The political partition of the Subcontinent in 1947 did not have to lead to economic partition, but that is ultimately what happened. This did not take place right away, and many had believed that the borders of India and Pakistan’s eastern and western flanks were demarcations that would allow for the movement of people and commerce. It was as late as the India-Pakistan war of 1965 that the veins and capillaries of trade were strangulated. In the east, in what was to become Bangladesh just a few years later, the river ferries and barges that connected Kolkata with the deltaic region, and as far up as Assam, were terminated. The metre-gauge railway lines now stopped at the frontier, and through-traffic of buses and trucks came to a halt. The latest act of separation was for India to put up an elaborate barbed-wire fence along much of the 4000 km border, a project that is nearly complete. Today, what mainly passes under these wires are Bangladeshi migrants seeking survival in the faraway metropolises of India – and contraband.

This half-century of distancing between what was previously one continuous region has resulted in incalculable loss of economic vitality, most of it hidden under nationalist bombast. Bangladesh lost a huge market and source of investment, even as the heretofore natural movement of people in search of livelihood suddenly came to be termed ‘illegal migration’. Bangladeshis were wounded by the unilateral construction of the Farakka Barrage on the Ganga/Padma, a mere 10 km upstream from the border, which deepened the anti-Indian insularity of Dhaka’s new nationalist establishment. Forced to chart its own course, Bangladesh concentrated on developing its own soil and society, uniquely building mega-NGOs such as Proshika, BRAC and Grameen, developing a healthy domestic industrial sector such as in garment manufacture, and learning to deal with disastrous floods and cyclones.

In India, the lack of contact and commerce led increasingly to an evaporation of empathy for Bangladesh, which became an alien state rather than a Bangla-speaking sister Southasian society. The opinion-makers of mainland India wilfully ignored the interests of the Indian Northeast, which they see as an appendage with no more than four percent of the national population. The seven states of the Northeast, meanwhile, became weakened economically with the denial of access to Bangladesh’s market and the proximate ports on the Bay of Bengal. Mainland India, of course, could easily afford to maintain its strategic and administrative control through the ‘chicken’s neck’ of the Siliguri corridor, but few considered the economic opportunities lost to the Northeast over five decades.

Distrust and xenophobia in Bangladesh, the imperial aloofness of New Delhi, and the Northeast’s lack of agency delivered a status quo in disequilibrium in the northeastern quadrant of Southasia that has lasted decades. Unexpectedly, there is a hint of change. A relatively little-remarked-upon memorandum between the prime ministers of Bangladesh and India holds out the possibility of erasing the anti-historical legacy of closed borders and rigid economies.

Tantalising promise

It was in January 2010 that Sheikh Hasina Wajed and Manmohan Singh signed the broad-ranging communiqué in New Delhi. As a marker of dramatically improved relations between Dhaka and New Delhi, the agreement includes the Bangladeshi promise to allow transit facilities to India through its territory, and India’s commitment to energise bilateral commerce by bringing down tariff and non-tariff barriers.

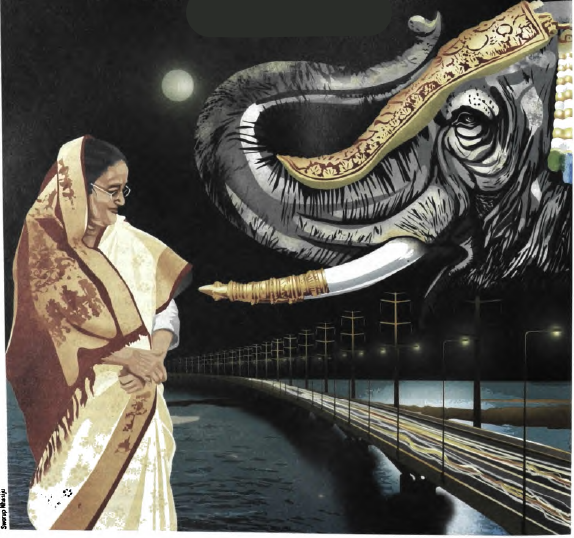

The economic opening promised by the memorandum would benefit Bangladeshi business and population, the Northeast as well as the other nearby states of India, from West Bengal to Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh. The Northeast – Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura – would finally develop separate economic linkages southwards. The agreement holds India to its promise of granting unrestricted access for Nepal and Bhutan to the Bangladesh ports. Into the future, one can envision Bangladesh serving as the natural bridge between Southasia and Southeast Asia. The grand and under-utilised ‘multipurpose bridge’ over the huge expanse of the Brahmaputra/Jamuna, inaugurated in 1998 with the hope of carrying international rail and road traffic, would finally see something more than provincial traffic.

