From Himal Southasian, Volume 18, Number 5 (MAR-APR 2006)

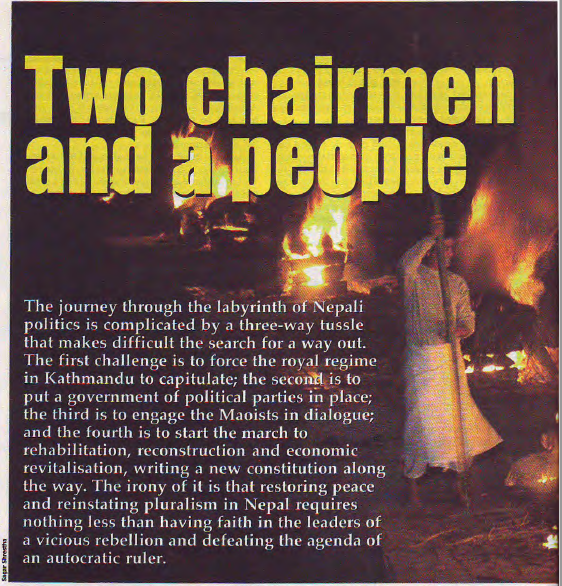

The journey through the labyrinth of Nepali politics is complicated by a three-way tussle that makes difficult the search for a way out. The first challenge is to force the royal regime in Kathmandu to capitulate; the second is to put a government of political parties in place; the third is to engage the Maoists in dialogue; and the fourth is to start the march to rehabilitation, reconstruction and economic revitalisation, writing a new constitution along the way. The irony of it is that restoring peace and reinstating pluralism in Nepal requires nothing less than having faith in the leaders of a vicious rebellion and defeating the agenda of an autocratic ruler.

It has not rained in Nepal for five months and the ground this spring is parched, the haze thicker for the dryness all around. Electricity production is so low that even the privileged of Kathmandu Valley are seeing 17 hours of load-shedding per week, and this has also affected drinking water distribution. The tourists have disappeared with the Maoist blockades and government curfews, and the five casinos of Kathmandu meant to trap them are filled instead with Nepalis betting their fortunes. Petroleum prices are suddenly up, and double-digit inflation is on its way. The political confusion on several fronts, however, is as yet preventing the accumulated frustrations from boiling over in a rash of spontaneous violence.

Everywhere in Nepal today there is listlessness, a waiting for something to happen. Potholes are not repaired, nor are buildings painted; and in the districts, the people have nearly forgotten the ubiquitous term of four decades’ standing, ‘development project’. There is a hope that the vortex of violence that has Nepal in its grip will be broken by the end of spring, before the monsoon sets in. Spring is historically the season of political change in Kathmandu, and something must give, or so people hope. That ‘give’ must come from the direction of the Narayanhiti royal palace, stuck in its militarist, undemocratic ways. As for the Maoist rebels in the jungle, they have already indicated in a variety of ways their desire – indeed their desperation – for a way to open, aboveground politics.

The polity is today at a stalemate awaiting release, either planned or forced, so that the 26 million people of this sizeable country can once again breathe the air of peace and freedom. That peace was wrested by the violence of the Maoist insurgency of ten years’ standing, and the state security’s response that has placed the country towards the top of the charts in numbers of tortured and ‘disappeared’. The freedom was first stolen in the villages by the gun-toting rebels, who even today like to claim they have public support; and in the last three years by a newly crowned king-turned-despot, who shows contempt for the people at every turn and speaks in Orwellian doublespeak of democracy and constitutionalism while proceeding to demolish both.

Both of the chairmen – the Maoists’ Pushpa Kamal Dahal and the royalty of Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev – hold the belief that the Nepali public is a peasantry more than willing to submit to their individual feudal dictates. They do not seem to recognise, or care to concede, that the citizens have developed a taste for democracy, and for what a modern-day pluralistic state can deliver in social and economic progress. They know that that future lies neither with king nor rebel – not in right-wing dictatorship, nor with ultra-left totalitarianism.

