From The Kathmandu Post (27 February, 2015)

The reconstruction of a 17th Century temple in Patan is more than an exercise in architectural preservation

In 1669, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb ordered the destruction of the Kashi Vishwanath temple. Over across the expanse of the north Ganga plains, up in the Himalayan midhills, this act of desecration left the citizenry of Patan bereft. Where were they to go in order to worship Bisweshwar, the ‘lord of the universe’ visage of Shiva?

Enter Bhagirath Bhaiya, hailing from Pharping on the southern reaches of the Kathmandu Valley. A soldier, administrator, and philanthropist, he had risen to be the trusted chautara (prime minister) of Srinivas Malla, king of Patan. Bhagirath Bhaiya stepped forward to build the substitute for Kashi Vishwanath, including a replica of the giant Shiva lingam. The temple was consecrated in 1678.

For 256 years, the lingam in the temple at the south-west corner of what is today Patan Durbar Square continued to receive devotees of Patan and other parts. Then came the Great Earthquake that struck in the early afternoon of January 15, 1934. All of the Patan Darbar structures fell, including Bhaidegah.

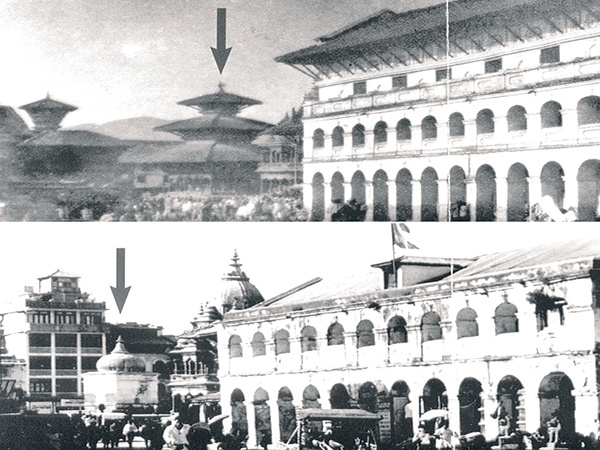

Rana Prime Minister Juddha Shumsher organised a herculean rebuilding exercise, and most of the temples of Patan Durbar were rebuilt, but not the three-tiered Bhaidegah. A ‘Mughal style’ domed room in stucco was built to house the sanctum.

It was to be another 81 years, Thursday, February 26, 2015 to be exact, before work was begun to give the temple back its original shape. It was a rainy day, yesterday, when the ‘kshyama puja’ was conducted. After the prayers asking forgiveness for the dislocation, the celebrated cultural historian Satya Mohan Joshi declared a symbolic start to the reconstruction using a hammer and chisel on the lime plaster.

Urban renewal

Since 2011, a group of citizens led by Satya Mohanji as its patron has been seeking to restore Bhaidegah to its original form.

The goal is at once to restore a place of living religious heritage, promote architectural preservation, give impetus to other preservation works on tangible and intangible heritage, and support urban cultural/economic renewal of the Valley’s inner cities.

The Cultural Heritage Preservation Group (of which this writer is a member) seeks to restore Patan Durbar Square’s architectural integrity while re-linking devotees to the historical temple, which has been attended to by a lineage of Maithili Brahmin pujaris. The urban renewal aspect of the reconstruction is crucial—and with the Durbar Square skyline reverting to what it was three-and-half centuries ago, the work will also boost tourism in and around this well-visited precinct.

The Group’s focus is to ensure that the work is done according to the dictates of tradition and the principles of conservation architecture as they relate to living heritage. First and foremost, questions had to be answered to the satisfaction of Unesco in Paris, because the Patan Durbar Monument Zone is a World Heritage Site.

The two underlying arguments for the reconstruction were that one, the Bhaidegah temple is part of a culture of devotion continuously practiced to this day, and, two, the absence of the three-tiered temple undercuts the historical integrity of the Monument Zone.