The Hasina-Manmohan agreement, if successfully implemented, will serve as a confidence-building measure to be replicated elsewhere in the Subcontinent. The memorandum comes with the same formula of ‘economic engine as confidence-building measure’ that had gone into the stillborn Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline. That project was abandoned in 2009 by India even before it got a fighting chance (see Himal July-August 2005, ‘Magic pipeline’), under pressure from the United States. Hopefully, the Hasina-Manmohan memorandum can tackle the geopolitical shoals better, for it is not going to be a smooth ride.

Certainly, caution is in order. Given the depth of past animosities, it is far from certain that one agreement will be enough to spark trade, commerce and economic growth this vital corner of Southasia. The success of the 1998 Sri Lanka-India free-trade agreement does point at great prospects for the 2010 communiqué, but Sri Lanka is an island economy, psycho-politically at arm’s length from Subcontinental geopolitics. The India-Bangladesh theatre carries the baggage of animosity on one side and disinterest on the other; under the circumstances, there are some who suggest that the communiqué be quietly allowed to gain traction rather than be debated in the open.

The most significant challenge will come from delay in implementation of the agreement, and in the economic benefits that should accrue. The political polarisation in Bangladesh is such – and the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) can be expected to play its anti-India card with vehemence – that the fate of the memorandum today hangs in the balance, a year after it was signed. In India, the problem is with the myriad agencies involved, the schisms and distance between the Centre and the stakeholder states, and bureaucratic inertia. The optimists put their faith in the opportune political alignments in both Dhaka and New Delhi, which they hope will see through the economic and geopolitical breakthrough.

The implementation of the Hasina-Manmohan communiqué would boost the Bangladeshi economy, and the catalytic reverberations would be felt far and wide. The Northeast would benefit, as would larger India, Nepal and Bhutan. To succumb to hyperbole, the economic ripples would in time lap at the shores of Southeast Asia, and the example of the Dhaka-New Delhi collaboration would help loosen the difficult knot that is the India-Pakistan-Afghanistan theatre.

Three-way imperative

After years of obdurate standoff, the India-Bangladesh opening became an imperative for the New Delhi government, the states of the Indian Northeast and for Bangladesh. As far as the Northeast is concerned, the conversion of Bangladesh from a semi-hostile neighbour to an enthusiastic market would hold the prospect of enhanced economic autonomy. No longer would the region be kept at arm’s length from the port of Chittagong, and, starting with haat bazaars at the frontier, economic efficiency could be sought through trade.

For India at large, a rapprochement has become urgent. As an aspiring world power seeking permanent membership at the United Nations Security Council, New Delhi needs to prove its friendships in the Southasian neighbourhood. Eyeing the growing Chinese involvement in the Subcontinent, from the ports of Sittwe in northern Burma to Hambantota in southern Sri Lanka to Gwadar in Balochistan, New Delhi is in a mood to reach out. There are deeper complications in an India-Pakistan rapprochement, which is why Bangladesh becomes the natural choice for a New Delhi seeking to build bridges with its estranged land neighbours.

As a humongous country and economy that encompasses the larger part of Southasia, which trades largely outside the region, India is thought by many to have the least interest in commercial links with the immediate neighbours. Those who regard New Delhi as ‘India’ would indeed hold this mindset, but the interest of the poorest, most populated regions of North and Northeast India requires Indian strategists to look beyond capital-centric geopolitics. As the states of the Northeast begin to make increasing demands on New Delhi for more elbow room, there are the makings of a surge in demand for rapprochement from within India. Before long, not just the Northeast, but nearby regions from Bihar to eastern Uttar Pradesh will be asking for lowering the drawbridge to Bangladesh.