Over the autumn and winter, the insurgents have given ample indication of their desire to submit to the people’s will. The Maoists must perforce be tested in their announced willingness to join multiparty politics, but today it is the royal chairman who is the stumbling block to peace and democracy: by not responding to the Maoist ceasefire of four months’ standing last autumn, by continuing to snub the very parliament-abiding political parties who could save his throne and his dynasty, and – the unkindest cut of all – by militarising the Nepali state.

The entire national superstructure is crumbling around Chairman Gyanendra, and yet there is no indication that he understands the gravity of the situation. The destruction of the state structure and economy over a single year leads to the inescapable conclusion that Chairman Gyanendra has neither the aptitude nor acumen to be a head of government, which he has been since he appointed himself chairman of the Council of Ministers following the royal coup d’etat of 1 February 2005. It could even be that, having got himself into a jam, the chairman’s arrogance does allow him to extricate himself. He has not reached for the lines that have been thrown to him in the past year.

The frustration with the head of government is exemplified by the anger of a soldier shouting into a phone at a public call booth in Nawalparasi District last month, after a devastating attack on an army convoy. Here is how he was overheard: “Sir, how many more of my boys have to die because of the arrogance (hath) of one man?!” There is disillusionment in the police force with a king who insists on moving about in army combat attire, and increasing disquiet among the army officer corps who are unable to pass the message up the ranks. The police these days surrender at the first instance of attack, and the soldiers are fatigued without having really taken on the rebels – socially isolated and without inspiring leadership. They might well have put up a good fight for the sake of the citizenry, but not for the ‘supreme commander-in-chief’.

the need for peace and democracy?

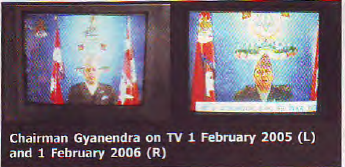

A time for sanctions

If the knot lies in the obduracy of Chairman Gyanendra, then the question would be how to force his hand. International condemnation has not worked for someone who seems willing to operate under the isolationist junta model perfected by the generals of Rangoon. Neither is the chairman bothered that his failures are paraded before the people, with fiascos in governance, diplomacy, development, economic management, administration and warfare. The public, finally, got a flavour of what some diplomats had known earlier about the royal ability to misrepresent, with the televised address on the anniversary of the takeover. Looking straight to the camera, on the morning of 1 February 2006, Chairman Gyanendra claimed that the Maobaadi were reduced to indulging in “isolated incidents of petty crime”, even while, at the moment of the taping, the guerrillas were destroying the Rana-era administrative centre of Palpa. He proposed that the national image and pride had been restored, when in fact the chairman cannot extract a single invitation for a state visit overseas, and foreign dignitaries shun the country like the bird flu. Chairman Gyanendra also, with a straight face, claimed that democracy had been strengthened during his year of royal rule.

Nor was that it. Having squandered numerous opportunities to build bridges to the political parties, in a Democracy Day message on 19 February, Chairman Gyanendra called on those “interested” parties to approach the royal person for discussions. He did this while scores of political leaders – including the topmost, such as Madhav Kumar Nepal of the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist) and Ram Chandra Poudel of the Nepali Congress – were in detention at his command. This was yet another exhibition of the chairman’s contempt for the Nepali public, by now too numerous to list. It is part-and-parcel of a mindset that thinks the international community will believe his democratic credentials if he repeats the term ‘democracy’ several times in a speech.

Given the recalcitrance of Chairman Gyanendra and his royalist cohort, and the unwillingness of the Royal Nepal Army (RNA) leadership to caution the chairman from this destructive path, the time has come for targeted international sanctions to check the anti-democratic, militarist royal agenda for the sake of the people of Nepal. As called for by several international human rights organisations, and increasingly by bold activists speaking out within Nepal, the sanctions would apply to the individuals of the royal regime – freezing the international bank accounts of members of the royal family including a nefarious son-in-law, and denial of visas for international travel by both that family and by the topmost handful of military generals and all the members of the royal Council of Ministers. The international community must also demand information from the RNA on officers implicated in violations of international humanitarian law, so that they can be prevented from going on the highly-regarded United Nations peacekeeping assignments. If the army does not supply those names to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, as it is currently refusing to do, then the individual battalions implicated must be refused peacekeeping stints.

