From Himal Southasian, Volume 10, Number 1 (JAN/FEB 1997)

By Kanak Mani Dixit, with research by Ganesh Khatri, Ramyata Limbu and Sangeeta Lama.

It does not seem to shame nor needlessly bother Kathmandu´s ruling classes that highland peasants by the hundreds of thousands leave the country every year to work the most wretched jobs in the plains of India.

Nepalis migrate to the plains of India for the same reason that migrants have abandoned their homes and hearths the world over through history. It is the economics of desperation. Because their unproductive little farms are unable to provide sustenance, high-landers by the hundreds of thousands descend to India in search of livelihood. In extreme cases, they leave solely for the purpose of removing an extra mouth to feed at home.

At a time when, after decades of neglect, the issue of the export of Nepali women to brothels in metropolitan India is finally getting a degree of notice, the much larger export of menial labour continues to receive scant attention of planners and scholars. Cumulatively, the remittance by migrant labour make a singular contribution to the national economy, but they find no mention in national economic calculations, and certainly not in the figures and forecasts of the National Planning Commission.

The volume of misery that is represented by what is thought to be more than a million individuals from a national population of 21 million leaving home to work as an underclass in the plains is indeed large, and it is lamentable that it should go unremarked. Such is the official and scholarly apathy on the subject of Nepali labour in India—akin to the indifference towards human-back portering in the hills (see Himal Nov/Dec 1995)— that one can reach no other conclusion than that the phenomenon is regarded as a national embarrassment.

Pretending that migration for basic employment does not exist or does not matter will not make it go away, however, and the Nepali state is dutybound to recognise the issue and address the extreme economic imbalance and lack of progress which makes peasants continue to seek paltry pickings in a neighbouring country.

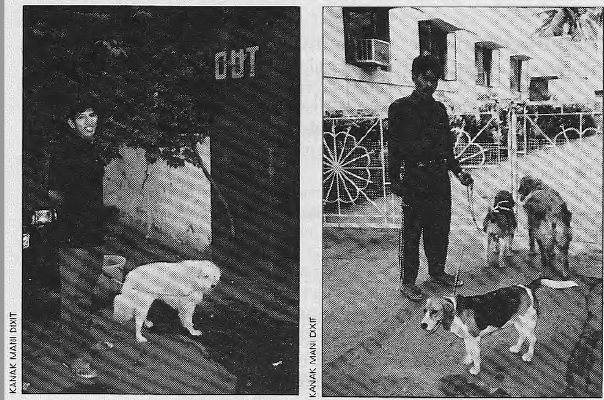

In the absence of information collection efforts, one has to rely on anecdotal information to gauge the extent of the Nepal-born labour force in India. For example, it is well known that a Kathmandu person can never get lost in metropolitan Delhi´s complex maze—he can receive continuous guidance from the Nepali-speaking watchmen , workshop assistants and restaurant boys that populate every neighbourhood of India´s capital.

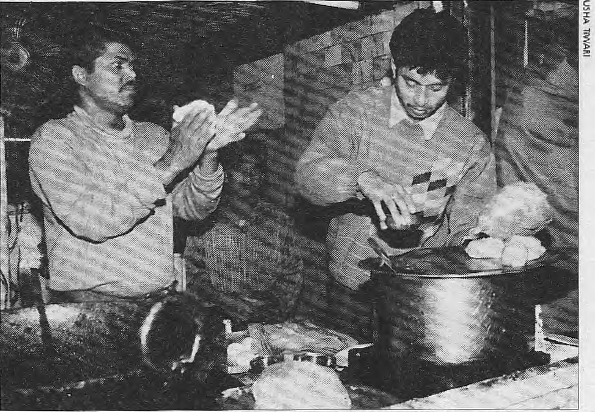

Little Bajhang

Scattered incidents and the occasional research report also give evidence of the spread of Nepali working class across the length and breadth of India. When the New Delhi police combed the Vasant Kunj middle class enclave following the arraignment of Tika Ram on a multiple murder charge (see following article), they found that fully 400 out of 1,200 households kept servants from Nepal. At Saagar Restaurant, a popular South Indian eatery in the cityís Defence Colony market, it is possible to order your meal in Nepali most of the young workers are from the West Nepal districts of Gulmi and Pyuthan.

Punjabi landlords, and also those in Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh, use Nepali workers as security guards and as seasonal labour for the fields as well. In May this year, Indian newspapers briefly noted the execution-style killing of eight Nepali labourers by militants at a stone-crushing factory in Kashmir Valley.

