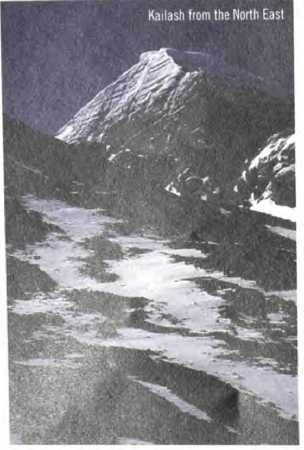

Kailash is one mountain you can talk about without having been there, and so I will. The Himalayan peaks, even when they are protrusions in the shape of a Dhaulagiri or a Shivling, are part of a range and so have a difficulty standing out and alone. Also for this reason, Kailash is a mountain of which you can do a definitive circumambulation the way you would a temple or chorten. The pyramid shape is one that endears itself to spiritual seekers looking to the skies, and here is a natural ziggurat, complete with steps heavenwards in the form of rock strata as seen from the south and west.

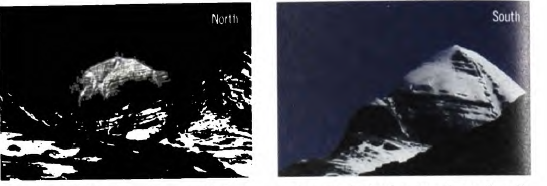

There are Tibetan massifs such as the Gurla Mandhata just across the Manas lake to the south, or Shisha Pangma some ways to the east, which do stand apart from the main Himalaya, but they are broadbased and without Kailash’s stand-alone distinctiveness. The six facets that Mukharji speaks of have their own attractions, especially the contrast between the gentle snowy dome as visible from the southeast, and the rearing cobra that makes up the sheer north face.

A new air route has been established for all international flights from Kathmandu going westward, and now aircraft overfly Dhangadi on the western tip of Nepal rather than heading southwest to Lucknow. This means that the Himalaya and the Tibetan plateau will remain closed the entire length of Nepal. On my next flight out, I peer over the Nepal and Kumaon ranges, to see if Kang Rinpoche is visible. That would be at least as good as the armchair kora I have just completed.