From Himal Southasian, Volume 20, Number 10/11 (OCT/NOV 2007)

The very party that injected the Constituent Assembly into the Nepali national agenda has now developed cold feet. Postponement of the 22 November elections for the Assembly would create a nation-wide crisis of confidence, but the political process must be kept within control of the eight-party alliance, including the CPN (Maoist).

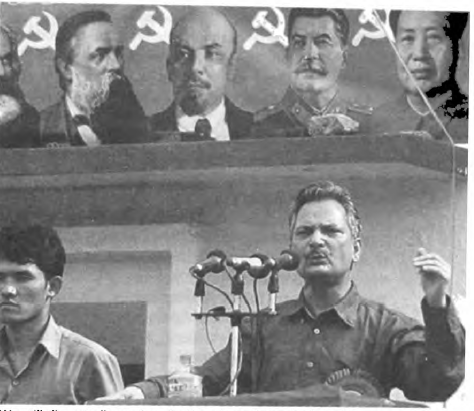

ideologue of the CPN (Maoist), Baburam Bhattarai, at the party’s

18 September mass meeting

When, in April 2006, the people of Nepal overthrew the ambitious but incapable king, Gyanendra, they mandated the country’s political parties and the Maoists to work for peace and democracy. This was to be done through a Constituent Assembly, which would eventually draft the new law of the land. The Maoists, who had peacefully supported the People’s Movement, emerged to join the seven parliamentary parties, signing a Comprehensive Peace Accord in November 2006. In so doing, they formally gave up their ‘people’s war’, launched in February 1996. In January 2007, they joined in the promulgation of an interim constitution, and rode the momentum to enter the interim parliament with the same number of seats in the house as the two largest parties, the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist). The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) also joined the interim government with five cabinet berths. As such, the stage was set for the greatest prize of all for the people of Nepal: elections to the Constituent Assembly, the representative body that would write the new constitution.

It was the Maoists who convinced the parliamentary parties to go for the Constituent Assembly, albeit after first acceding to lay down their guns. This was the road to the mainstream, after Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal – ‘Prachanda’ – realised that the Nepali reality, coupled with international geopolitics, would never allow for an armed takeover of the state, as he had long preached underground. And so, Dahal led his flock into the glare of above-ground politics, with the promise of competing in elections and throwing off the old feudal order by the ballot rather than the bullet. This was to be a Nepali example for the world: how a Maoist insurgency could rise above the scorched earth and engage in competitive politics – to fight the good fight for the long term.

But that great experiment is suddenly in jeopardy. It has been difficult all along for Dahal and his comrades to manage the contradiction inherent in giving up armed struggle while misrepresenting affairs to the cadre, so as to maintain unity during the transition. Hardened fighters could not be told that they had lost their comrades in vain, nor could the propaganda about achieving state power through force be jettisoned so easily. At an extended party plenum in early August, Dahal’s relatively moderate leadership was faced with the angry ‘nationalist-radicals’ who charged a sell-out of the revolution. It was around the same time that the Maoists seemed to finally realise that their showing in the Constituent Assembly elections, slated for 22 November, would be abject.

Election panic hit the former rebels, and before long the leadership was digging in its heels – against elections. First, Chairman Dahal proposed that the polls be postponed till April, suggesting that “a revolutionary party never fights an election it cannot win”. Then, the Maoists proposed a 22-point list of demands from the government, as precondition for participating in the elections. Many of these points were, in fact, doable, but for the lethargy of the eight parties in command, including the Maoists themselves. But there were two political demands that were significant sticking points. By putting these points forward, the Maoists were essentially reneging on the agreement signed with the rest of the eight-party coalition. The demand for an immediate establishment of a king-less republic by the interim parliament (and putting a president in place) went against the agreement to let the future of the monarchy be decided by the Constituent Assembly. The other demand was for a ‘full-proportional’ electoral system at the November polls, rather than the mixed system (half of it proportional and the other half through direct candidature) that had been agreed on as a compromise.