It is important to go for targeted, individualised sanctions because the Narayanhiti regime does not respond – as even minimally democratic governments would – to the kind of sanctions that directly and indirectly hurt the people at large, such as reduced or cancelled foreign assistance to development projects and the government budget. A personal targeting and shaming, on the other hand, might yield results. It would spread immediate panic among the royalists ranks and serve as a potent ‘feudalist’ pressure on the chairman to back down.

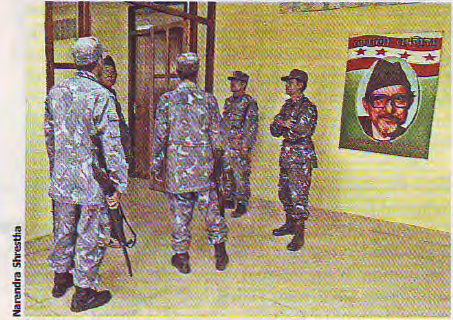

Chairman in fatigues

The deadlock of the moment is not of the Maobaadi’s making, but of Chairman Gyanendra’s, and an army brass that was a willing accessory to the coup d’etat. Narayanhiti has rapidly converted Nepal into a militarised state, where military officers have sidelined the civilian administrators and police throughout the 75 districts. Every one of Chairman Gyanendra’s actions over the past year of absolute rule must be overturned if Nepal is to return to a pluralistic state, including prejudicial appointments, illegal ordinances and numerous royal fiats. But most urgent is to undo the damage done to society by the politicisation and deployment of the RNA as de facto administrators. This illegitimate, unworkable diversion must be abandoned if social progress and economic advancement are to be guaranteed through an inclusive, democratic society. The people’s future must not be compromised because one man, who happened to get to sit on the throne at age 56, did not care enough for what ‘militarisation’ could do to society.

The RNA must return to its professional position as a national army rather than serve as the master-monarch’s bodyguard, and the professional officers who value their profession must make themselves heard by the generals currently locked in a feudal embrace with the royal palace. For now, the haughty generals have no humility to show for their force’s lack of fighting spirit since it was deployed four full years ago, even though the number of soldiers has nearly doubled in that period. Are they proud to be part of an army that refuses to go on the offensive, which today mostly guards only the barrack’s perimeter fence even as neighbouring police posts or district headquarters are razed to the ground? Can they take satisfaction in a force that carries out ‘air offensives’ by throwing mortars out of helicopter windows onto populated terrain? What will happen when human rights organisations investigate the reported large-scale executions at the Bhairabnath Battalion in downtown Kathmandu? And how is it that the officers guilty of the 2003 point-blank massacre of 19 people – 17 unarmed Maoist activists, and two innocent civilians – at Doramba village in Ramechhap District, during a ceasefire period, did not receive their deserved punishment?

8 February 2006

And how does one defend an army that has so little self-respect that, when challenged about human rights abuse, its topmost generals invariably reply, “Why do you not challenge the Maoists when they do the same thing?” This willingness to be judged at the same level as the renegade insurgents speaks of the quality of leadership with which the RNA is saddled – the same leadership that accepted Chairman Gyanendra’s call to arms, not to fight the Maoists in the jungles, but to battle politicians, lawyers, journalists and human rights activists.

The supreme commander-in-chief is bent on destroying the Maoists militarily, even though the RNA has shown itself incapable of going on the offensive, which had been the hope of many at the time of the royal takeover. There is also every reason to believe that Narayanhiti seeks a continuation of the conflict. It provides the chairman with the excuse to continue to rule, and to distort the political process in such a manner over the next year or two that he will have created an irreversible process through a sham parliamentary election – a constitutional coup on the shoulders of a military coup – that leaves him with a quantum of power he would be satisfied with, but which was not sanctioned for the constitutional monarch by the 1990 Constitution of Nepal.

It is difficult today to imagine Chairman Gyanendra reverting to being a ‘constitutional’ or ‘ceremonial’ king, so prejudiced are his views on pluralism and democracy, so public his contempt for the politicians and political parties, and so blatant and self-serving his agenda. It is not just the political activist that is reacting negatively – Narayanhiti would perhaps be taken aback by how the royalty has fallen in the public esteem. It is a surprise to find village elders scornful of Chairman Gyanendra, and the ability of the mainstream press to print ‘full frontal’ cartoons of the chairman is another indication of what has become acceptable. There is even a stirring of discontent palpable among Kathmandu Valley’s urban middle class, who has given Narayanhiti the benefit of the doubt for this long. The destruction of the monarchy’s image is not the Maoist’s doing, it is the chairman’s own.