If New Delhi has geopolitical imperatives for developing a relationship with Dhaka, the latter has to reciprocate for the sake of its people. A country with a large population and modest natural resources, Bangladesh’s economic growth has to rely on production of goods and services, which requires both investment and trade. Now as in the past, the largest prospects for investment come from India. Economic growth in the Ganga-Brahmaputra (Padma-Jamuna) delta is certain to reduce the mass of migrants entering India, a dynamic that has provided the excuse for decades of communal radicalisation from Assam to Maharashtra. If Bangladesh were to rise from its present economic growth rate of about six percent to about eight percent – entirely possible with transit, investments and exports – experts project a sharp fall in the outflow of migrants. One only has to see how the economic spurt achieved by Bihar under Chief Minister Nitish Kumar has seen a dramatic drying-up of agricultural migrants to Haryana and Punjab over the last few years.

Farther afield, those who pooh-pooh economic growth based on the regional trade opening need only look at the Sri Lanka-India relationship. The bilateral free-trade agreement (FTA) signed between Colombo and New Delhi in 1998 led to fast-paced developments, including a reduction of Sri Lanka’s balance-of-payments deficit with India from a ratio of 1:9 to just 1:3 within the first decade. Today, Sri Lanka promotes itself to the multinational companies as a stepping-stone to India, and Indian businesses themselves are moving to the island to sell back. Says a Dhaka businessman, ‘They ask us to learn from Southeast Asia about open economies, but there is the example of Sri Lanka right in front of our eyes.’ (The person quoted did not want to be named, as was the case with several individuals in Dhaka and New Delhi interviewed for this article.) If Colombo can evolve as a conduit to India, Chittagong – presently being developed for deep-water capability – is sure to develop in the same manner for India and the larger Southasia. The port of Mongla, today little more than a set of sleepy jetties on a Ganga/Padma distributary near Khulna, could likewise rise to provide relief to overextended Indian ports on the Bay of Bengal seaboard.

The Bangladesh-India opening could also be a harbinger for the larger goals of Southasian – and even Asian – economic integration. It would be catalytic for inter-SAARC relationships, India-Nepal, Afghanistan-Pakistan and, all important, India-Pakistan. The concentric region to SAARC known as BIMSTEC, stretching from Nepal to Thailand and to be headquartered in Bangladesh through a decision made in January 2011, would also take energy. Once the benefits of trade and transit become obvious, it will provide civil-society activists and opinion-makers all over Southasia with the weight to more forcibly argue against the ultra-nationalist mindset that has long kept the regional economies locked in. What are known as ‘track two’ efforts can lay out the prospects, but it is decisive political action by representative governments that can overcome the hurdles to release commerce, leading to regional peace and stability. The Manmohan-Hasina agreement points in that direction.

Great wall of mistrust

One recent winter evening after a boat tour of the Sundarban mangrove region, this writer was on a ferry headed for a landing, from where we were to drive to Dhaka. The lower deck was packed shoulder to shoulder, and conversation was picking up. Suddenly, the vessel grazed an underwater sandbank and came to a halt. All because of Farakka! was the immediate response of more than one passenger. Such are the deep-set feelings over the unilateral construction of the Farakka Barrage by India, started in 1960. In one stroke, this act by the upper-riparian country – building a barrage to divert a large part of the Ganga/Padma water into the Hooghly River to de-silt the Kolkata port – destroyed trust, while helping to stoke latent anti-Indianism. Many Dhaka experts claim that the resultant impoverishment in eastern Bangladesh is one cause of the out-migration that India has had to suffer. As the ferry struggled free of the sandbank, it was clear that the rage has not subsided nearly two decades after the Farakka Agreement was finally concluded in 1996, during Sheikh Hasina’s first term in office.

