From Himal Southasian, Volume 24, Number 1 (JAN 2011)

Hasan Mansur (Milon-da), the tourism entrepreneur of Bangladesh, has lovingly built a boat to the specifications of his own experience and his deltaic country. The M V Aboshar has 20 cabins with a wrap-around passage and a top-deck providing a common space for dining and viewing the scenery. And yes, Bangladesh has scenery to blow the mind. We set out from near Dhaka and were soon on the Meghna, which joins the larger Podha (Ganga), the latter itself having joined the Jamuna (Brahmaputra) earlier on. Unlike the upstream tributaries, which lose their identities to the mainstream, here in Bangladesh the larger river is subsumed within the smaller arrival.

As we proceed south on the Meghna, it becomes so wide that the far bank nearly dips beneath the horizon. We swing away to the west and slip into distributaries heading southwest, always in the company of flotillas of floating water hyacinth. There are many fishing boats, but the scene before our eyes is not one of a sea of sailboats, as the travel guides have prepared us for. Diesel engines, large and small, have taken over the delta.

As evening comes on, we pass dozens of huge ferries fetching up from Khulna, making the overnight run to Dhaka’s Buriganga terminal. Taking on more than three hundred passengers each, these ferries leave destablising waves in their wake, as they pass fishing dhows, jet boats and launches. The ferries use their dazzling searchlights to probe the darkness ahead and indicate the intended direction to oncoming boats.

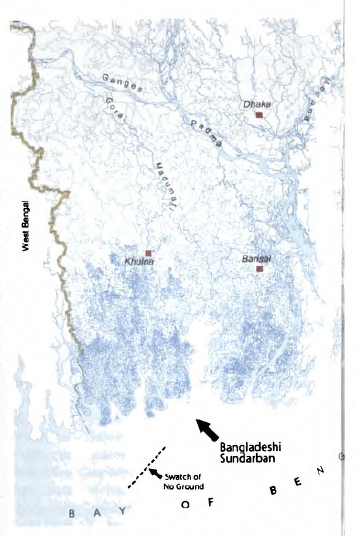

The Sundarban, or Shundorbon, can mean either ‘beautiful forest’ or ‘forest of the beautiful tree’ (the Shundor). Whichever of these interpretations one prefers, it remains a ravishing region indeed, a dense network of water capillaries spread over hundreds of square miles in deltaic Bangladesh and neighbouring West Bengal. The western part of Sundarban that lies within Bangladesh is the richest and most unspoilt, and that is where we are headed on the M V Aboshar. Satellite imagery clearly shows this large patch of green standing out in the midst of the all-pervading brown.

The land- and water-scape of the Sundarban is marked by canals which, due to the precision of their curves, look as if they have been planned by engineers. The forests come right up to the banks, and if you choose to walk it is through a sea of mangrove roots that rises up from the mud in search of air. The channels are host to crocodiles, and the forests to the Royal Bengal Tiger. It is a rare visitor, however, who will get a glimpse of either.

However, on the larger distributaries, you are likely to see another highly endangered species, the Ganga Freshwater Dolphin. Keep your eyes peeled and you will see a dolphin breaching the waves. Idling overnight in an inlet, Milon-da shows us a film made by his wildlife biologist son Rubaiyat Mansur ‘Mowgli’ about the dolphin species, known here as the Susuk. The species is found in all the tendrils and strands of the delta, and upstream all the way to the rivers of Assam and Nepal. The fish is blind because it has no need for sight in the muddy waters, and catches fish through the use of sonar.

Milon-da keeps us entertained in the evenings amidst the silence of the Sundarban, with water lapping on the sides of the boat and the moon reflecting all the way to the nearby shore. In fluent Nepali, he tells me how new islands have been born in the Sundarban over the two decades that he has been organising the water tours. Pointing aft at the woods, as the rising tide covers the forest floor, he says, ‘Twenty years ago it was a small chor (sandbank), a few years later it had grass, and now it is a mangrove jungle.’ His Nepali comes from many years as a guide taking tourists to Lumbini, Pokhara and Kathmandu.

Mud is what makes Bangladesh: fine clay hundreds of feet deep that has been brought downstream over geological time by the Ganga and Brahmaputra (or their predecessor watercourses). The creation of the delta continues day after day, and indeed what is most striking about the Sundarban is the mud. It wells up from the deep as you look down at the water. Pick up a fistful of mud on the bank, and you find it slippery, dark grey and oh-so-fine. With origins as far upstream as the Himalaya, it is carried by the currents, from where we idle, deep into the Bay of Bengal, where there is a massive mud canyon with the enchanting name whose origin one has got to investigate: ‘Swatch of No Ground’

As any freshwater dolphin of these parts would have told you, mud is indeed what makes Bangladesh. I did not see a tiger in Shunderbon, but I saw a lot of good mud.