From HIMAL, Volume 7, Issue 2 (MAR/APR 1994)

The camera cheats on the Himalaya because the filmmaker gets away with it.Documentaries will become more truthful as the locals get to critique them.

On 22 July 1993, in the village of Ghemi in Upper Mustang, crew members of a company named Intrepid Films was shooting a documentary for the US-based Discovery Channel. The film was to be on the cultural and natural wonders of Mustang, the principality that was opened to tourists in early 1992. Tony Miller, the director, —who also held the camera — was on the lookout for anything that would make his film stand out.

To provide a storyline for his narrative, Miller had brought along Rinpoche Khamtrul, a lama from Dharamsala whom he had met in Kathmandu. The camera would follow the Rinpoche’s travel together with two assistant monks up to the walled enclave of Lo Manthang, the capital of Upper Mustang.

It was late evening. At the house-cum-hotel of Raju Bista, Ghemi’s aristocrat, Miller was filming one of the monks brushing his teeth. From behind the camera, Miller was asking questions relating to local hygiene and the omnipresence of lice in Mustang. The young lama was providing earnest answers to the questions.

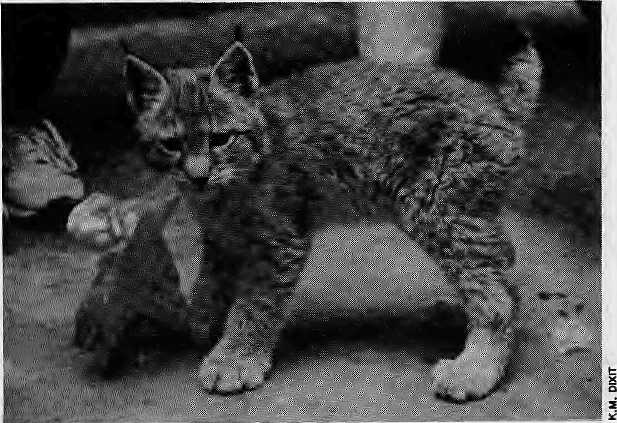

It so happened that a baby lynx (Lynx lynx) had been found by the residents of Lo Manthang and was being transported down to the national zoo in Kathmandu. The animal, too, was spending the night under Bista’s roof, together with its handler.

Not one to miss the chance of incorporating this elusive, endangered animal into his film, Miller swung into action. He got permission from the handler, a worker from the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP), to expose some footage. A yarn was concocted within minutes and incorporated into the script.

As the evening enfolded, the lynx sequence was acted out under the arc lights and reflectors. An assistant lama goes up to Rinpoche Khamtrul, produces the animal, and announces that it has just been found in the hillsides of Ghemi. With Miller prompting him from behind the camera, the Rinpoche takes the lynx (“Ikh” to Loba) into his arms and sighs, approximately in these words, “Ah, these animals used to be abundant around these parts. Now they are no more.”

The baby lynx is willing to play its part, and as if on cue begins to frolic with the lama’s rosary, making snatches at it with its padded paws. No director could wish for better footage, and Miller is ecstatic.

Faking It

Unless it is a docudrama or carries an appropriate disclaimer, a documentary is not supposed to fictionalise. Additionally, even when he is not presenting fiction, there is a burden on the documentarist that his camera be as candid as possible. Due to the moving picture’s power of manipulation — much more than still pictures or print media — the cinematographer has a larger responsibility to respect authenticity. The audience accepts documentary films on faith.

That, of course, is the theory of it. All film enthusiasts know that cent-percent candidness, while it might be within reach in still photography, is practically impossible in cinematography except when you have a hidden camera, which has its own problem with ethics. Because of the nature of the visual medium and due to demands of equipment and large crews, documentary filmmakers invariably find it necessary to stage sequences — one cannot just point-and-shoot a documentary. Besides camerawork, in the process of scripting and editing as well, there are numerous opportunities for sleight of hand.

For the very reason that it is so necessary to set up scenes, it is important for the documentarist to know and respect the limits and not to play too fast and loose with the facts he claims to present. Under normal circumstances, these limits are defined by the critics’ and the audiences knowledge of the subject and of filmmaking. If he is not careful, the filmmaker loses credibility.

Thus, the viewer’s potential rejection is the built-in safeguard which keeps the filmmaker on line. But when the subject of the film is a remote pocket in the Himalaya, both the target audience (in the West) and critics are at the mercy of the director or producer.