And yet, it does not do to simply wish away monarchy in the arena of one’s mind. Responsible politicians are required to seek out ways in which to pressure Narayanhiti to backtrack, ‘because it is there’, and with an army backing it. They also need to consider that the Maoists are not disarmed, even if their call has suddenly turned syrupy. Indeed, the need of the hour in Nepal is to find ways to force the chairman-king to back down, and to take it from there if he does not. While there are things that the international community can do (condemning the royal takeover, suspending arms assistance and contemplating ‘smart sanctions’), the pressure on the palace must come from the Nepali people and their representatives – whatever it takes to get the palace with its back to the wall, and preferably in the form of an effective, well-organised, mass-based people’s movement. On the other hand, nobody need ever plan an anarchical revolution, after which it would be a question of picking up the pieces.

Even at this precarious and penultimate hour, it would be possible for Chairman Gyanendra to backtrack. He could still rescue his dynasty, if not his own rule, by surrendering to the public. This would happen through direct admission that sovereignty lies with the people and not in the crown, and in accordance with the Constitution of 1990. Following the royal climbdown, there must be guarantees of unquestioned control of the RNA by the civilian government; a rollback on all ordinances, orders and appointments of at least the last one year; an all-party government either by reinstatement of the Third Parliament (disbanded in 2002) or through an understanding among the political players; and the all-party government calling for a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution. This last is required to bring the Maoists in from the cold, given their process of reformation and given the past year’s proof of Chairman Gyanendra’s naked ambitions. Even to do away with the monarchy, the citizenry would have to be given a choice through a constituent assembly.

To believe or not to

And the Maoists do, very much, want to come in from the cold. The rebel change of heart is based on cool pragmatism or sheer desperation, depending on how you read it, but their recent pronouncements are credible enough to take them up on their offer. As the country is already at war, there is really nothing to lose in doing this. If the rebels are being manipulative and are found out, the state would simply be expected to return to war. To the plaintive question, “But can we believe the Maobaadi?” the answer is simple – there are reasons to believe that their resolve is genuine, and not because they are ‘nice’ people.

In August 2005, the Maoists held a plenum in their ‘home district’ of Rolpa and debated a resolution that was finally passed unanimously: the rebels would take a 180-degree turn (not announced as such), turn their ideology on its head, and enter ‘competitive multiparty politics’. This was the untying of the most important and troublesome knot, for in one stroke the Maoists put behind them the rhetoric and agenda of ‘people’s war’, on the basis of which, for ten long years, they have motivated their fighters and propagandised them on the takeover of Kathmandu Valley. There remains the challenge of how to tackle the rebels’ gun-in-hand, which no longer has even the sanction of a ‘people’s war’. The violent inertia among the Maobaadi must be allowed to dissipate without further violence, which is why responsible politicians, society leaders and foreign diplomats should promote an engagement with the rebels, rather than go into naïve or self-serving denial.

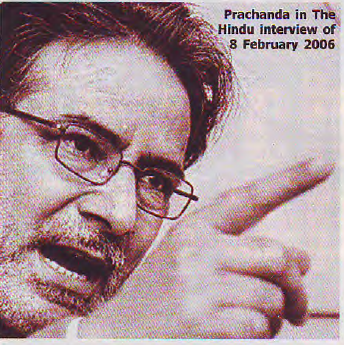

It was after the Maoist plenum, on the basis of their willingness to move towards non-violent politics and on the rebound from Chairman Gyanendra’s constant rebuffs, that the mainstream political parties decided to engage with the rebel chairman, Pushpa Kamal Dahal (‘Prachanda’). The leaders of the alliance of the seven parliamentary parties agitating against ‘royal regression’ flew to Delhi and met with Mr Dahal and his ideologue-in-chief, Baburam Bhattarai. They emerged on 22 November with a 12-point understanding, the goal of which was to challenge the royal move and prepare for a constituent assembly as a way to address the Maoist bottom line. In early February, the Maoist leadership suddenly unleashed their leader, Chairman Dahal, on the national and international media with unrehearsed on-camera interviews.