Across the Himalayan rimland of India, Nepali road gangs build and maintain mountain highways. At the Subcontinentís other extremity, in and around the city of Bangalore, villagers from Bajhang District in Nepalís far west have established a well-organised labour monopoly for themselves. According to a Swiss anthropologist who has studied this trans-South Asian phenomenon, Bajhang survives on the basis of remittances from Bangalore.

While the Bajhang-Bangalore hookup has been extraordinary, the distribution of labour tends to be more spatial. The population of the poverty-stricken western hills, for example, migrates to adjacent areas in India. Besides going to the nearby plains, some Nepalis from the far west also hike across into Uttarakhand, whose own menfolk migrate to Delhi to find better work. In Uttarakhand, Nepalis (called Dotiyals) serve as coolies in hill stations like Nainital and Mussoorie and carry loads for pilgrims and the pilgrims themselves at holy locations such as Gaumukh and Kedarnath.

Even though the people of east Nepal are somewhat better off than those of the far-west, they too migrate by the tens of thousands to the outlying areas, gravitating to Calcutta and the industrial centres of Bihar and West Bengal, or to the Northeast.

Says Garima Shah, a Delhi-based Nepali activist and social worker: “Young boys in restaurants and dhabas, illiterate factory labourers, domestic help, drivers, chowkidaars, ayahs, this is the lot of the Nepali migrant. A few lucky ones make it to the level of lower division clerk in a government office, cashiers, receptionists, and hawaldars in the Indian police.î She adds, “Nepalis are everywhere, in the low-paying jobs which are most visible. There is a saying among us here, that Nepali ra aloo jaha pani painchha (Nepalis and potatos, they are found everywhere).”

The Perfect Fit

Serving as a domestic and commercial underclass in the plains is not a tradition handed down to the present Nepali generation by earlier ones. If anything, this is a 20th-century phenomenon and is evidence of the relentless economic marginalisation of Nepalís hinterland in the modern era.

The Nepali hillman´s travel to muglan (plains) for work probably began with recruitment into the army of British India after the 1814-16 Anglo-Nepal war. For the first time, men from the hills of Nepal spent time in the lowlands, in garrison towns. “Gurkha” evolved as a brand name for integrity and loyalty as the batmen to British officers became the prototypical household help. Ground was being prepared for Nepalis to gain jobs with the Indian middle class households a full century later.

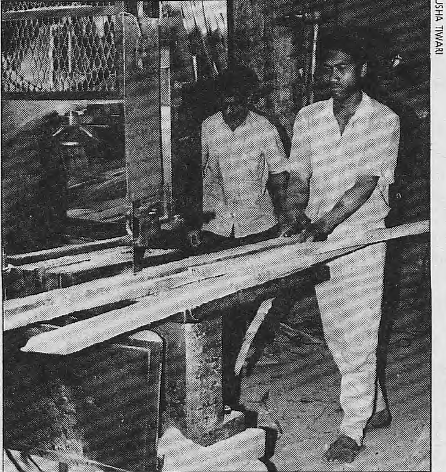

Besides Gurkha recruitment, Nepal also became a source of brawn starting in the mid-1800s, when the peasantry was encouraged to migrate eastwards along the duars (the strip of plains below the hills of Darjeeling and Bhutan) to Assam valley, and the far-eastern hills from present-day Arunachal all the way to northern Burma. The colonials required a pliant labour force to help open up forest lands for lumbering, settlement and tea plantations, and the unlettered, unexposed Nepali highlanders provided the perfect fit.

Usurious conditions in Nepalís villages created by taxation levied to finance expansionary wars and occupation, and later the rapacious system of Rana family rule, provided the push factorsî for this process of migration to start and be sustained. In modern times, an expanding population ensured the continuing need for migration to ensure survival.

Indian census reports show that the Nepal-born population increased significantly in India only after 1951, indicating that the volume of migratory labour suddenly expanded in mid-century. According to the 1971 census of India, there were 1.3 million Nepal-born Nepalis living in India. Migrant organisations such as the Emigrant Nepali Association claim that this figure is now up to about three million. (See accompanying article by Dilli Ram Dahal on the problem with numbers.)

In the 1960s and 1970s, the eradication of malaria from the Nepal tarai and official encouragement for highlanders to colonise these jungled plains also provided an outlet for migratory pressures. The tarai forests got used up, but there was continuing need for the peasantry to find means for sustenance and survival. In the end, it burst through the open Indo-Nepal border (guaranteed by the 1950 Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship) to take advantage of work opportunities, however menial, that became available in the modernising economy of independent India.

Among other things, an Indian middle class had grown through the 1950s and 1960s, and Nepalis came in time to provide household help as darbans (watchmen) and kitchen help. Industrialisation and the development of roads and other public infrastructure also threw up a great demand for unskilled labour, and willing Nepali hands arrived to take up the chores.

