From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 12 (DEC 2007)

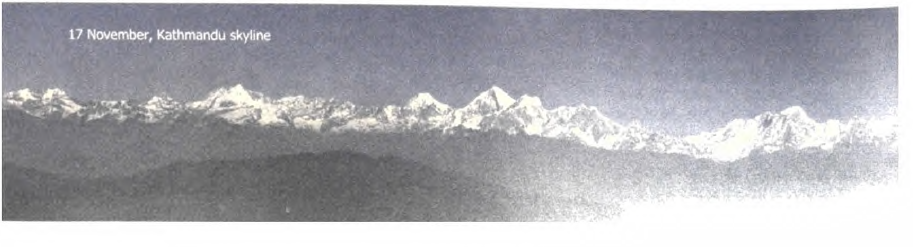

On 15-16-17 November, the citizens of Kathmandu woke up to three brilliant mornings, with the Himalaya visible crisp and clear – a 300-km horizon of himals on whose snowline, if your lookout were high enough, you could see the curvature of the earth. There was none of the localised smog, nor any of the all-pervading haze that seems to have become a signature of the central Himalaya of late – dust particles transported by westerlies from the plains of India and Pakistan.

Three brilliant days, which followed one after another – and which the tourism industry saw as a boon and a bonus. After the Maoist Doldrums, that industry needs everything available right now to boost its industry, and the clear skies and brilliant views were good for business.

But while Kathmandu was basking in the winter sunshine, southern Bangladesh was reeling under the attack of Cyclone Sidr. The cruel irony of it all was that the clear skies of Nepal were the direct meteorological result of Sidr. As Bangladesh fisherfolk and peasantry alike were being slammed by 250-kph winds, the circulation of air currents that fed the cyclone sucked in air from as far away as Central Asia and the Tibetan plateau. This is what brought the clear northern air to Kathmandu, and is why the tourists were smiling even as thousands died and millions were affected by Sidr.

The varying impact of natural and manmade phenomena is rarely so starkly visible as in this case. Other than some momentary clouds over the southeastern tip of Nepal, the country and its population were blithely unaware of all the havoc being wreaked over by the bay.

When nature devastates one region and favours another, one is likely to take it as an act of god. But it is what we ourselves are doing to the weather, through manmade interventions, that needs watching out for – especially now that global warming is a proven phenomenon, despite more than a decade of foot-dragging by a good part of the scientific and political community. That decade can now be seen as a massively wasted opportunity, and the alarm of the kind we hear today would have done better if heeded back in 1990, if not 1980.

Here in Southasia, we are going to get hit by global warming right between the eyes – even while our burgeoning middle class seeks to add to that process in its quest for all of the energy-guzzling creature comforts that the West has taught us to desire. There will be a time lag between what science tells us and the ability of the politicians to restrain their populaces from jumping onto the consumerist bandwagon. And so, no one will be able to stop production on the one-lakh-rupee car that the Tatas are announcing. And everyone will want to fly if they can do so, and spew more warmth into the atmosphere. And how dare the West ask us to forbear?

Of course, climate change will hit Bangladesh more than the rest of us in Southasia. An inch, two inches, six inches rise to the ocean due to global warming will lead to inundation and out-migration. The rest of us had better be prepared. What an irony, that a country that has learned to save its millions from cyclones through early warning and a network of elevated shelters – both of which led to the relatively limited deaths in late November – and one that has so persevered in recent years to uplift its masses, will now fall prey to the rising waves.

Bangladesh will be slowly strangulated, and that is when the true underpinnings of ‘Southasianess’ will become evident, if it truly exists. When the people of the delta are forced to migrate out, will the rest of Southasia be welcoming? In the evolving era of rigid frontiers and nationalist populism, the suffering of the people will be immense. What is to be done? Anything less than a clear appreciation of the situation will lead to humanitarian disaster followed by political disaster.

Can we look that far ahead? Let us at least lay out the scenario: that rising sea levels will lead to millions of livelihoods lost in the Padma-Jamuna (Ganga-Brahmaputra) delta, leading to a mass exodus. Will the rest of Southasia accept the migrants? If this is the civilisational Southasia about which we like to talk, then it must do so, and it must ready itself to do so. If we cannot accept this proposal, then we will have failed the test of Southasianess.