In the interviews, the Maoists supremo was playing to diverse national, Subcontinental and world audiences, as well as to his own cadre; and so, while disarming, his statements contained their share of contradictions. At times full of uncompromising bluster, at other times sounding conciliatory, Chairman Dahal sought to convince of the Maoist decision to come into multiparty politics, laying it out as a magnanimous act of great proletarian wisdom. The chairman presented several scenarios of possible resolutions on a ‘pick one’ basis; but most importantly, he conceded that the Maoists’ descent to ‘multiparty politics’ was dictated by the regional geopolitics, and the US and Indian support for the RNA that had made the fight difficult. The Maoist conclusion, he said, was that adjustments were required to Mao-Lenin’s 20th century communism for implementation in the 21st century. The Maoists of Nepal were the vanguard for this, from whom even the Indian Naxalites could take a lesson or two, he said, such as the importance of parliamentary politics!

Sitting in a New Delhi safe-house during the interviews the Maoist chieftain then proposed, with his chief ideologue and one-time rival Mr Bhattarai by his side, the specific ‘nikas’ or way out of the quagmire. He suggested that the Maoists should stay out of the fight for democracy in the beginning, recognising perhaps the domestic and international difficulties if armed rebels were part of a democratic movement. At one point, Chairman Dahal suggested that the most practical nikas is a revival of the Third Parliament. This reinstatement was not to be through royal initiative, but something to be wrested from Narayanhiti through an energetic movement that would unilaterally announce the revival. The Parliament would garner international recognition, and appoint an all-party government that would negotiate with the Maoists and pave the way for a constituent assembly.

At several points in the interviews, given to Nepali and Indian dailies and the BBC World Service radio, the Maoist chief even indicated his willingness to accept a ‘ceremonial’ kingship if the constituent assembly outcome so warranted. On the run-up to the assembly elections, the rebels would need international supervision of the RNA and the rebel fighters. This is seen by their leadership both as a means to protect the cadre in the process of weapons decommissioning, as well as a sop to prove ‘international recognition’. The greatest difficulty for the rebel commandants will be to convince battle-hardened fighters that the ten-year fight had been worth it. Besides the fact that Chairman Gyanendra will not hear of UN involvement, there is a problem in the Maoist projection here: all-powerful New Delhi too rejects the suggestion, for reasons of geopolitics quite different from the chairman’s.

How does one believe the Maobaadi leadership, given their history of manipulative manoeuvring? Would they not take the political parties for a ride? Fortunately, the credibility of the insurgents’ desire to jettison the ‘people’s war’ and enter the world of competitive parliamentary politics does not depend on the ‘Prachanda interviews’, which are but attempts to make the act of climbdown convincing to the Kathmandu middle class, the Indian intelligentsia, and the world at large – not to forget their own cadre, who are all listening in on their FM and short-wave receivers. There are several reasons why Mr Dahal and Mr Bhattarai are convincing on this one, this time around. To begin with, the change of policy was the result of a unanimous decision of the rebels’ expanded central committee meeting – called a plenum – which makes this reversal more than what is contained in polemical press releases that get faxed and emailed to Kathmandu. The fact that Chairman Dahal was openly on television and allowed himself to be photographed for the press indicates a desire to end underground life at age 52. Also significant is the fact that the chairman was committing himself before the Indian government and public opinion, which would have New Delhi breathing down his neck if there were to be a blatant backtracking.

Non-Maoist Maoists

Why did the August plenum take the decision it did? Obviously the Maoists had grown too big too quickly and were having to make adjustments to save their ‘revolution’ from internal corruption, this last being something Chairman Dahal has admitted. Having gotten to within fighting reach of political power-sharing in Kathmandu – which was never, perhaps, really expected – the leadership realised the need for a change in strategy. This is because no government in the world, including India’s, would recognise Maoists as ‘Maoists’ in the seat of power in Kathmandu. There was only one way out: renounce the ‘people’s war’ even if one did not say it out loud, and put your best face forward.