The exodus from the hills has, if anything, escalated over the decades since. Today, at roadheads all over Nepalís tarai, from Mahendranagar on the western border to Kakarbhitta in the east, there is a continuous flow of Nepalis on the way to jobs in India or returning on leave. All over the Nepali hills this past October, as happens every year at the time of the Dasain festival, Nepali menfolk arrived home by the tens of thousands bringing gifts, trinkets and household items, to snatch a few moments with parents, children, wives before heading back down for another year of labour.

The Migrant and the Social Scientist

The need for a significant proportion of Nepalís population to descend to the Indian plains in search of menial work indicates the depth of the economic depression in the hills, particularly in the west of the country where there is more poverty.

Mahendra Lama, Associate Professor of South Asian Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, lays the blame for the extraordinary situation squarely on the shoulders of the Kathmandu establishment. Says Mr Lama: Successive Nepali governments are responsible for the plight of the immigrants. The national economic, political and social management has been extremely poor, with the result that even today there are no worthwhile opportunities within the country for the growing population.

K.B. Shahi agrees. A school teacher before he left his district of Bajura to land a job at the Philippines Embassy in Delhi, Mr Shahi says it was economic necessity that forced him to move. Back home, development is nil,” he says. “Here, at least one is assured of basic amenities. My three sons and one daughter speak and write better Hindi than Nepali, but that is a small price to pay for what we get here that we could not back home in Bajura.”

Laxmi Prasad Upadhaya, Chairman of the Karnataka-Kerala Joint State Committee of the Emigrant Nepali Association, says, “Nepalis come to India to work because the socio-economic conditions at home are bad, and also because there is an open border. The government is unable to provide for education and health.”

Swiss anthropologist Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, in her study of Bajhang, found that out-migration is a survival move carried out in response to the inability to eke out a subsistence by adapting to the existing social relations of production, or of their inability to revolt against the existing socio-economic order. In contrast, the members of the dominant class of Bajhang have several alternatives at their disposal and do not need to migrate, she says.

While the socio-economic deprivation facing the Nepali population is well documented and is by now a matter of general knowledge, there is paucity of data on Nepali migrant labour, including its extent and life conditions. While carrying out research for this article, it became clear that even the little social scientific research that has been done is dated. The Nepali academicians interviewed could provide little updated information on the subject. Making generalised comments, they constantly harped on the need for further study on the subject.

Ram Chhetri, lecturer in Sociology at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, agrees that there has been little methodical research on Nepalis working in India. He thinks such research is important as it would, besides documenting the life and times of migrants, provide information on how male migration has hit hill agriculture. Migration doubtless has a grave bearing on our economy. We need to know what the migrant numbers are, what kind of labour they do, and how the country can provide alternative income to keep them from leaving.

Says researcher Dilli Ram Dahal, who with colleague Chaitanya Mishra, conducted an indepth study of Nepali migrants back in 1987 that remains the benchmark on the subject of migrant labour: We have no idea since when Nepalis began working in India and what they do there. I think we must study at least two generations of workers to understand the situation. In order to remove ambiguity, it is also important to differentiate between the Nepali-speakers who are Indian citizens and Nepalis of Nepal.”

On the whole, the export of able-bodied men to India has enormous negative consequences on Nepali economy and society, says Mr Dahal. It is futile to discuss human resource development in the country without studying the extent and nature of Nepali job exports to India. As things stand, the Nepalis within Nepal are poor, but those that go to India also get poor jobs.

Life Conditions

In their 1987 report, Mr Dahal and Mr Mishra give the following reasons why the Nepali peasantry found it easy to travel to India for employment: “The 1950 Indo-Nepal Treaty which among other things, formalised this openness of the border, the blurred citizenship identities, the unregulated nature of the border, the easy convertibility of the currencies, the similarities in the organisation of production and the structure of division of labour and thus the easy transferring of skills…”

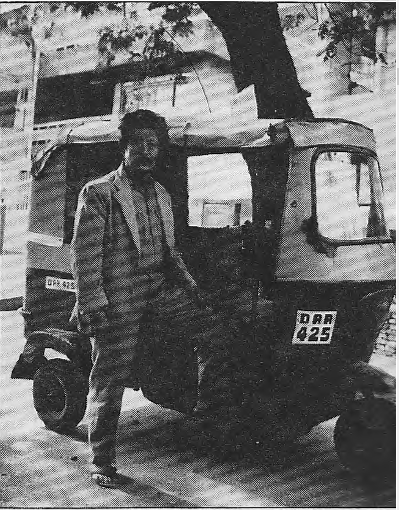

The migrants studied in 1987 by the two researchers were concentrated in the economically-active age group of 15 to 59. Among them, fully 40 percent worked as guards or night watchmen, “which is a lowly job according to status and income”. The other jobs filled by the migrants were as hotel boys (17 percent), technicians (10 percent), sales and business (10 percent), driving and related work (6 percent) and wage labourers (5 percent).