The temptation to take short cuts and to stage sequences beyond the bounds of propriety are in place for film companies that arrive in the Himalayan region. The Western audience is taken on a celluloid ride — often willingly, it seems.

Lynx Sequence

There were several problems evident in Tony Miller’s approach to filmmaking, at least at Ghemi. If his film were to be certified a genuine ‘documentary’, Rinpoche Khamtrul should already have been on a trip to Lo Manthang when the film crew stumbles upon him. If not, then at the very least the lama should have made an earlier trip to Lo Manthang, in which case at worst the director could be accused of re-enactment. Instead, Miller has simply gone and chartered himself a rinpoche.

Now, when Miller completes editing the film, the only ethical way out for him is to include a notice stating that the Rinpoche’s trip was staged, but that the rest of Mustang— the gumbas, the potato fields, the Kali Gandaki canyons — are for real.

Not only does Miller bring along Rinpoche Khamtrul to Mustang, he has the venerable lama mouth untruths. Apparently, Rinpoche Khamtrul had not visited Mustang before this. A refugee from Kham living in Dharamsala, he could not be an expert on the status of Upper Mustang’s wildlife. Neither the Rinpoche nor his prompter, Miller, are in a position to know whether the lynx as a species is abundant or scarce in the vicinity of Ghemi. The valley upriver is a high sanctuary which could well support a substantial population of lynx. The first wildlife inventory of Upper Mustang was being conducted by an ACAP team in July even as Miller was filming.

Sky Burial

Mustang seems to attract documentarists who exel at faking it, even though this is one region that does not need to be made to look more romantic than it already is. The last two years has seen Mustang attracting more than its fair share of filmmakers. In fact, Rajasaheb Jigme Parbal Bista has had his hands full dealing with emerging class conflict, much of it sowed by free-spending, insensitive film crews, including Intrepid’s.

A team from the Japanese television station NHK managed to be the first to film Mustang when it was opened. Their production, while containing some good camerawork, generates snorts of disbelief among Loba who have seen video copies. It is a subject of much derision among the patrons who gather for chhang and tea at the popular bhatti of the “Hema Malini” of Lo Manthang.

The NHK director’s interest is to heighten the sense of drama. He is out to out-Piessel the adventurer-author Michel Piessel (the writer of the original mass-market book on Mustang). The film begins by implying that the crew is driving almost all the way up to roadless Mustang in two properly Japanese four-wheel-drives. It then hypes up a helicopter rescue of a team member who gets altitude sickness at an embarassingly low altitude.

As the camera progresses northward, the routine police check of trekking permits is presented with ominous music and tense close-ups. A palpable sense of relief is conveyed when the hawaldar flips through the permit and sternly waves the team along. The impression is that the Japanese film crew might otherwise have been thrown into a dungeon holding a hungry Tibetan mastiff, or given sky burial.

Lo Manthang, when the NHK camera finally arrives, is dolled up to look like a garrison town under seige by Khampa marauders. For a settlement where the Rongba (midhill) police know to keep a low profile, there are policemen standing guard on every rooftop, bolt-action rifles on the ready. Sleepy and docile Lo Manthang is presented as a Dangerous Place, one from which the NHK team emerged alive to tell the tale.

Cinematic Quacks

More than one documentary shown at Film Himalaya 1994 engaged in sleight of hand, secure in the knowledge that the Western audience for whom these films are made would not notice. Otherwise, why should good old samaritan Dr. Ebehard Brunier, a dentist from the German town of Mainz, come to Mustang to pull out teeth? The answer is simple: he did it for the television camera. Dr. Brunier’s narration in The Dentist from Mainz is child-like, and the public health aspects of his exercise questionable. For someone out to do good, Herr Doktor seems to travel without a dentist’s drill, which reduces him to pulling out more teeth than he probably should have.

The problem of candidness, again, is what looms large in a film like Dentist, which utilises the Himalayan backdrop merely as a prop for a self-aggrandizing exercise. Every time we see Dr. Brunier walking alone through the hills of Nepal, tousling children’s hair and distributing plastic mouth-rinse cups, we know that behind the camera are arrayed the cameraman, producer, director (Hermann Feicht), soundman, gofer, sirdar, porters, yaks and donkeys. The viewer, however, is likely to believe that this is the story of a lone dentist and his trusty donkey heading up to Mustang to do good. Another pitfall of ego-driven films: you stage more scenes to create proper atmosphere, almost as if you were shooting a feature film.