The violent politics of the Maobaadi had properly incensed the international community, and the post-9/11 ‘war on terror’ was a set-back for a group that has used terrorist methods. American, British and Indian assistance began to flow in large volume to the RNA, and was suspended only as a result of Chairman Gyanendra’s coup. But it was when India began to sense a danger to its own internal security from copycat insurgencies in its hinterland – due to the high-profile Nepali Maobaadi – that the ground shifted for the insurgents. It did not help that, during their rise and spread, the Maoists had made liberal use of anti-Indian rhetoric, based on an ultra-nationalist ideology actually devised by Gyanendra’s father, Mahendra, back in the Panchayat era.

The Maoist vitriol against India, the bans on Indian vehicles and cinema, the targeting of Indian multinational property in the Nepal Tarai, and in the last instance, the whimsical preparation for an Indian attack through a campaign of digging trenches all over – none of this endeared the Maobaadi to the Indian state. When India decided it had had enough – and its foreign minister had termed them ‘terrorist’ even before Kathmandu did – it deployed its SSB paramilitary force along the open Nepal-India border to monitor movement. It nabbed two central Maoist leaders in Madras and Guwahati and set them on trial, and it prevented wounded Maoist fighters from being treated in nursing homes in towns like Luck-now or Gorakhpur. Proactive Indian displeasure, as well as the realisation that New Delhi would never ‘allow’ a Maoist government in place in Kathmandu, have been possibly the most important factors for the rebels to want to come aboveground – it is a requirement of their very success that they abandon the ‘people’s war’ that has brought them thus far. In addition, the role of the Indian left parties, particularly the Communist Party of India (Marxist), seems to have been important in influencing the Nepali Maoists to see sense.

No less important, perhaps, is the domestic challenge faced by the Maoists. Here, too, the rebels realised that they could spread thus far and no further in their goal of state takeover. While they have been able to make spectacular hit-and-run attacks in the hinterland, they never came close to taking over any of the 75 district headquarters, let alone Kathmandu Valley. The militia and guerrillas were thus confronted with the prospects of a never-ending fight, whereas joining aboveground politics would require laying down the gun and joining multiparty politics. In the early years, the rebels were able to motivate fighters with their run of assaults on police and army posts, and the promise of the prize of Kathmandu. Successful mass attacks on barracks and the looting of weapons also served to keep up morale. As the army acquired Belgian Minimi belt-driven guns, as well as more-efficient American M-16s in place of aging India-donated SLR rifles, and with the RNA learning to defend its barracks with mines and concertina wire, the insurgents had to turn to the ‘lowly’ task of destroying administrative offices, government infrastructure and poorly-armed police chowkis.

With the army refusing to engage them in the field, the Maoists could not hope for firefights and battles to show their fighting mettle. All in all, for the last few years the rebel fighters have been reduced to clandestine ambushes of security forces, laying down improvised explosive devices on public roads, as well as blockades and highway closures. Even as it was getting harder to motivate the cadre, the instances of banditry and wayward violence not sanctioned by the high command indicated disintegration of the fighting spirit. A sudden, deep and open ideological split between Chairman Dahal and Mr Bhattarai in the spring of 2005 divided the rank-and-file all the way down to the district level. It is not yet clear how that rift was patched up, but the leadership seems to have decided to seek a surakshit abataran (safe landing) while the movement was still united. The Maoists could continue to make the country ungovernable, and that was even easier with Chairman Gyanendra leading an unmotivated security force, but the goal of capturing Kathmandu was receding.

Due to domestic, regional and international considerations, therefore, the Maoist decision to come to a ‘safe landing’ is convincing to all players. All players, that is, other than some diehard members of Kathmandu’s royalist elite and the American ambassador, who in mid-February conducted a frenzy of meetings, speeches and letters-to-the-editor trying to convince whoever would listen of an impending Maoist takeover of Kathmandu, and of the need to reject the Maoist siren calls that the 12-point understanding and the Maoist interviews represented. Lacking a nuanced understanding of the fast-changing Nepali political discourse, and obviously running to the dictates of his own administration’s ‘fight against terror’, the ambassador managed – it is hoped momentarily – to deflect the debate and the search for peace. Whereas a civil cautionary note to alert the political class of the dangers of Maoist doubletalk would not have been untoward, the ambassador was acting very much the American cowboy in a Nepali china shop. As the royal regime’s detainee, civil-society leader Devendra Raj Pandey said from jail on a mobile phone, “The ambassador’s statements are designed to take the country back to civil war, more bloodshed, and away from a political solution.”

session.