Fully 60 percent of the migrants studied did not manage to send money home—even though that was the reason to migrate in the first place. This figure went up to 80 percent in the state of Bihar, where the income of migrants was lowest. Asked about accumulation of any wealth in India, where they had spent a substantial portion of their working lives, 90 percent of the migrants said they had no landed property, and 84 percent did not have a place to live of their own. Fully 96 percent did not have “transport equipment”, not even a bicycle.

Mr Dahal and Mr Mishra found that the number of migrants who emerged between 1955 to 1965 was much higher than subsequent periods. “The stirrings of the Land Reform Act of 1964 and the consequent unsettled situation” which led to the eviction of tenant farmers might have led to the sudden surge, they suggest.

The two researchers also tried to understand the human suffering and psychological hardship faced by the migrants, who come from hill villages to work in alien urban settings as domestics or in factories, suffering the oppressive heat of lowland summers. There is no doubt that Nepali labourers face psychological trauma, Mr Dahal and Mr Mishra reported. Their main problems were insecurity of jobs, lack of social respect, and a sense of separateness from the local community.

“Migration has helped the mountain and hill areas, and Nepal as a whole, to trudge on,” Mr Dahal and Mr Mishra concluded in 1987. That remains true today, a decade later, and Nepal trudges on.

Peace and Friendship

A number of Nepali organisations, mostly of leftist orientation, have been formed in India to carry out cultural and welfare activities for migrants in India (see accompanying article). A few are politically active and have wide membership. Some of these groups—there are 20 in Delhi alone—serve only the Nepalis of Nepal, others claim to represent Nepali-speakers from all over, including India and Bhutan.

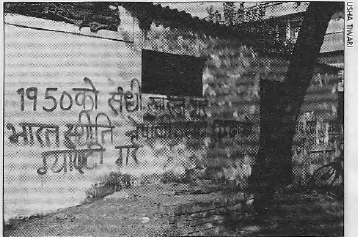

One such group is the All India Nepali Unity Society, which lobbied on behalf of the families of the eight Nepalis killed in Kashmir and made possible the payment of INR 100,000 to each. The Society´s leaders say that it is presently concentrating on seeing that Articles 6 and 7 of the Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1950 are put into practice. These provisions refer to giving equal status to each other´s citizens in terms of residence, travel, trade, ownership and property.

The easy cross-border migration of Nepali labour to India—and Indian labour to Nepal—is made possible by the open border between the two countries, a situation which was formalised by the 1950 Treaty. And yet, the Nepali organisers in India complain that the migrants do not receive the equal treatment that the treaty promises.

Bamdev Chettri, Secretary of the Unity Society, says Nepalis are often prevented from registering their names at the employment offices. They are also not eligible for ration cards for buying essentials, and confront numerous other kinds of discrimination which go against the letter and spirit of the 1950 instrument. According to Mr Chettri, more than 200 petitions filed by the Society on behalf of the Nepali workers are presently pending with the Delhi courts. “Wherever they come from, Nepalis are being discriminated against and we are working for their welfare,” he says.

machine in Thatheri Bazaar, Benaras.

Tek Bahadur K.C., president of the Delhi State Committee of the Emigrant Nepali Association, is also indignant at the treatment of Nepali workers and the various obstacles which hinder their prospects. The Association, which has units all over India, works only with Nepalis from Nepal and provides adult education and skills training to help them overcome the “chowkidaar barrier”. Kathmandu scholars see the need to distinguish between three types of ´Nepalis´ in India so as to provide clear focus on migrants as one category. First, there are the Indian citizens of Nepali origin, concentrated in Darjeeling, Sikkim, India´s Northeast and elsewhere, whose leaders claim a number of some seven million. The Indian Nepali might face some difficulty because he is wrongly regarded as a foreigner, but he has the rights and privileges of a fullfledged Indian citizen.

Then there are the long-settled Nepalis, who, while they might still have land and links in their home villages in Nepal, are quite capable of protecting their interests in India. One official of the Emigrant Nepali Association says that these Nepalis who are “na yata na uta” (neither here nor there) number about one million.

It is the third group, the migrant labourers from Nepal who make seasonal or longer-lasting forays into India, that is the most destitute and without support. This group makes up the lowest rungs of Nepali-speakers in India, and its interests are not high in anyone´s priorities.