There were other reasons for anti-Indianism, to be sure, even though some thought that India’s military involvement in the liberation of Bangladesh would have made Dhaka the most ‘pro-India’ capital in Southasia. In part, this sentiment is the outcome of the natural small-country xenophobia vis-à-vis an overwhelming neighbour. The definitive departure came when two autocrats in succession, the late General Ziaur Rahman (1977-81) and General Hussain Muhammad Ershad (1983-90), required the prop of anti-Indianism to provide ideological legitimacy to their regimes. While Sheikh Mujibur Rehman was alive after successfully leading the liberation struggle the creeping anti-Indianism was held in check, but not after his assassination in 1975. Says one political scientist, ‘Post-1975, the government itself became anti-Indian – there was a concerted attempt to see India as hostile and obstructionist. Pakistan’s tactical policy towards India was adopted as Bangladesh’s strategy towards India. The war games of the Bangladeshi military identified India as the enemy as the war manuals of Islamabad were incorporated by Dhaka.’

The Awami League of Sheikh Mujib and his daughter, Sheikh Hasina, has long been seen as ‘soft’ on India, and the anti-India banner carried most forcefully by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) of Gen Zia’s widow, Begum Khaleda Zia. The last general election, in December 2008, was fought by the BNP on the plank of sovereignty, anti-Indianism and Islamisation. This kneejerk attitude against India that the BNP nurtures has hit the Bangladesh economy hard on more than one occasion over the years, as exemplified by the Tata debacle of mid-2006. The Indian multinational had come in with a promise of investing some USD 3 billion dollars in two power plants, a steel mill and a fertiliser factory, but the refusal of the then-BNP government to supply natural gas made it back out. As one Dhaka analyst concedes, ‘In essence, the Bangladeshi side over-negotiated, based on the need not to be seen as pro-India and the Tatas departed. Over-negotiation is a Bangladeshi weakness.’

Sadek Khan, a prominent Dhaka commentator, parses the polity’s attitude towards India in this manner: ‘The middle class favours a better relationship with India, and the intellectuals are warm towards the memorandum. But the public at large is more sceptical. In the army and in the higher business circles there is scepticism, with the members of the India-Bangladesh Chamber of Commerce and Industry themselves complaining that New Delhi gives too little and demands too much.’ Mahbubur Rahman, former Chief of Army Staff and presently member of the Standing Committee of the BNP, repeats an observation of the kind heard here and there in Dhaka, ‘We do not want India as a big brother. We want to see it as an elder brother with affection and love for the younger brother.’ The attitude also rankles Deb Mukharji, former Indian high commissioner to Bangladesh, who believes that Bangladesh should not seek magnanimity but fairness (see “A ‘fair-plus’ deal“).

Against the wall of mistrust, what does Bangladesh have that is so crucial to India? The answer lies in one word: transit. And the most significant concession made by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in the New Delhi talks in January 2010 – some would say courageously, others rashly – was to override the mindset against providing transit. In essence, she decided not to over-negotiate.

What price transit?

The issue of transit holds near-mythical powers in the mind of many a Dhaka commentator, who believe this to be the only handle that Bangladesh has on its larger neighbour. The deltaic Bangladesh stands between mainland India and the seven states of the Northeast. The Siliguri corridor, a narrow stretch (sometimes just 21 km wide) between the northwestern head of Rajhsahi Division and Jhapa district of southeastern Nepal, is the only access for Indian transmission lines, road and rail. Transport through Bangladesh is vital for India on several planes: for the mainland to reach the Northeast in a straight line, for the landlocked Northeast to get to the sea, and to access Southeast Asia through the Bangladeshi flats rather than the roundabout northeastern hills.

As with the case with the Tatas, over the decades the Bangladeshi side has filibustered on the transit matter as well, in the hope of extracting extravagant concessions. While India clearly loses significantly in the absence of transit through Bangladesh, New Delhi obviously calculated long ago that it can bear this loss, even if it means stifling the Northeast economy. If the northeastern states – from largest Assam to tiny Tripura, bounded on three sides by Bangladesh – had more clout in New Delhi, there is no doubt that Indian diplomacy would have worked overtime to sort out the transit matter before now. In recent years, the Northeast politicians have become increasingly confident vis-à-vis New Delhi, hence more able to voice their demands for direct links with downstream Mymensingh, Bogra, Sylhet and Dhaka.

