From Nepali Times, (18 Aug, 2021)

Kathmandu and Kabul are far apart, but the two countries share some difficult history

Even though Nepal and Afghanistan are separated geographically, Nepali and Pashtun warriors have met face-to-face over more than 200 years. While the Pashtun were in their home territory, the Nepalis were fronting for others, and now with the Taliban’s second-time total victory in Afghanistan, new dynamics will have to evolve.

As current chair of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Nepal must take the lead in, on the one hand, helping the world accept the fait accompli of the Taliban victory, while on the other get the didactic, xenophobic Taliban to accept the values of pluralism and multilateralism. As a country which holds these values dear, Nepal should reach out of its own cocoon to do what it can.

The history of Afghan-Nepal relations goes back two centuries, with what the British colonisers called the ‘First Afghan War’ and continued through the ‘Third Afghan War’ against the Pashtun in 1919. These were Britain’s wars in Afghanistan, and the Nepalis who joined at various times were straight-off mercenaries, parts of the British Gurkhas, and even the national Nepali army. Most recently, British Gurkhas were fielded as part of the ISAF/NATO force, or were recruited by western military contractors to guard Western bases and embassies.

The Army of the Indus

Nepal is situated in the mid-Himalaya, while Afghanistan sits astride the Pamir and Hindu Kush, 2,000km away. Even at its height, the expansionist Gorkha Empire could not go beyond the Sutlej River. But these are the only two countries in South Asia that fought off colonialism. Afghans are known for their fierce resistance to foreign hegemony, as were Nepalis, but Afghanistan has nevertheless been serving continuously as a ‘fighting field’ for outsiders, while at best Nepal has been a ‘playing field’.

Historically, there were indirect links between the central Himalaya and the Hindu Kush/Pamir: from the ancient Aryans down to the Moghuls, it was through the Khyber Pass and other northwestern passages that migrations and conquests of the Indus-Ganges plains occurred. Afghanistan stretched outside the country’s modern boundary, and included the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa region of present-day Pakistan.

It was the colonial British that separated the Pashtun people with a new boundary called the ‘Durand Line’. This forced demarcation has relevance today because, while Afghanistan is ethnically diverse with Kyrgyz, Baloch, Hazara, Uzbek and other communities, the Taliban leadership and rank-and-file are dominated by Pashtuns.

Even though Afghanistan and Nepal were spared colonial rule, Afghanistan suffered much more foreign interference than Nepal. Located between Czarist Russia, Central Asia and the British Empire and with Persia to the west, Afghanistan was (and remains) a strategic prize. Nepal, on the other hand, was protected by malarial jungles to the south and the world’s highest mountains to the north, and neighbouring powers found it more advantageous to maintain it as a buffer state.

When the Gorkha Empire felt threatened by the East India Company in the mid-1700s, it sent feelers for help to the Maratha and Sikh kings. Though probable, we do not have historical evidence to indicate that Kathmandu also appealed to the rulers in Kabul.

Meanwhile, even before the end of the Anglo-Nepal war of 1814-1816, some Nepali soldiers had already gone over to the British side, marking the beginnings of the ‘Gurkha’ brigades. After the bloody defeat at Nalapani, the Gorkhali general Bal Bhadra Kunwar escaped to join the forces of Sikh king Ranjit Singh in Lahore. The Nepali word लाहुरे for soldiers and workers who go abroad is derived from the name of this city.

We do not know what happened to the other Gorkhali troops who went with him, but Bal Bhadra himself was killed in battle when the Sikhs were fighting the Pasthuns in Naushera, which was then Afghan territory.

There are other indirect Afghan influences in Nepal. The words रुपियाँ and अशर्फी were introduced in India by Sher Shah Suri, who became ruler of Mughlan after briefly ousting emperor Humayun from Delhi. The terms percolated up to Nepal. Although Sher Shah was born in Bihar state bordering Nepal, his ancestral village was Sur in the Sulaiman Range, within Afghan territory.