Cynical observers had been predicting the collapse of the November elections plans, but not from the direction of the Maoists. Rather, such obstacles were expected to crop up from Nepal’s various agitated communities – the ethnic indigenous groups, the Madhesis of the Tarai plains, the highly discriminated Dalit groups, the Muslims, the high-Himalayan communities, or those of the neglected far west – over the fears of ‘missing out’ on the last chance at full representation. Indeed, the descent into violence of the central Tarai over spring held out a singular challenge to elections. But the Madhesi and indigenous leadership made considered compromises with the government, agreeing to go for the mixed system just to be able to get to the Constituent Assembly, when the people’s representatives would get to work on the people’s interest. And so, despite the challenges along the way, by the end of August the country looked like it was well on the way of holding credible elections.

It was the Maoists, then, who swallowed their embarrassment and decided to try and pull the rug from under the November elections. In fact, it was on the very day that the Election Commission published a code of conduct for the elections that the CPN (Maoist) decided to unveil its anti-election weapon: all Maoist ministers suddenly resigned from the cabinet on 18 September. That same day, at an open rally, the supposedly moderate Maoist leader Baburam Bhattarai ridiculed the ‘sham’ election exercise.

The only saving grace to the debacle was that supremo Dahal was not present at the open meeting, which some thought allowed him the flexibility to go back on the professed radicalism of his comrades. Furthermore, subsequent meetings between the main political players extended the possibility that the Maoists could yet agree to go to the polls, with a compromise formula on the ‘full-proportional’ demand, and the interim parliament agreeing to make a non-binding declaration of intent as far as the republican slogan was concerned. But as the days went on, the continuing harsh words from the Maoist leaders did not inspire confidence in a Maoist change of heart. It seemed that universal international admonition and the appalling loss of face among the citizenry were not enough to goad the leadership to go for what it evidently saw as a humiliating electoral defeat.

Panic attack

The Maoists had clearly suffered an attack of election panic, at the very time that the leadership was being challenged by the hardliners within. As such, the easy way out was chosen: exiting from government and scuttling the elections, without a thought as to what this might do to the party’s long-term journey towards political legitimacy, or how they were holding the national future hostage. But it was clear that by seeking to push back the elections, the Maoists were only postponing the day of reckoning. It was not as if postponement would give them a better chance at the ballot box.

With the Maoists choosing to face an uncertain future rather than immediate humiliation at the elections, the leadership seemed to care little about whether their actions emboldened their supposed arch-enemies, the royal palace and the Nepal Army. The contortions that the Maoist leaders underwent during subsequent interviews and speeches were not amusing to anyone who wished them to rise to the stature of true politicians. Here was a party in a hurry – unwilling to train its cadre to engage in open, competitive politics; willing to blackmail its way to a postponement of elections. It seemed uncaring of the fact that the country was rife with scores of mutinies, with more being born by the week, all of which would be encouraged by the Maoists’ opportunistic diversion.

In the end, unable to tackle the contradictions within the rank and file, and challenged by the radicals who themselves could show no viable long-term plan, Dahal seemed to have decided to jettison the haughty image of a party that spoke for the masses, and force an election postponement by hook or by crook. And there, the Maoists had it easy. They could stall the election preparations simply by folding their hands and refusing to move, knowing full well that, because the Constituent Assembly elections and the half-complete peace process go hand-in-hand, the polls could not be held without their participation.

For all that has been invested – and all that has succeeded – in the peace process thus far, it will not be realistic to go through the elections without the Maoists. To begin with, they retain the ability to cause mayhem, albeit without the people’s support. Some do point out that Nepal is already far ahead compared to other countries where armed insurgencies are being brought into open politics, and that a few months of postponement will not necessarily be catastrophic. The only problem with such an argument is that the Maoists do not seem to have a plan in place in the event of postponement. Certainly there is no agenda to return to the jungle. But what if the party’s energy dissipates even further during the interim period? What if the many pressures lead to a splintering of the CPN (Maoist), a fate that the people have been saved from thus far. In the instability that the party seems to want to construct, an unrepentant army would be emboldened to emerge from its barracks, and the international community might feel compelled to back an interim army-backed political arrangement. Even as late as the end of September, the desperate hope was that the Maoists were playing at brinkmanship, and that they would pull back from the ledge – and join the November elections.