The debate in Dhaka over the years has centred on the politico-economic price to extract from New Delhi for extending transit concessions. Some have feared that if Dhaka demanded too much, New Delhi would simply decided to bide its time. As far as the link to Southeast Asia is concerned, some in the Indian bureaucracy seem of a mind to bypass Bangladesh altogether, by connecting to Burma via Nagaland. At the other extreme are those who deny the importance of transit in toto. One former secretary of power, A N H Akhtar Hossain, says, ‘Transit is a political slogan to begin with. It also holds little meaning because we cannot provide the infrastructure of international standards required by India. The Jamuna Multipurpose Bridge, for example, was not built for heavy traffic or goods. The roads will have to be widened, but how will the government go about acquiring land for this?’

The Indian side is clear not to rush Bangladesh on transit, even though, as one New Delhi negotiator says, ‘transit would be a good thing, it would make our lives easier.’ Nagesh Kumar, formerly chief of RIS, a think tank focused on policy research on economic issues supported by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, says, ‘The transit facility through Bangladesh would benefit both economies. A RIS study in 2008 showed that there would be a billion dollars in direct income for Bangladesh from India-to-India transit. You must also count the spillover benefits of new highways in terms of economic activity and employment.’ There is scepticism among some in Dhaka that India may not use the transit facility when it is finally made available. Nagesh Kumar, presently the chief economist for the UN regional body for Asia ESCAP in Bangkok, says in response, ‘There is no doubt India will use transit through Bangladesh once it becomes available. India will save money, that is certain. If a business can save two or three percent of costs through transit, that is a great margin, provided there are no restrictions.’

Even though the Hasina-Manmohan communiqué provides for transit, the mood in New Delhi seems to be to wait and watch, other than to use a special facility provided for transport of goods to a power project in Tripura. Says the Delhi negotiator, ‘Let economic gravity play its role. It is important to respect Bangladeshi sovereignty and not to demand transit as a right and force Dhaka’s hand. Bangladesh is building a deep-sea port in Chittagong, it will need traffic.’

Stellar alignment

In December 2008, following two years of military-backed caretaker government, Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League swept into government in a landslide (263 seats in Parliament out of 300), on the plank of change, employment, law and order, and long-pending war-crimes trials relating to the events of 1971. The decisive Awami League victory allowed the prime minister to unabashedly reach out to New Delhi. The political alignment in Dhaka was complemented in New Delhi, with the reinstatement of Manmohan Singh’s United Progressive Alliance (UPA-II) government in a stronger position than the earlier (UPA-I), following the elections of April-May 2009. Making a deal with Bangladesh was important to India’s economist prime minister, whose belief in soft borders had been stymied on the Pakistan front. (In January 2007, addressing the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry in New Delhi, he had said: ‘I dream of a day … when one can have breakfast in Amritsar, lunch in Lahore and dinner in Kabul. That is how my forefathers lived. That is how I want our grandchildren to live.’)

Second-time Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina decided to redefine the relationship with New Delhi, a high-risk gamble in the context of the toxic political polarisation of Dhaka. In forming her government, she defined a new team including ‘greenhorns’ in the cabinet and outside advisors into her inner circle. The latter include Harvard-returned academic Gowher Rizvi and Tariq A Karim, High Commissioner to India, who was given minister-of-state rank to emphasise the importance of New Delhi (see ‘Strong alignment, again‘). While she certainly would have taken advice, the overall agenda on India is defined by the prime minister herself – who, a close associate says, has matured politically since her last time in government (1996-2001), aided perhaps by time for introspection during a year’s incarceration by the caretaker government in 2007-08.

The most dramatic move on Dhaka’s part was to ‘facilitate’ the apprehending, in November 2009, of the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) militant leader Arabinda Rajkhowa, who had been hiding out in Bangladesh. Against the backdrop of India’s repeated complaints of Northeast militants finding refuge in Bangladeshi territory, Sheikh Hasina’s action did not fail to impress the political class in New Delhi. One official in her team spoke of an ‘immediate turnaround’ in the negotiating posture of Indian officials after Rajkhowa was arrested: ‘Suddenly, there was flexibility and friendliness on their part, and the talks moved smoothly.’