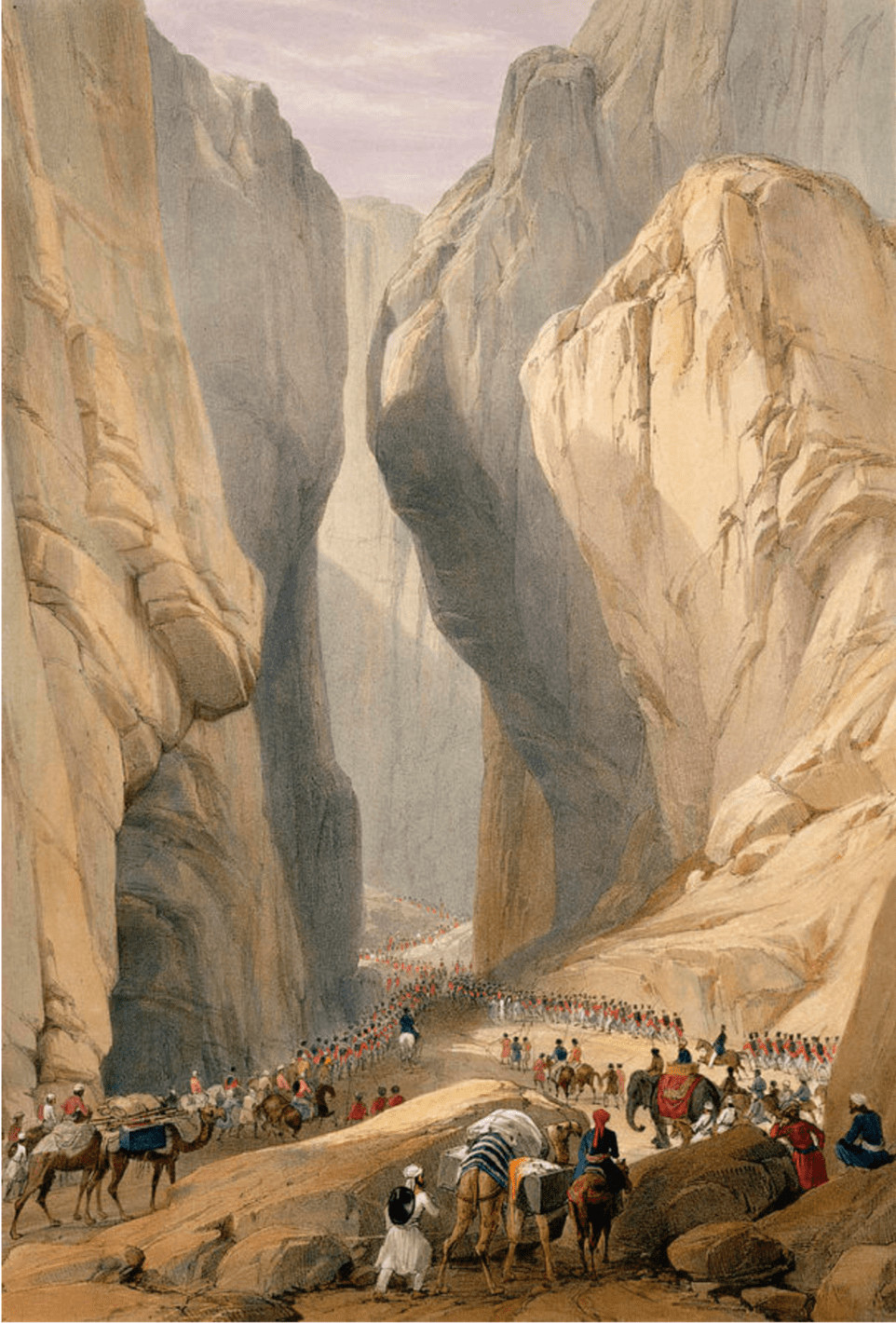

Nepalis and Pashtuns came into more direct contact during the East India Company’s Afghan Campaign of 1839-42 when an ‘Army of the Indus’ was assembled to invade Afghanistan. This was part of the Great Game, when British India felt it had to contain the expansion of Czarist Russia. Thousands of troops from the early ‘Gurkha’ units were deployed on the Afghan front, and as was the practice in those days, the soldiers were accompanied by camp followers which included their wives and children.

The ‘Army of the Indus’ was routed, and legend has it that only one British officer straggled out to Peshawar, though there would have been a few more. There is no count of how many Nepalis were cut down with swords in Herat, Ghazni and Kabul, or those who froze to death in the dreadful Afghan winter. Many women and children would have been enslaved by Afghan warlords.

North of Kabul in Charikar Fort, hundreds Gorkhali fighters were under siege for months, with the water source blocked. When the Gorkhalis tried to break out, most were killed, except a sipahi named Motiram who managed a dangerous and arduous trek down to his cantonment in the Punjab plains to tell the tale.