There seemed to be an incongruous convergence at play in Nepal: between the conservatives within the Nepali Congress party, who do not want an election just yet; the Maoist radicals, who have dragged the entire leadership into an anti-election stance and the people be damned; and the royalist-militarists, the criminal elements in the Tarai, and the many opportunists in every agitated community, who want to ensure that no election takes place and to take advantage of the ensuing instability. Not that there is a grand conspiracy afoot among any of these forces, however. It is only the CPN (Maoist) that at this date has the ability to scuttle the polls.

Koirala’s government

It is not that the other political leadership is blameless in the situation facing Nepal at the end of September 2007. Indeed, all eight parties in government can take the rap for sluggish movement on the matters for resolution mentioned in the Comprehensive Peace Accord. While critics of the Maoists would point to their unleashing of Young Communist League hooligans upon the populace, there has not been enough of an appreciation of how disciplined the fighters sequestered in the cantonments have been under abysmal living conditions. Likewise, when angry analysts accuse the government of sometimes appeasing the Maoists, there is not enough sympathy for the contradictions the leadership is having to tackle, or for the fact that the Maoists have indeed given up the gun. The distance that the Maoists have travelled, and the impossibility of their going back to the jungle as the united force of the past, should give pause to those who would attempt to corner the Maoists without any hope of exit.

Much of what constitute the Maoist demands as included in the 22-point roster rest on the reality of government inertia and myopia. There has been delay in appointing a Commission on the Disappeared, in providing minimal support for the families of the more than 13,000 killed during the course of the ‘people’s war’, and in providing for the future of the Maoist fighters currently in seven main cantonments. These failures of the government which Koirala heads have clearly been contributory to the Maoists’ decision to quit government. While the ensuing days have indicated that the Maoists were looking to use every argument available to them to opt out of the elections, the government could have done much better.

Girija Prasad Koirala’s personalised, centralised style of governance, coupled with the lack of institutional memory in a (non-existent) prime minister’s office, has grievously hurt governance in general over the past year. Against dire institutional and personal (including health) pressures, Prime Minister Koirala seems bent on trying to do things himself, even as government flounders for lack of attention. To begin with, practically from his sick room, the prime minister has had to oversee a unification of his rump party, the Nepali Congress, with the breakaway faction of Sher Bahadur Deuba. As head of state and head of government, all of the ceremonials – from diplomatic to cultural-religious – that used to be the king’s monopoly are now on his octogenarian shoulders. The absence of motivation up and down the ranks of state bureaucracy and police administration must ultimately be blamed on Koirala.

Meanwhile, the prime minister has kept intact the army, whose accountable officers have not been penalised for having carried out a dirty war, nor for having backed the coup conducted by Gyanendra in February 2005. It is clear that Koirala has made a conscious comprise to leave the Nepal Army alone, keeping in mind a possible Maoist misadventure. But what he has done in the process is made the Maoists jittery, even while making it difficult for what is known as ‘security-sector reform’ to be carried out. This process is required to give confidence to the Maoist leaders as they demobilise their fighters, and to recognise their ‘sacrifice’ for having decided to come up to open politics.

There is no doubt that an army that was allowed to quadruple in size in the last few years in response to the Maoist challenge, to about 100,000 today, must now be downsized to at least its original girth, even as debate is begun on the country’s real military requirements. Reform of the security sector would also address the training and use of the Armed Police, which is evolving as a blunderbuss weapon of state. It would also have to address the utter lack of motivation among the civil Nepal Police, which has the primary responsibility of maintaining law and order, including in the face of elections.

As far as the peace process is concerned, however, the most important element in reforming the security sector is arranging for the future of the Maoist fighters residing in the cantonments – who represent a powder-keg that has not been given due consideration by the political class and civil society alike. True, the Maoists kept many of their fighters out of the UN-managed cantonments, and created instead the violence-prone Young Communist League; it is also correct that the Maoists have inducted many boys and girls into the cantonments to inflate their numbers (more than 30,000) of their fighting force. The informal understanding among the concerned parties is that, after a verification exercise is completed by the United Nations, about 15,000 fighters will have to be rehabilitated.

A formula must be devised to provide education, skills training and ‘golden handshakes’ to a good number of fighters, who would then return to civilian life. However, it will be important to ingest a portion of the ‘People’s Liberation Army’, even if they are the indoctrinated fighting force of a political party, into the country’s security services as part of specially created units or of the regular units, under negotiated criteria. This must be done for the sake of peace, a pound of flesh that will have to be made over to the Maoists. The resistance of the Nepal Army, in particular, will have to be overcome.