At the end of Dentist, the German public television company ZDF announces that it is providing U$ 10,000 for a clinic which Dr. Brunier is going to establish in Lo Manthang, as promised to the Rajasaheb. That was more than a year ago. Apparently, no Loba has heard from Dr. Brunier in the interim. In addition, Nepal’s Minister for Tourism and Civil Aviation Rain Hari Joshy is said to have waived Mustang’s hefty entry fee for Dr. Brunier on the promise that he would pay NRs 50,000 towards a school building in Lo Manthang. The money has yet to be collected.

Meanwhile, there is much hilarity in Hema Malini’s bhatti as the patrons recall the dentist who set up a stool by the town gates and pulled out the wrong tooth of so-and-so. But it is the dentist from Mainz who had the last laugh.

False Galahad

Galahad of Everest, a film that has garnered much praise in mountain film festivals elsewhere, must be seen for its misplaced hubris and cinematic arrogance. British actor Brian Blessed tries to recreate George Leigh Mallory’s 1924 trip to Chomolongma’s North Face. In addition to numerous staged sequences, the film has several faked ones as well.

As Mallory, Blessed is supposed to be heading north into Tibet from Darjeeling. Instead, he pops up in the vicinity of Bhutan’s Takstang Monastery. Next, Blessed crosses over the photogenic bridge at Paro Dzong, and — as the film editor would have it — drops in on the Dalai Lama. Once his meeting with Dalai Lama is over (most likely 600 miles over to the west in Dharamsala), Blessed is again out on a Thimphu street, bantering with a provision store owner.

The chutzpa with which Blessed carries out this deception would be comical, if the sequence did not make clear how little he cares for facts and sensibilities. The scene of the Dalai Lama comfortably ensconced in Paro Dzong, for all the unease that exists between the Tibetan government-in-exile and the Thimphu regime, has implications which Blessed is bothered with. For him, the Dalai Lama is a prop, whose amenable presence on the screen, incidentally, is also used by other opportunistic makers of documentaries.

In Search of the Buddha, by director Paulo Brunato, is insufferable enough for the Buddhist discourse by Hollywood actors. There are reports that this film, which speaks of the loftiest of principles, was not above deceit. At one point, the camera visits a Western ascetic meditating outside his flood-lit cave entrance somewhere in the hills of Kathmandu Valley. Word has it that the ‘cave’ was actually a hole dug for the purpose of filming. There are said to be other made-up sequences as well in Buddha.

Hit-and-Run

Numerous documentaries in ‘different genres screened at the festival stayed within the ethical limits while presenting fine stories and visuals. It is the filmmakers who are careful of the ethnological perspective that tended to produce the most sensitive and illuminating films. Conversely, the most dishonest documentaries were by producers and directors affiliated to television channels, whether public or private. These hit-and-run documentarists have little emotional attachment for their subject, and their treatment suffers. There is no embarrassment to taking short cuts if you know that after Mustang your next assignment is the Shetland Islands.

So, why does the filmmaker cheat? The answer might be that they do not care enough for the locals and their sensitivities; the target audience is in the West (or in Japan) and does not know enough to catch the filmmaker out; the subject community does not get a chance to see the film and react ‘effectively.

The temptation to fake increases proportionally with the distance between the audience and the subject peoples.

Meanwhile, if it is the responsibility of the film critic to keep cinematographers on the straight and narrow, it fails to work when it comes to Himalayan films, which are aired primarily on Western networks and public television. Since the critics do not have the background to comment on the content of films on complicated Third World topics and locales, their critiques rarely go beyond the superficial. Like the general audience, the film reviewers, too, tend to get carried away by the grandeur of mountain vistas and the romance of Himalayan communities as presented by directors.

Even the most respected specialised forum of the Margaret Mead Film Festival, whose focus is on anthropological works, often showcases poorly made films on the Himalaya, to much applause. The discerning local audience would hoot down many of the films that receive wide-eyed appreciation at Western film festivals.

The camera cheats on the Himalaya because, thus far, the filmmaker has been able to get away with it. One way to promote documentaries that stay closer to actuality is to ensure that more subject audiences get to view them — in films festivals, national television, and via cable and satellite—and to react. Next, it is for the locals to develop the capability to produce documentary films for the Himalayan audience. The third step is for local filmmakers to acquire the sophistication necessary to present their region on film to the Western mass audience.

But at that point, might we find that local filmmakers are just as prone to taking short cuts?