Najibullah to Ghani

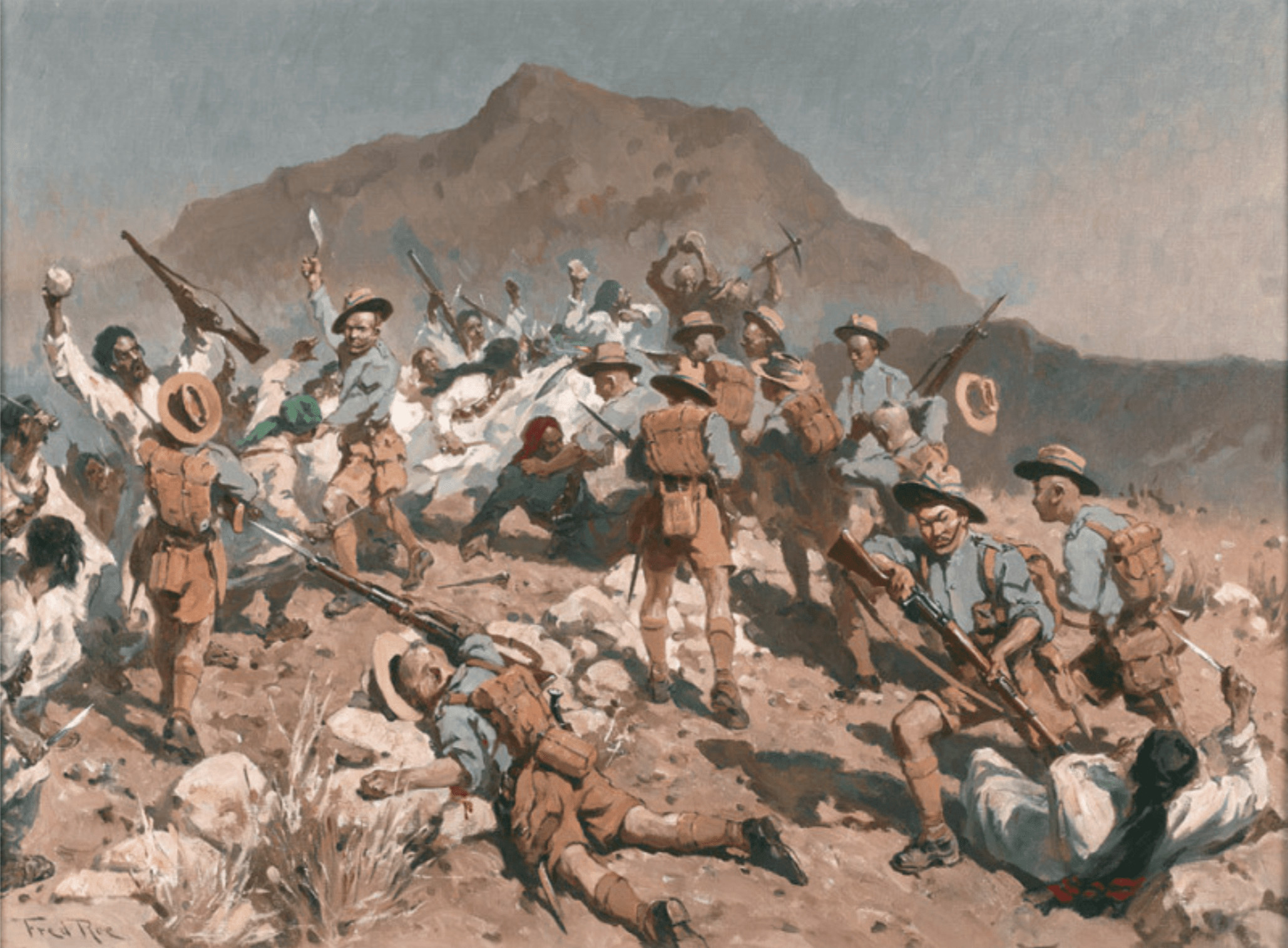

Throughout the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, Nepalis kept going back to Afghanistan – to fight. Gurkha soldiers assigned to the Durand Line engaged in frequent skirmishes with Pashtun fighters. And in 1919, while other Nepali soldiers were returning home from Belgium, France and Gallipoli, soldiers of the Nepal Army were sent to Afghanistan by Prime Minister Chandra Shumshere Rana to help the British counter a rebellion in Waziristan. Those troops for the ‘Third Afghan War’ were led by Gen Babar Sumshere.

In the modern era, the people of Afghanistan suffered as super-powers muscled their way in. In 1974, Afghan king Zahir Shah was overthrown, and at the end of the Mujahideen war that followed against Soviet occupation, President Najibullah was dragged out of the UN compound where he had sought refuge, tortured and hung at the gates of Kabul in 1996 by the Taliban.

