From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 7 (JUL 2007)

When trekking in the hills of Southasia with a load on one’s back, the mind is concentrated and the eyes are fixed on the ground. The satisfaction of walking alone – carrying a load, though one not too heavy – is probably linked to human evolution, as the kind of activity our ancestors did in the long march from monkey to man. One might even hazard that some aspect of hiking alone is written into the human genetic code. Herein lies the attraction of trekking as a recreational activity, into which it has evolved since the 1970s.

Trek is actually a Boer/Dutch term that was imported into the Nepali Himalaya after some pioneering tourism entrepreneurs realised that there was no English word to describe this type of walking. This was neither camping nor hiking, but a special kind of walking on trails used by villagers who have done so – and have carried loads on their backs with the help of a forehead strap, also called namlo – for millennia.

Trekking sharpens the mind, especially after the body finds its pace, breathing becomes regular, and the heart pumps harder to supply the oxygen demanded by the lungs to feed the muscles. In the process, the brain gets a bonus dose of well-oxygenated blood.

Even when in a trekking group, the actual walking is an individual exercise, with each trekker in his or her own world. The mind is free to roam, to be imaginative, to think, plan, devise. Many more ideas are born during a strenuous walk than sitting sedentary on a settee. A study of how inventions come to be, or how flashes of inspiration are generated, would probably show that the origins lie not in seminar halls or in cross-legged meditation, but on walks or rambles. (An aside: Himal magazine was born in the mind of one trekker during the summer of 1986.)

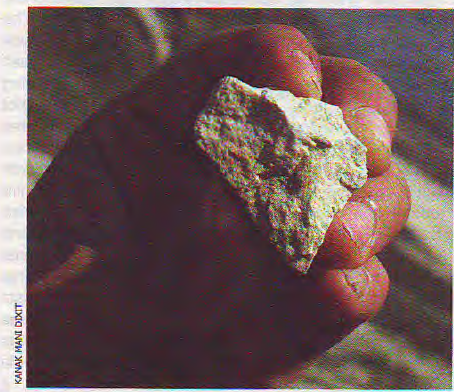

The brain can, of course, also go awry when it is receiving a surge of blood, and creativity can tilt towards the impractical, if not the downright absurd. Speaking of which, over years of trekking, with the eye fixed on the ground and a pack on the back, I have found that rocks and pebbles often take the sudden shape of – Southasia! The shape of the Subcontinent constantly jumps up at me from the pieces of stone along the trail.

During a trek in the Langtang region north of Kathmandu in early June, I tried to divert the mind’s advanced creativity to decipher this phenomenon. Why do I tend to see Subcontinental shapes everywhere I turn, with the outline of the African continent coming a distant second? Of course, I stand to be directed by the reader on something that a few – at least one or two – might consider worthy of weighty consideration.

This seems to be a matter to be discussed between a geologist and a psychologist (and perhaps, in the case of this columnist, a psychiatrist). The geologist might suggest that the crystallochemical structure of certain rocks naturally promotes a chipping or breaking at the distinctive 60-degree angle that defines peninsular India, between the Coromandel Coast and the Bay of Bengal shoreline. Or s/he might point outs that rocks break all the time in all different directions – not limited, of course, to the two dimensions that give us a Southasian shape. This is where the psychologist butts in, to say that, among the plethora of forms of broken rocks to be found in nature and along walking trails, the mind’s eye will search out the shape(s) that come(s) closest to what one is familiar with. Essentially, you see what you want to see, and not what you don’t.

And so, when the mind is excessively creative during a trek, what else would the Southasian editor notice while heaving his backpack up the Langtang Valley, but Subcontinental forms everywhere? Someone else may see that of Mahatma Gandhi, or, more likely, that of Aishwarya Rai.

Moral of the story: If you want to commune with your ancestors, go on a trek. Do the same if you want to see things that are not there, or shapes that come jumping at you with a certitude that defies geology. Alternatively, too, if you want to start a magazine, do a trek.