On a state visit to New Delhi from 10-13 January 2010, the Bangladesh prime minister received an elaborate welcome from the Indian political class. She responded in kind by visiting each of the samadhi sthals along the banks of the Jamuna, the memorials to Mohandas K Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. Then, in a 50-point joint communiqué signed on 12 January, the two prime ministers agreed to put in place a comprehensive framework of bilateral cooperation, mostly importantly on water resources, power, transportation and related ‘connectivity’. They also agreed to strengthen the ‘forces of democracy and moderation’, resolving to prevent the training of and sanctuary to militant and insurgent organisations.

In the communiqué, the two sides agreed to comprehensively address all outstanding land-boundary issues, and to amicably demarcate the maritime boundary. Ashuganj in Bangladesh and Silghat in India would be declared ‘ports of call’, and Dhaka would allow the use of the Mongla and Chittagong ports for movement of goods to and from India through road and rail. Dhaka ‘conveyed its intention to give Nepal and Bhutan access to the two ports’. (In mid-2010, New Delhi also confirmed that Indian territory could be used for this purpose, see accompanying article by Mallika Shakya.) The construction of a railway line from Akhaura on the border to Agartala, the capital of Tripura, was to be financed by a grant from India; and the broad-gauge railway link at the Bangladesh-India border at Rohanpur-Singabad would be made available for transit through India to Nepal.

On the all-important matter of water, the two prime ministers agreed that discussions on the sharing of the Teesta River should be concluded expeditiously through the Joint Rivers Commission, a body created the year after Bangladesh’s birth. Prime Minister Singh reiterated that India would not take steps to harm downstream Bangladesh vis-à-vis Tipaimukh, an 1100-megawatt hydropower project on the Barak in Manipur. India also agreed to make available 250 MW of electricity. To encourage Bangladesh exports to India, the two prime ministers agreed to address the removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers as well as port restrictions, and to facilitate the movement of containerised cargo by rail and water. India would support the upgradation of the Bangladesh Standard Testing Institute, in order to help the certification of Bangladeshi processed food exports. Finally, India announced a line of credit of USD 1 billion for a range of infrastructural projects from power stations, railways, highways to waterways. The loan was provided at 1.75 percent interest over 15 years, with a five-year grace period.

The ticking clock

Hidden behind a veil of staid diplomatic language, the Hasina-Manmohan communiqué represents a warm embrace from Bangladesh and a promise of reciprocation by India. Allowing transit through Bangladesh territory and access to Mongla and Chittagong represent a dramatic gesture on the part of Dhaka, and the Bangladesh citizenry now waits to see whether India will follow through. Much of this will become evident when Prime Minister Singh visits Bangladesh towards the middle of 2011, as is expected, which will have to be the time for stock-taking.

The most obvious risk to the agreement’s follow-through is the polarised politics of Dhaka, where the BNP stands ready to exploit its very signing. While the Bangladeshi gestures on security (the ‘facilitation’ on Rajkhowa) and transit are of a kind that would take immediate effect, the economic benefits that accrue from India’s gestures will be slow to flow, and hard to ascribe to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s diplomacy. Likewise, the expected estimated income of about USD 1 billion annually from the use of Bangladeshi territory for transit by India would accrue only after the required infrastructure is put in place. The same will hold true for the USD 1 billion line of credit that has been provided by India. ‘When you raise public expectations that the economy will gain billions of dollars within a few years, and the money does not flow, that will give rise to distrust,’ says a Dhaka businessman.

A year has passed since the Hasina-Manmohan communiqué was signed, and implementation has been at a snail’s pace. High Commissioner Karim maintains that the window of opportunity will begin to close as the two governments attain the midpoint of their respective terms of office; thereafter, populist nationalism will define the discourse, more so in Dhaka than in New Delhi. For Bangladesh, this midway point will arrive around July 2011; for India, November 2011. By all accounts, the dangers within India are primarily bureaucratic; within Bangladesh, primarily political.