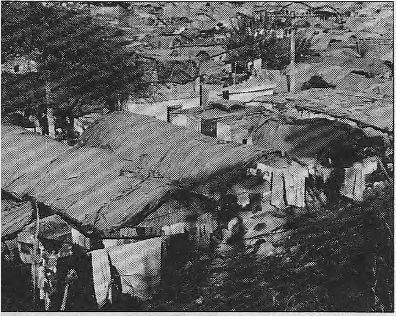

Delhi, Bombay and Bangalore

In the Delhi area, most Nepali migrants live in jhuggies (shantytowns)—many in low-income “trans-Jamuna” areas—under tin-roofs, with whole families crammed into single rooms. Of the estimated 50,000-60,000 Nepalis in the Delhi region, about half work as unorganised labour in the industrial areas of Wazirpur, Narayana, Okhla and Mayapuri. The imminent forced relocation of about 400 polluting factories out of Delhi region, it is said, will affect these Nepali workers badly.

Similar ghettos of ethnic Nepalis are to be found in other parts of India. A survey conducted in March 1995 by the Unity Society in Faridabad, just outside Delhi, revealed 32,000 labourers from the central Nepal districts of Gulmi, Argakhanchi, Syangja, Tanahu and Palpa (as well as another 1000 Indian Nepalis and 500 Bhutanese Nepalis). A December 1995 survey in Jabalpur (Madhya Pradesh) showed 15,000 Nepali citizens from Pyuthan, Dang and Gulmi districts of west Nepal (and 1000 Indian Nepalis).

Sociologist Phanindra Paudyal, who studied Nepali labour in Bombay in 1988, says it is the rural poor of the far-west districts of Doti, Achham, Baitadi and Dadeldhura that land up in India´s financial capital. “With little or no education, and no off-farm experience, these migrants do not have access to the skilled jobs that are available. They find what work they can on the basis of their reputation as ´brave, sincere and honest Gorkhas´, which means working as watchmen,” says Mr Paudyal.

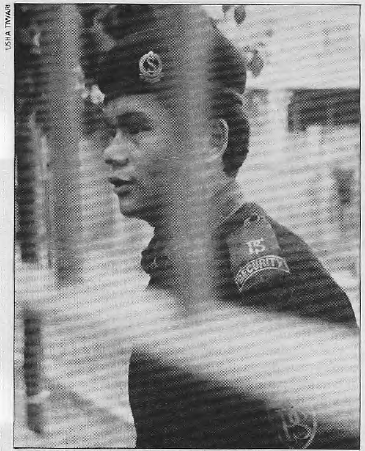

Besides the heroics of the Nepali soldiers in foreign armies, Bombay´s Hindi film world itself has played a significant role in popularising the role of the ´Gorkha´ as watchman. Quite a few film comedians have earned their spurs by clowning in the role of Nepali watchman in the Hindi cinema, wearing the ubiquitous Nepali cap with crossed-khukuri insignia.

Mr Paudyal´s study showed that, on average, Nepali migrants live and work in Bombay for 10 years, starting out as young guards for unregulated housing societies, moving up the ladder as watchmen for private industries, and finally for public sector institutions where perks and facilities are better.

According to Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, Bajhang in of Nepal´s far-west exports up to 60 percent of its male population as temporary migrants all over India. Altogether 20 percent land up in Bangalore and nearby cities of southern India. This strange linkage between the two far-removed regions of South Asia came about as a result of Bajhang´s turn-of-century philosopher-raja, Jai Prithvi Bahadur Singh, having made Bangalore his base upon being exiled by Kathmandu´s Rana rulers.

And so, a population from far-west Nepal tries to create a “little Bajhang” 2000 km from home, while working as guards in Bangalore´s governmental offices, factories and bazaars. “The ability to find the lucrative jobs as watchmen is the outcome of the reputation which several generations of Bajhangis have acquired as brave and sincere workers,” writes Ms Pfaff-Czarnecka.

The researcher says that the Bajhangis´ aspirations are rising, with the younger generation increasingly resentful of the fact that their fathers are of such humble occupations. However, few put their meagre savings in bank accounts and possibilities of advance are curtailed. They are involved, instead, in exploitative “lottery” schemes and they also spend heavily in drinking. Says Ms Pfaff-Czarnecka, gambling is a bane among the migrants. The financial entanglements, in turn, keep the men in Bangalore much longer than planned.

