From Himal Southasian, Volume 23, Number 2 (FEB 2010)

Closed-circuit television clips now offer an unprecedented ringside view of blasts, blood and carnage, making voyeurs of us all. Often, the suicide bombers of the Southasian Northwest tend to blow themselves up in public spaces or secured spots that have CCTV cameras. Such video sentinels do little to prevent the carnage, but provide us with graphic real-time playback of the last tragic moments before the explosion.

In the clips taken during the 20 September 2008 Marriott Hotel blast in Islamabad, a truck is seen coming to a halt at the hotel’s gate. There is a small detonation, which results in a fire in the driver’s compartment. The hotel guards scatter then mill about in confusion, like faraway mannequins in the unmoving frame. One comes up with a fire extinguisher and gingerly starts spraying the cabin. Then the blast happens.

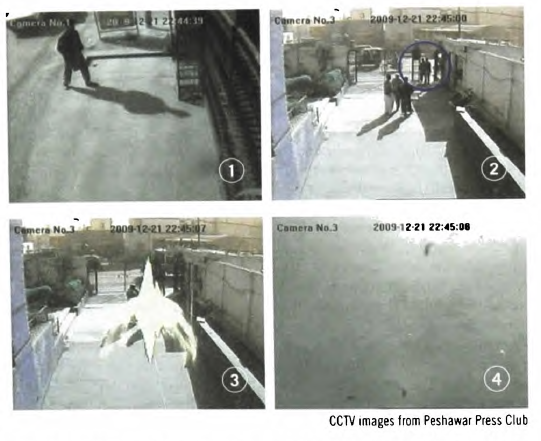

At the gates of the Peshawar Press Club, on 22 December 2009, three men are talking in the slanting winter sunshine. A man walks up to the gate, and Constable Riaz Uddin goes up to check him out. The on-screen clock turns to 22:45:09 (undoubtedly set wrong) as the detonation takes place, and flying dust immediately covers the screen. A side camera shows the wildly swinging gates after the blast, with no one left standing.

A week later, on 28 December, a CCTV camera looking down over the M A Jinnah Road in Karachi showed the Ashura procession – thousands walking calmly down the boulevard. The front row is about 100 across, full of assorted banners, some held aloft and others on the front. The mass reaches back as far as the unmoving camera’s eye can see. The procession approaches a traffic crossing. Suddenly, about fifty or so deep in the crowd, on the far side, a blast erupts. It rips through the crowd, the dazed procession survivors scatter, and a momentary mushroom cloud develops overhead.

Given such easily available CCTV footage, we are now provided with access to images of blasts that kill and maim. Most of the time, the camera dies with the explosion, so one rarely gets to see the blood and gore. Cameras mounted afar do often survive the blast, as in Karachi, but keep you away from the details of the carnage. The very nature of the footage tends to maintain a distance between the television viewer and victim – there is no zoom nor pan from the automated camera. All of that is left to the television reporters, who will arrive before long. Alongside, private television channels manage to get the publicly held CCTV footage to the public in no time, while the victims are still being rushed to hospital.

Just as warfare by remote-controlled drones has been introduced to the world through Northwest Southasia, so too has this new way of viewing carnage become specific (thus far) to the Subcontinent. At this point, one question arises in my mind: Is it appropriate to broadcast CCTV footage of bomb blasts, in the name of freedom of information? I think not, because it provides mass murderers a sense of gruesome fulfilment, and probably whets their appetite for more. It must indeed give the planners who engineer the death of innocents a macabre sense of achievement, as they send suicide bombers into the crowds. All they have to do is wait for the television channels to air the CCTV footage, and they are able to see the success of their project almost as soon as it is carried out.