One Bangladeshi negotiator believes that the entire gamut of the New Delhi leadership – from Prime Minister Singh to Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee, Minister for Commerce and Industries Anand Sharma, Montek Singh Ahluwalia at the National Planning Commission, National Security Advisor Shiv Shankar Menon, and the hierarchy at South Block – is keen to follow through on the promises made in the communiqué. The obstacle they say, with increasing concern, lies in coordinating the large government apparatus of India, including the line ministries at the Centre as well as the individual stakeholder states.

A senior official in Delhi who has followed the India-Bangladesh matter does not agree with the blame placed on the Indian bureaucracy. He says, ‘On the India side it is a matter of capacity to act, not of will. On the Bangladesh side, it seems to be both, with the bureaucracy really slow. There were 36 matters that we agreed during Sheikh Hasina’s visit a year ago. Three are pending with us, and 12 have been addressed from our side. That leaves 21, and all are stuck in Dhaka. You just have to take the Tata deal as a case in point, there were so many hurdles placed by the Dhaka bureaucracy that in the end the Tatas walked away.’

What the Dhaka negotiators want is for India to open up its market to Bangladesh the same way that this has been done for Nepal and Sri Lanka. The various tariff and non-tariff barriers imposed by New Delhi have created obstacles for Bangladeshi access to the Indian market. The state politics within India are acting as a drag on New Delhi. West Bengal is wary about the Teesta waters, and the textile lobby in South India – particularly Tamil Nadu – would be happy to scuttle any attempt by New Delhi to go soft on Bangladeshi textiles. The sharing of waters is another area where Dhaka commentators seek proof of New Delhi’s reciprocation of goodwill. With the memory of Farakka still rankling, there is deep interest in how the Teesta waters will be divided between West Bengal and Bangladesh. There are also fears over the Tipaimukh project, and an unwillingness to believe the assurances given in the communiqué itself.

Says a worried Bangladeshi official in late January 2011, ‘Teesta, pending land-boundary matters and trade liberalisation are the three critical pending issues at the start of 2011, a year after the Hasina-Manmohan communiqué was signed. The Phulbari-Banglabandha point in the north has been opened for India-Bangladesh trade, whereas earlier it was limited to Bangladesh-Nepal. On the whole, though, India has been disappointingly slow in lifting the barriers to help Bangladesh. India’s strong textile lobby is stonewalling. The magnanimity shown by little Bangladesh in the communiqué has not been reciprocated anywhere near to scale by giant India. Ordinary Bangladeshis are beginning to fret.’

A Dhaka business executive with a holistic view of the economics and politics has this to say: ‘Sheikh Hasina has taken a risk with the agreement, but she should have come to Parliament and openly discussed the memorandum. She has not done that. For its part, India must understand that Bangladeshis are a practical people; so acute is our struggle for survival, we are not fanatical at all. The Indian bureaucracy is the main hurdle, and they should understand that China has overtaken India in trade volume. The Reserve Bank of India creates so many restrictions that it hampers trade flows.’

For every Dhaka mindset, there is a counter-argument in Delhi. According to an Indian official following the bilateral trade, the demand for lifting restrictions on trade is a bogey. He points out that India has waived duty on eight million pieces of garments from Bangladesh, but the quota has not been fully utilised. He says that of the 62 items on India’s ‘restricted list’ with Bangladesh, 41 are textiles. ‘This is a big problem, as India’s textile industry is sensitive to the matter. The only answer is to integrate industries, to coordinate production and processing across the border.’ Adds the official, ‘There is potential for up to USD 6 billion of Bangladesh exports annually to India, compared to USD 2 billion at present. However there is little supply capability for export of, say, gas, fertilisers or jute. There is a clear need for investments, and India is the most proximate source.’

As for resistance among Indian business for an open economic regime, Nagesh Kumar of ESCAP believes the matter is manageable: ‘I do not think anyone would really be threatened by Bangladeshi business entering the Indian market. Some Indian business lobbies will of course resist the liberalisation measures, but it is the job of the government to be fair and forward-looking.’