The election dividend

It is due to their understanding and resilience, together with the firm hope that tomorrow will bring a better dawn, that the Nepali people have shown patience with an essentially non-existent government. Months of having to stand in line for a trickle of gasoline have frustrated the middle classes. In the plains, exceptional floods have come and gone without the government rising from its slumber. The peace dividend has not appeared, and a year and a half after Gyanendra’s autocracy was brought down and the Maoist armed revolt ended, the people await human rehabilitation and restoration of infrastructure. The ‘donor agencies’ will not give money in any significant quantity to a government that does not have the requisite disbursement capacity, and so development activities have not been revived . The violence in the Tarai, the endless bandhs and closures, have kept the economy from taking up expected momentum over the last year. In addition to all of this, the people have suffered through a period of escalating communal tensions, a heart-stopping evolution that could only have happened when the state was this weakened.

At a time when the citizenry has set its collective heart on the Constituent Assembly deliberations as the way to lift the society out of the morass and to build the future that beckons, the Maoists have without so much as an apology turned the process on its head. Society at large, as well as the political parties, is now required to make a calibrated surrender to the Maoist blackmail: the elections will not happen if Dahal says he will not budge. At which point there will be no way forward but to reschedule the polls. In the meantime, in the event of such a scenario unfolding, it will be important to use the interim to do all the things that were already desperately needed.

First, it is important society to insist with one voice that the eight parties, including the CPN (Maoist), remain together as an alliance that backs the government till the elections. Given that there is no other alternative at hand, and even though the credibility of such a combine has taken a beating, the legitimacy for creating a government remains with the eight parties more than with anyone else. Second, polls can only be postponed on the condition that they will be held at the first possible date thereafter, over mid-winter or in April. Third, during the interim it is crucial that Prime Minister Koirala rise from his sick bed and semi-seclusion – to inject energy into the government, do what is required, most importantly in reviving rule of law across the land. Having succeeded in uniting his fractured Nepali Congress party during the last week of September, Koirala should now rise above the position of a political party boss and reach for statesmanship: to feel the pain of a confused populace, and give the citizenry which was capable of conducting something as glorious as the People’s Movement the quality of government it deserves. The prime minister must also ensure that his work be guided by a sensitivity to identity-led demands, and understand how they represent very deep-rooted resentments with the state establishment. Fourth, on the rehabilitation and development front, the people will lose heart if the country is forced again to wait much longer for elections while everything else is kept pending. A well-funded authority must be established with a two- or three-year mandate, to amass USD 2-3 billion internationally and spend it effectively in rehabilitation and rebuilding exercises – in a way such that the government of Nepal can take all the credit.

The Maoists’ period above ground has been invested in trying to keep the party together through loud talk and misrepresentation – proposing that the CPN (Maoist) has won when in fact in a grand compromise it had given up its central element, the armed revolt. The past year and a half was squandered by the former rebels, who did not even use their five months in government to highlight social issues that have been part of their worldview, which would have appealed to the underclass and could have offered the party increased confidence to go to the polls. Instead of setting the agenda, the Maoist leaders have evolved from fighters to those who whine at all and sundry – and, ultimately, they are acting as spoilsports.

While giving them the credit for understanding when the ‘people’s war’ was no longer a viable proposition, the Maoists should have taken it upon themselves to push the transformative agenda, and moved to educate and socialise the cadre for open politics. As such, there is no way out for the CPN (Maoist) but to gird up its courage and go in for the Constituent Assembly elections – if not in November, then at the most practical date thereafter. There is no shame in doing poorly in an election exercise if your agenda for social transformation is meant for the long term, as it perforce should.

The romance of the revolutionary emerging from the shadows into the limelight is over, even for Kathmandu’s enchanted literati. What remains is the image of a party without political staying power: one that, in a bout of election fright, has jeopardised its own future for the sake of the momentary warmth of the bed-wetter’s mattress (mootko nyano – an acceptable Nepali expression). The invincible, all-powerful image of the revolutionary party has taken a beating. Nobody would have wished it this way for a party that should have emerged – and may it still – as the political representative of the underclass, in a country full of underclasses.