Closure of the ‘people’s war’

If the Maobaadi are to be believed in their desire to bring the ‘people’s war’ to a close, then it is Chairman Gyanendra, leading the RNA by the nose-ring, who is the obstacle for a return to both peace and democracy. And so, once again the question: how to bring Narayanhiti to heel? Today the regime seems to stands tall, but its bones are brittle. The king has with him no supporters, other than the quislings and opportunists who have joined the cabinet and leaders of mini-parties who want to make good under royal patronage. His plan is to ride it out through the spring of 2006 in the hope that the monsoon will defuse the political agitation, and a year from now he can organise a sham parliamentary election to gain sham legitimacy. But this is a plan concocted in a royal vacuum, by a man who believes in his ability to stay in power with the help of a dispirited RNA. In the towns and villages, there are very few opinion-makers today who feel for the monarchy, and especially the current incumbent. Internationally, it is not likely that the players important to Nepal – India, the UK, China, Japan, the European Union, the UN Secretary General or the US (despite one odd plenipotentiary) – will come around to seeing things the way Chairman Gyanendra would like them to do.

But while the international community should stand ready to provide support in addition to what it has already done, peace and democracy are goals that Nepalis themselves must fight for. With the plethora of ‘donors’ willing to invest money in all kinds of conflict-resolution exercises, it will be the death of the ‘fight for freedom’ if the politicians too start accepting foreign assistance under the line-item ‘restoration of peace and democracy’. There is no doubt, however, of the need for the politicians to ratchet up the battle, and their lethargy thus far is no proof of the lack of urgency in the situation. It is just that the rage against the royal takeover has not been translated into effective mass action.

Obviously, the contradictions between the political parties, the power centralisation within the parties – particularly around the person of Girija Prasad Koirala of the Nepali Congress – and the copious lack of imagination and planning in the leadership ranks generally, have all been contributing factors to the inability to defeat the royal action more than a year after the takeover, even though the militarisation underway should have energised the political class. But it is also important to note that politicians better understand the challenges, particularly those who have held national office. This is something the firebrand members of civil society or impatient diplomats do not appreciate enough.

To take one example, the seniormost politicians are circumspect when it comes to the slogan for ‘democratic republic’, even though sections of civil society have already run with it. The goal of a democratic republic is not only compatible, but goes to the heart of the demand for a pluralistic state; but until recently, it was the battle cry of the Maoist rebels. Indeed, ‘democratic republic’ as a slogan to fight the royal agenda is compromised unless simultaneously the matter of the Maoist gun is addressed. The political parties have today come around to accepting the constituent assembly as the departure point for the post-Gyanendra evolution of Nepali democracy, and they did this only after the Maobaadi were able to convincingly project their about-turn on the ‘people’s war’. But they still hold arms, whereas the political parties never have.

It must be added that Chairman Gyanendra over the past few years has done more than the Maobaadi to destroy the image of monarchy, and likewise he has done more to give energy to ‘democratic republic’ than the rebels in the jungle. It has become difficult to conceive of the man with the crown functioning as a constitutional monarch, bound to a ceremonial throne, without residuary powers.

Building democratic steam

It is already very late in the day to wrest democracy back from the grip of Narayanhiti. And it is the political parties – assisted by various branches of civil society, including the bar, the journalists, academia, human rights activists and independent citizens – who must rise to the occasion. What are they to do? Why, they must build steam in the movement to force the regime against the wall, for the sake of democracy and for peace through dialogue with the Maobaadi.

But what to do if the chairman refuses to budge? Many political players are reduced to waiting for a spark, some accident, which would act to release all the public’s pent-up anger in a flood that would wash away the monarchy. But that would be to invite anarchy, which in this country can be savage, and the political actors as yet have no mechanism in place to manage such a destructive bout. A planned roadmap would have to be a mix of what is practical and desirable, given that the situation is complicated by the three-way tussle between the rebels, the royal regime and the political parties/civil society. The goal is a return to representative government, for which the rebels have to be brought into a safe landing, while the monarchy has at the very least to be constitutionally-neutered.

