From Nepali Times, ISSUE #751 (27 March 2015 –2 APRIL 2015)

Prof Theodore Riccardi presents historical material to enrich our lives.

Nepal has evolved, sadly, as a country where history and archaeology are far down in everyone’s priority. Throughout his career, the Indologist and pioneer Himalayanist Theodore Riccardi has sought to highlight aspects of Nepal’s past in the expectation that his excitement will be catching.

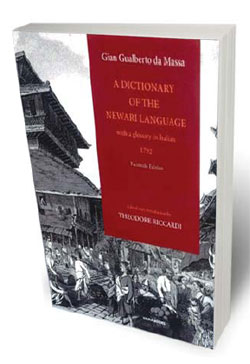

Riccardi’s latest offering is The Dictionary of the Newari Language, published by Vajra Books, which was inaugurated and commented upon by the linguist Tej Ratna Kansakar on Sunday. The dictionary was prepared in 1792 by Capuchin monks even as they were thrown out of the Valley by the invading Gorkhalis, and the text ended up at the Vatican archives in Rome. Riccardi spent considerable energy extracting the text from the papal administration, to present us this beautifully crafted volume.

As Riccardi’s spouse Ellen Coon stated at the launch ceremony, his career has been devoted to generating students rather than publishing tomes. He has been guru to an entire brigade of scholars on Nepal and the Himalaya, including Bruce Owens, Todd Lewis, Bill Fisher, Lynn Bennet and Gabriel Campbell. The contemporaries whose life and work has been enriched by Prof. Riccardi include Prayag Raj Sharma, Mohan Khanal, Ramesh Dhungel and Nirmal Man Tuladhar.

Conversation with Riccardi sparkles with names of the constellation of personages who have added scholarly texture to the study of Nepal: A.W. Macdonald, Harka Gurung, Khem and Dor Bahadur Bista, Fuhrer von Hamiendorf, Fr. Marshal Moran, L.S. Baral, Kamal Prakash Malla, Lain Singh Bangdel and David Snellgrove.

With glossary in Italian 1792

By Gian Gualberto da Massa

Facsimile Edition

Edited with Translation by Theodore Riccardi

Vajra Books, Kathmandu 2015

Rs 25,000

The first challenge for this Philadelphia boy who arrived in Kathmandu in October 1965 via SOAS in London as a student of the Nepali language, was to decipher the distinction between ‘haina kyarey’ and ‘haina byaray’ (approximate translation by writer: ‘no that’s probably not true’ vs. ‘you don’t say!’) Even at the book launch, while having a bit of a difficulty due to the Parkinsons affliction, Riccardi was indulgently admonishing one acolyte given to profuse admiration: ‘Haina byaray!’

Riccardi is an excitable humanist and polymath. He teamed up with Khanal to excavate a sixth century site below Changu Narayan. He was a founding editor of Kailash, co-edited the Himalayan Research Bulletin (now Himalaya, The Journal of Nepal and Himalayan Studies) with Owens and Fisher, and together with Lewis and others, prepared a syllabus and bibliography on Himalayan Studies (now digitally available).

Riccardi has written about the Manadev inscription at Changu Narayan and picked up ancient writings being sold as food wrapping in the Asan market. There is a bronze statue of our social democrat statesman BP Koirala, made by a Bulgarian sculptor, that Riccardi rescued from the dumpster. Today, the statue stands at the corner of a quiet field in the backwoods of Virginia, safe for the time when the world wakes up to take custody.

It is time Nepal woke up to organise the return of religious iconography stolen from our living culture that today adorns the museums and private collections of the West. Riccardi was in Kathmandu when the looting was gaining momentum in the 1970s, and watched livid from the sidelines as the idols departed, with the complicity of a line of thugs from the local goonda to Panchayat power-brokers, ‘Asian art historians’, aid workers, plenipotentiaries with access to diplomatic courier bags, and private collectors and museum executives overseas. His fictional account of the idol theft industry in Himal Southasian magazine provides grist for when we wake up to demand a return of the stolen pieces in their thousands to Nepal and to the original sites.

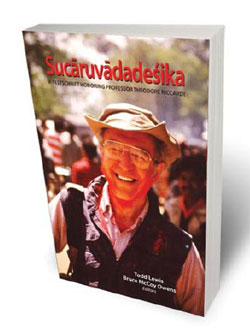

In 2014, his students and admirers came out with a ‘festschrift’ honouring Riccardi, titled Sucaruvadadesika, which could be translated as ‘the beloved teacher whose speech is delightful’.

The contributions to the volume (Himal Books) themselves indicate the breadth of scholarship and thinking that this ‘citizen of the Himalaya’ has triggered in the course of his academic journey, so vibrant, wide-ranging and empathetic.

Due to the push and pull of today’s ultra-populist discourse, Kathmandu’s intelligentsia is undergoing a bout of historical denial, hopefully temporary. When we are ready to take on our history, Riccardi’s output will help us to use the existing but neglected material to – in his own words – “create the Nepali past”.

This is also how we must accept the gift of The Dictionary of the Newari Language, with the terms in Prachalit script and the meaning given in Italian, of Newa Bhae in its ‘original’ form. Like so much else that Riccardi has gifted Nepali society, this is his ‘naaso’, to hold in trust till such time that we are ready to acknowledge, appreciate and utilise.