From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 5 (MAY 2007)

Autumn of 1977. A 22-year-old studying law in Delhi University took the Wagah-Attari route – then a series of super-fast dilapidated buses – through Lahore, Peshawar, Khyber and Jalalabad, to arrive in breathtaking Kabul. Coming from license-raj India, Kabul was as close to the ‘West’ as was possible in those days. The markets were stocked with Western goods, Russian and German cars ran on Chicken Street, and socialist architecture was just hitting its stride.

Back then, Kabul shocked the young man from Kathmandu, with all its schoolgirls in skirts showing a lot of leg. Out in Hazara country, the Big Buddha in Bamiyan was still standing, and it was possible to climb up the tunnels to look down on his humongous, 1500-year-old torso. All of that, of course, was subsequently blasted out of existence in an unparalleled act of desecration.

In 1977, the king had been deposed, and Sardar Mohammed Daoud Khan was in power. This was Kabul before the Russian invasion, the rise of the Taliban, the hanging of Najibullah, and the devastation wrought by the warlords after the Talibs were routed post-11 September 2001. Bullets and howitzer shells would soon find their mark in every single downtown building; even Babar’s modest resting place would take a hit.

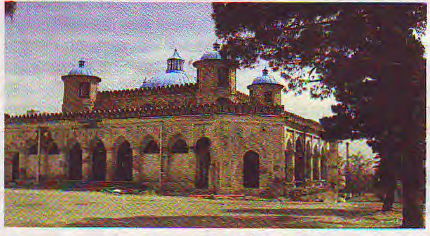

Back in 1977, on a pine-covered ridged above Kabul, the summer residence of Afghan royalty had been converted into a haute restaurant. Like everything else, 30 years later it is a shell of a building (see photo), with peeling plaster, furniture all gone, and an empty swimming pool in which local lads play football. Some day, when Kabul has made headway on its long journey back to normalcy, and the Talibs and Mujahideen are both gentrified, this place will regain its old character.

There is evidently a lot of money being made in Kabul today. The elite have certainly been enjoying the war economy, while the warlords in their ‘narco mansions’ make their millions now that Afghanistan is a monopoly producer of heroin and cocaine. But neither the war nor the narcotics economy are evident on the streets, where the commoner hopes that one more year without the Taliban’s threatened incursion will allow the economy to find itself. Kabulwallahs generally seem to be rooting for the success of NATO’s ‘ISAF’ force, thought to be more effective than the American Marines.

The stamp of international donors is everywhere, on even the most modest of projects. Public buses are to be found plastered with Japanese or Pakistani flags. Over by TV Hill, one even spotted a ‘UNDP Public Toilet’. Only the Indians, who are providing massive amounts of aid – including 500 buses and the spanking-new Parliament building coming up on Darulaman Boulevard (which lost all its trees to shelling after 1993) – seem to be confident enough in their relationships with President Karzai and the Dari-speaking elite to be discreet in their munificence. But the taxi drivers of Kabul all speak Bollywood Hindostani, and sport the most current Bombay patois.

Kabul today has electricity for four hours a day, so all the well-to-do have generators. Down on street level, Nepali guards are well paid to suffer at the front lines of all expatriate offices, military and donor alike. They seem to be the ones doing the dying, as and when required. The new phenomenon here are the suicide bombers, euphemistically called ‘anti-government elements’. In late March, three people were killed in a suicide blast near the zoo; the following day, life was back to normal on the spot which still sported a patch on the ground.

Another to have lost his life in Afghanistan’s turmoil – this time in an al-Qaeda assassination, two days before the attacks of 11 September 2001 – was Ahmad Shah Massoud, the Lion of Panjshir. Today, Massoud’s portraits are ubiquitous in Kabul, in order to keep the Panjshiris happy with having no berth in the current cabinet. Massoud’s brother in law, the dapper former Foreign Minister Abdullah Abdullah, today lives in New Delhi, perhaps on the green boulevard named for Massoud in early April.

A couple of days after the suicide blast at the zoo, Hamid Karzai went to Delhi to attend the SAARC Summit. Welcome to Southasia, Afghanistan.