Says Ms Pfaff-Czarnecka: “The life of Bajhangis away from their homes consists in working as watchmen, usually when others are sleeping; in enjoying city life, but while living at the very edges of cities; in meeting other Bajhangis while very seldom entering into relationship with the Indian population.” The Nepalis of Bangalore, she says, do not have ties with the upper strata of society and hence are unable to take advantage of opportunities that do exist in the urban milieu. She concludes: “In Bangalore, the Bajhangis have managed to find an economic niche they are able to exploit, but in this niche their economic marginality is perpetuated.”

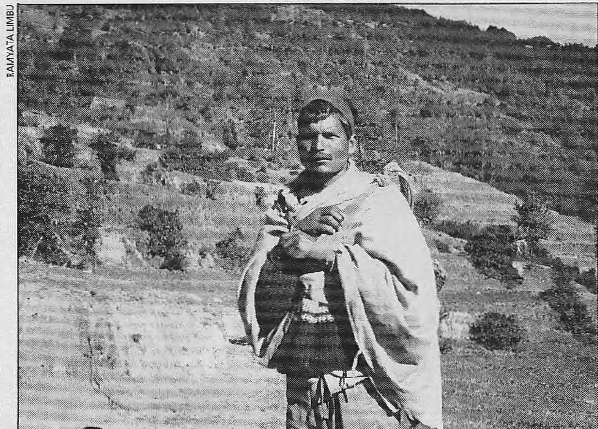

labour to Bangalore.

A Closing Valve

With the continuing flow of Nepali workers to the Indian market, which is already crowded with migrants from various parts of India, attitudes are changing towards Nepali labourers. Discussions with scholars and labour organisers make it clear that the Nepal´s socio-economic “safety valve”—which is the ability of hill peasants to pick up and move to the plains—may be closing. This means a building societal crisis within the Nepali state.

According to Mr Paudyal whose focus was Bombay, it is getting increasingly difficult for Nepalis to get jobs in the regulated sector, such as public institutions and industries. “This indicates that in coming days young migrants who lack education and occupational background, which is true for most Nepalis who come over, may not find jobs except under the poorest and least regulated conditions, dooming them to pauperism.”

In Bangalore, Ms Pfaff-Czarnecka found that the local population has begun to resent the fact that jobs were going to foreigners from afar. Besides, the reputation of the Bajhangis as steadfast and reliable was also under stress, as “increasingly, Bajhangis are becoming known as drunkards and gamblers”.

“Attitudes have changed towards Nepali workers over the past two decades,” concedes Mr K.C. of the Emigrant Nepali Association´s Delhi branch. When he arrived in Delhi from Baglung district in 1975, he had no difficulty finding a job as a guard at the Central Archaeological Library. “People only wanted to employ Nepalis then. Today, they think twice,” says Mr K.C., who is today a senior library assistant at the same institution.

“Yesterday´s Nepalis are different from today´s Nepalis, there is no doubt about that,” says Mr Bhandari of the ENA in Bangalore. “People have less confidence in us today, and while there will always be menial labour, the standard of jobs available to Nepalis is coming down. There are already so many uneducated unemployeds in India, how can illiterate Nepalis expect to get good jobs?”

According to Laxmi Prasad Upadhaya, also working in Bangalore, “Most Nepalis work in security, but now in every state, Indian ex-servicemen are opening security companies and supplying jobs on contract.” This contractor system has hit the migrants, says Mr Upadhaya, “With a contractor providing the guarantee, employers do not mind who is guarding their gates. Before, they would go only for Nepalis.”

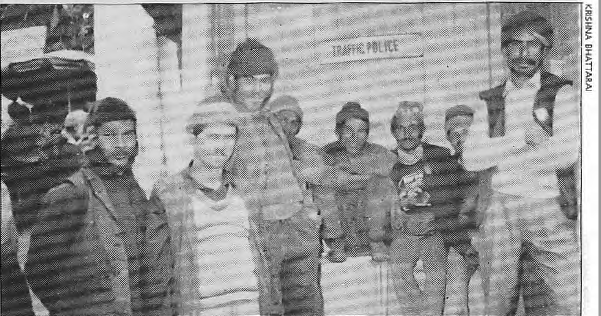

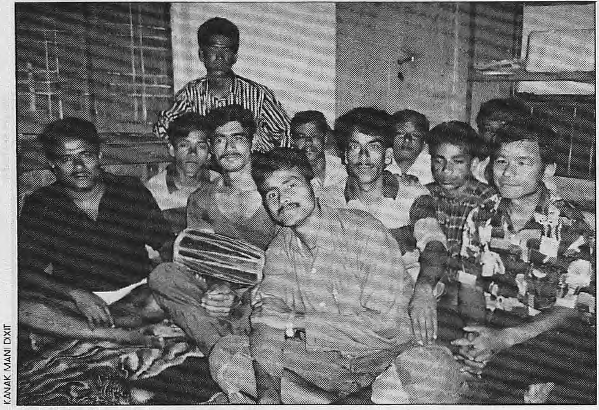

Association in their club room.