The great advance of the last half-year has been the convincing presentation of the Maoists that they do indeed want to come to a landing. The four-month-long ceasefire allowed the Maoists to recoup a large measure of their political capital, which had been lost in their heightened militarism of the past few years. The Maoists took back their ceasefire when it became difficult to sustain under the RNA’s ‘non-cooperation’, and now they have gone back to attacking state security and destroying government property, and have announced an onerous period of nationwide closures in the coming two months. The rebel leadership must have its compulsions, but they surely realise that their return to violence weakens the very political parties whose help they need to come aboveground. Their continuing violence strengthens no one but Narayanhiti and the RNA, and makes the already-sceptical international community nervous.

The Maobaadi must unilaterally call for a cessation of hostility and do their bit, even if the state security fails to respond as before. They must do this to allow politics to revive in a country where it has almost died, and to give peace a chance. Meanwhile, the political parties do not have a choice of building a people’s movement. At the moment, they are waiting for international pressure, the public shaming, and desires for continuity of dynasty to force Chairman Gyanendra to backtrack. His record thus far points against such a possibility. There is no alternative to an energetic political movement.

The mainstream political parties are united today on the political fight for a constituent assembly, which would also carry along those who seek a democratic republic. The constituent assembly is thus a widely recognised roadmap to peace in Nepal today – it has the intelligentsia and the political class united, the international community on board. Ironically, in one of his interviews, Chairman Dahal has even spelt out how this is to be done: as mentioned previously, this would be through the revival of the Third Parliament, followed by the formation of an all-party government, which would hold dialogue with the rebels and organise the elections for the assembly.

The brave new world that would suddenly unfold with the revival of Parliament – or another way in which an all-party government could be formed, if that were possible – is tantalising for anyone with some political imagination. The all-party government would start a dialogue with the Maoists. Simultaneously, the army would come under the Parliament and the all-party government of the day, for which the existing National Security Council, which ensures civilian control of the military, would be activated. The nature of the constituent assembly would have to be worked out.

This is how the ground has shifted in Nepal – before the August plenum, it would have been premature to propose the constituent assembly as the roadmap, because the Maoists were steadfast in their violence agenda and the ‘people’s war’. With the rebels having made a credible departure, the constituent assembly, as a means of giving the people their ultimate right to choose their system of government, suddenly comes onto the centre stage. This, then, would be the slogan with which to challenge Narayanhiti. Chairman Gyanendra is by now the only powerful player opposed to the constituent assembly, and he would certainly try and sabotage every move to restore democracy through a revived Parliament.

It would be a welcome thing if Parliament were to be revived through a Supreme Court verdict on a long-pending case, as some politicians seem to be hoping for, so they can be saved the trouble of organising a movement. It is even possible that the concerted show of national and international solidarity might shake the moorings of Narayanhiti, its cohort and the military leadership, forcing them to capitulate without further fight. That seems unlikely to happen, however. Besides, almost by definition, a democracy that has not been fought for is bound to have within it elements of anti-people compromise. There is no way around it: a people’s agitation is required to push back the autocratic agenda of Narayanhiti, supported by an international community willing to place individualised sanctions against the royalty, the military top brass and the ministers.

It is just possible that the Spring of 2006 will bring such a political tsunami of sheer people power. But it is also possible that the chairman-king will continue to bleed the people, making it into the monsoon period and getting himself a respite. If that happens, there are no alternatives but to continue the non-violent fight for peace and democracy – through the next monsoon, and the next and the next.

But the best will be if the Spring of 2006 yields a people’s movement that vanquishes Chairman Gyanendra, at which point Nepal can then start on the long-delayed process of reconstruction and rehabilitation – and the revival of a democracy better than that experienced between 1990 and 2002. There are too many young widows, too many orphans, too many displaced, too many young fighters in the land. The long haul will begin once Chairman Gyanendra’s agenda is defeated, and the Maoists are taken along on the march of peaceful, aboveground, multiparty parliamentary politics. The last time democracy was ushered in was the people’s movement in the Spring of 1990 – the Jana Andolan 2046, according to the Nepali calendar year. What the people await this spring is Jana Andolan 2062, not expecting the chairman-king to give up without a fight.