Conducting a ‘historical impact assessment’ of the Bhaidegah renewal programme, on October 22, 2014, Unesco’s technical committee gave its concurrence. In a letter to the Department of Archaeology (DOA), it recalled that “the lost Bhaidegah Temple was a major element of the Patan Durbar Square ensemble” and that the plans as presented constituted a “clear and carefully constructed document that sets out fully the justification for reconstruction”. On January 4, 2015, the DOA itself gave the go-ahead to the Group to proceed “according to the designs submitted”.

Struts and sanctum

It was important to try to make the reconstruction exemplary and so, the effort brought together architectural conservation experts, pundits, scholars, community leaders, philanthropists, and international supporters.

The work of the archivists was paramount and research delivered photographs taken in the 1920s showing the great eaves of the original Bhaidegah. Also located was a fine watercolour by Henry Ambrose Oldfield, doctor in the British residency during the time of Jung Bahadur, providing exquisite details of the woodwork on Bhaidegah—intricately carved struts, panels, and pillars.

As exciting was the discovery of the 17 struts and pillars in the Bhandarkhal stores of the Patan Durbar, some of them 14 feet long. Some of the struts have the names of the original benefactors etched on the wood. These struts were confirmed to be from Bhaidegah by comparing them with the Oldfield painting.

Despite the power of the earthquake which brought the temple crashing, the broad plinth of Bhaidegah is intact and the lingam in the sanctum is undamaged, though the Nandi bull standing outside seems to have been hit by falling debris back then. The temple still has its original brass finial (gajur) on top of the stucco structure and restored, it will crown the reconstructed temple as well.

The greatest challenge has been finding the kind of load-bearing Sal wood (shorea robusta) required for the reconstruction, both because of the girth of the required members and the escalated cost of the material. That challenge was met, with support from the philanthropist Prithvi Bahadur Pandey, the Norwegian Embassy, and Patan Sub-Metropolitan City, and master craftsmen have been working over the past year in workshops in Bungamati and Bhaktapur to carve the pillars and panels. Experts in Hindu iconography have provided their input on motifs as well as the placement of deities and symbols.

Who was Bhagirath?

The Bhaidegah reconstruction will mean a lot of things to a lot of people but for this writer, it is above all a tribute to the historical personality of Bhagirath Bhaiya, the commoner from Pharping who rose to power and prestige in Patan (Yala, Lalitpur). The rebuilding work over the next two to three years is an opportunity to highlight the rich and textured urban history of Kathmandu Valley, including the personalities of the past.

Bhagirath Bhaiya was known for his fighting prowess and as general, he fought for Patan in Makwanpur and elsewhere. King Srinivas Malla, in an inscription, asked the public “to make no distinction between him and me”. He was known for land grants, building works, and temple repairs in both Patan and Pharping. For the inauguration of Bhaidegah, Bhagirath Bhaiya built the long pavilion (Laampati, across the Mangal Bazaar road) to seat the 12 potentates who attended, including from Kathmandu (Ye), Bhaktapur (Khopa), and as far afield as Tanahu.

There are several inscriptions left behind by Bhagirath Bhaiya that indicate the scope of his societal consciousness. One inscription in Machhendra Bahal reads, “Kings should not needlessly torment the people. If that happens, the people have a right to lodge complaints and ministers have a duty to present them before the king.”

His reaction to the destruction of Kashi Vishwanath in Benaras was typical—put up a Bisweshwar temple right here in the Valley. Scholars believe this was the first such temple built anywhere in the Subcontinent after the desecration in Benaras, after which many came up in other parts.

Bhagirath Bhaiya’s end came at the hand of King Yognarendra Malla, who usurped the throne from his father Srinavas and had the chautara killed. Bhagirath Bhaiya is long gone, but I would like to believe that he still watches over us. The reconstruction of Bhaidegah is first and foremost a tribute to this historical commoner from the Kathmandu Valley.