Unable to face the resistance of Afghan guerrillas, the Soviet Union withdrew in 1989 and cast off Najibullah in 1991, just as the Americans abandoned Ashraf Ghani in 2021. During this whole time, Afghan polity was decimated as a result of interference by the Soviets, the Americans after 9/11, NATO forces, Pakistanis and Saudis, who together spent trillions of dollars.

While all that money landed up at the hands of the Afghan elite and warlords, ordinary Afghans died and suffered. Millions became refugees in Iran and Pakistan, and more refugees are streaming out as this is written – the desperation is seen in Afghan men trying to attach themselves to C-17s on the runway at Kabul Airport this week.

The irony of it all was that some of the descendants of the Gorkhali troops who fought in Helmand and Kabul nearly 200 years ago were back as part of the Gurkha units in the British deployment in the same places as a part of NATO’s ISAF mission. The blood and sweat they sacrificed seems to have been in vain, as President Ashraf Ghani flew out of Kabul on 15 August. Ghani said he wished to prevent bloodshed, and would doubtless have also feared meeting the same fate as Najibullah. But all this seems to have been part of a larger withdrawal deal worked out between the Americans and the Taliban in talks in Doha.

One of the consultants that the World Bank brought to Nepal in 2006 to advise leaders here about post-conflict rehabilitation was Ashraf Ghani himself. The author of the book Why States Fail, Ghani wrote in one of his columns for Nepali Times then: ‘Surely the people of Nepal deserve leadership from their politicians to ensure that Nepal embarks upon a path towards a new future. A new future is no longer a dream, it has become possible.’

Nepal has not been brutalised and ravaged by a series of proxy wars like Afghanistan has for the past four decades. It did suffer the violent 10-year internal conflict, but the peace process took hold, and the country held two elections to a Constituent Assembly that wrote the new Constitution. Afghanistan’s violence, the killing of innocents and religion-laced extremism, have been at a whole different level.

If it was soldiers that Nepal used to send to Afghanistan in the past two centuries, in the last two decades it was Nepali development experts, gender and media consultants and governance advisers who went to Kabul on behalf of the UN or other partners. And then there are the estimated 15,000 security guards protecting various embassies, hotels, bases and installations in Kabul. Nepali were attracted to dangerous work in Afghanistan because it paid much better, even though they were often hired as guards of the Western soldiers.

While some Nepalis are starting to return on repatriation flights this week, there are many stranded in Kabul and fearful about their future. The Nepal government must proactively establish contact with the new regime in Afghanistan in order to ensure the safety of its citizens there. It is also hoped that the soft language emanating from the Taliban victors, about allowing safe passage to all who seek to exit, reflects a genuine commitment.

Nepal is currently chair of SAARC, and it could use its tenure to bring Afghanistan back into the South Asian fold even as the Taliban go about establishing themselves. Kathmandu must strive to establish bilateral relations, while remaining outside sphere of Indian, Chinese, Pakistani, Saudi or Western interests there.

China and Russia have already made their moves to establish relations with the Taliban government. New Delhi has been stung by Ashraf Ghani’s downfall, given their steadfast support for him, while there seems to be some rejoicing in Islamabad. If Nepal takes a proactive diplomatic approach (in a manner that would be wholly new to it) Kathmandu could use its bilateral relations to usher a new era of peace in the region. For Nepal as a country that has been so insular in past two decades, that may seem a tall order, but some self-confidence in foreign policy can make it happen.

The immediate priority of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, however, is to ensure the security and repatriation of Nepalis presently in Kabul and across Afghanistan. Meanwhile, Nepali civil society members must reach out to their counterparts in Afghanistan and offer safe haven should it be required.

While the Taliban spokesman has said all are safe, there is no saying when Afghan journalists, gender and human rights activists may not need support and refuge. Afghanistan is the only country in South Asia whose nationals must get a visa to come to Nepal. In the name of South Asian solidarity, ‘visa on arrival’ should now also be available for Afghan citizens.

The Taliban has been using Sharia law to justify its extreme form of patriarchy to prevent women and girls from equal rights, agency and education. It has also been violently suppressing minorities like the Shi’a and Hazara. The group that blew up the historical statue of the Buddha in Bamiyan in 2001 is now ruling Afghanistan, and there are genuine fears that the Taliban will return to its old ways.

The fact that the Taliban is in control in Kabul is a fait accompli. Nepal must accept this and, while working to extricate its citizens from Afghanistan, must help Kabul rejoin the South Asian sphere.