The notice issued by the New Delhi police in early 1996 after the highly publicised killings by servants, advising households against employing Nepali domestic help, is also suggestive. While there has been no specific study, the bad press received by the Nepali servant-class is bound to have had an impact in the job market. For many months in the first half of 1996, it is said, the party talk among New Delhi´s middle and upper-middle classes revolved around the need to be wary of Nepali manservants.

The possible impact of such negative publicity had some of the Nepali support groups knocking on the doors of the Nepali Embassy in New Delhi. “But what can the embassy do?” asks Ambassador Lok Raj Baral plaintively, when approached by a journalist. A political scientist who has himself studied the problems of migration and refugees in South Asia, Mr Baral could only say, “We are not a social organisation. We do not have the agenda or the funds to tackle such a huge problem.”

revocation of 1950 Indo-Nepal treaty and

guarantee of security for migrants.

That remark, indeed, epitomises the stance of the Nepali government and academia with regard to the national haemmorhage that the migration process represents. To begin with, there is little awareness or worry about the great exodus that has now become a trademark of the Nepali hills. Even among those who do know and understand the extent of the problem, as with Ambassador Baral in New Delhi, there is a helplessness and a lack of exertion.

Looking ahead, because the economy of Nepal seems nowhere near ´takeoff, it is clear that out-migration will continue. On the other hand, the space in India will be increasingly more constricted. As more destitute population groups within India, such as communities in Bihar, Bengal and Andhra, and the tribal populations from all over, clamour for those very menial positions that the hillmen have been manning till now, the job-openings for Nepalis will become restricted, or will be lowered to an even more menial level.

the Ghanaian embassy in New Delhi.

The Indian Northeast, which used to be a major employment destination for Nepalis of Nepal, is today out of bounds starting from the Assam-Bengal border. Even Sikkim, that Nepali-speakers haven, has slammed its doors on the Nepalis of Nepal. A special permit is required for Nepalis to work in the state and, in general, anyone who looks like he is of the labouring class, is turned back from the bridge at Rongpu, on the border between Sikkim and West Bengal.

Even the specific demand for the ´Gorkha´ to man the gates, it seems clear, will in future be filled by the Nepali-speaking citizens of India rather than the Nepal-born migrants. All in all, therefore, the economic wellbeing of the migrants from Nepal, and by that token the situation of families back home, is bound to dip rather than rise in the years to come.

As the shine of the “honest bahadur” wears off, as other plains communities begin to take the place of Nepalis in the job market, and as the geopolitical differentiation between Nepalis of Nepal and Nepali-speaking citizens of India becomes sharpened, the window which the plains labour market represents is beginning to swing shut. As the process builds, it will hit the hill communities of Nepal like a long-drawn economic thunderclap.

Says Mr Upadhaya, of Bangalore, “The job opportunities here are becoming constricted, meanwhile the economy of Nepal is still stagnating. The´ Kathmandu politicians should be made aware that we may be kicked out, then what do we do? We keep asking the sashaks (in Nepal), what will happen if all Nepalis working in India are pushed back and there is no work in Nepal?”

two decades.

The answer, and there is only one, is for the Nepali state to become serious, rather late in the century, about genuine development of the hinterland. A beginning will have been made if, at long last, the Kathmandu intelligentsia—the professor and the politician, the bureaucrat and the social activist—at least recognises that there is a problem of migration and survivability out in the hills.

That, and an effort to do something about it.

–G. Khatri is with the Sri Sagarmatha daily, R. Limbu is a reporter for The Asian Age and S. Lama is with the Nepali-language Himal magazine. All are Kathmandu-based.

Bahadur = Kancha = Gorkha

“Pahilay ijjat thiyo, ahilay chhaina (Before we had respect, now we do not),” says Mohan Bahadur Kunwar, from Bajhang District, who guards the Raj Mohan Villas housing development in Bangalore. He has been here for more than five years, and earns 2700 rupees a month, whereas his relation Ram Bahadur Kunwar, just arrived, earns a thousand a month.

Dandapani Sapkota is just next door to where the Kunwars work. He is from Foksing village in Gulmi District and has worked in the city for 17 years as a house-servant. He says he is tired, and would not recommend his kind of work to anybody. “I save about 12,000 to 15,000 rupees a year, but this is not good nokari (service). The starting salary is one thousand a month, without food. I earn 2200 rupees, but it should have been 4000 by now.”

