From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 3 (MAR 2007)

Everybody welcomes the idea of a Southasian University; it’s like mother’s milk. But even mother’s milk has to have the proper nutrients, or the baby will grow up malformed. The idea of a Southasian University is so overwhelmingly important that it must not be wasted at the altar of good intentions or individual ambition.

The very evolution of Southasia can be given direction by a Southasian University with practical, achievable goals and staying power. India’s support for such a venture is critical, as it would be able to provide significant funds and faculty, and hopefully would have the circumspection not to smother the institution in India-centrism.

Manmohan Singh, in his speech at the Dhaka SAARC Summit on 12 November 2005, said that he would push for a Southasian University as a “centre of excellence”. Said the prime minister: “We can certainly host this institution, but are equally prepared to cooperate in creating a suitable venue in any other member country.”

It is said that Prime Minister Singh has committed USD 100 million to the idea, which is good of him. It now appears likely that the idea will see fruition at the upcoming SAARC Summit in New Delhi in early April. Unfortunately, what is currently known of the project does not inspire confidence. Pushed by the Dhaka-born scholar and international administrator Gowher Rizvi, the plan is to develop a centralised institution with “a single campus … working under the direction of a single president/chancellor and academic council”.

The proposed campus would be set up on a hundred acres in Dwarka – now practically a New Delhi suburb – which would attract scholars-in-residence and a Southasia-wide student body. The placement is already problematic. The first university of Southasia must be one that promotes a regional vision quite distinct from the capital-centric model of the SAARC organisation. As such, the university needs to be physically removed from any capital, in particular the region’s most powerful one.

Fortunately, decentralised models have been developed, including by a team headed by Rizvi’s compatriot, the political scientist Imtiaz Ahmed. The money that India seeks to invest in the Southasian University, together with contributions by other SAARC members according to GDP, could instead be made available to a Southasian University Grant Commission, constituted of top-notch academics and administrators from the region’s countries. Such a commission could well be headquartered in New Delhi, but its core activity would be to detect, fund and monitor universities across the region. The commission would remain independent of national interests, not compromise on tokenism, and to institute stringent reporting requirements of the grantee institutions.

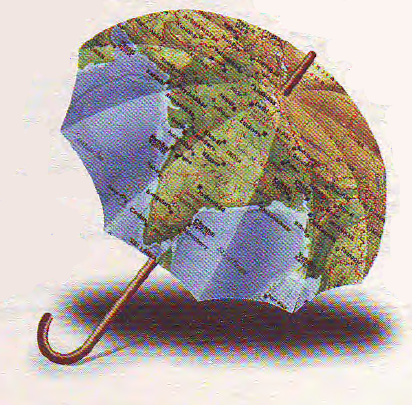

At least to start with, the Southasian University would not be a campus but an umbrella institution. It would provide support to select post-graduate departments in, say, JNU and Delhi University, Jadavpur University in Calcutta, LUMS in Lahore, Benaras Hindu University, Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, the universities of Dhaka, Karachi, Colombo and Madras, and so on. Many of these institutions delivered Southasia its intellectual stalwarts, the nation-builders of the modern era; now, most have deteriorated due to political interference and lack of endowment. It is important to revive these hallowed universities, rather than to build a spanking new one that would only further suck away energy and dynamism from existing institutions.

A lack of social-science learning has robbed Southasian society of an upright intelligentsia amidst dislocating modernisation and globalising regionalism. As such, it is important for the proposed university to make attractive once again post-graduate courses in history, political science, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, as well as education, public health, and science and technology. Those studies supported by the private-sector – information technology, medicine, engineering, business management – should be left out by the planners of the new institution.

A Southasian University should be one that germinates and grows along with the multi-layered understanding of regionalism amongst our societies. It should not be an institution mandated from on high. Nor should the new university be a cyber-institution that floats in midair without ownership of its constituent units, which would be a danger. The departments and faculties under the Grant Commission must be proud of being part of the Southasian University network.

We must get the Southasian University right the first time around, because the costs of failure would be high. Manmohan Singh is a thinking Southasian; may he back the right idea.