Political tribalism

The poisonous polarisation in Dhaka looms as the most significant pitfall for the rapprochement and growth represented by the Hasina-Manmohan agreement. Nurul Kabir, editor of the New Age daily in Dhaka, gives a sense of the deep-set animosities when he suggests, ‘Bangladesh is developing into a tribal society, with two tribes known as Awami League and BNP.’ Indeed, the polity is marked by a near-absolute divide between the two parties, led by the daughter and spouse, respectively, of two slain leaders.

According to a despondent former foreign secretary of Bangladesh, the widening political chasm is hazardous for implementation of the communiqué, to say the least. This gentleman’s view is dark, at several levels: ‘Sheikh Hasina is all-powerful right now, but she faces formidable obstacles. Within the Awami League, the old leaders and MPs are disgruntled because she has brought in greenhorns and technocrats. They are waiting to pounce. Many in the army are unhappy that the embrace with India is too tight. The prime minister feels the need to go all-out to finish off the opposition, otherwise the BNP will finish off the Awami League – that is how bad it is.’

The BNP position on the bilateral communiqué is voiced by Shamsher Mobin Chowdhury, another former foreign secretary and currently vice-president of the BNP – and it is rejectionist (see ‘Where’s the documentation?‘). In fact, Chowdhury claims not even to have seen the text of the memorandum, given that it has not been put up on the Bangladesh government website or otherwise officially published. There are a few in the Dhaka intelligentsia, however, who believe that the communiqué has achieved a fait accompli from which the BNP cannot backtrack if and when it comes to power. Says the Dhaka businessman quoted above: ‘Of course the BNP is vocally opposed to the memorandum, but its remonstrations have been mechanical. I have not detected a serious rejection, there is no mobilisation against the agreement.’

Sheikh Hasina has staked her political career on the implementation of the communiqué. There is a general sense among those who support the agreement – and these are not only the supporters of the Awami League – that the prime minister will need a second term in office to see through what she has started. With Bangladesh’s goodwill seen in the awarding of transit facility to India, the latter must, keeping the interests of its Northeast paramount, make the required decisions on what the Dhaka government needs at the start of 2011. This means unhindered access to the Indian market, agreement on the Teesta, and confirmation that downstream interests will not be tampered with on the Barak.

The senior official from New Delhi has this to say regarding bilateral water issues: ‘On Teesta there has been forward movement, and the interests of West Bengal and Bangladesh can be reconciled. On Tipaimukh, we have done nothing that should worry Bangladesh. We have taken their members of Parliament to the site to reassure them, and are willing to even make it a 50-50 joint venture. On Farakka, we are sharing the water-flow data and Bangladeshi technicians are involved. Both sides know that India is getting less flow than agreed upon.’

The immediately-accruing advantage for India on security and transit must translate into long-term economic growth for Dhaka. The Bangladeshi society has gone as far as it can go with innovations in industry and the NGO sector, it now needs to connect up with the larger Indian and Southasian markets to realise its full potential. In the process, New Delhi will help itself by assisting its Northeast as well as Bangladesh. Without getting into hyperbole, the possibilities for all of Southasia are immense if the promise of the communiqué bears fruit.

High Commissioner Tariq Karim says Bangladesh arrived at the concessions it made in January 2010 by looking at the bilateral issues as cross-cutting: ‘If we were to look at the line items in a unilinear fashion, we will get caught in a bureaucratic morass. It was important to take the entire gamut of issues and sectors together and give a political push to get us out of the logjam.’ One aspect of non-linear thinking would be this: with New Delhi’s helping hand on trade, Bangladeshi industry would grow, lifting the gross domestic product high enough to reduce the flow of job migrants into India.

The hope is that at least this quadrant of Southasia could go back to being a region of soft borders, with railways, roads, transmission lines – and people – crossing borders without challenge. That will be the day when the border fence, which has been so assiduously erected to separate the people of India and Bangladesh at the grassroots, will begin to rust and crumble.