“Fully 99 percent of Nepalis in India are in menial jobs,” says C P Mainali, senior Left politician in Nepal, who worked for three years organising migrants in India. “Only one percent might be in technical or skilled fields, and less than 0.1 percent will have an independent income. There is not a paan shop in the name of a Nepali in India, and, less than one in a thousand is a clerk.”

Says Sudarshan Karki, Delhi City Committee Secretary of the All India Nepali Unity Society, “The situation of the Nepalis is tenuous. Those with good jobs may earn 2000 rupees, but more are earning 200 rupees. They are on call 24 hours a day, the lucky ones may be for only 12.”

Manager Pande, professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, says, “It is fashionable to have Nepali chowkidaars, for the sense of security it provides. The ultimate status symbol is to have a little bungalow and a bahadur standing guard at the gate.”

According to journalist Kuldip Nayar, “This tradition of treating Nepalis as synonymous with bahadur and kancha must be done away with. Nepalis are capable of more than merely working as guards and houseboys.”

Shopkeeper Ganesh Das Agarwal of Benaras, proprietor of the Saree Karobar Kendra, admits that he does not have Nepali workers, and adds, “But if I get them I will keep them. A business, a Maruti car and a Nepali chowkidaar, that is what we all want.”

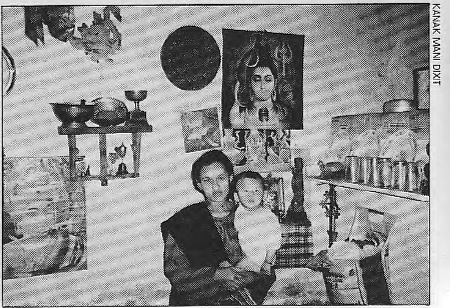

“Wherever there is hardship, you will find Nepalis,” says Krishnamaya Bohara, preparing her morning meal outside her one-room shanty in Nepali Camp in New Delhi’s Vasant Vihar locality. There are altogether 180 shanties (or jhuggies) in Nepali Camp.

Kumar Kancha is the son of Nepali migrants working in Calcutta. As a boy, he went to Bombay to try his luck in tinseltown. Before he rose to recognition as a playback singer for Hindi films, he survived as part of Bombay´s underclass, graduating from restaurant boy to street tough. The singer says lack of ambition is the greatest failing of the mostly illiterate migrants. “Dukhha la painchha ni (Of course one suffers), but you have to want to get out of your situation. We Nepalis tend to be satisfied with one little job, whereas the Gujaratis, Bengalis or Biharis are very entrepreneurial. Today, he might be a darban, but before long he is selling peanuts on the pavement, and the next thing you know he owns a fruit stall.”

Kumar Kancha says he has deliberately maintained his surname as ´Kancha´ (meaning “little boy”) in professional life. “I insist on Kancha even though my friends have suggested I discard it because of the negative association it has in India. They say it will not help my career, but I will keep the name because I want to prove that the kancha not only washes dishes and stands guard, but he can also be a professional and compete. I want to change the very connotation of the word, which is so denigrating of Nepalis and speaks of our condition in India.”

Gorakhpur Piranhas

One of the greatest sources of distress for Nepali migrants is the exploitation they face on the way back home on the rare holiday. Says Prem Bahadur Kunwar of Bajhang, a guard in a Marine Drive high-rise in Bombay: “We have to face a lot of atyachar (exploitation) all the way to the border. On the tram and on railway platforms, police and goondas give us trouble starting from as far away as Jhansi all the way to Gorakhpur and the Sunauli border point.”

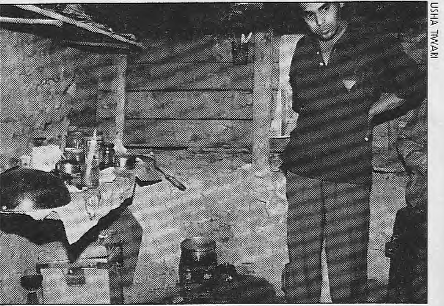

Photo: Usha Tiwari

Everyone knows that the Nepalis are returning home with their savings, and that they are aliens without much support while in transit through India. This provides the opportunity for the piranhas to accost the migrants and extort money.

According to Mr Laxmi Prasad Upadhaya, who works in Bangalore, “Gorakhpur is the worst place, where practically everyone, including the railway staff, the police, the CBI and local goondas shake us for money. It is really a tragedy that we cannot even go home with happiness and anticipation, for we know the trouble that awaits.”

The leaders of the Emigrant Nepali Association say their party leader Man Mohan Adhikari did raise this matter with the Indian side during his official visit to India in 1995 as Prime Minister. However, the harassment on the ground at Gorakhpur continues.